Henry Williamson: Mad about Motors

Anne Williamson

Henry Williamson, mainly known as a nature writer and author of over sixty books, including the famous Tarka the Otter, Salar the Salmon, The Gold Falcon, but also A Chronicle of Ancient Sunlight (a semi-autobiographical novel in 15 volumes where most of the characters are based on real-life people) and indeed many other books, had a possibly little-known aspect to his character: he was mad about motors. His passion is chronicled here in five 'laps'.

LAP 1: On two wheels

LAP 2: Two wheels plus an engine (Nortons)

LAP 3: Four wheels (Peugeot to Alvis Silver Eagle, via Auto Union)

Appendices: The Alvis Silver Eagle (photographs); and Adventures with Alvis Silver Eagle DR6084, by Alex and Elspeth Marsh

LAP 4: Moving up a gear (Aston Martin to MG Magnette)

Appendices: Tale of a Two Litre; and Aston Martin Statement

LAP 5: The car that never was (Bédélia)

On two wheels

It all began with a Starley Rover ‘safety’ bicycle. Henry Williamson’s father, William Leopold Williamson, was a very keen bicyclist. We know he had one of these prestigious machines in the 1890s, because it is detailed in The Dark Lantern, the opening volume of HW’s A Chronicle of Ancient Sunlight, where the main character is Richard Maddison, very closely based on HW’s father. We read in the opening chapter that Richard (still a bachelor at this point) went for rides

on his safety bicycle, which he kept beautifully clean, he never forgot to dust the wheels first before bringing the machine into the house . . .

James Starley (1855–1901), having worked with an uncle on Ariel cycles, started his own business in 1877. His chief concern was to design a bicycle that was safer and easier to ride than the ‘ordinary’ or ‘penny farthing’ bicycle, and in 1885 he produced the revolutionary ‘Starley Rover Safety Bicycle’, with two wheels of the same size, chain driven and with rear wheel drive.

|

| J. K. Starley on the Rover |

In chapter 5 of The Dark Lantern, ‘Surrey Dawn’, Richard sets off for a holiday in the West Country on his

Starley Rover bicycle, cleaned, oiled, and all ready for the adventure . . . mounting his low Starley Rover by the step extending from the back axle, [he] sat on the saddle and pedalled away down the dim road . . .

(Illustration taken from Barry Kitts’ article ‘Wheeling Down to Easterbacon’, HWSJ 42, September 2006, pp. 77–92. The article contains much interesting background into the history of the bicycles that HW writes about.)

As we are told that Richard had Dunlop pneumatic tyres on his trusty steed (‘the pneumatic tyres certainly gave an added speed’) his Starley Rover would have cost £25 – a considerable sum in the 1890s. In the novel Richard’s salary is one hundred and ten pounds a year as a clerk at Doggett's Bank. (Presumably this was the salary of William Leopold as a clerk in the National Bank in the City.) That works out at £2.2s. – two guineas – per week. His board and lodging were 10/- a week (50p in current money – although one cannot make such a direct comparison). So even allowing for other expenses such as travelling to work, being a very thrifty man Richard (and so William Leopold) could certainly have saved up the required sum over the five years he had lodged with his landlady while working at Doggett’s.

We learn that his preferred attire when cycling was knickerbocker trousers coupled with a Norfolk jacket. No doubt he cut quite a dashing figure; but we also read in the novel that his awkward manner and hidebound attitudes earned him the nickname among local ruffians of ‘Jesus Christ on Tin Wheels’.

In about 1904 Richard, now married with a son, Phillip (based on HW himself) and two daughters, progressed to the equally prestigious Sunbeam, as we read in the second volume, Donkey Boy:

[The] new, magnificent, all-black, gold-lined Sunbeam with Little Oil Bath and three-speed Sturmey–Archer gear.

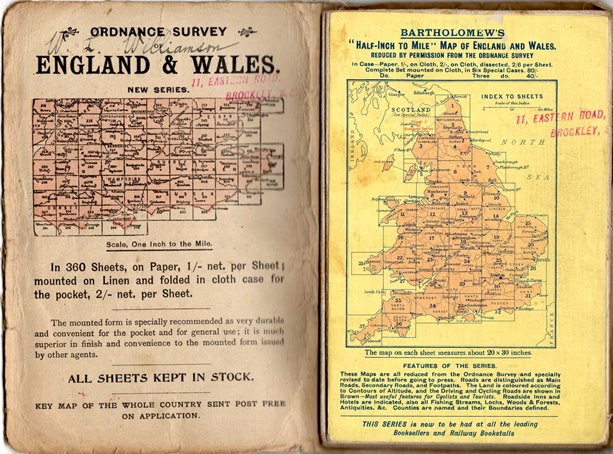

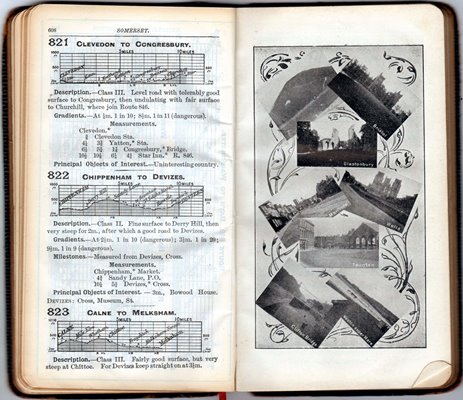

A splendid episode describes how Richard joins the family, who are holidaying on Hayling Island, for two days only, having cycled from their London home in Brockley, en route for his own solo cycling holiday exploring Dartmoor. William Leopold's cycling maps still exist, well used and fragile; some examples are shown below:

