THE PATHWAY

(Vol. IV of The Flax of Dream)

|

|

|

First edition, Jonathan Cape, 1928 |

First published Jonathan Cape, 1928

Dutton, USA, 1929

Many reprints, some with small revisions, but no major revised text

Currently available from Faber Finds

This is the fourth volume of The Flax of Dream, and represents ‘early manhood’ in HW’s original scheme.

Oh, if only I may be able to write it as I conceive it. How great and noble a book it will be!

I must live to write it, - I must, I must, I MUST.

(Entry from HW’s ‘Richard Jefferies Journal’, March 1921, at the end of a long entry about 'The Bludgeon' (i.e. The Pathway) just before going to live in Devon, and in a great state of nervous tension.)

. . . I stopped a moment to climb the hedge and breathe the shining west wind, and to lose myself in the vast colour and light of the sky. Down there, where water gleamed in the plains behind the sand-hills, lay Wildernesse Manor, scene of my book about an ex-soldier of the Great War, who tried to alter the thought of England. All my hopes were in that book. I hoped it would change the pattern of the European mind.

(Extract from The Children of Shallowford, first edition, Faber, 1939, p. 15.)

*************************

When The Pathway was published in October 1928, four years had passed since the appearance of volume III of the series, The Dream of Fair Women, and much had changed in the interim. While out with the otter hunt in the summer of 1924, HW had met Ida Loetitia Hibbert and they married in May 1925. HW’s main energies were put into the enormous task of preparing and writing Tarka the Otter, but in addition, to earn enough money for his family to live on (a son was born early in 1926), he was writing articles which were sold in Britain and America.

HW was by now an experienced and established writer. This is evident in the quality of the writing in The Pathway (compared with the first versions of the previous three volumes), even though it appears to have been written in fits and starts. This volume was never revised, except for very minor and small corrections and additions, and it was the quality of this volume that made HW realise that the first three needed radical revision to bring them up the same standard.

The business file for 1928 reveals that the background to publication was quite complicated (a recurring problem, often due to HW’s own interference!). Collins had published the first editions of the first three volumes of The Flax of Dream and the two intervening nature volumes. But due to a problem, HW had already broken with them and moved to Putnam (who published Tarka the Otter) and he was technically under contract to them. This was complicated by the fact that HW’s friend (and best man) Richard de la Mare (son of the famous writer) worked for Faber & Gwyer and was hoping to obtain this latest work. Meanwhile HW’s agent, Andrew Dakers, reported that Putnam finally refused to pay the £100 advance for which HW was asking (which seems extraordinary after the success of Tarka), thus releasing HW from contractual obligation to them – but that Jonathan Cape were happy to do so. Thus it was Cape who published The Pathway on 28 October 1928 – the same day that HW’s second son was born.

HW set the Ogilvie family home, Wildernesse, in Braunton Marshes which lie between Braunton Burrows and the sea and the estuary of the Taw and Torridge rivers, with ‘The Great Field’ nearby. That this was one of his most loved areas is obvious in his evocative and superb lyrical descriptions. The heroine here is Mary Ogilvie, now based on his wife, Ida Loetitia: Sufford Chychester is based on her father, Charles (‘Pa’) Hibbert. (The Hibberts were closely related to the famous Devon Chichester family – hence the fictional name.) The parson, Garside, is the Georgeham incumbent at that time and Miss Goff is a well-known local character, Miss Hyde. There are several articles within the HWS Journal which give great detail of the real life characters and places: particularly see Tony Evans’s ‘Light on The Pathway’, HWSJ 33, September 1997, pp. 25-41, scanned here in two parts: Part 1; Part 2.

HW was still in post-war trauma (which never actually left him) and articulates in this volume many of his thoughts about the war and its causes, a factor which many critics picked up on at the time as excellent. He was at this time of far-left political persuasion. His thinking about the causes of war and its aftermath (the hollowness of the phrase ‘a land fit for heroes’ – when in reality ex-soldiers were left jobless and destitute) led him, in common with many ex-soldiers, to follow the beliefs of Lenin. He was originally influenced by Richard Jefferies’ socialist principles (mainly on behalf of agricultural workers), but particularly towards the end of the war by the writings of Henri Barbusse, whose left-wing politics and anti-war book Le Feu greatly influenced him. This thinking is incorporated into Willie Maddison’s philosophy in The Pathway – notably in the discussion between Willie and the Rev. Garside. Interestingly HW wrote to T. E. Lawrence on May Day 1928:

. . . I’m NOT an established writer. I am a thin, hesitant creature on whom sometimes descends a falcon spirit, and sometimes that of a moaning dove. . . .

