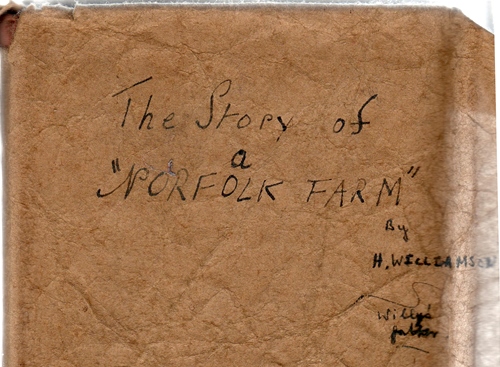

THE STORY OF A NORFOLK FARM

|

|

| First edition, Faber, 1941 | |

|

|

|

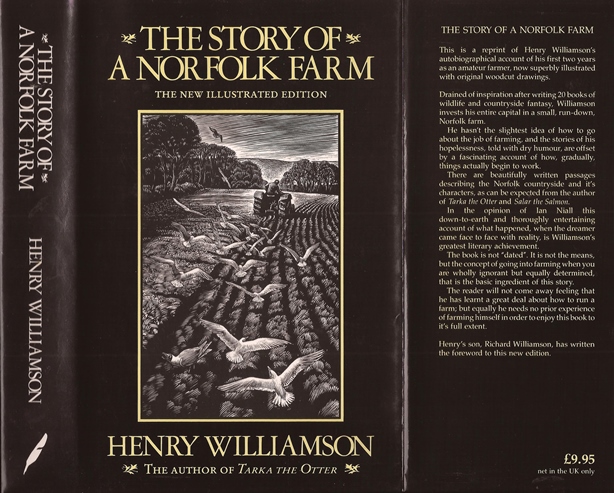

New edition, Clive Holloway Books, 1986 |

|

Appendix A: The missing material

Appendix B: Other ‘Norfolk Farm’ writings

'Immortal Corn': a proposed film, 1940

Life on the Norfolk Farm: a photographic essay

First published Faber & Faber, February 1941 (10s 6d)

(Although HW’s diary records on Thursday, 23 January: ‘The Story of Norfolk Farm published today.’)

Illustrated with 11 photographs by HW

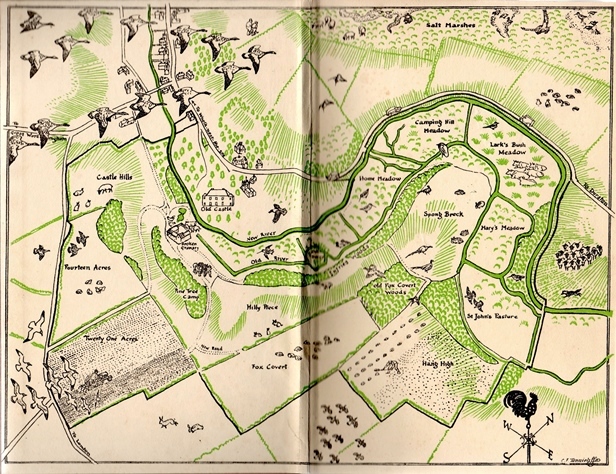

End paper maps by Charles F. Tunnicliffe

Faber, 2nd impression, March 1941

Faber, 3rd impression, November 1941

(Matthews, Henry Williamson: A Bibliography (2004), calls this the second text – with a small revision of two words on p. 302)

Readers Union, 1942, reprint of the second text, but with further small alterations and the medieval spelling of the word ‘plow’ changed to ‘plough’ throughout. Not illustrated.