|

|

|

| William Leopold's cycling maps for North and South Devon | ||

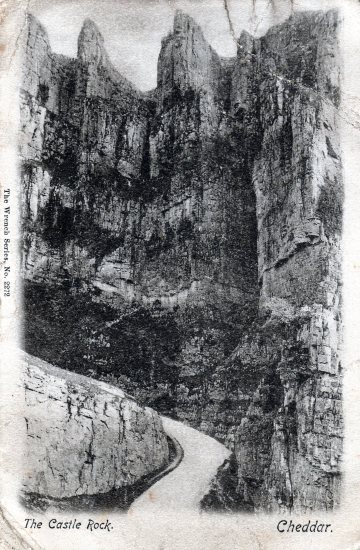

There are also a small number of postcards that he sent back to his wife, one of his daughters (which of the two is not clear), and a work colleague from these annual adventures. Some of the postmarks are indistinct, but the first two appear to have been sent in the early 1900s, while the last looks to be dated 1913.

The impression one gains from various of HW’s writings and personal papers is that William Leopold Williamson used cycling as a means of escape from his family for holidays alone in the West Country.

And it is that concept of ‘escape’, made so obvious by his father’s behaviour, that may have subconsciously impressed itself on HW’s very impressionable young mind. Certainly his own first solo cycling adventures were an escape from the strictures of family life in the south-east area of London into the freedom of the nearby countryside, with its big estates and knowledgeable gamekeepers, where he absorbed much of the country lore that was to dominate his whole life.

Young Harry (as he was known as a boy) started with a second-hand Boy’s Imperial, as related in Young Phillip Maddison, where we read a description of a cycle ride undertaken with his father.

Thereupon Richard put one brown, single-strapped leather cycling shoe on the step projecting from the hub of his rear wheel; grasped the grips of his handle-bars firmly; pushed off with the right foot, and then, rising almost horizontally along the length of his Norfolk jacketed and knickerbockered body, adjusted himself to saddle and rubber pedal: a familiar sight to many who lived in the flats. It was almost a ceremony when Mr. Maddison mounted his all-black Sunbeam with the Little Oil Bath.

Phillip’s bike was a second-hand Murrage’s Boy’s Imperial Model, costing two pounds nineteen shillings and sixpence when new. He had not had it long. Richard had chosen and approved it from a second-hand shop near Wakenham station, priced thirty shillings.

(‘Murrage’s’ is the famous London store Gamages.)

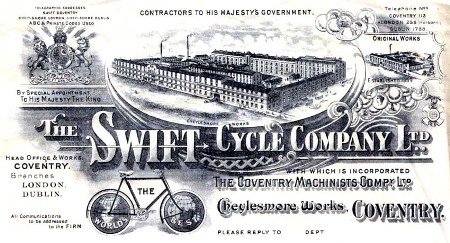

But very soon Phillip has his eye on a 3-speed Swift:

A new 3-speed Swift, like the one in Wetherley’s window, [which] was £4.19.6d.

And indeed, in 1907 aged 11, when he wins a scholarship to the prestigious Colham Grammar School, his dream becomes a reality so he could ride back and forth to school. The novel tells us:

The half-yearly payment of the scholarship grant into his Post Office Savings Account enabled him to buy . . . a new Swift bicycle with 3-speed gear, on easy payments . . . It was black, lined out in gold. He kept it oiled and clean, like the Sunbeam . . .

It does not seem likely that HW’s father actually allowed the young boy free access to his scholarship grant. William Leopold probably bought the Swift for his son when he indeed won the scholarship to the nearby Colfe’s School in Lewisham; but of course the money would almost certainly have come out of his scholarship fund.

His bicycle gave him the opportunity to escape the rather stifling atmosphere of his family home: squabbling sisters, strict, irritable father, and diffident, fearful mother. We read in Young Phillip Maddison of his many exciting excursions out to his ‘preserves’ (the local estates that he had, with considerable enterprise, obtained permits to visit). The highlight of the cycling tales is the hair-raising (actually ‘hair-flattening’!) fraught swoop down the steep slope of the North Downs to Squerries Park in Westerham, which HW called in his 1913 diary in schoolboy code, ‘Easterbacon’.

