THE CHILDREN OF SHALLOWFORD

|

|

| First edition, Faber, 1939 | |

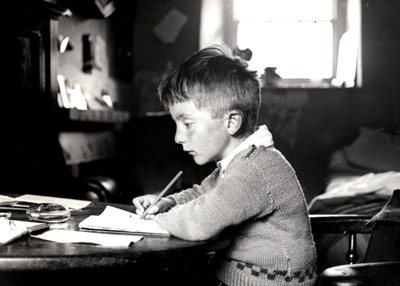

Some family photographs from the Shallowford era

Henry Williamson and Reginald Pound

First published Faber & Faber, October 1939, 8s 6d

(Matthews, Henry Williamson: A Bibliography (Halsgrove, 2004), states September; 4000 copies.)

Illustrated with frontispiece and 16 further photographic plates of the Williamson family.

Faber & Faber, 1959, revised edition, 15s (The Times Literary Supplement review note dates it as late June)

Text much shortened but with also new material, some taken from Goodbye West Country, some fresh; also with an Epigraph by HW updating the lives of the ‘children’. The various changes make this a very different book from the original. (Main chapter changes are noted in 'The book' section below.)

Macdonald and Jane’s, 1978, £5.50; reprint of the 1959 edition (including the Epigraph)

With some new photographs and an Afterword by Richard Williamson bringing the ‘children’s’ lives up to date.

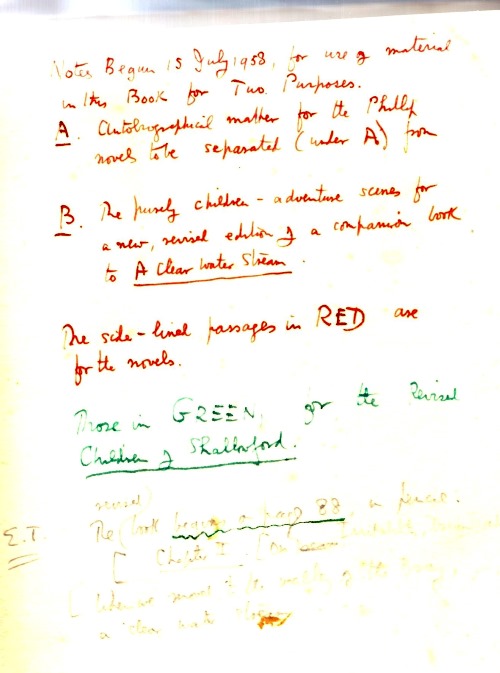

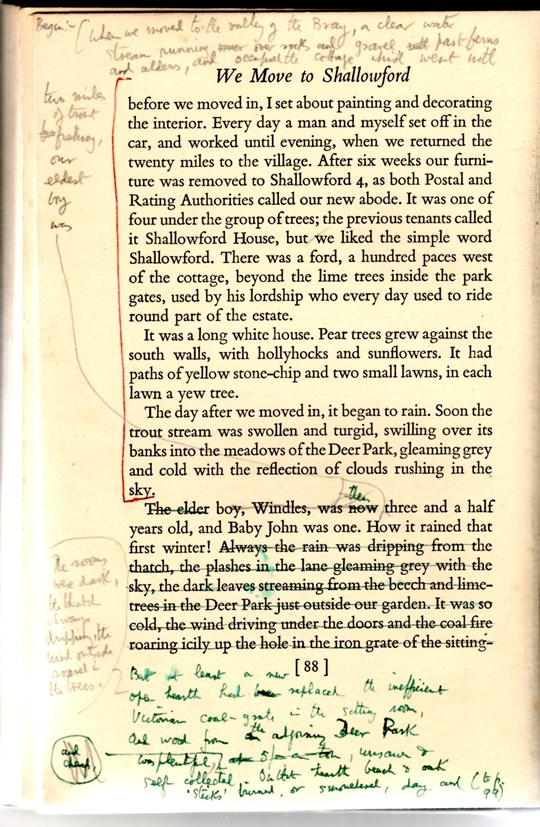

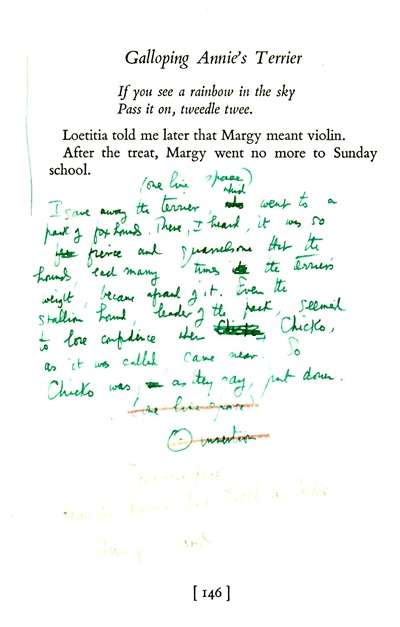

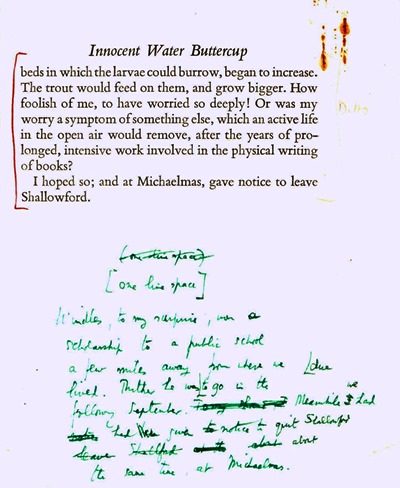

For the revised edition, basically HW removed his own autobiographical and other material that he wished to use in A Chronicle of Ancient Sunlight, so leaving the book more about the children only. He accordingly marked up a copy of the book for his typist, Elizabeth Tippett. His note and some examples of the revisions are shown below:

The last paragraph, which is in pencil and almost illegible, reads:

E.T. [Elizabeth Tippett] The revised book begins on page 88, in pencil.

[Chapter I On Irritability, Dream, and Death

When we moved to the valley of the Bray, a clear water stream

Page 88: HW's draft for the beginning of the revised edition [in the event, this would change]:

*************************

The first edition bears the dedication:

|

To Merriel North Friend of all Children |

The revised edition changes the spelling to ‘Meriel’ and omits the epithet.

‘Merriel North’: The Hon. Mrs Meriel North was a rather odd person to have chosen as dedicatee: she had nothing to do with Shallowford and was an acquaintance (friend) made after the move to Norfolk, living nearby. It is evident that HW was very impressed with her to begin with, but later found her rather arrogant (county gentry) attitudes difficult to take. She is portrayed as Lady Penelope Carnoy in the Norfolk Farm era in A Chronicle of Ancient Sunlight. Her daughter, Georgina, was educated at Summerhill, the very progressive school (especially then) run by A. S. Neill at Leiston in Suffolk. HW’s eldest son, Bill, maintained a close friendship with Georgina throughout his life. (She, as did Bill, lived on the North American continent, but seems to have maintained family property in Norfolk.)

*************************

There is very little background information about the writing of The Children of Shallowford.

|

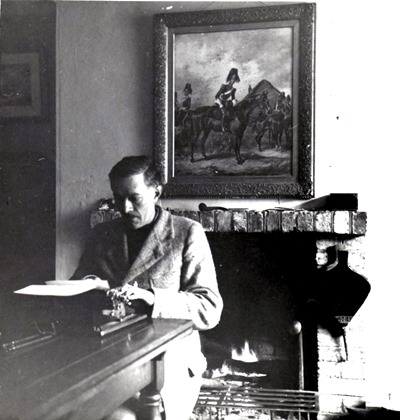

| HW at work at Shallowford |

In mid-May 1937 HW, together with his brother-in-law Robin Hibbert (called back from Australia to help on the farm) moved up to Norfolk, camping for the first few months; from that time on both were totally immersed in the massive preparations necessary for the subsequent ownership and farming of ‘The Norfolk Farm’ – Old Hall Farm at Stiffkey, on the North Norfolk coast. Diary entries tend to be almost totally to do with farm affairs.

