THE PHOENIX GENERATION

(Vol. 12, A Chronicle of Ancient Sunlight)

|

|

| First edition, Macdonald, 1965 | |

First published Macdonald, October 1965 (25/-)

HW’s diary entry for 28 October 1965 notes: ‘The Phoenix Generation published today — (The Pathway was pub. 28/10/1928).’

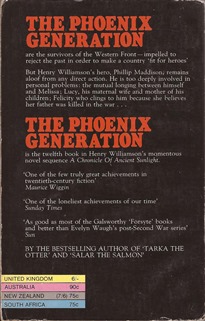

Panther, paperback, 1967

Macdonald, reprint, 1985

Sutton Publishing, paperback, 1999

Currently available at Faber Finds

Epigraph, on title page:

'Thou knowst how drie a Cinder this worlde is

That ‘tis in vain to dew or mollifie

It with thy tears, or sweat, or blood'

John Donne

There is no dedication.

HW’s title here is powerful and quite explicit: the phoenix is a mythical bird of the Arabian Desert that after living many centuries (normally 1000 years, thus constituting a millennium) immolates itself on a self-built funeral pyre, only to rise again from the ashes with renewed youth to live through another cycle.

For HW ‘the phoenix generation’ is those who survived the funeral pyre of the 1914–18 Great War and whose duty it is to rise again from its ashes and (from HW’s viewpoint) prevent it ever happening again: to make a new and better world – a Utopia (the irony being that such a place does not and cannot exist: the Greek derivation being a play on words meaning both ‘a good place’ and ‘no place’). The source is the book of that title by Thomas More (1477–1535), published in 1516. Its full title translates as: ‘A truly golden little book, no less beneficial than entertaining, about the best state of a commonwealth and the new island of Utopia’. On this happy island all things are held in common, gold is despised, and people live communally. More reflects that he would like to see this state implemented in Europe; but doubts they will be. But one can see the connection with HW’s own thinking, especially here in this volume.

HW’s title page quotation reflects and underlines the intensity of his concept. John Donne (1572–1631) is considered a (indeed the) metaphysical poet, but probably for HW meeting rather more the parameters of the Romantic genre, of which HW was the modern counterpart (an eminent critic called him ‘the last Romantic’). The title of the poem quoted here is: ‘The First Anniversary, an anatomie of the World. Wherein . . . the frailtie and the decay of this whole World is represented’.

(The background to this quotation is fully discussed in Anne Williamson, ‘Rise and Shine Again (As a Phoenix Regenerated)’, HWSJ 48, September 2012, pp.36-62: the article was written in riposte to Michael Coultas, ‘Decline & Fall, Part II: Ashes of the Phoenix’, HWSJ 47, September 2011, pp 62-75)

The Phoenix Generation, covering the period between 1929 and 1939, is to be, then, an anatomy, a distillation, of the world as it appeared to its author in the period leading up to the Second World War.

************************

We have to pick up at the situation that HW found himself in at the end of 1962, when he had finished writing volume 11 of A Chronicle of Ancient Sunlight, The Power of the Dead, planning to immediately start work at the beginning of 1963 on No. 12, this volume, The Phoenix Generation. The shock of his wife’s desertion just before Christmas 1962 (exacerbated by the fact that the man she left him for was the son of Second Lieutenant George Fursdon, his platoon officer during those terrifying months in the trenches with the London Rifle Brigade over the winter of 1914-15, just about 50 years previously) threw not only his personal life into disarray: it also greatly affected his writing schedule. He wrote into the front of his 1963 diary:

A moment of heavy despair which is borne somehow. It is hard to realise, to accept, the fact that my wife has left me for ever and for ever. She is part of my life – the best part, the major part: I would say, the only part.

His diary for 3 January 1963 records:

Am taking barbitone by day – it keeps me level-feeling – and 2 small sleeping pills at 11 pm. But one aches with loss. Cannot think about how to begin No. 12, as I had planned to start about now.

He then, accompanied by Harry, his son by Christine, made a visit (by train; he had been told not to drive) to Bungay in Suffolk to stay for a few days with his first wife Loetitia and their son Richard, but recording again on 9 January:

I cannot write, or begin, No. 12 as I had hoped, before the shock, on New Year’s Day.

On 17 January he noted the death by suicide of Sylvia Plath, the wife of the poet Ted Hughes: ‘. . . his grief was my grief & I wrote to him.’

Despite this constant emotional turmoil he was writing articles for The Sunday Times for their 'Out of Doors' series: these can be found in From a Country Hilltop, ed. John Gregory (HWS, 1988; e-book 2013). There were 15 titles written between January 1962 and the end of October 1964. But it was a very bad time.

On Sunday 24 March he recorded: ‘Perhaps shall be able to write again soon.’ The next day he took the train to London (where he was depressed), and then on to Beccles, and so to Bungay. On his return to London he attended the Memorial Service for General Sir Hubert Gough – ‘most moving’. Gough had been Commander of the Vth Army, with its emblem of the red fox, all of which meant so much to HW. (See A Fox Under My Cloak, Vol. 5, A Chronicle of Ancient Sunlight)

9 April: Battle of Arras, 46 years ago! [HW was then in the thick of it as Transport Officer with 208 Machine Gun Company at the Front just south of Arras.]

Then on 19 April he recorded:

Went to field & did some work on chapter I of The Phoenix Generation (No. 12).

20 April: ‘I wrote some more of No. 12’

The following day his son Richard arrived at the field for a visit: HW immediately whisked him off to see Bryony Duncan and friends, and then on to Rosemarie Duncan at the Wellcombe farm (the daughter and wife respectively of the poet Ronald Duncan).

Tuesday, 23 April: To field, where I wrote chapter 2. . . . [Richard was staying in the caravan at the field, also writing.] Wrote 2000 words, some embodied from cut pages of revised edition of Children of Shallowford put out last year or year before. [This was the revised edition of 1959 – see the page for The Children of Shallowford, where this use is shown.]

HW was hoping Richard would ‘take charge’ of the chaos Christine had left, but this was impossible: Richard had to return to Bungay by 1 May. Richard’s brother John arrived briefly at the weekend with the Countryman van HW had given him previously, and helped move furniture. Harry also came for a few days over his Easter break. HW also noted that he had written to Ruth Tomalin to ask her to come and help but had had no answer. Ruth too had her own life to lead.

On 5 May, having had an altercation with Christine, who had changed the arrangements over return of Harry, HW was in considerable emotional turmoil:

What will be the end of this tragedy? I must write: but also plant the garden. The old dilemma: plus housekeeping, etc.

[Underneath in red ink] I wrote Chapter 4 of 12 – the hunt ball scene – until 7.50 pm in the hut.

He was now trying to sort out facts for the divorce case for his solicitors and obtaining statements for evidence about both Christine’s affaire with John Fursdon, and her earlier affaire with Allan Bowyer (an artist who lived in Appledore): he was determined ‘not to be divorced for a fake adultery’. But the writing was now resumed.

8 May: Writing in field – Chapter 3 – or will it be 4. Phillip is about to leave for the U.S.A.

11 May: To field as usual about 11 am. . . . Phillip is now in Florida – by way of a free ticket from The Linhay on the Downs. [I am not totally clear what he means by that.]

13 May: In field. Finished chapter 4. Have I been rather cunning? For Felicity is woven emotionally into the articles (ex Sunday Sentinel, otherwise Referee, where these 1934 (changed to 1930) articles originally appeared at £2/2/- each & later in Linhay. Ph. sends them to Felicity at home (enceinte) who types them & muses on his life there. Thus we get a flowing portrait of Felicity.

(The USA passages in The Phoenix Generation were removed at a later stage, actually on my advice, as it was an easy way to cut the book back to the length required by the publisher.)

On 17 May, very worried about the safety of material stored in the hut and studio, he recorded: ‘Packed up about 22 bundles of Tss & Mss including Tarka & Salar for presentation to Exeter University tomorrow. Wrote No. 12. Used some of AT’s letters for Felicity.’

He took the manuscripts to Exeter the next day: almost exactly two years ahead of the actual official presentation in May 1965. Work on No. 12 continued sporadically between bouts of depression and despair. On 30 May he was cheered by ‘A beautiful ariel letter from Margot in Natal. The “Melissa” of my novel.’ (Margot Renshaw, daughter of Sir Stephen Renshaw, was originally from Instow but married at end of the Second World War and left to live in South Africa. The Renshaws are connected to the Chichesters and Hibberts through marriage – and so are cousins of HW’s first wife Loetitia (née Hibbert).

31 May: I wrote some of the chapter 5, Piers & Phillip walking over battlefields in 1930 – lifted from The Wet Flanders Plain, as part of the book went into Power of the Dead.

3 June: I came to a standstill over the novel. I forget what has already been written: and am copying bits of Wet Flanders Plain: the (now) walk of Phillip & Piers. [But my thoughts about Christine] are spoiling the novel.

(These thoughts were chiefly related to the complications of the legal side of the divorce – Christine was constantly havering about her plea, as Fursdon was apprehensive about what any scandal would do to his family reputation.)