Faber, 4th impression, 1943

Faber, 5th impression, 1944

Faber, 6th impression, 1945

Faber, 7th impression, January 1946

Faber, 8th impression, February 1948

Clive Holloway Books, new edition, 1986 (£9.95)

Introduction by Richard Williamson (one of HW’s sons, himself a naturalist and writer)

Illustrated with Frontispiece, vignettes and 16 full-page woodcuts by Christopher Wormell (these woodcuts were prepared from HW’s own photographs supplied by the HW Literary Estate)

Endpaper maps are signed by Wormell, but based heavily on the original Tunnicliffe maps

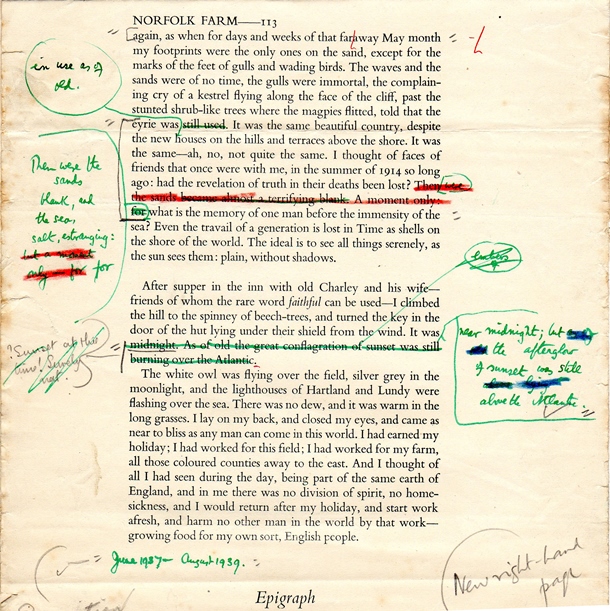

The title-page epigraphs obscure somewhat HW’s deep-set feelings about the place of agriculture as the back-bone of England/Great Britain. Agriculture is a main theme running through all his writing, from his very first book: The Beautiful Years (1921) has farming as its setting, while the fictional Maddison family are given farming roots; the regular reader will be aware of the many farming threads running through the content of all of HW’s books. Now, when writing about his actual experiences of farming, the quotations here seem a little vague. Farming was in deep depression at the time he became a farmer, and everyone he spoke to was against his proposed venture – hence the ‘British Everyman’ label; while the Mosley quotation carries a rather chilling warning masked within an inducement: do or die. Mosley himself came from a farming background (his grandfather, who more or less brought him up, was a great agriculturist, famed for stockbreeding and a prototype for the famous English symbol of ‘John Bull’), and after his experiences in the First World War, had agriculture as a central policy of his party’s manifesto. In wartime, agriculture became of even more vital importance. Nobody reading The Story of a Norfolk Farm can fail to see the importance of agriculture in HW’s thinking.

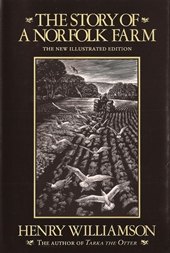

HW’s dedication, ‘To All Who Have Worked and Suffered for the Land and the People of Greater Britain’, echoes not only this theme but also his earlier dedication of the one-volume edition of The Flax of Dream (1936): ‘To All who fought for Freedom in the World War, and who are still fighting’. War and the plight of agriculture are two twists of one rope in HW’s thinking. This association is borne out by HW’s manuscript additions to his Frontispiece photograph in two separate copies of the book.

|

|

|

|

I died in Flanders – I am the unknown soldier – I died for ideals which were not of the market place – my voice is gone, but not my ghost – |

"All the poet can do today is to warn!" Wilfred Owen 1917 |

It is very evident that the onset of a second world war threw HW back into the turmoil and effects of the 1914‒18 war. The strain of that, coupled to the strain of the work on the farm, kept him in a state of extreme nervous tension throughout the period of the war, to the point of constantly being on the verge of breakdown. He tried (even if not consciously) to run the farm like a military operation, and this must surely have been reinforced by once again having to deal with horses, as he had when a transport officer with the Machine Gun Corps in the First World War.

HW indicates in an ‘Author’s Note’ (dated 11 November 1940) that he was advised to remove ‘certain passages’ from the book. The inference is that these passages contained political matter, and that to include them at that time would have been misunderstood and detrimental to the actual story of the farm. It is, however, a rather unnecessary statement, and gives a slightly off-putting, even sour note to the book. One wonders that the publishers, having advised that the material should be removed, should then allow their author to make such a statement – but no doubt HW insisted! However, as HW predicts here, the deleted material was included in due course, twenty years after the end of the Second World War, in the farm volumes of A Chronicle of Ancient Sunlight, where they have an interesting socio-historical significance. A bound copy of early proofs reveals exactly what was removed. This is discussed in Appendix A: it all seems pretty innocuous so many years later.