It is clear, however, that this book had actually had a long genesis. The first mention of the project occurred on 11 May 1934, when HW was on board the SS Montcalm returning from his 3-month visit to Georgia, USA, and recovering from his disappointment over the rejection of The Sun in the Sands, and his sea-sickness:

Yesterday I wrote notes for short stories & children’s book, Tales told by my Children, or Stories for my Children.

It was nearly a year later before the next mention appears: on 12 April 1935 (one of very few entries, for HW was working hard on writing Salar the Salmon) he recorded:

Another enthusiastic letter from Weeks reinforced by one from Sedgwick, editor of Atlantic Monthly. They are keen on Tales of My Children.

Edward Weeks was a director of the American publishing company Atlantic Monthly Press (whose book publishing company was Little, Brown & Co.), while Ellery Sedgwick was editor of its prestigious journal Atlantic Monthly. This magazine had been printing HW’s essays occasionally since August 1927 (the first one was the iconic ‘The Crowstarver’, a memory of those childhood visits to stay with his cousins at Aspley Guise in Bedfordshire).

HW’s diary note refers to a letter he had received from Ellery Sedgwick, dated 29 March 1935, showing that HW had been in contact with a new project; it states that Sedgwick had received ‘your little essay “Tales of my children”’. Sedgwick wrote that he would be glad to print the first chapter, and indeed, to make a little series of such pieces. He will also discuss the book with Weeks, which he obviously had, as HW’s diary note refers to a letter from Weeks.

In a letter to Weeks, dated 18 April 1935, HW wrote (a copy is in his archive files) that he was working hard on ‘Salar the Leaper’:

Therefore I feel I can’t give much time now to TALES OF MY CHILDREN. If the Editor has already begun to print the first chunk I sent, then I will write a few instalments. It will be easy. But at present things do seem rather too much for an overworked brain. . . . [re fifth child on the way; then complains about Cape as publisher] . . . Faber seems an easier air to breathe.

Yes, Tales of my Children will be good and readable. I perceive the way to move and interest people in the classical manner; as opposed to the romantic or sentimental. . . .

Weeks’ reply, by cable, 9 May 1935, was: ‘Let nothing interfere with Salar. . . .’

HW did concentrate on Salar, but a few days after this he had to cope with the blow of T. E. Lawrence’s accident and subsequent death. (HW’s writings on TEL will form a separate section in due course.)

(For the full background to this most interesting American connection see Atlantic Tales: Contributions to The Atlantic Monthly, 1927-1947, ed. John Gregory (HWS, 2007; e-book 2013) which includes a detailed explanatory Afterword: ‘Both Sides of the Water’ by AW.)

On 8 May 1935 HW had already noted: ‘Rec’d £20 from Atlantic Monthly for first instalment of Children.’

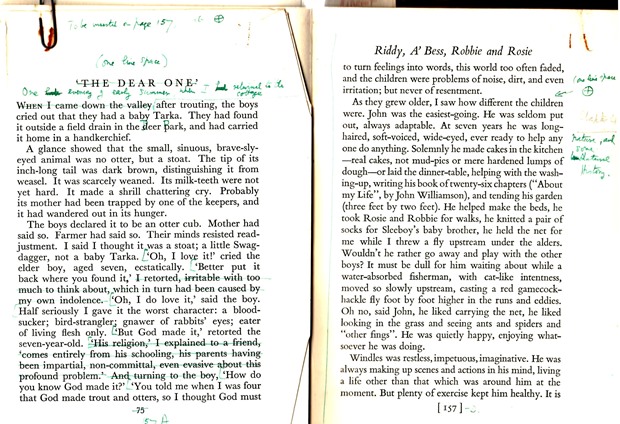

The story appeared as ‘The Dear One’ in the May 1935 edition of Atlantic Monthly (and can be found in Atlantic Tales). It tells the tale of an injured baby stoat that the children had found in the Deer Park, how they tried to look after it and its subsequent death. A charming and very moral little tale of the test of faith and the fairness or unfairness of life in the reaction of a young boy: the said boy being Bill (known as Windles) then aged seven. The story had first appeared as a Sunday Referee article, No. 2, 28 May 1933, and subsequently appeared in The Linhay on the Downs (Cape, 1934). It was not included in the original Children of Shallowford, but HW pinned a copy cut from Linhay on the Downs in the file copy of Children of Shallowford that he used when preparing the 1959 revised edition (see revised edition p. 69-72).

As indicated in HW’s letter above, no further ‘Children’ instalments appeared in the Atlantic Monthly for some time. The next HW contributions were a 3-part abridgement of Salar the Salmon, published that autumn in England and by Little, Brown & Co. in the US in June 1936. Then in December 1939 Atlantic Monthly printed episodes directly lifted from the actual Children of Shallowford, seemingly as an advertisement for their own edition of the book, although this never materialised.

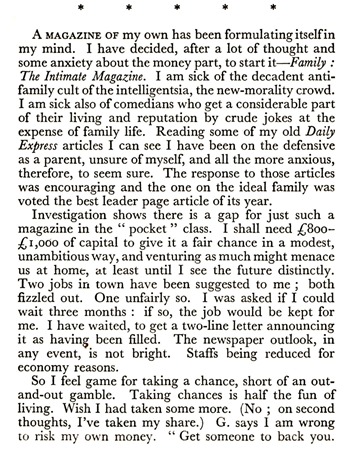

However, HW had another outlet for those preliminary ‘Children’ essays. He had been asked by his friend Reginald (Reggie) Pound for a contribution to help launch his new magazine Family. Reginald Pound (1894-1991) was a very well-known journalist and writer, though Reggie himself seems to have thought that his main claim to fame was the fact that he had fathered seven children! As I noted in my HW biography, Henry Williamson: Tarka and the Last Romantic (1995), although they were friends and a small file of letters exists from Reggie, there is only one mention of him within HW’s personal archive – in 1942, when HW went down to London after a bout of illness and mentions, in passing, seeing Reggie at the Savage Club.

However RP (his letters tend to be signed thus) mentions HW several times in his anecdotal autobiographical books, Their Moods and Mine (Chapman & Hall, 1937) and Pound Notes (Chapman & Hall, 1940). While these have no relevance to the immediate subject here, they shed an interesting insight on HW, giving a clear indication of HW’s intensity of character. They can be found as an appended page to this entry, Henry Williamson and Reginald Pound. The books are very well worth reading in full for their portrayal of contemporary literary and social society (second hand copies are relatively easy to come by).

Importantly, though, regarding the immediate subject of Family, the little magazine that he founded, Reggie gives the following information:

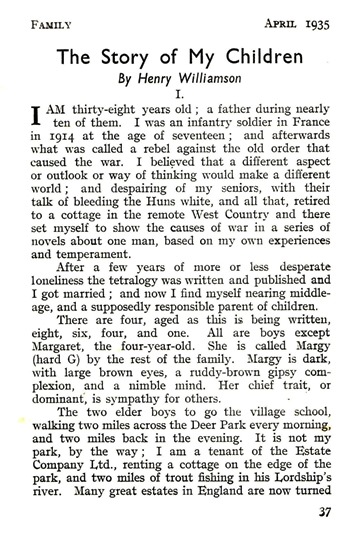

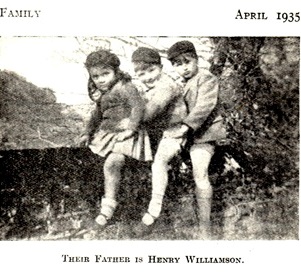

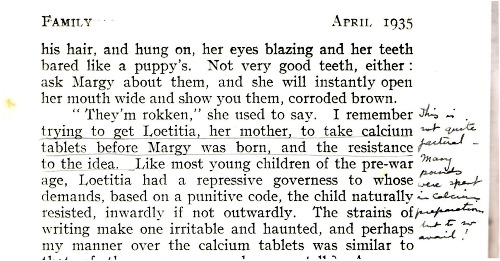

HW contribution to the first issue, Vol. I, No. 1, April 1935 (‘Founded and Edited by Reginald Pound, 12s. a year, Post Free’) was ‘The Story of My Children’. As already stated in the extract from Reggie’s own book, the list of contributors was interesting.

|

| Margy (hard G), John and Windles |

Note Loetitia's wry comment on HW's version of events:

HW sent five extracts altogether: Vol. I, No. 2, May 1935, had two pieces (not noted in the Content’s List but was on the cover list); Vol. I, No. 3, June 1935; and Vol. I, No. 4, July 1935. There is a copy of the September issue present but nothing further. Despite the fact that the first issue sold 1400, lack of capital was always a problem for Reggie, who had to spend a great deal of time and effort finding advertisements to offset production costs; the magazine did not survive beyond a few issues (possibly a year).