I’ve tried to put this Hamlet in an art form, in ‘The Pathway’ which I finished last week, thank God. After 7 years. . . . [then a mention of the imminent Hawthornden Award, possibly to be awarded by the P.M. --] I feel rather a sneak, because ‘Pathway’ I suppose is Bolshy to the core. An attempt to reconcile Jesus and Lenin. . . . [note again that reference to Hamlet]

HW was overjoyed in June 1934 to receive a letter from the Poet Laureate, John Masefield, who wrote to say how much he had enjoyed The Pathway, that very few modern stories had such power and that he was thrilled to find himself mentioned and quoted. HW pasted this letter into the front of his own copy of the limited edition of the book, with a second letter received later (neither is dated). The latter states that Masefield had now read the previous volumes of the tetralogy and that the work is an ‘astonishing achievement’, and that although he had read Tarka the Otter and HW’s other books, these novels are on a far greater scale and yet are ‘so delicate’. Masefield wondered if they had possibly passed each other, or even met, in the war, ‘on the line of the Ancre’. There is a third letter in the archive, again undated, in which Masefield urged HW to write some poetry as he felt he had more in him than could be uttered in prose.

*************************

Three and a quarter years have passed since Willie Maddison left Folkestone, and The Pathway opens on a very different scene, with a description of a bitterly cold winter night – a description very reminiscent of ‘the Great Winter’ scene in Tarka the Otter, Henry Williamson’s great masterpiece published in 1927, just immediately prior to writing this book.

We are in ‘Wildernesse’, the family home of Mary Ogilvie, her widowed mother Constance, and sister Jean, and their older relatives, Mr Sufford Chychester and his spinster sister, Miss Edith Chychester. The family is completed by Benjamin, the rather harum-scarum illegitimate offspring of one of Mr Chychester’s three sons, all killed in the first year of the First World War. Constance Ogilvie has two younger children who are mainly away at school. Her beloved oldest son, Michael, was also killed in the war.

Jean returns from a visit to friends across the estuary bursting with the exciting news that on the way back she had met up with a man she recognised as Willie Maddison, and that she has asked him to supper. Willie has returned to live in Devon and has isolated himself in Scur Cottage to write a new version of his book on the redemption of the world, now an allegory entitled The Star-born. Henry Williamson himself went to live in North Devon in 1921, renting a cottage in the village of Georgeham which he named ‘Skirr’.

The reader knows of course that Mary has always been in love with Willie, but she now has a serious admirer, Howard Wychelhalse. Things are complicated by the fact that Jean is secretly in love with Howard, but in her turn is being pursued by the son of a local farmer. Another friend, Diana Shelley, descended from the great poet (Willie’s hero), is also in love with Willie.

The Pathway is divided into four sections representing the seasons, and the story follows the attributes connected with them: Winter, a time of dormancy and unawareness, the freshness and expectancy of Spring, swelling to the warmth and ripeness of Summer, then dropping to the sadness of Autumn.

The human storyline leads us through the intimacies of the life of the countryside of that very beautiful area of North Devon, the estuary of the ‘Two Rivers’ (Taw and Torridge), the inland marshes, and the wild sand-dunes of the Santon Burrows (Braunton Burrows). Here Mary is shown in her true worth, shy in spirit, the stalwart worker for her family and the sensitive lover of the beautiful things of nature, birds, flowers, insects and stars.

Willie is always totally obsessed with his thoughts of the troubled world and the book he is writing, a surreal allegory, peopled on one level by real people of this world and on another by spirits from an unseen world, and where a Christ-figure – the Star-born - comes back to earth but whose ideas are rejected by the world. Willie’s constant articulation of his thoughts make him a difficult person for those about him to be with, and his ultra-sensitive nature means he swings from exaltation to despair, and takes hurt at every remark made by everyone else and is misunderstood nearly every time he speaks himself (exactly expressing HW himself!).

