THE SUN IN THE SANDS

And Life is Colour and Warmth and Light,

And a striving evermore for these.

julian grenfell, from Into Battle.

|

|

|

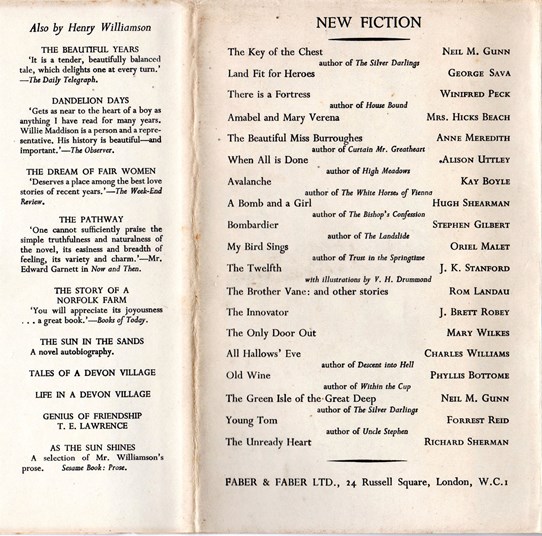

First edition, Faber & Faber, 1945 |

|

First published Faber & Faber, March 1945, 8s 6d

Publisher’s note: ‘This book is produced in complete conformity with the authorized economy standards’

(The published book is 240 printed pages of thin, poor quality paper reflecting wartime restrictions. The text is closely typed, about 500 words to the page – equalling roughly 120,000 words in total.)

Reprinted, December 1945, 8s 6d

The Right Book Club, 1946 (Members: 2s 6d)

Faber (reprint, with slight revisions) May 1948, 8s 6d

Note: The plot found in this book, but extensively reworked and with the ending changed, was incorporated into The Innocent Moon (Vol. 9 of A Chronicle of Ancient Sunlight, 1961). HW’s diary note for 19 June 1960 (when writing The Innocent Moon) states:

Have been working steadily on no. 9 & shall soon finish it. I am breaking down the Sun in Sands for it, & finding that book pretty awful. The rewriting of 1943 ruined the original truthful and simple & un-egotistic Mss I wrote in Augusta [Georgia, USA] in 1934.

Of course, HW’s ideas for the new 1961 work were very different to those that he had for the 1934 volume, inevitably warping his 1961 view of the latter.

*************************

In his ‘Foreword’ to The Sun in the Sands HW states that this book is about the post-war years of the First World War (actually 1921-24) and was written in the USA in 1934, but turned down by the publisher he showed it to as dated and too English. He offers it now in 1945 in the thought and hope that his story of a young man from the First World War aspiring to a vision of a new world and seeking clarity beyond the confusion of human emotions, may be timely: that is, now another World War has occurred. It was perhaps providential that the book was turned down in 1934, for in 1945 its import had far greater significance. From our perspective today those ten-year hops seem to take on an odd significance of their own. Apart from anything else, HW is discarding here all the intervening (highly successful) writing years. His readers are used to this success: Tarka the Otter, The Village Books, The Pathway, The Patriot’s Progress, Salar the Salmon, The Story of a Norfolk Farm. They are now given an intimate view of the struggle of the early years.

This statement of intent does not reveal the whole story by any means, as will be seen. The Sun in the Sands probably has the most complicated genesis of any book that HW wrote. For a start, HW had actually written a great deal of this book well before he went to the USA in the spring of 1934. The manuscript held by Exeter University Special Collections Department consists of pages 1-253, marked by HW as:

end of Part II. 1.30 a.m. 19 Feb. 1934.

Fire out, sneezing, icy-feet.

HW

HW’s diary reveals that he was at his Writing Hut in the Field at Ox’s Cross, Georgeham. He had had lunch and tea with his friends the Lamplughs in the village: ‘and they came up in the evening to Hut & we drank ½ bottle White Horse [whisky] in ½ hour. Or it may have been 1½ hours.’ (And no doubt HW read the new book to them!)

Further, HW’s statement that he wrote this book in Florida is not quite the truth. On arrival in New York he recorded writing most days. And although while he was staying with Mrs Reese in Georgia he did indeed visit Florida on a fishing trip with a new writer friend Edison Marshall, there was little time there for writing. Apart from the major part written while still in England, the rest was written while he was in Georgia, where he recorded writing regularly most days – with a last three thousand or so words when back in New York, waiting to return home.