Rather frighteningly (in light our current awareness), in those more innocent times there is a section at the back of this magazine headed ‘Junior Who’s Who’, giving mini-biographies of children, many under 5 years of age and all under 16, with their interests and comments: one issue includes the Princesses Elizabeth and Margaret, with an article in the text. Many of the children are of aristocratic origin. All of A. P. Herbert’s children appear, for example, but not those of HW (no doubt saving his material for his book).

So there was quite a flurry of activity in 1935, at a time when HW was pushed to his limits anyway with the intense writing of Salar the Salmon. There is nothing further until a brief diary entry on:

Monday 17 October 1938: This night I began the children’s book, properly.

18 October: Working hard at book.

19 October: Book degenerates into autobiography.

Indeed, that is a prominent feature of the finished book and a very honest view of himself in relation to his family. It also gives us his ideas on education more clearly than in his early books, where he put his ideas in a rather abstract form. These aspects give this book an interest far beyond its amusing account of childhood behaviour.

The next mention comes on Thursday 12 January 1939: ‘I am rewriting Tales of my Children.’ Then on 5 May 1939 HW motored to London, taking his son John to the London Westminster Choir School (Brixton) and recording on 10 May:

I sold my new book The Children of Shallowford to Faber for £200 advance, 20% royalty. Also fixed up series of articles in Evening Standard, 3 months, at £40 a month.

(The Evening Standard articles have been collected in Heart of England: Contributions to the Evening Standard 1939-1941, ed. John Gregory, HWS, 2003; e-book 2013.)

There is no further mention of the book whatsoever and no indication of publication. HW was heavily immersed in the work of the farm. He had no time or energy to spare. So there is no exact date of publication: the book itself had the date ‘October’; Matthews states ‘September’.

HW was in London on Friday 1 September, and learned that Warsaw had been bombed, his diary recording: ‘I went into Evening Standard office & watched the news coming in.’ War was declared on 3 September, after the invasion of Poland by Germany. HW recorded: ‘Today at 11 am Gt. Britain declared war on Germany.’ Both HW and his readers had other more weighty matters on their minds than the book about his children. For most September and early October HW was blasting chalk from the quarry to spread on the farm fields: a total of 1010 tons over 3 weeks.

*************************

The Children of Shallowford is a straightforward and charmingly honest story of the young Williamson family’s life at Shallowford, the family home beside the River Bray on the estate of Lord Fortescue at Castle Hill, Filleigh (near South Molton, North Devon). But the first edition opens much earlier than that, with the birth of the first child in 1926 when HW and his wife, here given her formal name of Loetitia, were still living at Vale House in Georgeham.

As the children are brought up in the freedom of the countryside, we learn of their everyday affairs and sayings as they played and quarrelled and roamed wild, giving a faithfully true picture of their childhood.

However, the book is also highly autobiographical and so we learn a great deal about HW himself.

The revised edition concentrates more on the lives of the children. HW’s file copy, marked up in 1959, shows that he omitted personal biographical material for use in the Chronicle of Ancient Sunlight series, which he was by then well into. I will show the major changes within the text that follows.

A brief diary note on 11 March 1959 shows HW was correcting proofs for the new edition:

It looks good to me. Faber’s catalogue gives pride of place to Richard’s Dawn in their catalogue under the Autobiography sub-heading. I come next. Most satisfactory.

(His son Richard’s first book The Dawn is My Brother was published at this time. By a strange coincidence the HWS have just reprinted it as an e-book.)

It is worth looking at The Children of Shallowford book chapter by chapter for clarity, and in some detail as it contains several interesting passages.

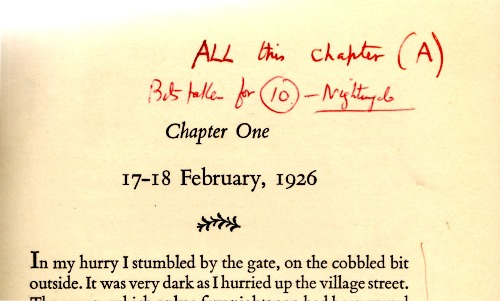

Chapter 1: 17-18 February 1926 (not used in 1959 revised edition)

We are told the story of HW’s anxious and confused emotional actions as his first child is born. Going to fetch ‘Dr. Shardeloes-Lane’ (Dr Elliston-Wright, also a noted naturalist, who lived in Braunton, and friend as well as doctor), HW finds him playing skittles in the pub and in no hurry to leave, while the midwife in Crosstrees (Braunton) had already dismissed the symptoms as a false alarm. HW becomes increasingly agitated! Here he gives a quite detailed description of Vale House in Georgeham where HW and wife were currently living.

|

| Loetitia, Windles and HW at Vale House |

HW has arranged with a near neighbour and friend, Valentine (Aubrey Lamplugh, whose elderly parents actually owned Vale House and so were HW’s landlords) to have the use of their Trojan car to take Loetitia to the nursing home. The tale of this arrangement is quite hilarious, involving first bathing their own young daughter – Lois Lamplugh, who grew up to become an author herself, including a memoir about HW, A Shadowed Man (Exmoor Press, 1991) – bursting beer bottles in the heat of the fire, and several alarums as the ancient car negotiates the road to Braunton (only a couple of miles or so away!).

HW inserts here some interesting points about his own original ideas and ideals. Having been a fearful and unhappy child:

Later, after the Great War, I rejected violently all those circumstances and ideas which had made me fearful, mentally perplexed, and unhappy. I saw in those things the true origins of the Great War. This was the theme of my writing when I went to live alone in Devon. . . . There must never be another Great War. There would be, unless the survivors of my generation altered their minds. . . .

I believed that goodness was natural in man, if only man was permitted to be natural. I would reveal this to the world through my books . . . Education needed to be fundamentally altered. . . . I saw God in the true, natural, fearless minds of children properly grown to men and women.

[I realised] Communism was not the way I desired . . . I wanted a national regeneration of all classes, with natural leaders of a classless state. . . . My book would be that [deciding] factor. . . .

Tomorrow I would start again and finish the book, which cried on me at night to be finished, so that the dead of the War could be at peace. Sometimes it seemed the dead were watching me steadfastly, less the truth of our generation be lost. I was dead with them, comrade of the World War, and they lived in me again.

The book being referred to here is The Pathway (Cape 1928), containing what HW referred to as his ‘Policy of Reconstruction’. The book is a magnificent story but the ‘Policy’ is so nebulous as to be virtually non-existent.

Chapter 2: Confusion of Feeling (not used in 1959 edition)

He wakes the next morning ‘knowing’ he is a father but:

my elation gradually left me, and I began to feel doubt, then the stirring of fear. Perhaps Loetitia was dead? . . .

Readers will know HW used this scene and feelings, taken to their most fatal extreme, for the death of Barley, the first (and totally fictional) wife of Phillip Maddison, in It was the Nightingale (vol. 11, A Chronicle of Ancient Sunlight, 1962) and to some extent with Phillip’s second wife, Lucy (Loetitia herself). All is well of course but:

I looked at them, and saw how completely mother and child were one, and upon me grew a feeling of aloneness, and a desire to fade away into the world of my book . . .

That feeling was to increase as HW realised that he no longer had the full and first attention of his wife. It was something he could not cope with.

Chapter 3: The Simple Life Becomes Complicated (not used in 1959 edition)

HW makes the decision to recast his otter book. But when wife and baby come home the baby does not thrive. However, he is christened: ‘My uncle, a retired sailor and a bachelor, was baby’s godfather.’ This is Henry Joseph Williamson, born in 1872, so 54 at this point, an ex-purser, who lived in Bournemouth. We note that Henry Joseph is as dictatorial as is his fictional counterpart (Hilary Maddison) in the Chronicle of Ancient Sunlight.