However, in high summer Willie declares his love for Mary and she shyly admits she has loved him from her earliest days. The highlight of the summer is the Otter Hunt Ball, and the family make up a party, including Willie Maddison. The weather is about to break with a storm; Mrs Ogilvie is voicing to herself her deep worries and misgivings about the relationship of her daughter with a man about whom she is beginning to hear disquieting rumours. So ominous rumblings, literally and metaphorically, are in the background. The storm that eventually breaks that night heralds the end of the summer happiness.

After the storm we enter ‘Autumn’, and have a totally different scene and atmosphere. Willie’s tortured spirit is not destined to find an idyllic peace and happiness with Mary. Thwarted by the disapproval of the Chychester family and other local worthies, he decides to leave Devon. His cousin Phillip appears on a walking tour with the flamboyant poet, Julian Warbeck. Overnight, Willie reads to them, and the local parson, Mr Garside, the whole of his now finished manuscript of The Star-born. They are all completely overwhelmed by its beauty and Truth.

Willie packs up and leaves, calling at Wildernesse to say goodbye to Mary, but is not allowed to; and so, leaving a message which Mrs Ogilvie does not deliver, continues down to the estuary where he plans to get a fishing boat to take him across to Appledore. Unknown to him the fishing season ended the previous day: no boats will come. (But Mary knew this, and if his message had been delivered she could have warned him.) As he waits on a tidal island in mid channel, the tide rushes in. To try and attract attention, Willie lights a fire with the only means he has – his manuscript of The Star-born. The following morning Mary walks on the shore and, finding charred pages of his manuscript, realises the inevitable. Willie has been drowned as his hero Shelley had been similarly drowned in Italy many years before. Mary, very dignified in grief, joins with Phillip and Julian on the shore around a huge fire the men have made, as was made for Shelley: and they mourn his death.

*************************

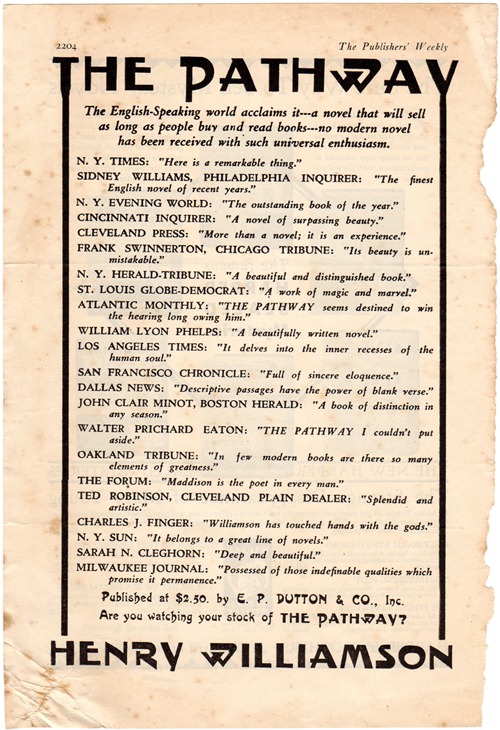

The book was very well received – indeed many followers of HW’s writing today say it is their favourite HW book. But, as always, HW tended to do himself down by saying that the book had not done well. The pile of reviews is enormous and tells a different story: further, suffice it to state that Jonathan Cape reprinted the book four times in the first year, while Dutton in the States reprinted it ten times between February and June. It came, of course, hard on the heels of the award of the Hawthornden Prize for Tarka the Otter in June 1928, and the attendant literary excitement. Even so, the book did seem to puzzle some reviewers. There was a big difference between those who understood and grasped and were sympathetic to its message and those who did not.

It is difficult (impossible!) to encompass here the large number of reviews in HW’s archive, some of them very long. It would almost constitute a book in itself. This can only give a small flavour, but it does enhance our understanding of this very important, and (perhaps today) under-rated and under-estimated book, and of HW himself – for he is indeed Willie Maddison in essence. The detail related in many reviews reveals the impact that this book had on so many established and experienced critics: a factor that may make modern readers open their minds to its message.

(Undated reviews below were certainly written soon after publication. They were possibly cut out by HW himself or sent direct from Dakers – i.e. not from a cutting agency, which always dated cuttings).