A small file of manuscript pages still in his personal archive are marked:

End of Phase Two.

Ended at midnight

2 April 1934, Eastern Standard Time,

in Augusta, Georgia, USA:

5 am in England 4000 miles eastwards:

To the dance music of Paul Whiteman

on the radio from the Hotel Biltmore,

New York City.

His diary entry for 2 April, written in Georgia, states:

Played baseball with children [he met in the park nearby], & sunbathed.

TOO HOT, the sun stands up in the sky like the whiskered spirit of a burning tiger.

[Note the association here to William Blake’s ‘Tyger, tyger, burning bright’.]

The published book was advertised as a ‘novel-autobiography’. Although the early phases of the book can be related quite readily to real-life autobiographical facts, the story is increasingly enhanced by a large thread of fiction which eventually turns to fantasy, which totally overrides any factual story-line.

It covers a time-span from March 1921 (when HW went down to live in Georgeham, North Devon) to 1924 (so to the time when he met his first wife – or began to write Tarka the Otter, whichever factor you prefer to use as a yardstick); BUT, by that apparent date, time has melted and merged into a surreal fantasy land.

The book can be seen, with the knowledge of hindsight, as a forerunner of the eventual ‘novel-biography’: the series of fifteen novels that constitute A Chronicle of Ancient Sunlight. Indeed, as stated, The Sun in the Sands is literally incorporated into volume 9 of the series (The Innocent Moon) although HW changed the dramatic ending to fit his later plot-line (this caused confusion in some critics, including a particularly obtuse Colin Wilson – see the entry for The Innocent Moon).

That HW related the circumstances of the Second World War to those of the First is of the greatest importance in our understanding of his psyche – as a man and as a writer. Although this 1934 book was not (and could not have been) written with that particular purpose in mind, it stems from the continuous traumatic state of mind of its author.

HW’s use of quotation from The Hon. Julian Grenfell’s powerful poem Into Battle on the title page emphasises this inter-connection of the two wars. Grenfell (the eldest son of Lord Desborough) wrote the poem just before he was killed in action, and it was published in The Times on the day his death was announced on 26 May 1915. (His younger brother Billy was also killed, at Hooge, two months later in July 1915). Julian Grenfell had been part of the ‘brilliant set’ of young men who had been up at Oxford just before the First World War broke out, who included John Manners, Patrick Shaw-Stewart, Charles Lister, Ego Elcho, Arthur Asquith, Aubrey Herbert, and Bernard Freyburg: most were sons of titled families and most were to die in battle.

HW felt a particular empathy for Grenfell, and he is part of the make-up of the powerful character ‘Spectre West’ in the Chronicle. (See AW, ‘Some Thoughts on Spectre West’, HWSJ 34, September 1998, pp.86-94, particularly p. 91.) HW became a personal friend of Julian’s sister, Monica Salmond (Lady Monica Grenfell), and there is considerable correspondence between them. The lines quoted here:

And Life is Colour and Warmth and Light,

And a striving evermore for these

echo HW’s statement in his Foreword, repeated on the cover flap, that this book is about a young man ‘aspiring to the vision of a new world and seeking clarity beyond the confusion of human emotions’. (The whole of Into Battle is printed in The Golden Virgin (vol. 6, A Chronicle of Ancient Sunlight), p. 72.)

At the end of 1944, the point at which HW wrote his Foreword, the outcome of the Second World War was still very uncertain. Despite the Normandy landings in June, by September the Germans had rallied and the situation was critical. Apart from the crisis within the nation, HW was also in the midst, once again, of a crisis in his personal life – indeed the most drastic crisis of his entire life. Totally overworked with the worries of the Norfolk Farm combined with the need to write to earn money to keep things afloat financially, his marriage was in crisis (and was to end soon after), and all this was exacerbated by the situation with Hitler and the war: Lucifer, the bright star (as HW had once thought him) had fallen to become the Prince of Darkness. The psychological blow must have been immense.

It is increasingly clear that the state of breakdown – or post-war trauma – that HW endured due to his experiences in the First World War continued (although unrecognised or suppressed) throughout his life. It is equally clear that this became increasingly dominant again during the years of the Second World War. That it had flared up during the writing (indeed was the cause of the writing) of The Sun in the Sands will become clear in this exposition.