This event was recorded in a school exercise book, one of three in total, in which young Henry Williamson, then aged 17, wrote up a record of his daily life at that time. Ostensibly it was a record of visits to his ‘preserves’ to collect birds’ eggs and generally explore the natural life of the local estates owned by aristocracy and landed gentry. This ‘A Schoolboy’s Diary’ was printed verbatim in the revised illustrated edition of The Lone Swallows (1933). We read in the entry for 1 March:

I went in the afternoon to a place near that awful hill where Tom and I rushed down on our cycles 3 years ago, at 40–60 m.p.h.

It is not until the fourth volume of the Chronicle, How Dear is Life, that we hear further details of this adventure. Phillip has started work in the autumn of 1913 at the Moon Fire Office (real life Sun Insurance), and is discussing his leisure time with two senior colleagues, who are teasingly quizzing him.

‘This afternoon I am going past the Salt Box, beyond Reynard’s Common, and I shall either go down into the valley below Biggin Hill, and look for woodpeckers in the beeches there, or continue onwards into Westerham, where I have permission from the châtelaine to roam all over the estate, and to fish after hay-cutting . . .

‘The first time I and my friend Desmond biked to Westerham, a year ago, we didn’t know what was coming, as we free-wheeled faster and faster, until we came to a right-hand bend too late to stop. I was in front, slewing about in the thick dust, and knew it would be fatal to put on the brakes. I had no idea it was such a dangerous hill, until I saw the country laid out below me like a sort of map. Golly, I went faster and faster, feeling like a bony skeleton out of the chalk suddenly fixed on a bike! I couldn’t steer, only hold the shuddering handlebars rigid and pray that the wheel spokes wouldn’t bust. I felt I had no hair, only a skull. The bike felt thin as a knife rushing down a white furrow of dust. You may not believe it, but my eye-lashes were actually turned in upon my eyeballs. Near the bottom, by some farm buildings, I saw a crossroads. Phew! If a cart had appeared —! I reckon I was doing quite sixty miles an hour by that time!’

*************************

However, there was an even more important influence on young Henry Williamson. His father’s brother, Henry Joseph Williamson, was a purser in the Merchant Navy and as such was urbane and successful. He is Hilary Maddison in the Chronicle novels, where we read in chapter 22 of Donkey Boy that he pays a visit to see his more hidebound brother Richard at the Moon Fire Insurance Company where Richard now works:

A motor car stood outside the Moon Fire Office, shaking with metallic heart-beats. It was painted blue, and lined-out in red, the colour of the russian leather upholstery of the high padded seats. . . . Two polished brass oil-lamps gave the panting monster a look of the East. Richard thought of Aladdin’s lamp.

Hilary tells him the car is:

‘An improved model of Panhard et Levassor, with poppet valve and a grilled-tube radiator! She’s a continental of course, and absolutely reliable.'

I have found a photo of this famous French motorcar on the internet in those exact colours – and a grand beast it looks:

There is a famous photograph of the Prince of Wales (the future King George V) being taken for a ride in a similar model. The driver, the Hon. Charles Rolls (who, in 1904, went into partnership with Henry Royce to sell the cars that Royce was building), was also a pioneer aviator and lost his life in a flying accident in 1910.

Rather ironically, the car used a German Daimler engine, for which the French firm had obtained a licence. The Royal Family continued for many years to use British Daimler cars, manufactured in Coventry.

Hilary takes his brother off for a ride and dinner (over several pages), and the nervous Richard is gradually won over to the merits of this modern mode of transport. But more importantly, the next day Hilary offers to take his young nephew for a drive. We learn that this is immediately before Phillip’s (so HW’s) ninth birthday – therefore the year will have been 1904.

Phillip remembered the ride in the blue and red motor-car all his life, the chequered hammercloth round his knees like a real coachman. Uncle Hilary took him down through Randiswell [Ladywell], where he dared to wave as he passed Helena Rolls, feeling a wonderful happiness as she waved back, and on to the High Street.

Again, the episode goes on for several pages, and there are several further references to this spectacular vehicle – but it is that first phrase, ‘Phillip remembered the ride . . . all his life’ that is so striking: young Henry was hooked on quality motoring!

Very early in the next volume, Young Phillip Maddison, we learn that Phillip is keeping a list of the cars he has seen. The collection of motor-car numbers was a current craze among young lads, but Phillip also includes further details which makes his list interesting reading as a historic record of what could be seen on the road at that time:

*************************

Go to:

LAP 2: Two wheels plus an engine (Nortons)

LAP 3: Four wheels (Peugeot to Alvis Silver Eagle, via Auto Union)

Appendices: The Alvis Silver Eagle (photographs); and Adventures with Alvis Silver Eagle DR6084, by Alex and Elspeth Marsh

LAP 4: Moving up a gear (Aston Martin to MG Magnette)

Appendices: Tale of a Two Litre; and Aston Martin Statement

LAP 5: The car that never was (Bédélia)

*************************