J. C. Squire (Sir Jack (John) Squire), a noted critic, who had sponsored HW for the Hawthornden Prize), wrote a long review in The Observer (no date on cutting). He opens with noting the leap in style from ‘the early and callow novels’:

‘The Pathway’ is a very remarkable book, and the man who could write it was born to be a novelist. . . . The book will not appeal to everybody . . . It is about a young man of genius whose war experiences have left him restless, neurotic, visionary, passionately impatient of the cruelty and obtuseness of the world . . . it is about nature and man in North-west Devon. . . . The action is largely psychical; ordinary things . . . are charged with emotion and dramatic suspense. . . .There are, when Maddison harks back, very fine glimpses of the war, particularly one of the Truce of Christmas 1914. There are soaring and blissful passages about nature and fierce outbursts against war. . . . What is not convincing is the climax, which is inadequately precipitated: the ending is a fine tragic ending in its way, but we do not see why it should have come just then.

Arnold Bennett in the Evening Standard and also the Glasgow Evening News (no date), ‘Books and Persons’:

One had anticipated ‘The Pathway’ with unusual interest [due to Tarka] . . . it must be read. But Mr. Williamson has still to learn a few things about the novelist’s supreme job of being continuously interesting. He is a bit too ruthless with the reader. . . .

Mr. Williamson is without doubt a novelist, though perhaps excessively (for an artist) preoccupied with the spiritual consequences of the war. . . . he makes pictures which – I should say – have in their line never been surpassed. The opening scenes . . . are masterly . . . in landscape [he] is a creator of loveliness. But . . . too much of [metaphysical ‘other-world’ insertions] . . . The final tragedy is not made plain. At the crucial point the author has, in my opinion, funked his big scene.

‘The Pathway’ is a novel richly worth quarrelling with. The author’s gifts are authentic and dazzling. He has yet to show himself the master of them.

[On the fly leaf of a file copy of the book, HW, noting that it was queried by J. C. Squire and Arnold Bennett as ‘obscure’, justifies his ending: ‘I claim that the end is not fortuitous: but the cumulative and cumulating episode in a series of ironic and tragic relationships: . . . Actually it is credible, actual, and ironic . . .’ HW goes on to explain his reasoning – that the hero – shown as a bit of a ne’er-do-well – is true to HIS purpose – but self-righteous Mrs Ogilvie does not keep HER promise and thus, by defaulting, causes the death of this ‘unreliable’ visionary. This criticism obviously worried HW. It does seem a strange point to have queried, even as mildly as it was. The end is surely inevitable, given HW’s central thesis.]

Edward Garnett in Now and Then (no date) – succinct and percipient:

[the story is told] against a great background of living nature, of shore and sandhills and marshland, in wind, rain and sun, with the ebb and flow of the estuary tides and of the sea breaking on the river bar. The book’s atmosphere is permeated with these influences, hidden and visible, of nature’s life . . . Mr. Williamson, a follower of Richard Jefferies, is the only living novelist who has created a hero and heroine endowed with this love of wild things and this larger sense of nature’s infinity. Maddison, this ‘queer young man’ . . . his passionate heterodox thoughts and feelings provide the book’s arguments, his strangeness and alienation from his fellows, its tragedy. . . .

Maddison, an ex-officer, has come back from the War and its hellish futilities to find people carrying on the same, unchanged in heart, glorifying the old idols. Maddison stands for the host of men broken and deranged by the War, men without ‘prospects’, who could find and could fit into no place on returning. . . .In Maddison’s pathetic figure, this nature-lover, disciple of Shelley . . . who is slightly touched in the head by man’s inhumanity to man, Mr. Williamson has created a figure of vital interest to all.

One cannot sufficiently praise the simple truthfulness and naturalness of the novel . . . [but] it is too full, too copious in flow, too rich in detail . . . . but for such an original book . . . we must indeed be thankful.

The Times [undated and unsigned]:

A remarkable novel . . . nor is Maddison’s idealism and fierce rebellion against cruelty in any form ever less than interesting. Mr. Williamson appears generally in sympathy with his philosophy – which might be called Christian communism. He will be regarded according to the reader’s temperament [to some a Christ-figure, to others a pathetic being – BUT the author’s] conception is original and he has lived up to its standard in his execution. Think what we will of Maddison, we are not likely to forget him in a hurry.