Having, with peculiar idiosyncrasy (the tautology is deliberate!), suppressed the book after its American rejection, HW now, over ten years later, felt it would carry a meaning to a new generation equally confused by war:

the sky is blue glass glittering with flaws [savour that superb metaphor – the flaws being the hundreds of American bombers flying east, high over the farm.]

He feels – hopes – that the message ‘of a young man aspiring to a vision of a new world and seeking clarity beyond the confusions of human emotion may be timely.’ (My emphases.)

*************************

One would normally begin at the beginning. But in this case it is not totally clear where the beginning actually was. Rather – let us say that there were two beginnings. The first stems from the dates contained within the book itself: the second is the point at which he began actually to write the book. And of course there was a third, when he decided to finally publish it (or was that an ending? ‘In my end is my beginning’ – a concept that becomes of vital import within the Chronicle series in due course).

The second date is very definite. HW’s diary entry for 26 November 1933 states: ‘Began autobiography’. No reason is given for this momentous decision. But several preceding pages have (most unusually) been cut out of the diary here, and no doubt they would have held a clue. However, an examination of all the facts surrounding this event does help to resolve the answer.

Mainly, it was at this point in time that HW realised that his coup de foudre love for the 16-year-old Ann Edmonds was a mirage, despite all appearances, or rather despite all his self-will, to the contrary; an unsubstantial phantasm, although he clung to his illusion until well into 1934.

|

| The young Ann Edmonds |

HW was therefore in a highly charged emotional state of despair; and at such times he nearly always threatened to commit suicide. (This may account for the cut-out pages.) But it seems to me that in this case he actually decided to revert to the advice given to him when he was convalescent at Trefusis House in 1917: write as therapy. (Actually, we have to recognise that all HW’s writing was possibly, although no doubt unconsciously, in fact therapy for him: but here I think it was a conscious rendition.) He had decided to get his autobiography on to record before committing any such catastrophic action.

Pages for 27-8 November have also been removed: the entry for 29 November states: ‘Another chapter to Ann.’ (Ann Thomas, HW’s secretary and mistress, who had just born his child, was living currently at Tenterden in Kent, and typing to earn her living.) The original manuscript at Exeter University has a note on page 22 (the end of chapter 1):

Written 27 Nov. 1933 & last 3000 in Mrs. Shaplands waiting room & later in some Barum pub. ending 7.15 pm. [I have not established whom Mrs Shapland was – but as there are various references to obvious appointments with her I am presuming she was his dentist! After a note to Ann Thomas about typing he continues:] I hope to write it right off. God knows how it will turn out. I’ve gone much deeper than I expected already.

On the MS, page 34 – the end of chapter 2 – he wrote: ‘This chapter written in Lady Renshaw’s house, Instow, between 5-6.30 pm, 29 Nov. 1933.’

And on p. 41: ‘I am so tired, tired, tired, tired, tired, very very tired, tired, tired, so tired. O so tired, so tired, so tired.’

The iris has become transparent

Sense has outlasted sense

There is nought left, save

Logic, safe in the arms of reason

For I am tired, so tired, so very tired.

A little histrionic but it fully illustrates his state of mind.

On 1 December (his 38th birthday) HW left for Bickley in south-east London to see ‘A.C.E.’, which quickly changes to the more intimate ‘Bb’. (Ann Edmonds’ initials spelt out ACE, so redolent of her ambition to fly and later successes in that field, and HW’s pet name for her was ‘Barleybright’, hence ‘Bb’.) The visit followed a pattern of high and low moods. Ann seemed to lead him on but also keeps her distance. He returned to Shallowford on 6 December. The following day, meeting Lord Fortescue (his landlord) and others, who were out on a shoot in the Park, he noted their friendliness:

because, with the theme of Sun in Sands in my mind, & the ultimate farewell, such acts seem to me so generous in a (to me) dimming world.

This statement supports the idea that he was indeed planning to commit suicide.

8 December: Wrote a little more of Sun in Sands. Poor stuff, padding. My article on ‘animal loving’ in D. Mail yesterday.

(This article is not recorded in Matthews, Henry Williamson: A Bibliography; neither do I recollect seeing it in HW’s archive – but presumably it was on the theme of natural love, HW feeling that human constraints made love unnatural, as per his own situation!)

A few days later he noted that he realised Bb will never love him (this is a continual see-saw):

Once again, learn thou fool, that thou wilt find the love thou seekest in posterity only [i.e. after death].