*************************

The Story of a Norfolk Farm is written in the first person in an objective style. His immediate family are given their real names, but most of the other characters have pseudonyms (real names will be given within the text here, within parentheses). Despite all the difficulties it portrays, it is a compelling and indeed fascinating story of HW’s first years at the farm. He takes his reader through all the processes and vicissitudes (to echo his sub-title from The Patriot’s Progress and following the ‘war/agriculture’ theme) that he, and all those connected with the farm, had been through; and the reader experiences it all with him. Reading it one knows exactly what life on the Norfolk Farm was like.

HW uses throughout the medieval (NOT American, as some have suggested) spelling of ‘plow’ for ‘plough’. This is not just idiosyncratic, but points to the well-known use of that spelling in the great fourteenth-century allegorical poem The Vision of Piers Plowman (1360s) by William Langland (c. 1330-1400). This poem is a series of narratives that show the corrupt state of the world and an attempt to remedy it by creating an ideal society, in which individuals pertain to the common good. Piers Plowman, a humble servant of God, tries to organise society into an ideal structure epitomised as ‘Ploughing of the Half Acre’. The underlying theme, or allegory, shows the ideal progression of a Christian soul. Thus one is also in the same concept realm as Bunyan’s Pilgrim’s Progress – bringing us back to HW’s The Patriot’s Progress. There also has to be taken into account within this same thought process The Georgics of Virgil (70-19BC), which discusses the conditions of life in the countryside under Augustus Caesar and various aspects of farming and husbandry. This contains the almost frighteningly percipient stanza (remember, written 2000 years earlier):

. . . there’s so much war in the world,

Evil has so many faces, the plough so little

Honour, the labourers are taken, the fields untended

And the curving sickle is beaten into the sword that yields not.

There the east is in arms, here Germany marches:

Neighbour cities, breaking their treaties, attack each other:

The wicked War-God runs amok through all the world.

Georgics, Book I, lines 505-11

(From the translation by C. Day Lewis: there is a copy in HW’s archive.)

Although The Story of a Norfolk Farm is in itself independent of these concepts and can be read for its own merit as a book telling the struggle of one (very inexperienced) man trying to learn how to farm at a very difficult time, it is nevertheless an important aspect underlying the work, and should be kept in mind as revealing the deeper layers of meaning hidden within HW’s writing.

*************************

The background and the narrative told within The Story of a Norfolk Farm are so closely intertwined that it is easier to follow this process as the book itself is discussed in the next section.

The actual writing of the book took place at the end of 1939. Since the beginning of November HW’s wife and the younger children had gone to stay with Robin Hibbert (‘Sam’ in the book), who was living and working in Bedford. HW had engaged a couple, Freddy Tranter and Mrs Hurt, to work on the farm and do the housekeeping – although this would turn out to be a disaster. On 15 December HW drove to Bedford, taking Margaret and Windles to spend Christmas there, leaving the Tranters, as HW termed the couple, in charge. On 17 December he continued his journey onwards to stay with Ann Thomas at Chippenham, noting that he lunched with Robert Donat, the actor, at Wendover. The purpose of this trip is made obvious in his diary entry for the next day: ‘Writing the Farm book by day and very happy with Ann’. There are similar entries for most of the following days.

HW returned, again via Bedford, on 23 December, to the farm and the problem of the Tranters. Christmas was a depressed disaster, but he plodded on, recording on 27 December 1939: ‘Working hard on the Book & feeling very fagged.’ On 5 January, within a long tale of woe about the Tranters, he noted: ‘I am trying to write the story of the farm, while all the while this wretched uncertainty remains.’ They left on 11 January – ‘thank God’ – leaving considerable chaos behind them. (Their tale can be found in A Solitary War, vol. 13 of A Chronicle of Ancient Sunlight.)