O. F. Theis in The Illustrated Sporting and Dramatic News (Nov. 24, 1928) in a regular column ‘Men and Events’, a long full-page article titled ‘Nature, Human Nature, and Mr. Williamson’:

‘The Pathway’ . . . a curious book, full of high imagination and also of incredible immaturities. . . . It is particularly in his reflections on the late war that Maddison is most effective. He went through it and it seared his soul. In point of fact, it was the war that gave him his peculiar angle on life. . . . [Article illustrated by a photograph of HW by E.O. Hoppé.]

L. P. Hartley (cutting source not named):

‘The Pathway’ is an extraordinary book. . . . Maddison is the hero of the story, a visionary, an idealist, a poet. His nerves have been ruined in the war, and he is full of bitterness against the condition of things that made the war possible. He is engaged on a prose-work, which apparently advocates some sort of Return to Nature . . . his ideas cease to be convincing directly he formulates them. . . . But as a man, of the stamp of Shelley, or Alyosha¹, fired and consumed by urgent spiritual longings, he is much more convincing: he has the tiresomeness of the fanatic and the impracticability of a saint. He would have been a hopeless husband . . . But it is his presence which gives the book its essentially English and Romantic and Gothic character. ‘The Pathway’ . . . is like a landscape by moonlight, full of mysterious distances and objects of varying visibility. And yet it is not indefinite or woolly. There are half-a dozen characters very sharply drawn, scores of separate scenes that are as individual as a melody. And the emotion and expression of emotion have a flute-like quality (birdlike I will not say) sad and touching and pure. . . . Only in the dénouement does it fail . . . Shelley has already been mentioned too much – and to recite Swinburne in the neighbourhood of the corpse in the highest degree theatrical, a conclusion unworthy of a beautiful, moving, and original book.

[¹ ‘Alyosha’: a reference to Alyosha Karamazov – the youngest brother (and hero) in Dostoievski’s The Brothers Karamazov, a novice in a monastery, sent out into the world to do good. His role in the novel is as ‘messenger’ and he is depicted as kind, loving, sensitive, an almost Jesus-like character. It is thought he is based on Dostoievski’s friend Vladimir Solovyov, the Russian philosopher and poet who is known to have given away his clothes to poor people in the street. L. P. Hartley is paying HW a great compliment by this comparison; he has also exactly pinpointed in his use of these metaphorical examples HW’s purpose.]

J. B. Priestley, ‘A Bookman’s Week’ in the Evening News:

‘The Pathway’ is . . . beautifully written and the whole background of the North Devon coast is wonderfully observed and described. . . . If the whole story were as exquisitely presented as the natural background, Mr. Williamson would have written a masterpiece. . . . the beginning has sheer beauty and the end is quite moving but between the two it sags badly. [Maddison] is half-baked. He has all the trappings of a prophet without a prophecy . . .

There is no evidence that Mr. Williamson is a man of ideas, and he will be well-advised to assume he is not when planning his next novel. I hope he is planning a next novel, because he can write.

Sylvia Lund, in Time and Tide (undated), had a wry slant:

‘The Pathway’ is a grave, beautiful and fascinating book. . . . Its story is simply the progress of a love affair between a man without a penny, who praises Lenin to the vicar and denounces war at an Otter Hunt ball – and Mary Ogilvie with her elder brother a dead soldier and her little brother a cadet at Dartmouth and her mother . . . indomitably convinced of the soundness of her family tradition.