On 15 December he recorded: ‘Daily Mail (Reggie Pound) asked for article on ‘Real old-fashioned Christmas’, which he wrote the next day. (This was printed 23 December 1933, entitled ‘I mean to have an old-time Christmas’.)

At this point he wrote a long letter to T. E. Lawrence with copious details about his love for Ann Edmonds. TEL did not answer; HW realised that he had made a mistake in confiding such intimate details and wrote again: ‘Please wait until you read THE SUN IN THE SANDS.’

On 19 December he drove back to Bickley, also visiting Ann Thomas and seeing her baby (and his!). On the 22nd he drove the Edmonds family down to Shallowford for Christmas, where his great friend John Heygate also a guest. HW did not actually enjoy this, as his emotions were far too raw (and Ann obviously flirted with Heygate, which upset HW!). On 30 December he drove the Edmonds family down to Torcross, where the Edmonds had a holiday cottage – and where he had first met Ann in May 1933. He returned to Shallowford the next day. His diary entry for 1 January 1934 states that Ann Edmonds had indicated that she intended to pursue her ambition to fly, and later would consider HW:

Went on painfully, with chapter 6 of the Sun in the Sands.

And so he continued, all amid his anguish over Ann.

2 January: Wrote steadily

4 January: Wrote about 6000 words of chapter 7

5 January: 3000 words

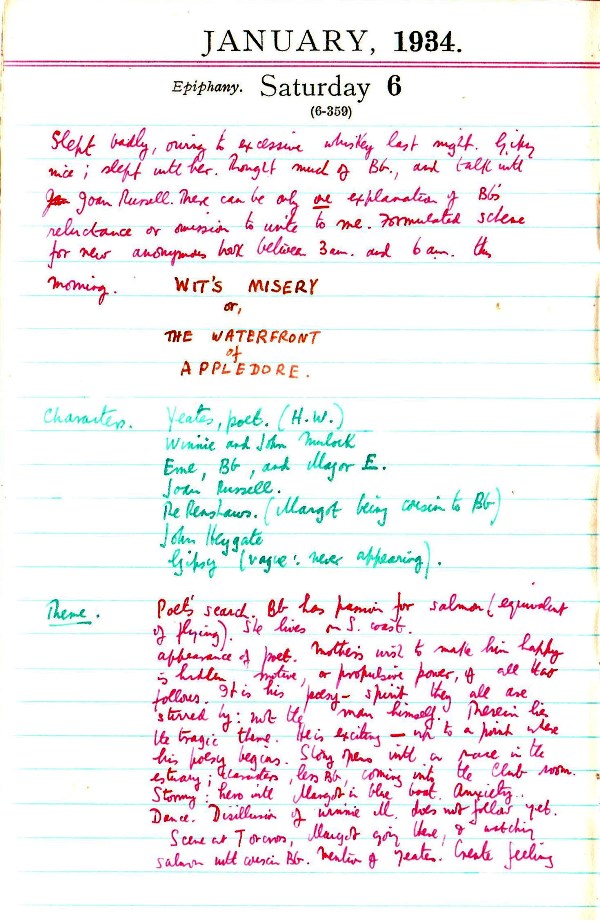

Over the 6th and 7th January is one long entry:

In this very complicated plot outline (which I feel mainly illustrates how disturbed HW was), ‘Yeates, poet’ is not actually his friend Victor Yeates, then currently writing Winged Victory, his novel about his experiences as a pilot in the RFC in the First World War, but rather HW himself. Winnie and John Mulock lived locally (Winnie was another of HW’s conquests at the time – or rather she threw herself at him). Eme, Bb and Major E. are the Edmonds family. Joan Russell was a girl he had met in the pub the previous evening, and liked! The Renshaws had a cottage in nearby Instow, where HW went sailing, and were related to HW’s wife through marriage (Margot Renshaw was one of his most lasting female relationships). (The Edmonds also seem to have been distantly related, as Ann’s middle name was ‘Courtnenay’, which had connection to the Chichester family, with which both the Hibberts and the Renshaws were also connected – all very complicated but it explains HW’s comment.) John Heygate was HW’s great friend, who appears throughout his life and work (as ‘Piers Tofield’ in the Chronicle); Gipsy was his long-suffering wife – ‘vague: never appearing’, rather designating the place she now held in his life.

He continued to write several thousand words each day in early January.