There was then a very hard and long ‘freeze-up’ throughout the land (cuttings pasted into HW’s diary reveal that London had 25 degrees of frost and the Thames was frozen over). HW was struggling hard on the farm, and Windles (now left school and also working on the farm) was suffering badly from flu. On 7 February 1940 he noted: ‘Trying to work on “Story of Norfolk Farm”. Windles still ill . . .’

His ‘Epigraph’ at the end of the book is dated 13 June 1940. This is not quite right, for it was the following day, Friday 14th, that HW was arrested under Defence Regulation 18B and taken to Wells police station, where he spent the weekend:

The police at Wells were very kind . . . I wrote the farm story sitting on my narrow wood-plank bed.

There are virtually no entries actually about the book after that, until 23 January 1941 (when he was actually ill with pneumonia but kept getting up to see about farm issues):

“The Story of a Norfolk Farm” published today.

On 4 April 1941 HW noted in his diary:

The Norfolk Farm has sold 4000 copies at 10/6 & is reprinting 2000 copies. If it sells 10,000, the overdraft (£780 to date) will be cancelled.

That it sold well from the start is illustrated by this advertisement placed by Faber (in which newspaper is not known):

The contract for The Story of a Norfolk Farm had been signed on 2 September 1940. The royalty was 20% on 10/6d, that is, just over 2/- per copy: so a total of £420 on the 4,000 copies sold, with total of £630 on 6,000: and if 10,000, the total royalty would be £1,050. However, he had already received £200 advance on the original amount. As can be seen from the bibliographical details at the beginning of this entry, there was a further reprinting in November 1941, with a new edition the following year and subsequent reprints. It was a most successful book, and today is widely regarded as a minor classic of the genre.

*************************

The book itself is divided into four parts:

Part One, ASPIRATION, covers the period from the journey made after Christmas 1935 and over the New Year 1936 to stay with his friend (and best man at his wedding) and publisher Richard (Dick) de la Mare (the son of Walter de la Mare) at East Runton on the North Norfolk coast, which is when the farming project was conceived, to the moment that the Deeds of ‘Old Castle Farm’ (HW’s name here for Old Hall Farm, Stiffkey, North Norfolk) were signed on 22 August 1936 and the Norfolk Farm became legally his property.

Part Two, ANTICIPATION, opens with a visit made by HW and his wife Loetitia and their eldest son William (Bill, known as Windles) to the farm in August 1936, and the various preparations through to Michaelmas Day 1937, when he was able to take possession of the farm as its owner.

Part Three, PREPARATION, goes from October 1937 through the first months of real farming to July 1938 when HW received the bill for ‘Arbitrations’ (there is an explanation within the text!) – his diary records that as happening on 22 July 1938.

Part Four, REALIZATION, takes the story on from the day that harvest begins, 10 August 1938, through to August 1939, although 1939 is actually skipped over somewhat until he takes a holiday in his beloved field (his refuge) in North Devon at end of July/beginning of August.

EPIGRAPH – dated 13 June 1940. Since the end of the previous chapter (and the actual end of the book) war had been declared. Here HW sums up the state of farming and of the Norfolk Farm:

. . . while once again the ruined cornfields of the Somme lie under the smoke of bombardment; and where some of the children I, a young soldier of the World War, knew and walked and talked with, have fallen in battle.

(This again reinforces his concept of close association between agriculture and war.)

However, even in that dark moment of the war HW ends by looking forward in ringing prophetic tone to better times.

*************************

Part One, ASPIRATION

The book opens with the journey undertaken by HW in his Alvis Silver Eagle after Christmas 1935 to stay in London at the Barbarian Club (the Savage Club), his London base: ‘There was a sense of freedom in my car . . .’ The husband of the poetess mentioned on the first page who couldn’t understand HW’s love of fast cars is Wilfrid Meynell, husband to Alice, and the destitute poet they looked after was Francis Thompson – one of HW’s great influences. We read also of the early influences of Richard Jefferies and Edward Thomas, ‘killed at Vimy in 1917’. Now aged forty, HW looks back at his life. He is at a crisis point. The West Country no longer holds anything of interest for him. His friend and hero T. E. Lawrence is dead – and HW feels dead.