20 June: Posted pp. 1-31 of No. 12 to E.M. Tippett. Arranged to see C. on mid-summer day [did not happen].

24 June: pp. 32-117, Chapter 2 & 3 posted to E.M. Tippett.

25 June: pp. 118-188 sent – chapter 4 & 5

I altered – cut – removed – the foolish climax with Melissa today, & made Phillip sail over the bar in his new dinghy Scylla, get into rough water, & return, calm because of Barley. This realised late tonight was false. In the original scene (in my life 1931) it was the presence of Margot Renshaw, then 16½ years, that gave me confidence & equal-mindedness in the storm, No. 7 wind, and we sailed across to Crow Island & back.

Work on the book now stopped. At the end of June HW went to visit Sir Richard and Lady Lucy Dynevor at Dynevor Castle, Llandeilo, Wales, also noting that he visited ‘Bill Kidd’ ‘in his lonely house under Black Mountains . . . Found he’d not been into town for 2 years. Yellow, grey, still same old Bill. Mother, like him, aged 98, lives with himself & his wife.’ So here is the genesis for Piston and his mother who appear in the final novel of the Chronicle, The Gale of the World.

On 4 July proofs for The Power of the Dead arrived – ‘I got happily into them’ – which kept him occupied for over two weeks altogether. At the end of July his son Robert visited and Elizabeth Tippett, who typed his manuscripts, who was to stay in the field while HW went to stay with John Heygate in Ireland with his daughter Sarah and son Harry. The young people apparently enjoyed the holiday – but it was not totally successful from HW’s point of view, as he quarrelled with Heygate, who sent him packing, and he had to travel around for a few days before he could get passage home.

At this time he was visiting the Duncans frequently (Ronald Duncan, poet and entrepreneur of Devon Arts Festivals, who collaborated with Benjamin Britten on Lucretia). On 30 August they visited him at the Field bringing with them ‘the half Swedish beauty Kerstin (she is ½ Chinese)’. Kerstin was recovering from an affaire (HW gradually deduced that this was with the MP Ian Gilmour) and was consequently extremely unhappy. They all went back to the Ilfracombe cottage where HW had prepared soup and crab salad, wine, apple tart and cream. HW fell for this intense and unhappy female.

In early September he was involved in filming on Exmoor and the surrounding area for the BBC, under direction of John and Ann Irving: ‘filmed in Oare Valley, & Hoar Oak – on a hillside – NOT the Hoar Oak I saw with S.P.B. Mais in 1923 when we walked from Blackmoor Gate to Challacombe, up by Pinkery Pond & over to Oare & so to Lynton, where we entrained back to Blackmoor Gate & on the Norton back to Barnstaple.’

Then on 22 September he left with Ronald and RoseMarie Duncan and daughter Bryony for what turned out to be a marathon holiday in Italy. HW was too exhausted and upset to enjoy the travelling and the Duncans often left him to himself – for example, in Rome they dined with Ezra Pound at least twice, excluding HW. On their return to England on 7 October HW went in immediate pursuit of Kerstin, trying to persuade her to come and live with him in Devon. On 15 October he recorded:

Cannot see space clear ahead to resume work on No. 11 [he means 12] broken off god knows how many weeks back.

17 October: [Plymouth] Met Julia Cave, my 28-year-old producer for a BBC TV 1914–18 programme – 26 half-hours for 1964, I to appear in one.

18 October: Recorded my memories of 1914 at the BBC Studio in Seymour road [Plymouth].

This superb series of programmes, The Great War, was made for the 50th anniversary of the First World War. They were revived for the 100th anniversary in the autumn of 2014. (For HW’s full-length interview see BBC iPlayer.)

After a while Kerstin agreed to a Devon ‘visit’, taking over what had once been Ann Thomas’s role of combining secretarial duties with that of companion. HW recorded on 14 November 1963:

Have been revising Part One (all, so far, of No. 12) in the hut. I read first three chapters of The Man Who Went Outside [last revised 1958 from previous recasting]. Dilemma: autobiography or Phillip.

He collected the trunk full of Lucifer before Sunrise material, left the previous April with Ernie Martin. But he and Kerstin were not really getting on very well together. Kerstin was slimming by more or less starving herself, which made her difficult to live with. At this point HW went off for a foolhardy walk on Dartmoor in pouring rain to get ‘first-hand’ material (for The Gale of the World).

On 21 November at the field HW got out his Scandaroon material ‘after some years’ (a small insight on what was actually to be his last book, published in1972) and found it interesting. On his return to the Ilfracombe cottage he found Kerstin drunk on gin and whiskey, and held her head while she was sick:

I always was my best looking after people – my men in France etc. . . . I guess I am getting ready to create again – the lonely artist, like Wilfred Owen’s “Greater Love” – in a small way.

HW was busy with various projects – among them finishing off the filming with John Irving. Kerstin became increasing difficult and decided to return to London earlier than the planned date of 16 December. HW was somewhat in a quandary because he had promised to judge a school essay competition and had 200 essays to read. He actually palmed them off onto Margery Mitchell: the Mitchells had been stalwart supports for many years.

As 1964 opened, HW was in London, but frenetically rushing around all over the place – to Kenneth Allsop in Hitchin and then down to Petre Mais in Brighton.

5 January 1964: No writing done yet, beyond a couple of pages of outline for Part 2 of 12.

He returned to Devon on 17 January, and the following day:

Spent late morning & afternoon in the hut, & prepared (but did nothing) to continue the synopsis of No. 12.

21 January:To field & worked on details of 12 – getting notes together, & book-sources: Goodbye West Country etc & biography of Mosley.

He then went back up to London to stay with Mary Hewitt: a cousin of his first wife Loetitia and one of her bridesmaids, a very lively and attractive woman – and quite a coquette. The idea was that she would provide a stable base for him to work from.

23 January: Tried to reassemble the bits and pieces of The Phoenix Generation on my bed . . . [but] the impulse seems to have gone. The Imagination is a clutter of resentment that I am left by myself: the warm base, from which to arise in flight, is gone. [HW here identifying himself with the phoenix.]

28 January: I began to write again this morning (sitting on bed in my little room at 74 Queen’s Gate) at 10 am after my usual cold bath . . . I wrote until about 5 pm . . . on no. 12 novel, The Phoenix Generation, six chapters of which I had completed by July 1963 when I broke off to go to Ireland. I rearranged the narrative, making Phillip’s American scenes sandwiched (as originally written but altered later) between the Felicity–Mrs. Ancroft-Fitzwarren scenes when F. learns she is pregnant. . . . I plan to [include] The Man who Went Outside & conclude No. 12 with this. It will mean condensation, i.e. planning. [‘The Man who Went Outside’ is a title of the unpublished work concerning the farm era – and is part of the large amount of ‘Lucifer’ material now held at Exeter University.]

Once begun, HW got into a rhythm of work, although he was still ‘mooning’ (his own word!) after Kerstin. He was at this time using Eric Watkins as a sounding board – but not necessarily paying any attention to Eric’s comments. Eric was dubious about the inclusion of the Mosley speech – HW pointed out that this was a novel, ‘& a character called Birkin makes the speech’. But he did see the point:

5 February: I broke up the long quotation of Birkin’s speech [n.b.: this was taken from a book, for HW had no connection with Mosley until late 1937 – again, see Anne Williamson, ‘Rise & Shine Again’, HWSJ 48, September 2012, section II, pp. 42-50] with various intrusive incidents – Cabton arriving, Coneybeare on the jag, etc. It all fitted into place & became alive – ‘like Tchekov’ as Eric Watkins said later.

When he read this new section to Eric, it was pronounced: ‘very fine indeed – your best so far: taut – ranging – & speedy’. He is still pining after Kerstin, but quite bizarrely meets a girl who offers him sex as a consolation. He arranged to meet this girl at the ‘Queen’s Elm’ – a pub in Fulham road – the haunt of the artistic set at that time. She does not appear but instead he meets there:

an Irish girl, 27 years, who has written a novel accepted by Calder: BERG, by Ann Quin. I invited her here [Savage Club] to dine tonight . . . found she and I were suited. Panic of the spirit arose. I told John Deeney [a club member] ‘I seem to love this Irish girl.’

The next two days were spent at her flat, mainly lying on her bed with their arms round each other. So began his fiery affaire with this seemingly talented and extremely neurotic young writer, who eventually (long after their affaire had burnt out) committed suicide. Ann became Laura Wissilcraft in the final volume of the Chronicle, taking over the very similar persona of his original character who appears the Chronicle novels of the farm era (to be covered later).

|

| Ann Quin |

HW returned to Devon on 27 February, travelling down with Maurice Renshaw (Margot’s brother, who was a good friend to HW throughout his life) and staying with Lady Renshaw in Instow, before returning home the next day.

A memo note at the end of February states:

I have got to Part 2 of no. 12 – i.e. to Chapter 8, where Phillip is in the field above Malandine, planting trees, November 1931.

At the beginning of March he noted that he was writing the ‘Gartenfeste’ part of No. 12. On 7 March he left for Bungay, staying en route with an ex-First World War comrade, to attend the wedding of his son Richard to Anne (myself!), but returning immediately after the ceremony to London and the arms of Ann Quin.

On 11 March he met with a journalist (the editor?) of the Evening Standard and agreed to write ‘Five articles on 1914-18 for £500 – each 850 words.’ A trip to the battlefields of the Western Front was arranged.