Saturday 6 January: Wrote about 7000-8000 words of SinS today

7 January: Wrote 2000 words, ending chapter 10. Tempted to make Diana into Bb, to reappear at end of book as the sun-maiden. Tired but plenty of energy. This intensive work alleviates the former heavy ache in the breast. [And therefore therapeutic.]

8 January: Anguish over Ann – wrote about 2000 words.

9 January: Wrote about 1500 words . . . Bb is now one of the characters in the SinS. That theme will make the poetic value of the book.

10 January: Wrote about 2500 words of book, completing chapter 12. Feel it is very good indeed; but am doubtful of the ultimate length. About 35,000 – 40,000 words already and still in June 1921! . . . 10pm. Wrote about 800 words of chapter 13, & finished, unexpectedly, Part I. It’s grand!

11 January: Wrote only 1000 words this evening. Chapter I, Part 2.

On 16 January he went back down to Torcross and drove the Edmonds back to Bickley, going on to stay with Dick de la Mare in London, where he also met John Heygate.

On 20 January HW met John Macrae (of Dutton Publishing, USA, who had published all his earlier books up to The Gold Falcon) for breakfast, and promised to send him ‘SinS’. (This was surely unlikely, as HW’s publishers in America were now Harrison Smith & Haas!)

On 21 January he left (from London) for Macclesfield to sit for his portrait by Charles Tunnicliffe, where he arranged for Ann Edmonds to become Tunnicliffe’s pupil. It will be noted how the work for this book is interweaved with the articles he was writing at the time for the Sunday Referee, which became The Linhay on the Downs; thus much of the background covers the same era. It was whilst he was at Macclesfield that he was told by Major ‘Monk’ Edmonds that he must not contact Ann while she was Tunnicliffe’s pupil. He was plunged into the depths of despair and poured his heart out to the Tunnicliffes. It would seem Tunny himself almost certainly just ignored this and got on with his work – but it is evident (from various later ‘outside’ sources) that his wife found it all very distasteful and later held it against him. She probably considered her guest rather boorish.

HW now recorded in his diary an interesting note about this supposed ‘autobiography’.

25 January [in pencil]:

Note for SinS

In first part I search for protection – mother complex – seeing Dream as thing apart. I am so worn. “Mother-maiden”. After marriage, the struggle is undefined by me, between the mother-complex-realization & the sky-maiden. I am healed in part by Loetitia: and absorb that which was missing: and am now ready, in her words, for “my real wife”.

After success or wish-fulfilment I am more vacant than before: the dream is seen as an illusion, & there is no human companionship.

These are the two themes.

Incidents. I see Bb & her mother in London during the writing of Part I of Pathway, before Christmas at Loetitia’s home. Irene speaks of deep breathing: Bb is 9-10 a minute. At length I tell her of my happiness. And the betrothal. I breathe deeply. Why darling, what is the matter, you’re breathing so quickly. I think it’s the air Mummie, I think I’ll go to bed. Goodnight, she said, & was gone. This six months after Pyrenees & the great walk ending in the collapse of the Julia-Joanna Essex [triangle drawn here].

I see Bb again 2 years later, in Pyrenees, January 1927; with her father. I [word difficult to read – possibly ‘resisted’]. “Aeroplanes – not airplanes”. Ski-ing.

Then after Hawthornden, June 1928, I see her photograph parachuting just before sailing for Canada.

She writes in 1932, after G.F. [Gold Falcon]. Then my gradual collapse.

This is all rather obscure but does show the complications of his thought processes. One thing that is obvious is that the person representing Bb is changing here according to the date he is working against, but remains ‘Barleybright’: i.e. Bb is an idealised person throughout made up of bits of all the ‘Barley’ girls he falls in love with. He did not meet ACE (Ann Edmonds) until spring 1933 – which date is after the end of the ‘synopsis’ above. So she cannot be a real part of any earlier ‘Bb’.

(Incidentally, there are several references to ‘deep slow breathing’ throughout this book: this seems to emanate from Barbara Krebs, who stayed with Miss Johnson in Georgeham, with whom HW fell briefly in love.)

The following day he wrote: ‘. . . Managed to write, against the heaviness of death-feeling, about 1000 words of comedy in the SinS. Tunnicliffe portrait of me nearly finished.’

The following day he received the letter from Mrs Sheridan on behalf of Mrs Louise Reese inviting him to stay at her home in Georgia USA (see the entry for The Linhay on the Downs for the full story):

A God-send, a miracle. I shall go and never return. . . .