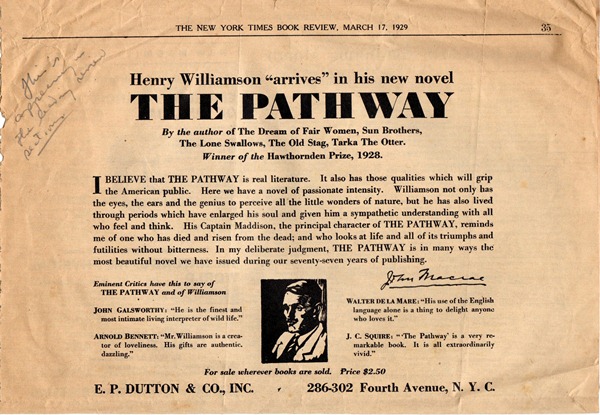

There are many more reviews of the English edition but all are in similar vein. However, it was publication of the American edition by Dutton in February 1929 that gained massive attention. The book was reviewed across the length and breadth of the USA – every publication seems to have taken note of it. This was attended by an amazing literary storm created by the director of E. P. Dutton & Co., John Macrae, who put forward The Pathway as (the only credible) choice for ‘The Book of the Month Club’ committee; but the committee, to Macrae’s total incredulity, rejected it in favour of what he (and many others) considered a hack work. Macrae decried this whole system, exposing it as based on rampant and corrupt monetary gain. (For further details about this affair, see AW, ‘The Amazing Storm that attended “The Pathway” in the USA’, HWSJ 20, September 1989, pp. 34–37. This journal also contains other ‘Flax’ material, including a reproduction of a full page broadsheet of review quotes on The Pathway.) This controversy, combined with Dutton's advertising campaign, made critics and reviewers look at the book closely right across America.

Edward Weeks, in his ‘Bookshelf’ column in Atlantic Monthly (interestingly also reviewing here Memoirs of A Fox-Hunting Man by Siegfried Sassoon), after an introductory paragraph regarding HW’s past literary history and association with the Atlantic Monthly – for the background of this and full articles, see Henry Williamson, Atlantic Tales, HWS, 2007; e-book 2013 – continues:

‘The Pathway’ is set in Devon, the countryside where, since the armistice, Williamson has dwelt in a hermit’s stronghold . . . His knowledge of birds and beasts, of trees and stars and flowers, might have been inherited from W.H. Hudson . . .

The story has to do with a modern Shelley . . . [who] can be suspected of having much in common with the author. The Shelley [Maddison] is ‘a creature of light’, a mystic, erratic and profound in his approach to the business of life. And, like Shelley, his contradictions of the established order brings suffering to himself . . .

Marguerite Kerns, Grand Rapids, Michigan, 10 March 1929:

A Shelley-like idealist, half poet and half saint, is the hero . . ., an exquisite, troubling piece of fiction that takes its charms from Mr. Williamson’s unsurpassed eye for nature and its imperfections from his over-sensitiveness for the sufferings of human nature.

‘The Pathway’ though [set well after the war] is essentially a war book, one of the powerful emotional argument for peace . . . Maddison finds himself odd man in a pastoral little community chiefly because he wants to apply too literally the Christian principle of universal love and brotherhood. . . . he is contentious about nearly all the things that the men and women about him accept as settled conventions.

Aaron Marc Stein, New York Evening Post (no date):

Mr. Williamson is a mystic who does not hesitate to identify himself clearly with the Romantic movement. His novel is an attempt to express in prose the images and ideas which inform the verse of Blake and Shelley. It is an extraordinarily successful attempt, and its success as a novel is directly attributable to the fact that Mr. Williamson is a poet . . . Maddison [has] that innocence of Blake and Shelley which is conscious of itself as a direct intuitive contact with the cosmic reality . . .

Leila E. Bracy in Detroit Free Press (a very long review):

. . . [Maddison] is set apart from all the world and is a sort of modern Shelley. He is impatient and wrathful against wars and the sort of patriotism that plants the seeds of war by glorifying it. He is impatient against Christians . . . who lack charity and mould children in a stern pattern besides refusing to tell the truth about life. . . .

The story of Maddison is in a sense the story of Christ – the story of every reformer who dares to oppose the existing regime.

‘R.B.’ in an unnamed paper:

[For the persevering reader] his reward will be some of the most subtle and musical prose that one is likely to find in contemporary literature. . . . Above all, his sympathy will be stirred by the carefully wrought picture of Maddison, the young poet . . . His mysticism is received as the groping of an immature mind or attributed to shell shock, his vision of the Christos considered an insidious and revolutionary doctrine, opposed to capitalism. He is alone and misunderstood, a tragic and futile figure, tortured by his inability to make others perceive his vision, and doubting often whether his vision is not a chimera . . .

Williamson’s mystic is a miserable and futile figure, but at times ecstatic and sublime. One may not agree with his poetic vision of the world but one can not fail to sympathise with his brave but ineffectual struggle to realise it. . . . [This novel] stands out for its sincere earnestness, for its magical creation of atmosphere, for its beautiful prose.