A further memo at the end of March notes: ‘Payment for Five Evening Standard articles to appear in August 1964 - £500’. This memo also notes: ‘Marconi article £100. ½ hour programme Dan Farson £100.’ Further: ‘Weeks, $1000 for Salar’ (this was for a US paperback edition). These contracts helped to reassure him that, despite all his emotional turmoil, he was not, as was his greatest worry, finished as a writer. He was now beginning to come out of the ‘writer’s block’ caused by the intense shock of the recent events that had overwhelmed him.

He finally returned to Devon (having met with Ann and Kerstin and others with continual emotional turmoil) on 23 March: two days later Ann arrived to stay but her neurotic character soon became dominant and she left again on 1 April: ‘All fool’s day indeed!’

He began work again with some difficulty on no. 12:

5 April: I worked all day on 12 & did about 2000 words on Chapter 11 – Hetty’s illness & death; final party at Monachorum & burning of the Crystal Palace.

But on 8 April he went back up to London, where, after initial euphoria with Ann Quin, her neurotic behaviour flared up again. So this very bumpy see-saw situation continued, and he found it all very difficult.

17 April: I forget what happened. Perhaps the above [somewhat tumultuous] entry was today.

Or did I finish my novel today? (No 12)

That he did is confirmed by a note in his Desk Diary (appointments): ‘16 April – 12 finished’:

He returned to Devon on 21 April, but travelled back to London again on the 30th, to persuade Ann Quin to accompany him to the battlefields with the Evening Standard photographer. She agreed but then changed her mind, and in panic he asked Kerstin to go instead. HW and Kerstin were away from 5–9 May. On his return the initial meeting with Ann was good, but again deteriorated quickly. After a few days he escaped down to us in Chichester, where we rented a very small flat, and thoroughly enjoyed walking around Kingley Vale, the National Nature Reserve where Richard was manager.

Back in Devon, he began work on no. 13, noting at beginning of June that ‘13 is finished’! (This cannot have been literally so, of course, even though he was reusing previous material.) During June he went back and forth from Devon to London, bringing Ann Quin down to Chichester for a short visit. He went off to a PEN meeting in Oslo for a week from 21 June, mentioning that Alec Waugh also there. On his return Ann was due to leave for Greece. At this point HW decided he had caught a venereal disease from her – and told her so as she caught the train to depart. Ann became furiously hysterical, perhaps understandably so. He came down to us and told us the whole sorry tale. There was, of course, no disease whatsoever.

4 July: [Working at Field, writing, cutting grass etc.] I am revising Part One of no. 12 – really ‘finalising it’ this time. It needs truing up, & Felicity is now a girl who suffers because Ph. does not or cannot make extended love to her – kisses, tongue, licking etc – before entering. She gets cramp (because he does not enter being put off) & has to take tablets.

This is all exactly as has been the case in the tempestuous affair with Ann Quin, noted in detail in his diary. HW is not sure if this really fits Felicity’s temperament – however: ‘Anyway, it’s written now.’ (This scene, and others of a very modern sexual nature, was part of the material which I later suggested he must remove: they jarred most dreadfully with his normal style: some passages crept back in with his final revision!) While doing this particular revision he also notes that he is reading No. 14 to Christine, and recasting that as well.

11 August: Worked on last part of 12 – Roseate Tern chapter etc. [also working on 14]

17 August: Am trying to add to Part III of 12.

The plan: – Fr. Lawrence

Felicity

Coneybeare (returns to Runnymeade)

Tim Coplestone

The family – basis of Community farming

On 4 August he gave a lift to two 18-year-old girls. One of them later contacted him, and by the end of August she was typing for him (even though Elizabeth Tippett was his official typist), and he was paying her living expenses. This girl was Sue Gibson.

1 September: Packet of Tss, beautifully typed, from Sue Gibson.

2 September: I finished the added scenes, letters & dialogue. Copied letter from my mother to me (Hetty to Phillip about Felicity and her baby) . . . etc.

3 September: [At Field digging potatoes.] Did some work on 12, adding “Brother Laurence” wise sayings.

7 September: Recasting chapter 12 of 12. It is wrong. [He must have sent this off to Sue Gibson for typing.]

Memo, 12 September: Wondering where Chapter 12 Birkin for Britain! is – SG not sent back.

18 September: Still no packet from Sue G. (Ch. 12) BUT Liz Tippett’s packet came back from Cornwall. So now all I have to add is the missing Birkin for Britain chapter: & No 12 is COMPLETE.

19 September: Packet from Susan. Good girl. I finished No. 12.

21 September: To funeral of DOUGLAS BELL (L.R.B. 1914). [These two men had remained friends and HW had greatly helped Bell publish his own book A Soldier’s Diary of the Great War (1929).]

HW returned to London and was seeing Sue Gibson, but difficulties are obvious. He also saw Kerstin, who told him she was getting married later in the month (which he appears to have taken without a qualm!)

On 13 October HW received a thirteen-page report on The Phoenix Generation from Malcolm Elwin (his original reader at Macdonald), with a summary of each chapter, noting errors and construction faults. He also learned that Waveney Girvan, the founder of the West Country Writers Association, was dying, aged 54, from liver failure. On 16 October he recorded at Ealing Studio his Armistice Memories at Landguard on 11 November 1918 for producer Julia Cave (who had interviewed him the previous year for the Great War series). He continued on to Bungay, returning on the 24th for Kerstin Lewes’ marriage to Hegarty (first name unknown), then on down to Chichester to me (Richard being in north Norfolk for a few days).

25 October: Pleasant here. I started work on no. 12.

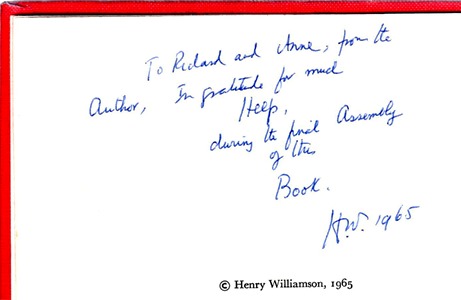

So began my own small involvement on this book, reading, criticising, and suggesting cuts, etc. As a token of thanks he gave us an inscribed copy on publication:

Here we see the sorting out of the Ann Quin ‘sex scenes’ overlay on to Felicity:

26 October: Working on no. 12. Have to recast or rather true up Felicity. F. to be simplified & the A.Q. tensions-mental-nature removed.

27 October: Working . . .

31 October: Working continuously on no. 12. What I do pleases, & releases me.

2 November: Gave Anne, for a present, for a new maternity dress, £10/-/-. [The money was for housekeeping and help given: it was spent on a maternity dress as I couldn’t afford one!]

3 November: Working. Part One finished, and most of Part Two. The cuts arrange themselves – they have no significance – they drop out of their own lifelessness (to the story) as I proceed. [These were discussed and mainly suggested by myself – especially the USA visit material which was an easy way to cut the book’s extreme over-length.]

4 November: Finished Part 2.

5 November: Worked all day on No. 12 (Part Three) & finished at 10 pm. It is now good, and a novel. 120 pages of the original 700 have fallen by the way & deserved to. . . . Tomorrow I go by train [to London for day – return Chichester] for dinner Chyebassa 1914 old Comrades. [For the significance of this see The ‘Chyebassa' re-union dinners.]

6 November: [HW collected post from his club, learning that Waveney Girvan had died. He attended:] Dinner of 1914 Old Comrades at Grace’s Hall – Duke of Gloucester the chief guest, Colonel of the Regiment. This 50th anniversary dinner is the last.

He was unable to contact Sue Gibson, whose friend (with whom HW knew she shared a bed) was apparently ill. He began to realise that she might be lesbian and that he had been chasing a veritable pipe-dream; and indeed she did eventually admit that this was so. Sue Gibson was later, as Sue Caron, to become notorious as the author of erotica such as Lesbian Love and A Woman's Look at Oral Love, and as editor of the ‘top shelf’ magazines New Direction and In Depth. The journalist Robert Chalmers memorably commented that she ‘matched the prolific output, if not the literary invention, of Charles Dickens’. She published some of HW’s passionate letters to her the day after his death in the News of the World. When we pointed out she had broken every law of copyright, Gibson turned to Fr Brocard Sewell (whom she had met through HW), who in due course arranged for them to be turned into reported speech and published them under the Aylesford Press imprint (Caron: A Glimpse of the Ancient Sunlight, 1986).

The next day HW returned to Chichester, collecting his car and driving on down to Devon. He contacted Liz Tippett, asking if she could type No. 12 immediately. He also sent me a cheque for £50 for ‘reading and help’. However, on 11 November he was again ‘Recasting, quite new, Part Three of 12.’ He now heard from Sue Gibson, and so was happy again but:

Mainly, no. 12 is being shaped (Part 3) & now is real, strong novel.

At this time Ann Quin returned from Greece/Corfu where she had taken a young lover.

18 November: Posted Part II of 12 to E. Tippett. Wrote the part where Mrs. Ancroft & Fitz arrive at the Old Manor in East Anglia, finding Bro. Laurence & Felicity there with Phillip. It moved me to tears.