From Macclesfield HW drove to Bickley (the Edmonds) – then to Ann Thomas at Tenterden – back to Bickley – to Petre Mais at Brighton – back to Tenterden – to Bickley (where he notes Ann said he mustn’t kill himself or she would blame herself for being hard and cruel): a frenetic pace! He saw Mrs Sheridan in London. On 8 February he returned to Shallowford.

10 February: Wrote about 2000 words of SinS.

11 February: Did some more work – about 1500 of SinS

12 February: More of SinS. Mostly from diary.

14 February: Wrote more of book.

15 February: Wrote about 3000 words ending tired, at midnight. The Julia-Joanna-Henry triangle.

Those are the names that appear in the original manuscript now held at Exeter University. They become the ‘Annabelle’ section in the published form.

HW left for America on 28 February 1934. On the train from London down to Southampton to board the boat for USA he wrote the following in his diary:

Coming down from Waterloo to Southampton, tired, thought of end of S in S. John [Heygate] comes up & tells of Bb crash & death; I go to the station & buy all the papers I bought when the B. Years was published; can’t read them; sit on some seat. Then I drive away, & Loetitia says J.H. sit by me (his car) & J.H. says ‘Windles’; & then the end.

?Shall that be dream: & reality be Bb breaking into the dream – the last of the old fearful Maddison?

[It continues with description of TEL & Heygate coming to see him off on the Berengaria.]

Some of this seems rather muddled – perhaps understandably under the circumstances. Note the reference to ‘dream’: which connects to the ‘dream-vision/framed-narrative’ aspect of medieval ‘Romaunce’ writing I have previously discussed (see Anne Williamson, ‘Save his own soul he hath no star’, HWSJ 39, September 2003, pp. 30-60), and which applies to various of HW’s writings.

That note refers to the last section of the book and it is clear that a very large part of the book had already been written by this point.

Arriving in New York on 6 March HW stayed at the Brevoort Hotel. On 10 March, he noted ‘Snowing. Wrote some of SinS, chapter 21.’ It should be noted that the chapter numbers he gives will not (necessarily) equate with the chapters in the printed book – a great deal of revision occurred before actual publication! Comparison of the original manuscript (alternate passages written in brown and green, sometimes red, ink) and the highly annotated typewritten version with all its revision and rewritings is available at Exeter University for the scholar who wishes to study the complete process.

HW took the train down to Augusta in Georgia on 14 March: the next day he wrote about 2000 words in the morning and a further 2000 at night. On 16 March: ‘Sat in the park near the house and wrote some more of SinS, chapter 21.’ 17 March: ‘Beautiful sunny weather continues. . . . I sat in the little park and wrote chapter 22 of SinS.’

On 19 March he received a letter from Tunnicliffe about ACE:

She won’t make good as an artist, being interested exclusively in aeroplanes; & she is incipient “go-getter” & even avaricious, whose ideal is to get money quickly, to have a fast car & to do the things that people with money & sporting tastes do.

He is sending her home on 23 March at the end of her trial month. (Ann did have a certain competence for drawing and painting, especially aeroplanes, and was to illustrate her own work in due course.) Mrs Tunnicliffe also added her own comments on the character of this young girl! They were right in their main assumptions. Ann Welch, as she became, succeeded magnificently as an ATA ferry pilot in the Second World War, and also in the world of gliding and eventually para-gliding. (See HWSJ 46, September 2010, AW, ‘Barleybright . . .’, pp. 56-70.)

At this time HW wrote a long letter to Victor Yeates outlining his ‘novel-biography’ where Part 3 is to be ‘JULIA’, and is to contain Pyrenean adventures where ‘Julia’ crashes to a forlorn foregone conclusion, and Part 4 is ‘ALETHEA’:

who is my sweet but somewhat lost and neglected and sad and really beloved wife but she don’t know it; it is a lovely tribute or will be to her: then the ultimate part 5, BARLEYBRIGHT . . . which will knock you flat with its loveliness and grace and reality . . . and she dies flying to me from the Pyrenees, to my hilltop field . . . crashes in equinoxial gales; and T. E. Lawrence tells me always to write . . . and I leave for the US and the book ends with me poised and an ARTIST . . .

The section titled ‘Alethea’ does not appear in the printed book: instead it is used for ‘Lucy’ (based on HW’s wife, Loetitia Hibbert) in the Chronicle in due course. (The Sun in the Sands was published in early 1945: this would suggest that already, in 1944, when HW revised the 1933 typescript for the book, he had his ideas for the future Chronicle mapped out in his mind to some degree. Indeed other small pieces of evidence support this.)