Loetitia gets cystitis and the baby becomes even more fractious. HW relates how he wrote his otter book while nursing the baby. (Loetitia was somewhat sceptical about this notion! ‘Possibly one night dear,’ was her comment.)

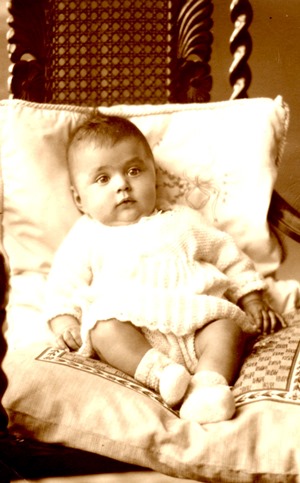

|

| Windles |

HW goes to see ‘Granny’, taking the baby in the sidecar of the motorbike: ‘Grannie’ Hibbert, Loetitia’s grandmother, wife of Col. Hugh Hibbert (of Birtles Hall, Cheshire), deceased, currently ‘living in a cottage outside the high walled gardens of her old home’. She has featured in previous entries of ‘A Life’s Work’ but as a reminder, Grannie had lived at the sumptuous Broadgate House at Pilton on the north-west side of Barnstaple. The house had once belonged to her father, Frederick Lee, a well-known Royal Academy artist. One of Grannie’s sons had got so deeply into debt that she had had to sell the house to help him. (Although, being quite elderly, a small cottage was probably more suitable!) Grannie offers her old nurse (and that of Loetitia’s mother in her long illness): this is a disaster – but becomes grist for the Chronicle mill in due course. (I personally cannot quite believe this story – she is so dreadfully inefficient and dirty – not what one would have expected of ‘Grannie’s’ nurse at all!)

Chapter 4: Son and Mother (1959 edition: Chapter 1)

HW finds himself lonely and increasingly irritable. But he gives a detailed and loving description of the activities of Baby Windles: first steps, first words, But:

Only ten years ago – the day before yesterday – I was in the Ancre valley, and the night sky was dilating and quivering with the immense crash of barrage fire.

|

| Windles aged 2; Vale House is on the left |

Chapter 5: 'The Flax of Dream' (not used in 1959 edition)

That thought is continued with some details of the film The Somme, HW being upset by the attitude of the children watching it. It determines him to finish his book. This leads to a description of his experience of 1915 when he was hospitalised and sent back to England, and his fears about having to return to the Front; but above all, the dawning realisation, arising from his experience of the Christmas Day Truce, that ‘the War was a terrible misunderstanding’.

He also notes here (in a book that he is actually writing in spring 1939, so telling his readers his immediate pre-Second World War thoughts), that one of the battalions taking part in that Christmas Truce was the List regiment from Bavaria, ‘in which served an Austrian volunteer named Adolf Hitler’. HW was convinced that such a man, who had been in that war and shared that amazing experience, could only, and would only, think as he himself did: never again must there be another war.

He then reads (and so quotes) a long passage from Richard Jefferies’ The Story of my Heart: a philosophical message basically stating that we should all strive to do something towards the common good of mankind every day. It is obvious that he associates this ideal with the current German regime – and it bears out what he was told and shown (and believed) on his 1935 visit.

His own part in this ideal world – this Utopia – is to finish his book: so he begins, and continues nonstop for best part of two days. Then, ‘after a month of hard continuous writing, the book was finished.’ That was The Pathway: HW noted in a letter to T. E. Lawrence dated 1 May 1928 that he had finished The Pathway the previous week.

Chapter 6: 29 October, 1928 (not used in 1959 edition)

The following October HW & wife decided to walk to Barum (Barnstaple), the nearby market town, (that’s quite a longish walk for someone about to give birth!) to make arrangements for the birth of their second child at the nursing home there, but Loetitia is in some discomfort ‘from eating rhubarb’, so he leaves her there. John was born on that day, the same day that The Pathway was published (note: this was actually on 28 October 1928!). That night HW reads the whole of his book to Valentine (Aubrey Lamplugh) and friends – to great emotional success. But HW tells us that he and Valentine then parted ways. (There are several quite scathing notes about Aubrey Lamplugh within HW’s archive: he decided, or discovered, that there was some considerable discrepancy in Lamplugh’s claim to army service. This should be researched for accuracy.)

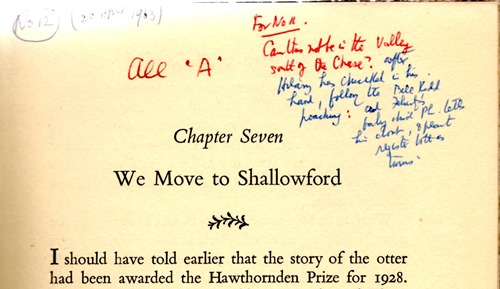

Chapter 7: We Move to Shallowford (not used in 1959 edition)

We are told, as a recoup, about the prize for the otter book. Then Uncle Henry Joseph attends Baby John’s christening, and we learn a little more about his life; that his wife had run off with a younger man during the War (an episode which is fictionalised in the Chronicle. This is something I have never checked on.) His second fictional marriage to Barley’s mother is of course totally made up!

Living in Georgeham becomes an increasing problem and they decide to move. HW tells us his dentist told him about a suitable cottage to let: the cottage known as Shallowford:

It was a long white house. Pear trees grew against the south walls, with hollyhocks and sunflowers. It had paths of yellow stone chips and two small lawns, in each lawn a yew tree.

|

|

The photograph of Shallowford that formed the frontispiece to the first edition, taken in the early 1900s |

HW then relates the problem of the hearth and chimney smoking, and his special design to stop this – and his horror when he returned from a visit to London to find the original worn blue slate hearth slab had (against his express wish) been removed and replaced by concrete.

Chapter 8: Enter Coneybeare (not used in 1959 edition)

We read the story of Coneybeare’s life: real name Cecil Bacon, one time factotum to the parson in Georgeham, and sacked due to his drunken ways. HW had taken him on out of pity for an old soldier. (He also features in the Chronicle of Ancient Sunlight as ‘Rippingall’.) The tale of his carrying-on is quite hilarious – and true! There is even a ‘document’ proving that HW did actually make him sign his wages into a sort of trust fund for use in his own old age.

But sadly we learn:

After a while I found Loetitia and I were not sitting any more before our fine new hearth. I sat alone, writing or trying to write. Loetitia sat by the nursery fire . . .

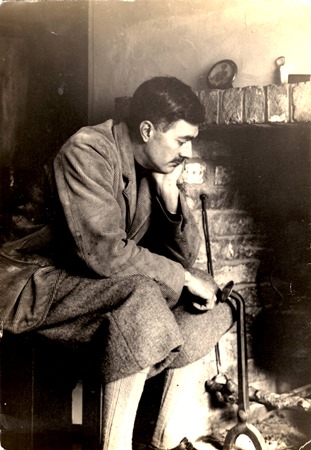

|

| A pensive HW by the hearth |

Chapter 9: 15 April 1930 (not used in 1959 edition)

The problem of hot water (mostly lack of) for washing and the shortcomings of staff (Coneybeare): all were symptoms whose root cause, HW believed, was also the cause of the Great War. And here HW introduces a singular phrase based on the well-known collect from St Paul’s Epistle: a concept he was to use more than once in future books:

The greatest virtue in a world of distressing need was charity. If all men had a clarity there would be no need for charity.

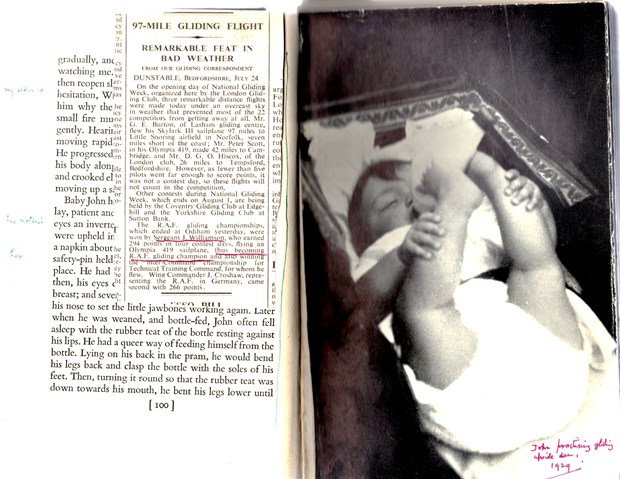

How this relates to fire-making has just to be accepted! But making up fires – here carefully prepared by banking up the night before – was an obsession with HW. The fire leads to Baby John and his unusual way of taking his bottle.