His depressed spirits are lifted by a phone call from his friend and publisher Dick de la Mare, who invites him to stay with them over the New Year at their cottage in East Runton on the North Norfolk coast. As HW drives there he remembers his first visit in 1912 when, aged 16½, he had rather nervously cycled there alone to join a family camping holiday. En route he had had his first encounter with an otter (seemingly at Dedham or Flatford Mill in Essex). On that holiday they were caught in the famous 1912 flood – there are still marker posts showing the height of that flood in Stiffkey and other villages along the coast.

Once in Dick’s cottage, ensconced in a chair with a whisky, he pours out his woes: these include a hint that he is aware that another war is inevitable:

Always in history wars had come out of this condition.

I am personally convinced, having pondered this for many years, that this was the real crux of his problems. Having recently visited Germany, and despite his enthusiasm for everything he had seen and been told, and with his absolute conviction that Hitler, as an ex-soldier like himself, would never go to war, he would have been only too aware that the international situation was dangerous. Into these thoughts he brings the plight of agriculture (white bread – cheap imported corn). It is all very subtle. We do not know exactly what was said that night, but the solution put forward by the de la Mares was more radical than just the answer to temporary low spirits (which Dick was well used to!).

Interestingly, in a broadcast made soon after the end of the war in 1947 (which has only been discovered in February 2020), HW actually stated, proving my own premise, that his reason for going into farming was because:

There was a slump in farming, which under conditions then prevailing, could only lead to war. . . . So I undertook, almost by instinct, a completely new life. . . . I thought I’d do my little bit on a piece of English land that was in a state of decadence.

|

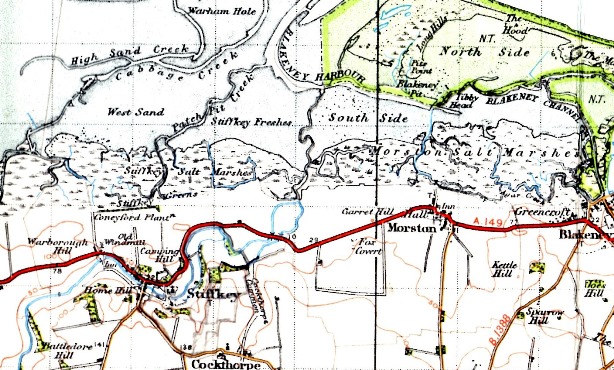

|

The section of upper map is from a contemporary Ordnance Survey map of the North Norfolk coast; the area around Stiffkey is enlarged in the lower map. Old Hall Farm was just south of the church and river at Stiffkey, with the land extending to the right. |

HW later drew a sketch map of the farm's fields as a guide for Charles Tunnicliffe, who drew the endpaper map for The Story of a Norfolk Farm (reproduced in the Book covers section):

The de la Mares suggest that he might like to live and farm in Norfolk, and they arrange to take him to see a property for sale, the ‘Old Castle at Creek’ (i.e. the Old Hall, Stiffkey). The next day they drive the few miles west along the coast to view this property, a manor house of the Elizabethan era, collecting the keys from the agent, Mr Stubberfield of Daplyn & Stubberfield (Mr Dewing of Andrews & Dewing, Wells-next-the-Sea, Norfolk). But HW dislikes the house, and knows he cannot live there.

However they make a second visit, and HW asks about the land, 242 acres (2½ acres = roughly 1 hectare – so total is about 100 hectares); to be told that it is in very poor condition. There is currently a tenant, Mr Sidney Strawless (Mr P. F. Stratton) – HW’s wonderfully expressive and apt name for this apparently rather spineless man. (There is, just north of Norwich, a small village by the name of Stratton Strawless, and there is a Stratton Strawless Hall. HW must have delighted in using 'Strawless' as a most appropriate pseudonym for Stratton!)