25 November: Finished Part 3 of 12 & posted to E. Tippett.

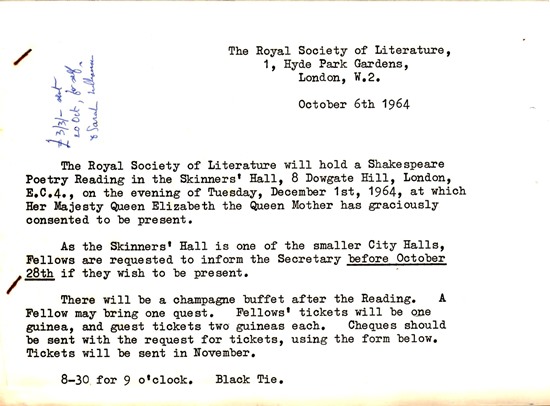

He then went up to London, having been invited to attend a special poetry reading organised by the Royal Society of Literature in the presence of the Queen Mother:

1 December: My birthday, 69 years old . . . To Skinner’s Hall to hear poetry readings. Was presented to Queen Mother . . . Rab Butler as President of the Royal Society of Literature stood next to her.

He had taken his daughter Sarah with him and in turn (against all normal rules of state etiquette) he presented Sarah to the Queen Mother. Her Majesty had asked him if he liked the readings, to which he answered ‘Yes, Ma’am’ – but adding in his diary that he had not!

|

|

L to R: Sarah Williamson, HW, HRH the Queen Mother, and the Conservative politician R. A. B. Butler, always known as 'Rab', later Baron Butler of Saffron Walden |

HW's own inimitable inscription on the back of the photograph reads: 'Sarah Williamson, HW, Lady Birkenhead's arm & left bosom, H.M. Queen Mum, Some Court Gangster, Lord Butler of Trinity House, a Strange Interstellar Object, Krawling up His Lordship's Koat-jacket.'

The next day:

2 December: Meeting at Buckingham Palace, Prince Phillip, Wild Life World conservation. I went in with John Rothenstein. Met Cyril Connolly, Eric Linklater, Lord Gladwyn & others.

This concerned an important World Wildlife Conference that was held to increase awareness of the problems in conservation of wildlife, the chief protagonists being Prince Philip and Peter Scott.

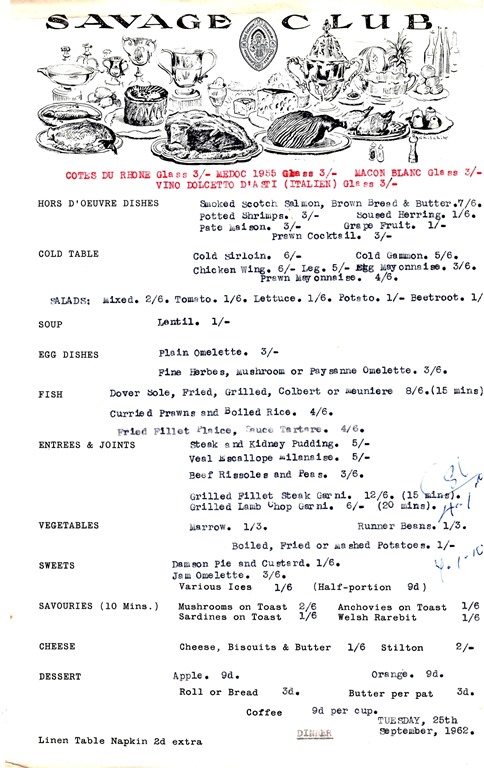

The following day he started sittings to have his head sculpted by Anthony Gray, a fellow member of the Savage Club, who two years previously had drawn a quick portrait sketch of HW on the back of a Savage Club menu, inscribing it 'To my bold bad Brother Savage Henry'; the menu itself is worthy of reproducing here (linen table napkins 2d extra!):

The head was not to be completed until 1968 – the following photocopy of a photograph was supplied by a press agency, titled 'Sculptor Anthony Gray completes his bust of Henry Williamson at his Stamford Bridge Studio', and is dated May 1968:

The finished head is a powerful likeness; its current whereabouts is unknown:

|

| (Photograph by John Bignell) |

On 9 December:

As President of the W. Country Writers Asn I turned up at Lady Marden’s flat for a committee meeting.

So we learn that he has taken over this position from the late Waveney Girvan. It was at this meeting that the first arrangements were made for the WCWA Congress meeting to be held at Exeter the following May, which was to incorporate HW’s presentation of his ‘Devon’ manuscripts to Exeter University. HW was to organise this. And so he did – very successfully – though not without a great deal of panic at times!

There is no further mention of The Phoenix Generation until an entry in his ‘Tablet Diary’ for 9 September 1965:

I finished page proofs of Phoenix & posted them with galleys to Macdonalds.

Then a final entry on 28 October:

*************************

There are some occasional small discrepancies or errors in this volume. (I will try and pick them up as I proceed.) As explained in the background section, HW was under considerable strain while writing this particular book, which is particularly complicated anyway, and for which he really needed even more uninterrupted concentration than usual. One can only admire his dedication to his task in such circumstances.

The time frame of The Phoenix Generation is 1929–1939, an unusually long period for one of the Chronicle novels. The book also uses (more or less ipso facto) material from previous books covering the same period and which were actually written during this set era: Goodbye West Country (1937), The Children of Shallowford (1939), and The Story of A Norfolk Farm (1941), but here woven into the fictional structure that HW’s creates around Phillip’s turbulent life (as his own!) and so appearing in a completely different light. The plot is particularly complicated, or rather it covers complicated material, and therefore needs considerable analysis to clarify HW’s purpose.

We left the previous volume, The Power of the Dead, as Hilary Maddison announced he has sold the family farm (on which Phillip was currently dependent for home and living) to the War Department, so abandoning Phillip to his writing – just at the point that he had decided to concentrate on farming. Note that throughout this present volume Phillip perversely blames himself for failing the farm, which was not really the case – although perhaps his divided attention was one of the reasons Sir Hilary decided to sell.

Part One: FELICITY

As this volume opens much has changed. That a new dynamic is driving the action is apparent by the opening scene. The date is unusually specific: 30 May 1929 – the day of the General Election. Phillip and Piers Tofield (based on John Heygate) arrive in a London street in Phillip’s newly acquired Alvis Silver Eagle sports car (HW’s Alvis was not actually bought until June 1931). They are to attend a party given at Selfridges, the well-known Oxford Street store, hosted by its owner, George Selfridge, to see the election results come in. (There is nothing to suggest that HW attended this party: he either knew someone who did – possibly Heygate himself as roving journalist – or read about it in the press.)

As Piers and Phillip arrive they see a yellow Rolls-Royce, the familiar property of the sporting peer the Earl of Lonsdale: except that this car has been bought by ‘a small dark man wearing opera hat and cloak’. So we meet again Dikran Michaelis, in real life the colourful Armenian writer Michael Arlen, whose books HW rather liked and with whom he obviously empathised (Michaelis/Arlen also appears briefly in Devon Holiday).

At this party Phillip meets Lady Julia Abeline, whom he had last met, when recovering from the effects of mustard gas, in the Royal Tennis Court ward at Husborne Abbey towards the end of the First World War (see A Test to Destruction, vol. 8 of A Chronicle of Ancient Sunlight).

As the evening progresses so more and more ‘Labour Gains’ are announced. Phillip is glad:

No more hard-faced war-profiteers becoming knights, baronets, and peers giving millions of pounds for Lloyd George’s ‘honours fund’ while denying the workless ex-soldiers who had broken the Hindenburg Line and now were breaking their hearts on the dole.

HW is setting out here his 1920s left-wing socialist political stance, held and caused by his experiences in the First World War, as is shown particularly in The Pathway (1928), called The Phoenix in this volume, which he frequently referred to as being infused with Leninist doctrine.

The briefest mention of the history of the Labour Party at this point is possibly useful to explain the importance of this election. The Democratic Socialist Party had been formed in 1900, becoming the Independent Labour Party (ILP). In 1922 it overtook the divided Liberal Party led by Lloyd George (prime minister 1916–22), and in 1924 formed a minority government with the Liberals under Ramsay Macdonald who had joined the ILP in 1894, and now became the first Labour Prime Minister. His government failed fairly quickly and the Conservatives came into power under Stanley Baldwin. Now, in 1929, Labour regains power, again forming a minority government with the support of the Liberals, with Ramsay Macdonald as Prime Minister and Philip Snowden as Chancellor. HW seems to be making a slight error in referring to Lloyd George as a scapegoat at this point although his strength of feeling is apparent.

We learn that Lady Georgiana Birkin (Lady Cynthia Curzon) takes a Staffordshire seat, while her husband Hereward Birkin (Sir Oswald Mosley) has retained his Birmingham (Smethwick) seat, both with good majorities. Mosley had first been a Conservative MP in the 1918 election at the end of the First World War but quickly found their actual policies unacceptable, and had crossed the house and joined the ILP. Following this election he is made Chancellor of the Duchy of Lancaster (Crown Property & Revenue) and junior Employment Minister.