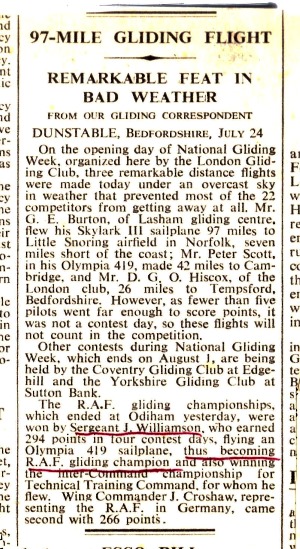

The cuttingabove, pasted into HW's file copy, is enlarged below:

On the back of the original photo HW wrote in 1959:

Sergeant John Williamson, R.A.F., practicing gliding in his pram in North Devon

We read of the differences between the two boys: Windles intense; John serene and without fear, but also very mischievous. We are given examples of this, including watering with dirty water the basket of clean linen freshly delivered by the laundry man!

Then once again HW and Loetitia set out on a walk from Georgeham to Baggy Point. And once again Loetitia is taken to the nursing home as she is having pains: half an hour later a baby girl is born!

She had dark eyes, and much dark hair, like a Japanese doll, on her head.

|

|

Margaret, born 15 April 1930, in her pram |

Chapter 10: Exit Coneybeare (not used in 1959 edition)

Coneybeare does not follow HW’s household rules about cleanliness and tidiness. But in his turn he is upset by HW becoming a vegetarian at this time. However a party is held to celebrate the publication of the revised Dandelion Days. (The new edition was published in early March 1930 – BUT the author is described as wearing ‘a red Canadian Hunting shirt and Greenwich Village corduroy trousers’, which can only have been post-March 1931!) From its description it was a very good party! The wine flowed liberally, especially into Coneybeare, dressed point-device in evening dress. At dawn HW tells him:

‘Coneybeare, you were magnificent to-night. Thank you.’

In the morning Coneybeare has left: ‘The artist dreads anticlimax . . . We never saw Coneybeare again.’ (It wasn’t quite that straight-forward, as you can read in my HW biography, Henry Williamson: Tarka and the Last Romantic.)

Chapter 11: On Dream, Irritability and Death (1959 edition, Chapter 2, same title)

This chapter relates the poignant story of John’s illness, aged two, from pneumonia and pleurisy which progressed seemingly to the point of death, and ending with a burst ear-drum. The child cried for its father: and HW was convinced that his own will-power flowed into his son, saving his life. He does however admit that it was really Loetitia’s patient and continuous care that really kept the child going until the crisis was passed.

Chapter 12: The Way of Life (1959 edition, becomes part of Chapter 3, title as next chapter)

There is a lovely description of feeding the tame trout in the pool below the Deer Park bridge: Humpy Bridge, and of how Windles would not go with his father, thinking he preferred John, and how his father overcame this jealousy and fears with his tale of ‘Cold Pudd’, the magic elf, who lived in an oak tree and was very fond of cold Christmas pudding. (The Cold Pudd story has been handed down to grandchildren and great-grandchildren – always a favourite!)

Chapter 13: Cold Pudding becomes the family friend (1959 edition, Chapter 3, title as here)

Continuing the story of Cold Pudd, but now through the children and their wanderings – Margy only being two at the time! Their mother was totally unconcerned. But to Father’s horror he discovers a favourite place of theirs was the railway viaduct overlooking the Deer Park Valley. Father invokes the anger of Cold Pudd to stop this happening again. Windles understands!

Chapter 14: Galloping Annie’s Terrier (1959 edition, Chapter 4, ‘On Terriers, Ghosts, Trout, and Sport’)

A tale involving Annie Rawle, who came to work for them on the death of her previous employer, the eccentric sportsman Arthur Heinemann, breeder of the famous Jack Russell terriers. (Both have featured in previous entries in ‘A Life’s Work’.) This is intertwined with a story about Margy’s ‘ghose’: thought to be a ghost, it was actually a mouse which visited her cot because she had biscuit crumbs!

HW had bought a terrier pup from Annie Rawle: ‘The dog grew up very spirited, entirely without fear.’ The dog gets accused of killing their neighbour’s chickens, an expensive business (this has also featured in an earlier entry and is verified by diary entries), for which it is punished.

HW, working hard on Salar the Salmon, was in that state of nervous tension that was inevitable from the effort involved. The final straw occurs when the terrier kills a cockerel and the children drop and break a cream bowl making a mess on the floor. Margy also wees on the floor. HW catches them all playing, as he thinks, with this horrendous mess, sliding about on the floor. Losing his temper he takes off his braces and hits the children and then thrashes the dog. Immediately of course he is full of anguish at his action: he gets the children to hit him with the braces – and all is well.

HW then learns, with some amazement, that Margy goes to Sunday School. When asked why, she says there is to be a treat. However, she does also wonder about the ‘boss of the world’. But:

After the treat, Margy went no more to Sunday School.

|

| Windles, Margy and John sitting on hearth fender at Shallowford |

HW added an MS note on p. 146 for revision – see 1959 edition, p. 72:

Chapter 15: Riddy, A’ Bess, Robbie and Rosie (1959 edition, mostly Chapter 6, ‘We Go Travelling’)

‘Riddy’ is Mrs Ridd, who replaced ‘Galloping Annie’ (Annie Rawle, so named due to her hunting activities). ‘A’ Bess’ is Ann Thomas, with daughter Rosemary born a week after Robert in September 1933 (and so known as ‘the Twins’). Mrs Ridd was cheerful and open to all HW’s ideas on cleanliness and tidiness, so HW was (temporarily) much happier on the domestic front.

We are told that Robert was not thriving, while Rosemary did. In exasperation HW writes that he suggested that the solution was that Ann should feed him with her own obviously excellent milk. Thereafter Robert thrived.

|

| Robert and Ann |

I asked both mothers about this: both laughed and said it was totally untrue! Ann cannot be placed at Shallowford during those crucial early months of breastfeeding anyway – and Baby Robert looks as chubby (if not chubbier) as his siblings! (Loetitia did actually have difficulty in breast-feeding all of her children.) It was obviously a thought that had occurred to HW and so it became real to him – or he just thought it made a good story.

The story turns to the river Bray and its stock of fish and the happy summer sun. Even so the sun is not allowed to engender total happiness:

From the gazeless orb of brilliance energy poured down: magnificent to the earth, but a mere dwarf-yellow star of diminishing magnitude in stellar space. It was burning out.

Likewise the human mind, concentrated on one line of thought, was diminishing in energy and light.

[BUT:] Never shall I forget that bright, clear water, into which I gazed from bridge and tree and bankside, so many thousands of times.

So the chapter continues with the stocking of water with Loch Leven brown trout, giving their life history, as HW and the children watched over them in their

strange life of the river – the beautiful, limpid, shadow-dreaming Bray – the stream which would be flowing a thousand centuries after we were all forgotten.

It is a lovely lyrical passage: HW at his best. The angst that mars Goodbye West Country towards the end has vanished. Now that he is away HW can recollect in tranquillity:

feeling myself and the children part of the great stream of life, and deeply content for the gift of being alive in the world.

The children’s different characters are given in acute and accurate thumbnail sketches, but done with kindness and understanding: altogether a delightful chapter.