John Chamberlain, New York Times Book Review, 10 March 1929 (again in a long and detailed review), headed ‘Mr. Williamson’s Portrait of a Mystic’:

Here is a remarkable thing: a novel about a mystic . . . and it is Mr. Williamson’s supreme achievement that he has not made himself ridiculous. . . . For his saintly protagonist, William Maddison, is a creature so sensitive . . . [and] is the sort of person that the world calls insane if he fails . . . and is honoured as a prophet if he succeeds. He is like Shelley, like William Blake, like Spinoza, like Jesus; he believes so intensely in compassion, in the “Light of Khristos”. . . . [But] there is much more than a saintly figure in ‘The Pathway’. The detail is magnificent – opulent – yet restrained by the dictates of an artistic conscience that insists upon line-by-line clarity. . . .

Maddison is an ex-army officer who has seen the corpses rotting in the fields of France. He has fought the war for God and Britain, only to [become totally disillusioned with war and to] realize that the German soldiers opposite him are fighting for God and Germany. . . . he reacts from the war with violence. He takes Shelley seriously; he takes the historic Jesus seriously.

The end is tragedy . . . for Maddison is torn to pieces mentally by the conflict between his vision of what life should be [and what it inevitably is]. At the last he is drowned, as Shelley was drowned. . . .

Herschel Brickel, Weekly Book News (February 1929), on the cutting of which someone from Dutton, possibly John Macrae himself, has written, ‘One of the most important New York Critics’:

‘The Pathway’ is the book of a man who has looked upon the world and found it full of cruelty and beauty. . . .The poet’s [Willie Maddison] god is Shelley, who like him, beat his wings in vain against a world too hard . . . any man [not willing to accept the cruelty of the world] must inevitably come to disaster. The poet . . . thought also of the spirit of Christ . . . [he] had seen from the trenches what the war was like . . . on one occasion seen the British and German soldiers fraternising at Christmas, even exchanging gifts across the barbed wire of No-Man’s Land . . . this expression of brotherly love . . .

‘The Pathway’ – the title itself is to be interpreted symbolically – is a tragic book, as the realisation of the futility of protest against cruelty must always be tragic, but it is by no means lacking in beauty. And no matter how seemingly useless the sacrifice made by Maddison [as has been made by many such before] it is a sacrifice that will go on being made for ever.

Alice Beal Parsons, in New York Herald-Tribune, 3 March 1929:

This is a beautiful and distinguished book. One can disagree with Mr. Williamson on every page, yet go away with a heightened perception of life. . . . It is the part of the poet and mystic to try to pierce the darkness with his own peculiar light. The saint as hero has always aroused intense opposition, whether in real life, like Shelley, or in the pages of a book, like Dostoievsky’s idiot.

Arthur Busch, ‘Page After Page’ Brooklyn Citizen, 10 March 1929; his review is headed ‘Henry Williamson’s “The Pathway”, a Noble Book Which Grasps, and Holds, Elements of Christ, Shelley, Hardy, and the mysticism of Blake’:

Every now and then an authentic cry comes out of the wilderness, a beautiful cry, clear and disturbing, to bid us follow the pathway to truth and beauty and to make us feel ashamed of the mess we’ve made of the world. . . .

In the central figure . . . Mr. Williamson has symbolised the travail and pain of the hopeless idealist who goes through this short span with the cruelties and the hypocrisies of civilisation tearing deep wounds in his soul. He is a Shelley and a Christ . . . Maddison [it would appear] is the author himself; a young man who went through the tempering fire of the World War and was kindled by the mysticism of Jefferies and Blake. . . . It is out of such a state of mind that we get poetry and glimpses of the beauty which lies beyond unseen by our mortal eyes. In the face of realism . . . Williamson may be accused of immaturity; his point of view is often adolescent, often hopelessly idealistic. . . .

. . . the style of Williamson’s writing. The prose wells up often into lyric poetry; in it is the music of Nature, crystal clear and pure. I know of no modern writer whose ear is so amazingly attuned . . . his perception remarkable and his ability to render in prose, positively uncanny.