Phillip meets at this party a ‘grey moustached man’ who introduces himself as ‘Runnymeade’. Runnymeade is a drinker and plies Phillip with a large whiskey, which, on top of the champagne he has already had, is disastrous! (Bill Williamson told me in the early 1990s that Runnymeade is based on a Captain Mordaunt Goodiffe, who lived in Brancaster on the north Norfolk coast, but there is no reference to anyone of that name in HW’s archive. There is one reference to a ‘Col. Brindle’ in August 1939. Whomsoever, HW did not actually meet this man until after he moved to the Norfolk Farm. As we know the Chronicle is highly fictionalised at this stage.)

Phillip spends the night with Felicity (ensconced in a hotel). The description of their lovemaking here relates to my earlier comments about Ann Quin in the background notes. As stated, most of this material was removed – but some, luckily very toned down, added back in once HW was back in Devon! (HW had not actually met Ann Thomas, on whom Felicity is based, at this point.)

The next day Phillip returns to Skirr Farm with Felicity, by train, leaving the newly bought but second-hand Alvis to be repaired. (The first owner of HW’s Silver Eagle was Whitney Straight, the well-known rich American Grand Prix racing driver and aviator; the car had been driven hard, and there were constant problems with it. Straight led a colourful life. In the Second World War he joined the RAF and fought in the Battle of Britain. Shot down in 1941 he was captured, but escaped and made a ‘home run’ via Gibraltar. After the war’s end he became the first CEO of the British Overseas Airways Corporation.)

New resolutions about work routine have been made. But Lucy informs him that Piers has telephoned to invite him to go sailing at his local yacht club, and will pick him up in his two-seater Aston Martin. In this pile the two men, with Felicity and Piers’ mistress, Gillian (Gwyneth Lloyd, film-star; Heygate actually met her later than this at the UFA film studio in Germany: at this time he had only recently married Evelyn Waugh). After a while Phillip sees a river and asks Piers to stop for a moment.

The car drew in under an avenue of lime trees. Phillip climbed the tarred railings, and was in a park. He strode to the bank. Water flowed glass-clear. . . . Beyond, among trees, was the long thatched roof of a house.

We learn in the next chapter that this is ‘Flumen Monachorum’, 18 miles south of Fawley: readers will recognise this to be the Shallowford cottage to which HW did indeed move in 1929. In the garden he sees an elderly man and a woman. A cropped version of the earliest photo of Shallowford gives this image:

Before moving on Phillip establishes that the cottage belongs to Lord Abeline, whose wife he had fortuitously met at the Selfridge party. They continue to the yacht club. This is on the south coast (of Hampshire) and is placed on or near Lymington, where John Heygate’s father lived, and where John was a frequent visitor, and HW himself made several visits. John was indeed a member of the yacht club there.

At the club they meet up with ‘Boy’ Runnymeade, sitting alone, drinking whisky and soda. Piers departs to take part in the race.

HW is here drawing on (transposing) his experiences of similar scenes at Instow Yacht Club, where he frequently sailed in his little dinghy Pinta, and where Sir Stephen Renshaw and his wife lived (parents of Margot Renshaw), on whom the Abelines are based.

Runnymeade invites Piers and his small party to dine at the ‘Castle’. (One can place this as being Hurst Castle, situated on the end of the spit off Milford Haven to the west of Lymington.) Piers notes that there will be a crowd arriving later from London, the Russian Ballet Company, as the ballerina, Stefania Rozwitz, is Runnymeade’s mistress (see HWSJ 48, September 2012, p. 61, Note 5).

The arrival of the ballet company at the Castle and the subsequent party are almost certainly based on a party HW attended at the time he was writing this volume, when the Ballet Rambert performed in Barnstaple, given by the Mayor and Corporation (hence the ‘chamberlain’ of the novel). A further source for this somewhat surreal scene is undoubtedly the well-known ballet Les Biches (The Hinds, but sometimes translated as ‘heifers’ as in HW’s story here) which Bronislava Nijinska (Nijinski’s sister) brought to London in 1924. In the novel Stefania has known, and still knows, Nijinski and danced with him in Le Spectre de la Rose. The dancer in real life who danced this with Nijinski was Tamara Karsavina. Karsavina’s background fits that given to Stefania: she married an English diplomat and lived in London (but almost certainly the scenario of the novel is entirely fictional). It is all a masterly juggling act by HW!

After they have eaten, and in response to Phillip’s story about his heifers, the dancers spontaneously dance out the story of Rosebud, which we can transpose into Les Biches.

With the dancers has arrived a man called Archie Plugge. He is based on Heygate’s friend Bobby Roberts, who was with Heygate when he first met HW in Georgeham, and was one of those involved in the Georgeham village sign incident. Plugge had appeared briefly in the previous volume, The Power of the Dead.

The Alvis gets a rebore, and then, keen to give it a run, Phillip takes Lucy to see the house he has found at Flumen Monachrum. He has to give up the farm tenancy by Michaelmas and does not want to live in Fawley House,which is being converted into flats. He knows the occupation of the land by the military will be a constant reminder of the First World War:

Crack of tank cannon, and splintered trees.

He tells Lucy that the house is owned by Lord Abeline, who lives in the adjoining Abbey. Lucy does not tell him that Lord Abeline is her cousin by marriage (as was Sir Stephen to Loetitia). In real life, HW and Loetitia moved to Shallowford on the Castle Hill estate of Lord Fortescue at Michaelmas 1929. (The Fortescues do NOT have any role in the novel.) The concept of the Abbey almost certainly derives from Hartland Abbey on the north-west Devon coast, a place of which HW was very fond. Two miles of fishing go with the tenancy of the cottage – as they did in real life.

Phillip then drives Felicity to London. En route they stop and make love in a wood. Felicity is immediately sure she will be pregnant. (She’s not – but this establishes her longing for a child, as was the case with Ann Thomas in real life.) Phillip visits his parents, who are to occupy one of the new flats at Fawley House, to explain that he will actually be moving but will still be nearby.

Just after the move to Flumen Monachorum has taken place, an old soldier arrives asking for employment. Rippingall had been working for the Rev. Scrimgeour, but has lost his job as he suffers from bouts of ‘malaria’. So enters into this tale the real life Cecil Bacon, previously employed by the vicar of Georgeham but dismissed after the latest of many drinking bouts. Bacon has previously appeared as ‘Coneybeare’ in The Children of Shallowford. Initially Rippingall works hard and is a great help in house and garden, but gradually deteriorates. We learn later that Rippingall had also once worked for Boy Runnymeade.

On p. 38 we are given a fuller description of Monachorum House (named after the monks who once inhabited the Abbey): very recognisably Shallowford.

Monachorum House stood among trees, a couple of hundred yards outside the deer park of the Abbey, home of the landlord, built of chalk and limestone blocks and thatched. Pear, peach and greengage trees grew against the south wall, with holly hocks and sunflowers. It had paths of limestone chips, and two small lawns. Lucy loved it.

We are also given a brief glimpse of the children: ‘Billy, the elder boy, was now rising five years. He and Peter and tiny tottering Rosamund (‘Roz’ to her brothers) . . .’ But mainly here we learn that when it rains non-stop in the autumn, the house is damp – and the fireplace is useless. Phillip gets permission from the estate clerk of works to alter the fireplace, and he designs what he considers is the perfect shape for maximum heat and minimum smoke. (This was an obsession with HW!) When the work commences Phillip asks specifically that the lovely warm blue Delabole slate slab be kept. He leaves for London to make his first (nerve-wracking) broadcast for the BBC. On his return he finds, to his intense annoyance and chagrin, that the slate has been smashed up and removed, with a bare and cold concrete hearth now in its place. Neither Lucy nor Ann had done anything to stop this. This is exactly as in real life.

Everything is depressing: the women do not keep things tidy or clean, and Rippingall’s drunken episodes make him unreliable. The newspapers are full of depressing news about unemployment, while the low winter sun never shines over the leafless trees that overlook the valley. However –

. . . with the primroses Felicity came back.

But she is soon worrying about getting fat, and tries to slim.

All go daily over to Fawley to prepare the ground floor flat for Richard and Hetty Maddison. Richard is pleased about returning to his family home, but he also decides to keep on the London house as a precaution, and as a pied-à-terre for Phillip’s use when in town.

Phillip, supposedly writing his trout book in the orchard, reads the newspaper report about the resignation of a junior minister, Birkin, with the headline:

GREAT SPEECH TO THE HOUSE

This is Oswald Mosley’s speech of resignation from his post as employment minister in the Labour Government on 28 May 1930, after his proposal to combat the recession, known as the ‘Mosley Memorandum’, had been rejected. Many political commentators of various persuasions considered then (and since) that Mosley’s proposal (a Keynesian* monetary solution) was extremely sound and would have met with success. The leader paragraph in the fictional Crusader (actually from the Daily Telegraph – but other papers also) shows that Mosley’s ideas were considered most favourably, and cheering from all sides of the house is noted. Some modern commentators have opined that he was a great politician who could have led both the Conservatives and Labour, but was thwarted by the establishment. (It is quite important to understand this in the light of what eventually transpired.)

(* John Maynard Keynes (1883-1946), British economist, anti the Versailles Treaty and advocate of public spending to alleviate the Depression. Interestingly Keynes was married to a Russian ballerina.)