Chapter 16: Life is Sometimes Fun (1959 edition, Chapters 5 and 6)

HW’s attention turns to Margaret (born 15 April 1930), as Loetitia tells him the older boys tease her (I’m afraid that actually she rather asked for it!).

|

| Margy and John on the bank of the River Bray in full spate |

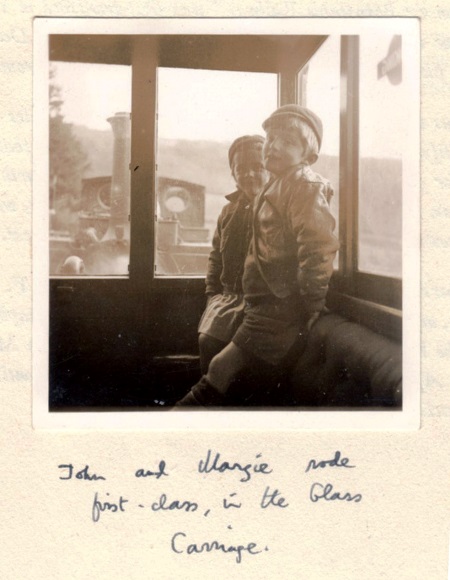

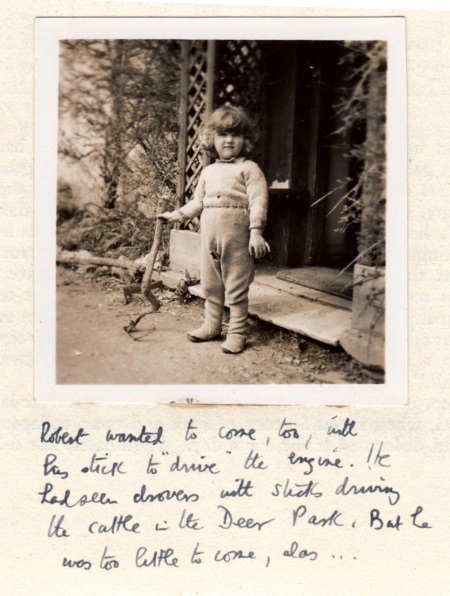

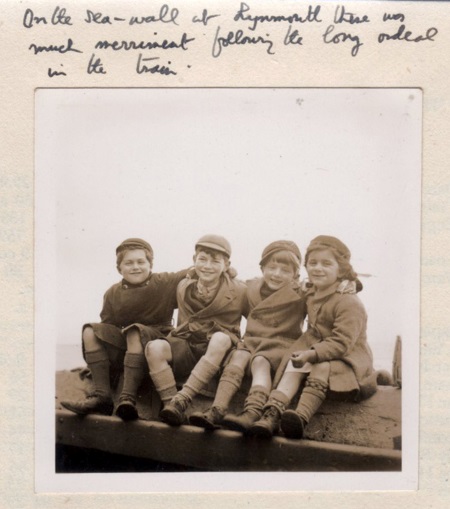

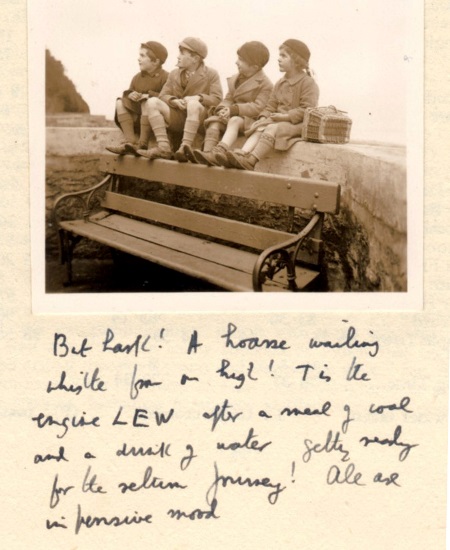

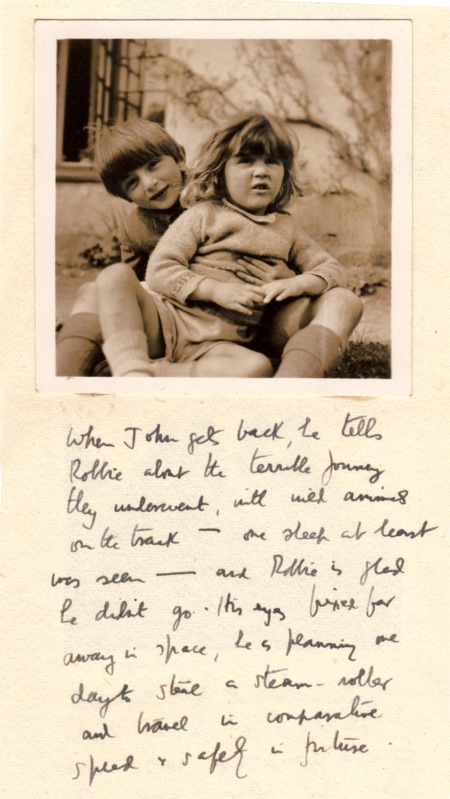

We now read of two happy expeditions: one to the beach, where a cargo of oranges is found, providing a morning’s grand sport. The other is a trip on the iconic miniature railway from Barnstaple to Lynton. It was a delightful expedition and is a ‘must read’ passage.

In the Literary Archive are several copies of L. T. Catchpole's The Lynton and Barnstaple Railway: an early edition (it was first published in 1936) and two copies of the 1949 fourth edition. This is the delightful frontispiece to the book:

Into one of the 1949 copies HW at some point pasted on to the blank spaces spread through the book photographs of this adventure to Lynton, made nearly fifteen years earlier, with an amusing linking commentary (the boy next to Windles is his friend 'Sleeboy', John Slee):

The chapter ends with an amusing incident: the children happily swimming naked in the Bray on a hot summer afternoon panic because they get wet in a sudden rainstorm! Such is the logic of children!

Chapter 17: The Hut on the Hilltop (1959 edition, second part of Chapter 7, ‘The Beacon on Ox’s Cross’)

The chapter opens with a résumé of how HW wrote Tarka the Otter, and organised sales of its limited edition while learning that ‘a two acre field on the hill above the village’ was for sale at £125. His share of the limited edition of 100 copies would pay for it so he wrote a cheque for £25, all he currently had – the rest to follow later. But it was the news that he had won the Hawthornden Prize (£100) which gave him the remaining capital and made his Field safe. It didn’t happen quite like that. A letter from his mother reveals that she actually originally secured the Field on his behalf before Tarka was published. However, the overall gist of this is correct.

We learn of the planting of trees at ‘Down Close’ as the area was called (enclosed downland), though it seems to have reverted to ‘The Field’ from the start. ‘Down Close’ was evidently a little pretentious for HW and the little Writing Hut he was to build there. There are several typescript and manuscript pages, heavily corrected, in the archive that describe the purchase of the field and the building of the hut, which are reproduced on a separate page.

We also read about skiing down from the Field to the village below after a sudden fall of snow. HW had first gone on a skiing holiday in January 1929 to the Pyrenees with his friend Kit Williams: so although the date here would seem to be 1928, for HW to have skis must make it at least 1929. He also skied in New Hampshire in February 1931, on the visit when he delivered his lecture on Hamlet to Dartmouth College, and then Yale and Harvard.

|

|

HW in the Georgeham area (photograph courtesy of R. Knight) |

HW then tells us briefly about the Hut that he built in the south-west corner of his field:

behind the thick cover of leaves and branches, and made a brick open hearth across one corner, and a small space over for a ledge to hold a mattress and blankets.

And then in great detail about how he had to repair it:

One summer when Loetitia was in the nursing home, I took Windles to live in the hut. Windles was nine . . .

So: Baby Richard was born in the Ebberley Nursing Home in Barnstaple on 1 August 1935, and Windles would indeed have then been nine. HW had just finished the intense bout of finishing the writing Salar in his Hut at the Field at Ox’s Cross and was dealing with proofs. He was exhausted. A letter to Jonathon Cape regarding Salar, in reply to his of 13 August 1935 (giving us an exact date), ends:

Hut stripped and I’m carpentering and working all day before the rain comes.

It is difficult to see how Windles could have ‘lived in the Hut’ (but possibly in the ‘Loft’ over the garage/workshop), but we learn here that the other children were lodging with ‘a friend who ran a vegetarian guest house’ in Georgeham village (the famous/notorious Miss Johnson, a naturist), so possibly Windles also had that refuge, and just walked up the hill each day. It is interesting to have this 1935 hiatus fleshed out with this family detail.

The chapter ends with HW needing to be cleaned from the bitumen mix he has used to protect the Hut materials from rotting; he uses paraffin and needs instant sluicing down with water by his children: ‘Old Tar Baby’ running wild naked with his excited children.