And so I say that, in spite of its shortcomings, ‘The Pathway’ is a noble book, for in it deep and abiding love sings its song with passionate sincerity. . . . There is in it the spirit of Christ and Shelley and Thomas Hardy and the mysticism of Blake.

Zona Gale, in a long review in The Bookman (New York, September 1929), wrote:

For its four hundred pages The Pathway gives one sensation: that of hands groping against walls, of the actual slow flow of a current towards its cataract; of the malady of isolation; of old hunger for something beyond “the known” . . .

That is but a sample (though a good sample!) of the many cuttings. But there is one more worth noting, found among a selection of short mentions of the 1969 Faber paperback edition of which most English newspapers, although reveiwing it, give no more than cursory attention. It is unsigned, and from the Sunday Statesman, Calcutta, 21 December 1969. It is percipient and interesting in the light of ‘time passed’ (forty years and another World War):

‘The Pathway’ is the fourth novel in Henry Williamson’s study of childhood, youth and early manhood, which together forms ‘The Flax of Dream’. Willie Maddison, now a veteran of the First World War, comes to the windswept Taw estuary in North Devon, in a vain attempt to express in writing the full impact of his years in the trenches and the horror of Verdun and the Somme. The older generation still clings to a Rupert Brooke vision of war, and fully endorses the terms of the Versailles Treaty. Maddison’s ideals have not been dimmed by experience, but rather redirected; yet the generation gap has become insurmountable.

Williamson portrays in Willie Maddison a ‘lost generation’, whose tragedy is much greater than that of Wilfred Owen or Edward Thomas, for they are the generation who survived; only to find that ‘a world fit for heroes’ was a mere illusion. Maddison is at once an individual and a representative, the four novels forming the chronicle of a generation’s dilemma and one man’s tragic response.

*************************

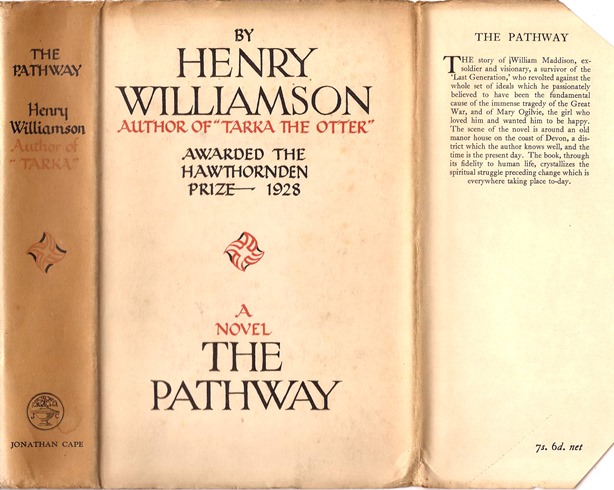

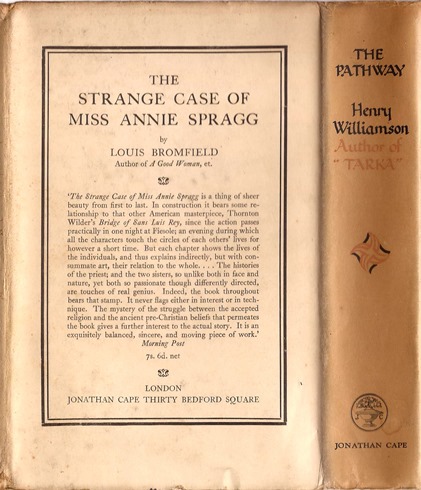

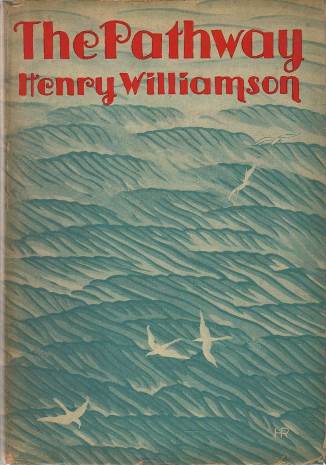

The dust wrapper for the first edition, front and back, a classic Jonathan Cape design:

|

| First US edition, Dutton, 1929 |

Some other covers of different editions of The Pathway are shown at the bottom of The Flax of Dream page.

Back to 'A Life's Work' Back to 'The Dream of Fair Women' Forward to 'The Star-born'