Phillip’s reading is interrupted and interspersed with various domestic scenes (recollect HW’s diary entry for 5 February 1964 about tackling this scene): Hilary and Irene arrive unexpectedly (and of course argument ensues), Cabton also, who invites himself to fish against Phillip’s wishes, while Rippingall is drunk and announces he has seen the ghost of the ‘Rascal Monk of Monachorum Abbey’ who is asking where Miss Felicity is living. This seemingly surreal drunken fantasy turns out to be substantive. To escape all this Phillip goes off on his own.

Left alone Felicity decides, in order to help Phillip, to tidy up his writing room, which includes throwing out a pair of precious sand-shoes that had belonged to Barley (the last thing she wore) and which were kept locked in a wall-cupboard. On his return Phillip is distraught: luckily he retrieves them before they are burnt, but he drives off in despairing state. Felicity also leaves. This scene is based on Christine’s radical ‘refurbishment’ of HW’s Writing Hut and Studio in November 1962 (see the background to The Power of the Dead) just before she actually left him, which caused HW great distress. For Barley’s shoes substitute the real-life letters of T. E. Lawrence which were not found for several days.

Felicity has fled to her mother’s home, where ‘Fitz’ is also present: her upset state is very obvious. Fitz soon deduces that she is probably pregnant.

Phillip meanwhile has decided to visit the battlefields and sends a telegram to Piers to say he will be staying at the Skindles Hotel, Ypres (this is not the original famous ‘Skindles’ of First World War fame, which was at Poperinghe).

The two men visit Toc H in Poperinghe – the famous Talbot House where Rev. Tubby Clayton held his chapel services to comfort men going to and coming out of the Front Line. There follows several pages of Phillip’s thoughts as he retraces his wartime haunts. This passage relates to the visit HW made in June 1927 with his brother-in-law, William (Bill) Busby, husband of HW’s sister Doris (Bob Willoughby of the Chronicle), and including HW’s honeymoon visit of May 1925, which HW wrote up first in a series of articles and then incorporated into The Wet Flanders Plain (see entry for details).

(Note too that in May 1930 – the time of this present novel – HW’s The Patriot’s Progess was published to great acclaim, while The Village Book also appeared at end of July 1930. These are not mentioned in the novel.)

Phillip cannot face the idea of the new Menin Gate (the Menin Gate Memorial opened in 1928). His mind-vision overflows with the ghosts of the men who had passed through and down the Menin road.

No, it was not men; it was a force that was passing, like an invisible wind that hurled down brick and stone soundlessly, that filled the Grand’ Place and streets with cries and shouts and the screams of the dying, yet all was without sound. . . .

He sat there, the wraith of himself merging with remembered darkness rushing by, yet stagnant amid soundless cries, viewless flashes of field guns lighting broken wall and scattered rubble, the subdued fears of men moving in broken step, laden and sweating, through the gap called the Menin Gate.

Into these harrowing memories HW inserts a scene where Felicity’s mother, Mrs Ancroft, ponders over her own story. We learn that although she has told Felicity that her father had died in the war, this was not true. Her husband in a fit of extreme anger against his wife, had picked up his young daughter and shaken her, and then left the matrimonial home for ever. The husband (not given any name) had joined up, but had survived the war and the last Mrs Ancroft had heard of him was that he was a lay-brother with the Order of Laurentians, working in the Congo. She had refused to divorce him.

This is an interesting background to have substituted for that of Edward Thomas (1878-1917), writer, poet, and father of Ann (Myfanwy) Thomas (‘Felicity’), killed in the First World War. HW would of course have wanted to disguise the fact of ‘Felicity’s’ real identity to a certain extent – but mainly this gave him the opportunity to introduce a new element which adds an important (but hidden) mystic message, as will be seen.

On Phillip’s return from the battlefields, a letter from Felicity informs him that she is pregnant – as also is Lucy. There is also a letter signed ‘Bro. Laurence’ (the monk seen by Rippingall), who has read The Phoenix (that is, The Pathway) and gives his own analysis:

Your hero, Donkin, believes that by a change of thought the blind will see, the selfish will love, the cruel have pity, and the dead of the war will rise again. He is wrong and fails; for although all he meets are stirred for a moment and see with his vision, he is cast out and dies; the living are unchanged, the dead remain dead. But he is also right, and succeeds, for the act of the artist-misfit-messiah, which in this world can only be symbolic, is reality in the kingdom which is not of this world.

Mrs Ancroft wants Felicity to have an abortion (as real life). Fitz states that he will marry Felicity: he had previously made sexual advances and apparently assaulted her when she was a child. There is no indication that ‘Fitz’ existed in real life; HW is merely adding a dramatic element to his tale. All these alternatives are averted: Felicity determines to have her child. Through a letter written by Felicity to Lucy we conveniently learn that she is now living with Phillip’s sister, Doris – as Ann did in real life.

Phillip absents himself from any domestic involvement. He buys a dinghy, Scylla, (actually HW’s boat Pinta) and goes down to the coast to sail, planning eventually to go on westwards to Malandine. He sees Runnymeade sailing with a young girl who looks just like his beloved Barley. Lost in thoughts about Barley and being an inexperienced sailor, he finds himself in trouble. Good description follows as he contemplates death by drowning – but he has been seen and the lifeboat comes to the rescue. (This is based on a similar experience HW had when sailing Pinta out from Instow, although possibly it was not quite so dramatic as this fictional one: see diary entry for 25 June in background section.)

On recovering he learns that the Barley look-alike is Melissa Watt-Wilby, daughter of Lady Abeline (note the sound pun: ‘what will be’), last seen in 1918 aged four (so now 16 or so) when he was recuperating at Husborne Abbey from the gas attack and ‘Spectre’ West’s death by drowning.

Phillip is suffering from writer’s block and further worried that his parents are not happy at Fawley House where there is much disturbance by the army. Then a letter arrives from Felicity announcing the birth of a son, Edward (a clue perhaps to show that Ann was Edward Thomas’s daughter! Ann actually gave birth to a daughter). Lucy has also given birth to a boy, David.

Part Two: MELISSA

Phillip and Lucy are invited to a dinner given by the Abelines at the Abbey, prior to going on to the Hunt Ball taking place at Boy Runnymeade’s domain at the Castle. Interestingly HW gives here some family history for Lord Abeline, which matches that of his real-life counterpart, Sir Stephen Renshaw.

At the dinner he sits next to Melissa and then later dances with her: the next day he sees her at the Hunt, then again in a game of badminton in the Abbey’s Old Stables. Here Phillip meets Becket Scrimgeour, younger brother of the rector. Scrimgeour is based on Kit à Becket Williams, composer and writer on the Pyrenees (whose father and possibly brother were parsons at a parish just west of Barnstaple – see On Foot in Devon) with whom HW went skiing in the Pyrenees in January 1929. Melissa meanwhile writes to Phillip making it clear she is in love with him.

Phillip establishes Felicity in a cottage on Reynard’s Common (one of HW’s childhood haunts: in real life Ann went to live with her older sister Bronwen, widowed and also with a small child, at Tenterden in Kent). Phillip hands over a large pile of correspondence for her to answer on his behalf, including the one from Brother Laurence. He then takes himself off to the family home at Hillside Road to write his book in peace and quiet. Felicity is also writing her own novel. (Ann’s own novel, Women Must Love, Faber 1937, was published under the pseudonym Julia Hart-Lyon.) Richard decides to go up to London to see Phillip in their old home: discovering, to his fury, his two estranged daughters living there at Phillip’s suggestion.

Phillip goes to see Felicity, who tells him that in replying to his fan letters she has discovered that Bro. Laurence is her father. Phillip and Bro. Laurence get on well together. (Explanatory discussion about the importance of the role given to Bro. Laurence can be found in Anne Williamson, ‘Rise and Shine Again (As a Phoenix Regenerated)’, HWSJ 48, September 2012, Section IV, pp. 52-54.)

Phillip visits his father to apologise and they are reconciled. Richard tells him he has decided to return to his London home (note that Hetty has no choice in the matter!), and the two men arrange to go for a last walk together on the Downs, as Richard had done with his father when he was young.

The passage describing the walk is one of the highlights of The Phoenix Generation. It is set by Richard’s memories of walks with his own father. A timelessness hangs over the scene: redolent with Roman marches, ox-drove shepherding, and the whole history of the Maddison family:

This myth of a Roman road, sometimes a wide and cambered paleness, a ghostliness as of grass itself weary of time, pale with the sunshine of nearly two millennia of a dwarf-yellow-star “bursting through untrodden space” . . .

The quotation is from Richard Jefferies – Richard Maddison says that they may indeed have met him on one of these walks.

It is a moving, poignant scene of reconciliation between father and son, who have been at odds with each other more or less since Phillip’s birth. It shows too HW’s great need of reconciliation with his father. It is also a metaphor for HW’s desperate longing for reconciliation between two countries that very soon after this would go to war for the second time in a generation.

After his parents have gone back to London, Phillip sells Fawley House and so pays off his overdraft.

Phillip now becomes very friendly with Lady Julia Abeline and Melissa (George Abeline has vanished from the scene.) He takes Melissa sailing: another gale blows up but this time he acquits himself well. He invites Melissa to join him in London where he is to attend a Birkin rally at the invitation of Piers.