Chapter 18: The Beacon on Ox’s Cross (1959 edition, first part of Chapter 7 under same title)

‘It was the time of King George V’s Jubilee’: 25 years – 6 May 1935; born in 1865, the King was 70 years old. (Note HW has gone back a few months from the previous chapter: his time scale is always fairly loose and sometimes downright slippery!)

It is a lovely passage describing the local celebrations at Filleigh (the Stag’s Head is the local pub) and their own private celebration with a bonfire at the Field.

|

|

The 1939 edition captions this: 'Jubilee party' In the front seat of John Heygate's MG is Margy; in the back are Windles, 'Sleeboy' (John Slee), ? Annie Rawle's daughter, and John. Photograph taken in 1936 in the track leading to Shallowford cottage. In the background is the gate to the Deer Park (Humpy Bridge can just be made out). The building top right was demolished in the 1960s. |

We climbed up St. Brannock’s Hill, then up the steeper Noman’s Hill, and along the high ground to Ham village. We passed the beflagged church tower, and climbed again to Windwhistle Cross, and the field. . . . Windles switched on the radio [they had brought a portable with them]: soon the King’s voice, grave and slow, was speaking to us from the air. He sounded exhausted. He had been ill with pleurisy. I could not help my eyes filling with tears. I remembered him in France in 1914. Nothing seemed to have happened in the world since that time – and now he was old and tired.

[Eventually they light their bonfire:] Flames ran up beside one of the oak poles and the wind pressed it to bright anger and soon we were standing in what seemed a great heat and light. Moving to one side we saw in the darkness below many red specks of fire extending away to points scarcely seen.

Windles counted twenty-seven beacons.

|

|

The 1978 edition captions this: 'On spread-out Great War army blankets, the children await dusk and the Jubilee beacon' |

The event got a rare entry in HW’s diary:

H.M. George 5’ths Jubilee, also 10 years ago I was married. Children, less Robert and Rosemary, and I with Gipsy & A.T. motored to field with flag-flying trailer and made bonfire of furze & other hedge trimmings. Fireworks. We had eggs & bacon in the loft & saw at 10pm 27 beacons breaking into small red points of flame in the darkness below & around us. . . .

But he became irritable about making up the beds in the ‘loft’ as he was expecting the Renshaws to come over from Instow (unlikely – there would have been a ‘superior’ local celebration). The ‘loft’ room was a bare board space above his old garage/workshop erected by the top main entrance to the field and reached by a vertical ladder up the far wall: today a smart chalet! However:

We enjoyed it all & I was glad not to have spoiled the poor dears holiday.

The book tells us that the plan for the next day was to go to the beach. HW’s diary bears this out:

We all went to Vention Sands & had picnic, rather fun. Ann & I bathed, 30 seconds immersion only. Cold east wind. We found many nests in my hilltop trees. Chaffinch, hedgesparrow, thrush, etc. A small sanctuary.

He was of course in the throes of writing Salar at this time, and was also involved with sorting out his plans on the work of his recently dead friend Victor Yeates. He planned to visit T. E. Lawrence on his way to London to discuss this, but exactly a week later Lawrence had his motorcycle accident, dying a few days later.

Chapter 19: Winds of Heaven (1959 edition, Chapter 8, same title)

The stream that ran down our valley began its life in the bogs of Exmoor. Northwards the high ground was the home of winds.

So HW moves into a typical lyrical description of Exmoor: then the ‘diamond-hard’ winter wind in the Deer Park, and the warm wind from the Atlantic – out with the children, they pretend to be birds flying. But Father has to write, as:

There was another baby in our house now. He was a crawler, called Richard Calvert Leopold.

|

| Loetitia and baby Richard |

The time is now spring 1936. The older boys play with their railway set; Robert, and so also Rosie, treat the area as a sea on which to sail boats, Baby Richard has a one-wheeled omnibus. This strikes me as very interesting: in adult life Bill’s hobby was trains and their horns, Robert’s is boats and sailing, Richard’s is vintage cars. John’s future gliding exploits are not visible here but, as previously stated, HW noted it on the photograph of John lying in his pram holding his bottle with his feet.

That game ends, inevitably, with a squabble. To restore peace ‘Father’ takes the older children for a walk in the Deer Park: more wind.

Then Baby Richard takes his first real walk – on his own and unseen – on the day of the ‘Great Gale’:

the day on which thirteen great trees were overthrown in the Deer Park.

(Shades of W. H. Hudson there, and the corresponding echoes of the opening of Tarka the Otter.)

It is realised suddenly that Baby Richard is missing. All search. When he is eventually found he is sitting beside a newly-uprooted beech-tree in the Deer Park, clutching a daffodil in each fist ‘while the gale roared round him. And he was happy.’ The child was indeed the father of the man! A hot bath to warm him up, into which all the children clamber to celebrate!

Chapter 20: River in Flood (1959 edition, Chapter 9, ‘Freshet’, & Chapter 10, ‘John shows a Cool Head’)

Autumn 1936: ‘we spent much time by the river’. (HW would have been at that time very aware that the time of Shallowford life was coming to its end.) He had made it very clear to the children what to do if one of the young ones fell into the fast-running spate water. Wait until they get into a back eddy and then pull them out. (This advice can be seen to have its own flaws!) They go for a walk to the Stag’s Head Weir (see end-paper map to Salar the Salmon) and watch the fish. Another week, more rain, another walk: the salmon are running the weir and to help them through, HW, with difficulty, pulls open the fish pass. (Note the similarity to a scene in Salar.)

‘Father’ goes off to London and while away ‘something happened’ that he didn’t know about until he read it in John’s book ‘About My Life’ (printed here as chapter 24). John decided to take Robbie and Rosemary for a walk to Stag’s Head Weir: he being seven, the twins two and a half. This places the event in late winter 1936, John becoming seven in October 1935. In John’s book as printed here, John states it happened in January.

|

|

John with Rosemary (left) and Robbie (right) in the garden. John always looked after the younger ones. |

HW describes the scene in great detail (remember he wasn’t actually there!) but he does ask the reader to compare his ‘multi-detailed prose’ with the ‘laconic calm’ of John’s account. Robbie falls into the water crossing a plank bridge and is in danger of drowning. John tried to pull him out but cannot manage it. He remembers his father’s instructions and lets his baby brother get carried into an eddy, and then manages to pull the child to safety.

HW’s account would seem to have been slightly exaggerated for dramatic effect. John’s printed account here would suggest that young Robert merely stepped off the bank into the water (Richard thinks onto weed thinking it would hold him) and couldn’t get back up again.

In the book the fact that ‘Father’ wasn’t told of this (supposed) ‘near-disaster’ was held as a black mark against the other adult: but if he had been told, then one can only too well imagine the resulting to-do! (I am being a little careful with my explanation here – the reason will be revealed further on.)

|

| Margy and John on the plank bridge |

Chapter 21: Companionship (1959 edition, Chapter 11, ‘Threshing’)

We learn that a pair of boxing gloves had been received as a Christmas present, and Windles has become quite proficient.

|

| Windles boxing with brother Robert |

Father takes the older boys for a walk. Margie declines (she wants to see the Hunt) and comforts left-behind Robbie. The ‘men’ go up through Brembridge Wood (again see Salar end-paper map). They see a mole and a worm, and after a bit of fooling and moralising, decide to leave both alone. They watch threshing with a steam engine on a farm and discuss the mechanics of running a farm. HW’s thought here is an important illustration of his reasoning:

I thought of other places, other cornfields, always in blue and gold weather. The wheat was orient and immortal corn . . . until the sudden severance of August 1914, the corrosion of hope, which is illusion, to the bitter dark of death. And after those four years, the bitter dark of men’s minds, the same system of struggle for markets in Europe, the same war arising inevitably if the system were not entirely altered: Windles and John going forth to defend England’s “honour” . . . which meant the satanic international system of usury.

We know HW was re-writing this book in the spring of 1939. We know also that he was writing articles for the Evening Standard at this time (see background notes at the beginning). In an article entitled ‘Immortal Corn’ printed on 26 April 1939, HW quotes those same words. The article is reprinted in Heart of England, ed. John Gregory (HWS 2003; e-book 2013). John gives an explanatory footnote explaining the source of that quotation, which is actually: The corn was orient and immortal wheat . . . (the full quotation is given) from Centuries of Meditations by Thomas Traherne (1637–74, religious mystic and poet – akin to Gerard Manley Hopkins) – written in the 17th century, but not printed until 1908. (Those articles need to be read for a full understanding of HW’s thought and reasoning at that crucial time.)