HW also wrote to T.E. Lawrence on 19 March 1934:

Am writing my autobiography THE SUN IN THE SKY and making a novel of it, with imaginary and true-imaginary characters; the spirit of truth I hope but going anywhere for the [latter or letter]. One of the characters is G.B. Everest . . . [he] is not mysterious; but he is a sort of deus ex azure, at the same time a very human built person; he comes in now and then, a sort of meteor and a presence, very queer, oh it’s a very queer and human and funny and sad and inevitable book, with a walloping crash at the end. I dreamed it, welling-eyed between Brooklands and Southampton that 28 February 1934. It’s true, but imaginary.

(The date is reference to the day HW sailed for America and was seen off on the boat by TEL: HW had taken the train from London down to Southampton passing Brooklands, at that time a famous motor-race track built in a continuous ring with curved banking, making for very exciting racing. See his diary entry for 28 February, quoted above, for this ‘dreamed-up’ end.)

So HW continued with the writing of the book, while enjoying all the interesting events of this amazing period in his life. (For the full background see the entry for The Linhay on the Downs; Anne Williamson’s biography Henry Williamson: Tarka and the Last Romantic; and HWSJ 45, September 2009, Tony Jowett, ‘Williamson in the Deep South’.) For instance, on 28 March he noted that he wrote the ‘chapter of Pyrenees, with JBM & DBWL’. The material for this relates back to a walking tour he took in the Pyrenees in May 1924 with Johnny Morton and D. B. Wyndham Lewis, journalists whom he knew in Fleet Street (both these men wrote as ‘Beachcomber’ for the Daily Express). All his description of the Pyrenees adventure in this book comes from that early walking tour, and also a skiing trip he had there in January 1929 with another friend, Christopher (Kit) à Becket Williams, composer and himself a writer on the Pyrenees.

On 21 April he noted that he wrote some of chapter 28 of ‘To Be an Artist’ – so a temporary change of title here! He was still writing (‘1000 words’) on 25 April on the train, when he travelled back up to New York preparatory to his voyage back to England.

On arrival back in New York, on 26 April, he was again met by his publisher Harrison Smith and a crisis of a different sort. Ann Thomas was supposed to have typed up the first part of the book that had been written before he left England two months previously, and to have sent this to Harrison Smith for his perusal prior to a contract for publication. HW was expecting joyous acceptance of this work. The typescript had not yet arrived, creating a crisis of spirit in HW and a cursing of AT for inefficiency, for he was in total panic that he would have to leave for England without the new contract.

HW was again staying at the Brevoort Hotel, and notes that the following morning he ‘Wrote book while still in bed.’ (This is of importance concerning the ending of the book, as will be seen in due course.)

While waiting, he met with Farrar & Rinehart Publishers (an arrangement made when he first arrived) to see if their terms would be better than those offered by Harrison Smith & Haas: but considered their terms very poor: his next three books for a total of $2000 – $500 on signing contract and $500 for each typescript – BUT only if first book made $1000.

Harrison Smith drove him 120 miles out to his house at Farmington, Connecticut, for the weekend. While there HW notes that [Teddy] Roosevelt’s nephew and wife [Mr and Mrs Cowles] came to dinner:

She [the wife] spoke rather knowingly about T. E. Lawrence etc & also deprecatingly of Michael Arlen who stayed here for his play-collaboration with Winchell Smith who wrote ‘Brewster’s Millions’. [Winchell Smith was the uncle of Harrison, and a rich playwright, who had just died, leaving the house they were staying in to Harrison.]

That comment about TEL becomes significant at the end of The Sun in the Sands as will be seen. HW was an admirer of Michael Arlen, who is also mentioned in Devon Holiday (1935).

On their return to New York HW learns that the missing typescript had arrived.

On 3 May Harrison Smith drove him 25 miles out to the home of his publishing partner Haas. HW did not take to Haas and felt no rapport emanating from the man. It was all a little awkward. They refused to discuss the book until they were back in the office – when HW would be leaving for England immediately afterwards. (This was surely ominous: a positive answer would have given rise to an immediate celebration.) HW records here that these two men pointed out to him that ACE and her parents were obviously merely making use of him. He also noted here what terms he will ask: $1000 down & $500 each for three books.