This is a rally of the fictional ‘Imperial Socialist Party’ (ISP) – HW is echoing here the original ILP (Independent Labour Party), which gives us a real indication as to how he saw Mosley at this time: as ‘socialist’ rather than ‘fascist’. Indeed that appears to have been his attitude throughout. It is significant that Phillip attends this rally at Piers’ invitation. (HW did not attend this rally in real life: he is laying down a marker that it was Heygate who drew him into this political arena.) Piers had just returned from Germany where he is working for a film company near Berlin. (Heygate worked for the UFA film studio from early 1932.) The speech HW quotes here is from Mosley’s Albert Hall speech of 28 October 1934. He conjoins details from more than one actual meeting here, and the fictional meeting takes place at a slightly earlier date, but the route that Phillip takes to get to the meeting leads to the Albert Hall. His source for this scene was A. K. Chesterton’s Portrait of a Leader (1937).

Phillip returns home to work on his book The Blind Trout. He is looking for a spirit of resurgence symbolised by clean rivers where salmon will leap in the Thames and the (highly polluted) Rhine. He alludes to the fish as the ancient symbol of Christianity:

. . . as baptism is the symbol of the new consciousness of faith, of hope, of clarity. . . .

The allusion to the well-known passage from St Paul’s ‘Epistle to the Corinthians’ is echoed in various places within HW’s writing, notably in the last volume of the Chronicle; while in April 1943 he wrote an article with this title (‘Faith, Hope, and Clarity’) for the Eastern Daily Press (collected in Green Fields and Pavements, ed. John Gregory, HWS, 1995, e-book 2013). HW’s equation of the original ‘charity’ (nowadays translated as ‘love’) with his word ‘clarity’ reveals his continual search to see as the sun – that ‘Ancient Sunlight’ – sees, without shadow: to seek and find ‘Truth’. Interestingly both George Painter and John Middleton Murry (well-known national literary critics) mention this ‘charity/clarity’ aspect of HW’s writing.

Phillip goes down to Malandine and plants trees there. He is recreating here early work done at his Field at Ox’s Cross, including making a map of the field. The work makes him optimistic: ‘There would never be another Great War.’ He also feels the spirit of Barley, now conjoined to that of Melissa.

Lucy’s father dies after a fall. (In real life Charles Hibbert,’Pa’, died after a fall on 26 April 1935.) Ernest (Frank Hibbert) does not understand the complications surrounding the mortgage, or that the loans (reversions) that the ‘Boys’ have taken out on their home, Down Close, means that there is no money to inherit. Phillip tries to sort it out but only gets increasingly exasperated (all as in real life!). Ernest comes to live at Monachorum.

Phillip, now unable to write, retires to Malandine and his ‘Gartenfeste’. (Michael Coultas, in his ‘Decline & Fall, Part II: Ashes of the Phoenix’, HWSJ 47, September 2011, suggests that HW’s translation of this as ‘Garden Strong-point’ is incorrect. This is not actually right: although ‘Fest’ with a capital ‘F’ is indeed ‘festival’ (or party), ‘fest’ with a lower case ‘f’ translates as ‘firm’ or ‘strong’. That was obviously HW’s intention. What HW wanted to suggest here was the idea of an impregnable refuge such as he had found in his early writing days in his grandfather’s house, and later in his sacrosanct Writing Hut – fictionally transferred here to a field at Malandine.)

There is a heavy fall of snow (which devastates his newly planted saplings) and he gets out his old skis from his original Malandine cottage and goes skiing, but has a fall, twisting his ankle, and so returns to Monachorum.

The next morning Lucy brings him tea in bed – he thinks how sweet she looks: in due course she realises she has conceived another child.

Phillip now settles down to write the trout book, whose form suddenly – at last – comes to him (compare this with the entry for Salar the Salmon). He also starts to keep a journal, which provides a medium with which to record thoughts outside the actual flow of the book. Much of this is culled from his previous writings of the Shallowford era.

The trout book progresses: he reads it to Rippingall and then sends chapters off to Felicity to type and post off to the publisher. But Ernest’s presence is irritating and irksome, and so Phillip returns to Malandine (as HW went off to his Field to finish Salar the Salmon in 1935).

Melissa arrives on horseback. They go for a walk on the seashore at Malandine where they see: ‘a silver shape moving slowly in from the west.’ – the airship Hindenburg, returning from a trip to the USA. HW does not give a date here, but he has moved this quite momentous event back a year to accommodate the sighting into his story. In Goodbye West Country he records seeing this extraordinary sight on 23 August 1936 from Vention Sands (Putsborough/Woolacombe beach). However, although the German airship was seen that day – HW seems to have been in London on business!

Melissa tells him her father is moving to Norfolk (as Sir Stephen Renshaw did), and Boy Runnymeade also. She feels unable to help him, and leaves. Phillip continues with writing at Malandine, not eating properly and exhausted (again, as with Salar the Salmon), until the book is finished. He is then at a loss but Piers writes from Germany inviting him to visit and attend the Nürnberg Rally (as happened in real life).

Chapter 8, ‘Hakenkreuze’ (the German word for swastika: it translates as ‘hooked cross’) relates Phillip’s visit to Germany fairly exactly as HW’s actual visit in September 1935. Piers is working at a film studio near Berlin (as Heygate did at the UFA film studio). Phillip is assigned a ‘guide’ (or minder), Martin. This was Martin Chemnitzer, or Kemnitzer, whom HW referred to as ‘K’. Martin explains the background of current politics and shows Phillip much that impresses him – the new roads, the happy Hitler youth, the Auto-unions (fast racing cars), the agricultural advances, the cleanliness etc. This was a deliberate plan to impress the eminent English writer, and HW was not alone in being swayed by this propaganda.

They leave for Nürnberg in Piers’ Aston Martin (Heygate’s car at this time was actually an MG – his Aston came later.)

They passed over a level crossing with its long barrier pole upright and its skull and cross-bones of warning below the picture of a child’s puffer train.

A photograph of this appeared in Goodbye West Country, where a chapter is devoted to an account of HW's visit to Germany at this time:

At the rally Phillip is pushed out of his seat by a large and seemingly unpleasant man, discovered to be Rev. Frank Buchman (1878-1961; a well-known American evangelist & Lutheran pastor, and the founder of the Oxford Movement, founded in the 1920s).

Piers recognises the Mitford sisters. We are given a description of the Rally, where Goering and Goebbels were also present. Afterwards Piers and Martin return to Berlin, leaving Phillip to go on alone, joining a ‘Press bus’, with more scenes and opinions. (HW did not go to a hotel where Hitler was present, as Phillip does here – it is included for ‘local colour’!). Phillip writes his thoughts as a long letter to Melissa (a useful device) – but never posts it. He returns to the Adlon Hotel in Berlin, and then back to England.

There he learns Lucy has given birth to another son, Jonathan (‘Jonny’) and is still in the nursing home. (In those days a lengthy stay in bed was considered necessary. This child was Richard, born 1 August 1935, a month before HW actually went to Germany.)

Phillip frets about the fact that he is not starting his real life’s work (i.e. the Chronicle) and goes back to his Gartenfeste, but winter is approaching and so he returns to Monachorum. The proofs of The Blind Trout arrive. But hearing that Melissa is at the Abbey packing up ready for the move to Norfolk, he rushes off to see her, to discover it is her 21st birthday. She takes a bath, asking him to scrub her back, but he cannot respond sexually. She shows him photos her father has taken of her school-friends in the nude (presumably his odd behaviour is the cause of his divorce.) He has bought 2000 acres of land in East Anglia, including four farms: Phillip muses that he would like to farm again.

The Blind Trout is published to great acclaim. Phillip thinks to use his royalties to farm:

If Birkin comes to power, farming will take its rightful place in the life of the nation. If Birkin fails to come to power, then farming will be a priority in defence of the nation.

This is an important statement showing HW’s central view on agriculture and its significance both in the policies of Mosley and to the nation.

On 20 January 1936 the death of George V is announced over the radio. Phillip, accompanied by Rippingall, goes up to London to cover the funeral for the Crusader. The grand procession is described: gun carriage, Edward VIII and his three brothers walking behind. Then quoting Shakespeare’s Richard III (and thus its associations):

It was a winter of discontent. At the beginning of March Hitler reoccupied the Rhineland . . .

HW very subtly (and it is far too easily passed over) shows his disquiet about the future through the juxtaposition of those two sentences.

Phillip now intimates to Lucy that he would like to farm in East Anglia, and later, with his father, says that if war occurs then farming will be of great importance, so reinforcing the previous statement. (In real life HW’s farming venture was settled over the New Year of 1936 when HW visited Dick de la Mare at West Runton.) He learns that his mother is ill with cancer in a nursing home (as in real life), and he goes to see her, avoiding his sister Elizabeth, in a poignant scene.

From there, he goes on to East Anglia: first to meet up with a rather strange girl who has written to him, enclosing her poems. Laura Wissilcraft lives at Yperne. HW’s choice of name for this market town is resonant of Ypres – and his thoughts return to his time there. It is immediately obvious that the girl is neurotic to the extreme. (The place was actually Eye in Suffolk, and the girl in the scene – Elsie Anderton – was exactly as described in real life.)