That mood is broken with description of hunting the rats escaping from the threshing and also a mouse-hunt. Windles stands up for a tormented mouse and is rewarded with a chance to board the steam traction engine and stop it. (Possibly that is all meant to be allegorical?)

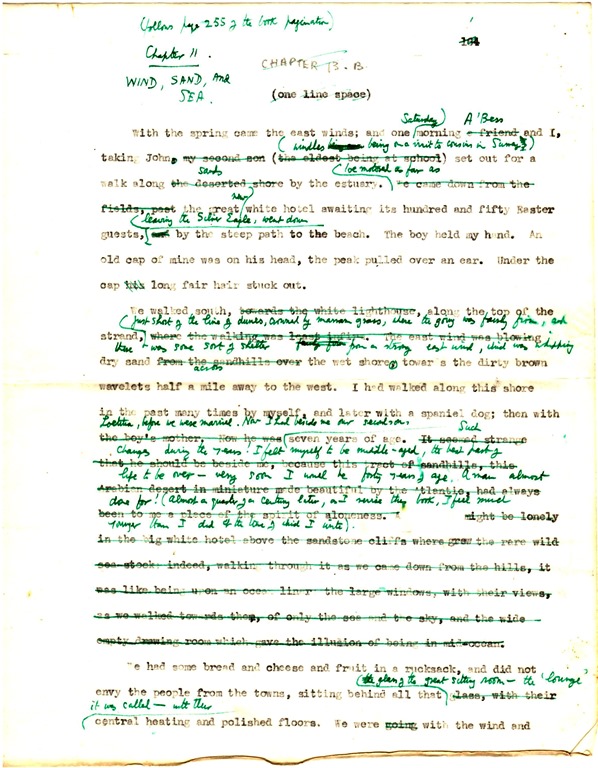

(1959 edition: at this point HW inserted new material for Chapter 12: ‘Wind, Sand, and Sea’ – an extract from Goodbye West Country):

Chapter 22: Innocent Water Buttercup (1959 edition: first part not used, HW note states ‘Used in A Clear Water Stream 1957’; 2nd part is Chapter 13, ‘Life Catches Up’)

HW relates that he had once stopped ‘beside a stream in Wiltshire’ and admiring the water-crowsfoot growing there, and its use as a habitat for various water flies (food for salmon and trout), he bought and filled a bucket with the weed and transplanted it in the River Bray. We learn how it spread successfully and how he devised means to help it further.

|

| Water-crowsfoot in the River Bray |

He only realised, when it had become overwhelmingly prolific, that in acid Devon rivers it could not support the flies of chalk streams and he feared that it would choke the water and kill off the Taw salmon industry. So he set to work equally industriously to remove it, a Herculean task.

From this we learn that he no longer has the desire to fish or even stay in the West Country: he couldn’t successfully uproot the water-crowsfoot so he must uproot himself. Then he discovers Windles, aged 11, is working for a scholarship, and realises that he has four boys to educate: ‘Four young men to be settled in life.’ (Ignoring the young lady!)

He ruminates over his own life and how it affects his family. He takes Windles up on to Exmoor and in discussing and solving the problem they decide to take on a farm. But this is now 1937: in the real world HW had actually decided to take on a farm – the Norfolk Farm – two years before this fictional scene. It is a clever way to introduce the subject of the forthcoming move. He quotes Hodge and His Masters: in 1937 HW was working on the revisions for his new edition of this book by Richard Jefferies.

It is evident that he can see war looming and that to farm is his solution to that problem, with the farm providing a haven for his family.

He also discovers that the water-crowsfoot dies off of its own accord in the drought of a hot summer. All his problems are solved, as he states, by the logic of opposites. (A hint at the philosophy of Plato, which he must have learned about at school: that to know something one must know its opposite – ergo to know good one must also know evil. This is a dichotomy which is entwined into much of HW’s Chronicle writing – the Lucifer aspect which becomes increasingly to the fore with the Second World War.)

HW’s MS note at the end of this chapter reads:

(1959 edition, Chapter 14: ‘Seven Year Cycle’ is also a passage taken from Goodbye West Country.)

Chapter 23: Ancient Sunlight (1959 edition, becomes the first part of Chapter 15: ‘St. Martin’s Little Summer’, but has an added opening passage. This opens ‘April the first’ making the chapter title rather a horrendous error, for ‘St. Martin’s Little Summer’ refers to days occurring around St Martin’s Day on 11 November.)

HW ruminates on time passing, of the human instinct (and his in particular) to seek that lost past (‘à la recherche du temps perdu’). HW states that it’s:

how we depart, and what we leave behind for those who follow on, that seems to me to be the heart of the matter called life. . . .

Only in the past has my being a sense of form. I dream backwards into time. . . .

But the next day he is: ‘going across England to see a farm in a near-derelict district of East Anglia’. (i.e. that is in the future – an interesting philosophical concept in itself here!)

First he stays up to read John’s book.

Chapter 24: John’s Book (1959 edition, becomes the second part of Chapter 15: ‘St. Martin’s Little Summer’)

We have been told in an earlier chapter that when aged 6½ John had had to have a period away from school in order to recover from a ‘debilitating illness’. This was the period following his pneumonia and burst eardrum (which left him partially and increasingly deaf). During that time, as an occupation to keep him from being bored, it had been suggested that he should write a book – like his father. Here we have the result. It is a charming example of childish story telling. However – it is even more charming in his original handwriting, and so that is appended here on its own separate page.

You will note however, that in the handwritten version there is no ‘Chapter 25’ recording how he saved his brother Robert from drowning. No wonder that ‘Father’ was never told about it! One has to presume (sad though it may be!) that this chapter was added later by said Father to add some drama into the tale.

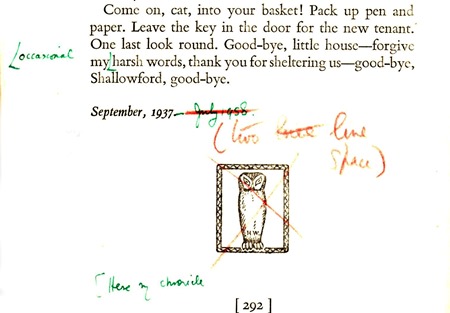

Last chapter: And so Good-bye (1959 edition, Chapter 16: ‘Soliloquy on a Tea-Chest’)

The house is nearly empty. Tomorrow I am leaving Devon and all it has meant to me during the past twenty-three years.

Note HW has taken this ‘Devon’ period back to 1914 – to the time he felt his spirit began to live in Devon.

HW is here relating a visit he actually made back to Shallowford from Norfolk, where he was already installed (while the family had already gone to live with Annie Rawle nearby to Shallowford), travelling down on Sunday, 27 September 1937, and recording in his diary the following day:

Packed things & idled, feeling incoherent. Wrote an article in morning for Daily Express, Goodbye West country.

That article, printed in the Daily Express on 9 October 1937 (reprinted in Chronicles of a Norfolk Farmer, ed. John Gregory, HWS, 2004; e-book 2013), is word for word exactly the same as this last chapter here, except for a few extra words here at the end (the extra words here are underlined – the article merely has ‘Good-bye, West Country!’):

For more than a year I’ve been looking forward to this moment – going far away to a new life, a natural life, of easy body-working; after the strains of too intensive imaginative creation.

Now the moment has come; and ghosts are crying all around me – the ghosts that live and die with a man’s memory.

Come on, cat, into your basket! Pack up pen and paper. Leave the key in the door for the new tenant. One last look round. Good-bye little house – forgive my harsh words, thank you for sheltering us – good-bye, Shallowford, good-bye.

The last chapter in the 1959 edition is more substantial, and even brings in T. E. Lawrence, and his friend John Heygate (who did get to travel on the footplate of such a train – but not specifically to visit HW!)

It includes this rather poignant paragraph:

But it still ends with the same paragraph as the first edition – with the added word ‘occasional’ (harsh words).

*************************

Go to Critical reception

Some family photographs from the Shallowford era

Henry Williamson and Reginald Pound