On return to New York the next day (with HW in a panic over packing!), at lunch with Harrison Smith, he is told that they ‘could not pay an advance as the book would not sell nor print it but would get “sheets” from Cape!’. (HW’s exclamation mark here is probably meant to be ironic: due to the fact that Ann Thomas had actually sent the typescript to Cape first (deduced from a chance remark in the diary) – which was the reason for its delay getting to the US – Cape had kept it for ages; it has to be presumed that he had already turned it down. None of this, though, is ever mentioned outright.) HW made an immediate excuse that he needed to get to the bank before it closed and rushed off. A later diary entry shows that Harrison Smith must have said that he had lost 4200 dollars on the previous book – The Gold Falcon. (This does not seem possible: The Gold Falcon had sold extremely well in the US. HW had recorded in his diary for 8 March 1933 that ‘Dick [de la Mare] says Haas has paid 1500$ but he’s holding cheque owing to USA financial crisis.’ So any loss can hardly be put down to poor sales.)

HW therefore left New York on a low note: John Macrae (his former publisher) drove him to the subway train en route for Montreal, as HW had arranged to take the boat from there, thinking that two days on the St Lawrence River would accustom him to the movement of the ship before crossing the ocean. Unfortunately this did not have the desired effect!

On 11 May, while crossing the Atlantic, and after recovering from seasickness with accompanying four or five days of mental bilge in his diary, although he was reading Hemingway’s The Sun also Rises and enjoying it, he noted:

Yesterday I wrote notes for short stories & children’s book, Tales Told by my Children, or Stories for my Children. [The first mention of this forthcoming book!] Am glad the autob. is scrapped: it was getting unwieldy.

He arrived back on 14 May and took the train to London where he was met, not by Ann Thomas as he was expecting, but John Heygate, who took him drinking which he did not enjoy. The following day he went off to see Ann Thomas at Tenterden, and on the 19 May on to Bickley and ACE. His diary records that he now realised: ‘all arose out of my own feelings . . .’ (and admits in effect that Ann Edmonds is indeed something of an avaricious go-getter, as Tunnicliffe had stated – it was her birthday and she suggested she wanted an MG Midget as a present!): ‘My Barleybright is one thing: and Ann Edmonds another.’ (My emphasis.)

That September HW made quite an extraordinary gesture. He handed over the manuscript (actually the typescript) of the ‘novel-biography’ The Sun in the Sands to Dick de la Mare (of Faber & Faber) as surety against loss over his next book (which was to be Salar the Salmon, contracted to Faber). Ann Thomas took the signed contract for the salmon book and the typescript of The Sun in the Sands to Faber on 1 October 1934, and personally handed it over (as she travelled back to Tenterden). De la Mare wrote that same day stating: ‘The manuscript shall be put into our vaults at once, and it won’t be disturbed until you give the word.’

On that day HW noted that (instead of getting on with the salmon book as one would expect) he began Devon Holiday.

And there it stayed for another ten years, until the book was finally published (after further considerable revision) in March 1945. There is no background information to explain how the decision to publish at that time was arrived at: HW’s main diaries for 1944 and 1945 are missing, as they were taken by Gipsy’s brother Bin (Robert Hibbert) to use in evidence over her divorce from HW (although never used they were not returned).

HW was once again in a state of deep emotional turmoil over his personal life and the war, in addition to his despair at the fall of Hitler into ‘Lucifer’ – the powerful (but often ignored) metaphor he always used. He no doubt really thought that this book would hold a message for those also troubled about the effects of the outcome of this second catastrophic war – a war he had so desperately wanted to avoid.

However, it was probably a great mistake to call the book ‘a novel-autobiography’. That is rather meaningless and was bound to cause confusion. The book contains a story which has the merit of a masterpiece in its own right. While it can – should – be enjoyed and read as a novel, it is also one which reveals many facts and, more importantly, thoughts and ideals of the author’s early writing life. The various notes and points of cross-reference in the following synopsis will show how complex the plot of this book actually is with its intermixing of reality and fantasy, and, above all, will give a glimpse of the processes of the creative mind of its author.

Is it also possible that the death of Barley – HW’s ideal partner who never actually existed – is an allegory for the death of other ideals? Ideals that were perhaps always a mirage? (The significance of the use of the word ‘mirage’ will become apparent in Part III of the book.)

*************************

First edition, Faber & Faber, 1945:

Right Book Club edition, 1946:

*************************