Escaping, Phillip continues to North Norfolk where he arranges to buy three hundred acres of a run-down farm for £5 an acre (1 hectare = 2.471 acres). But we have not heard the last of Laura Wissilcraft . . .

Chapter 10 is entitled ‘Vale’, Latin for ‘Farewell’. Phillip has arranged a farewell party, but wonders, as his mother is dying, whether he should cancel it. He goes to see her, knowing it is for the last time. Back at Monachorum, Rippingall organises the party, particularly the drinks. Among the guests (apart from Phillip, Lucy, Felicity and Ernest) are Brother Laurence, Piers, Melissa, Captain Runnymeade, Lord Abeline (who appears rouged and dressed as a woman), the artist Channerson (C. R. W. Nevinson), Becket Scrimgeour (Kit Williams) and the Rev. and Mrs Scrimgeour. Also the Cabtons arrive, unannounced and uninvited, having been to Fawley and told that a party is being held!

At the end, when most guests have departed, Rippingall tells them that the wireless has just announced that the Crystal Palace is on fire (the actual event occurred on 30 November 1936).

The scene changes. Richard Maddison (we are not told immediately but he has just come from his wife’s death bed) goes to the crest of the Hill, sees the fire and gets on his faithful Sunbeam bicycle, cycling to Sydenham to get as near to the fire as possible.

The description of the fire is one of HW’s magnificent set-piece passages: added to the drama is Richard’s grief at Hetty’s death. He returns to telephone Phillip with the news.

‘Phillip, it’s been simply awful. It’s like Wagner’s Götterdämmerung. Poor mother, like Brunhilde, is at rest. The whole sky is still glowing.’

HW’s mother had died on 18 April 1936. HW conjoined it to the Crystal Palace conflagration to make a truly dramatic scene, a tribute to his mother. That he also intends it as a metaphor for the end of the known, safe, ‘old’ world is obvious when one takes into consideration his underlying thinking: Wagner’s Götterdämmerung ends that world with first fire then flood. We have here the fire aspect: the flood is still to come.

Returning to the party Phillip reads aloud the ‘Threnos’ section from Shakespeare’s poem ‘The Phoenix and the Turtle’. HW is giving here a big clue about the hidden background. In 1954 he had quoted the poem in his essay on T. E. Lawrence (‘Threnos to T. E. Lawrence’, The European, May & June 1954; reprinted in Threnos for T. E. Lawrence and other writings, ed. John Gregory, HWS 1994; e-book 2014) ). He has named Felicity’s father ‘Brother Laurence’. He is associating Bro. Laurence with (as) TEL. It is all a hidden word-association process. (More details can be found in Anne Williamson, ‘Rise & Shine, Part II, HWSJ 48, September 2012, particularly see pp. 52-54.)

Phillip attends the funeral of his mother, but cannot cope with the family get-together afterwards (and then chides himself for his attitude). We learn that Rippingall has now left his employ to marry a widow in Shakesbury. Phillip listens to the abdication speech of Edward VIII on the wireless (11 December 1936). Again HW shows his disquiet:

It was a winter of grief and dismay in a world decaying.

Phillip sees his father off on a world cruise (as in real life), and then, accompanied by Ernest, leaves for East Anglia and ‘Deepwater Farm’.

(It should be noted that Frank Hibbert (‘Ernest’) was never involved in the farm project: it was Robin Hibbert, known as Bin, who actually returned from Australia in the first week of December 1936, and went with HW to the farm the following year. However, this is no way impinges upon HW’s story line here.)

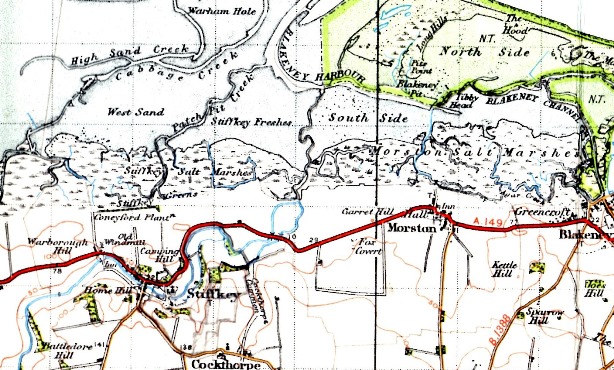

The section of map below is from a contemporary Ordnance Survey map of the North Norfolk coast; the area around Stiffkey is enlarged in the second map. HW's 235-acre farm was just south of the church and river at Stiffkey, with the land extending to the right:

Part Three: WAIFS AND STRAYS

The opening chapter heading of ‘Denchmen’ derives from the Danish settlers (that is, invaders) that populated this area.

The two men are to prepare the farm and its buildings preparatory to officially taking over the farm at Michaelmas, which involves a great deal of hard work. Camping in the cold and dank Old Manor they manage to set fire to the chimney, full of debris from years of jackdaws’ nests. Enter Horatio Bugg who tries to sell them fire insurance. (This is ‘Goitre’ Gidney, whom HW did not like: not to be confused with Billy Gidney, the village blacksmith.)

Phillip settles down to write a description of the farm, and hears wild geese calling as they pass overhead.

The casual eye of the rambler or nature-lover would see in summer, from the high fields, a world of beauty lying before and below him. I can imagine an enchanting prospect, while sitting on the grassy Home Hills, [of] ladies bedstraw and eye-bright, wild thyme, cowslip, and pale July harebell swaying on delicate stalk, while before and below one, the river winds through the meadows, beyond the woods and coverts. Afar lie the marshes and a sunlit line of sandhills below another line of azure sea flawed by a remote whiteness of waves breaking on the shoals of the shallow coast. It is a view beautiful to behold. . . . but to a farmer’s mind . . .

That superb description of the view from the top of the ‘Norfolk Farm’ (Old Hall Farm) at Stiffkey on the North Norfolk coast still holds today. In recent years the farm belonged to Lord Aubrey Buxton, Patron of the Henry Williamson Society; on his demise it passed to his son (now Patron in his father’s stead). James Buxton is continuing to revert the area to a magnificent nature reserve.

|

|

Home Meadows from the pines in 1968 (photo © John Gregory) |

Phillip was being paid £25 by the Crusader for a weekly article (as was HW for the Daily Express, collected in Chronicles of a Norfolk Farmer, ed. John Gregory, HWS 2004; e-book 2013) plus various other articles, which helped him finance the farm. (These are noted with the entry for The Story of a Norfolk Farm.) His idea was to run a small community farm, and these articles bring forth several letters. One of which was from ‘a young man called Hurst, who was working for a private bank in the City’. Hurst, reading these articles, thinks Phillip to be ‘the revolutionary prophet Britain was waiting for’. He intends to arrive the next day. (Hurst is based on John Coast, who worked for Rothenstein’s Bank, the fictional ‘Schwarzenkoph: a name disguised with HW’s usual fairly obvious exchange – ‘roten’ (red), ‘stein’ (stone) changed to ‘Schwarzen’ (black), kopf (skull).)

Hurst duly arrives (self-invited), wearing a badge designating him a founder member of NSDAP (the German National Social Democratic Party, to become known as Nazi) to which he could not be entitled, being too young. Hurst quickly shows that he is very anti-Semitic, and thinks Birkin too weak and lenient, having expelled from his party the rampant anti-Semitic personnel, Frolich (actually William Joyce) and Jock Kettle (real name unknown).

The passages concerning Hurst exactly mirrored real life (again see Anne Williamson, ‘Rise & Shine, Part II, HWSJ 48, September 2012, pp. 44, 45, 46), and is important in establishing HW’s own attitude. Phillip is shown as not liking Hurst or his extreme political stance (‘Hurst is a crank’, p. 259) and is only too glad when his short sojourn ends.

Meanwhile Hurst and his pal Kettle (who also turns up in the novel, but soon disappears again) decide to hold an activist meeting in the nearby fishing port of Great Yarmouth. Kettle has the behaviour and skill of a fairground huckster, but the hardworking fishermen and ‘gals’ want no truck with either fascism or communism and give them very short shrift.

Felicity and Bro. Laurence arrive, Felicity having had to delay due to scarlet fever – in real life it was mumps, and Ann Thomas was alone. Ernest now leaves the farm, to prepare to travel to Australia to join his brothers.

Horatio Bugg visits to exchange (or pump for) information and mentions Lady Penelope Carnoy, a local resident who watches wild birds. We are also told that another visitor has been Lady Breckland, asking Phillip to join the Imperial Socialist Party. (This was Dowager Lady Dorothy Downe, a prominent member of the BUF, who visited the farm on 5 October 1937.) Phillip, needing to get on with his own work, agrees to do so just to get rid of her (as in real life, except that Lady Downe actually pestered HW with more than one visit).

Hurst, having managed to break the gearbox of the lorry by misuse, now departs, to Phillip’s (and HW’s) relief, about three months after he arrived (he goes to work for a more extreme group, as did Coast in real life). But in his place, and to Phillip’s dismay, arrive Cabton and wife, and, following hard on their heels, Bill Kidd, who offers to clean the water system in the Old Manor with sulphuric acid and manages to blow up the boiler (As HW never bought the Old Manor – it was a separate entity – this is all complete fiction.) Phillip decides to do up two farm cottages instead (which was always the real life plan anyway).