HW then makes a third visit on his own, during which he learns that Strawless also farms 1000 acres next to the Castle Farm. Very tempted by the farm land he ponders the situation. Back in London he talks to a Wiltshire farmer – very recognisably A. G. Street (well-known farmer and writer, remembered today for his best-selling book about his own farming experiences, Farmers Glory). While in London he visits his ailing mother in a nursing home at Blackheath, and remembers that he should inherit money from his grandfather’s Trust on her death.

Returning home to Devon he discusses the project with his wife, Loetitia, who offers the money she had recently inherited from her own family Trust on the death of her father in May 1935. But she feels that farming and writing might be too much for him. He suggests her brother Sam could come to help run it all. (This is Robin Hibbert, who was living in Australia at the time – not Africa as in the book. Another brother, Frank Hibbert was actually then living at Shallowford with the Williamsons. He had been looking after their father, Charles, until his death and was awaiting passage to join his brothers in Australia.)

All of which follows real life more or less exactly.

Chapter Five opens with philosophical thoughts about ‘Truth’, and HW reiterates here his thought that ‘charity’ and ‘clarity’ equate. His inner doubts about ‘Sam’ lead to a factual and objective description of the Hibbert family and the previous disastrous financial affairs of the three brothers. However, what he desires is the freedom to live his life in the manner he wants, which he states is essential to the creative artist. These thoughts lead him back to the ‘Great War’ which he considers arose ‘inevitably out of the repressions of European man’ and the need for someone to re-educate mankind against another such tragedy.

HW’s initial offer for the farmland is rejected. He reads farming journals and begins to learn farming jargon, and visits various other farms, none of which he finds satisfactory. He returns to Norfolk and sees Mr Stubberfield again. As he is returning home he decides to call on ‘a connection of Loetitia’s’ who lives at ‘Breckford’ (Thetford, Norfolk). Stopping at the inn there for tea, he overhears a conversation about farming, and so meets Miss Gunton, who manages (as a land agent) eleven thousand acres. (Miss Lucilla Reeve, agent for Lord Walsingham, owner of the Merton estate north of Thetford.) Asked her advice about the farm, she offers to meet him there the next day.

The ‘connection of Loetitia’s’ living at ‘Breckford’ was Sir Stephen Renshaw. The Renshaws had a house at Instow on the North Devon coast, but Sir Stephen’s address at this time was ‘Merton’, so presumably he was a tenant of Lord Walsingham. He was the father of Margot Renshaw (‘Melissa’ of A Chronicle of Ancient Sunlight). This, here unnamed, ‘connection’ advises against farming – his own land in Scotland has been requisitioned by the Government for munitions, while farming is in deep decline. (HW and his wife had taken a holiday on the Renshaw Scottish estate in September 1931.) Sir Stephen Renshaw is Lord Abeline in the Chronicle.)

The next day Miss Gunton also strongly advises against taking on such a derelict wilderness, but says that farming will soon once again become of foremost importance; and she is sure he intends to buy anyway, whatever she says!

The story of Lucilla Reeve is ultimately a tragic one. Apart from her farming duties, Miss Reeve wrote regularly for the Eastern Daily Press and Farmer’s Weekly. Soon after this meeting with HW she acted for Lord Walsingham over the sale of his farms – buying the final derelict farm, Bagmore, for herself, and by sheer hard work set it to rights. But in the early 1940s the whole area was requisitioned by the Government for military use, and all residents were forced to leave the area, on the promise of return after the war. This never happened (the area is still marked as a Military Training Area on current maps) – nor would they re-house those residents, even though Lucilla Reeve found a suitable property for herself and others to share. She valiantly fought this edict, but the effort eventually proved too much and she committed suicide in 1950. She records in the opening paragraph of her book The Earth No Longer Bare:

Bagmore Farm, Stanford, Thetford, 1939: Listening to Henry Williamson talking last night on the radio about the bare earth, I thought that perhaps his farming venture was not as interesting as my own. I did not hear him speak of any of the amusing sides of farming – he is probably saving them up for a new book! . . .

Lucilla Reeve was a member of the BUF from early days, as she agreed with the agricultural policy that was at the heart of the party. Although there are two letters from her in the literary archive, the only mention of her by HW is a cryptic diary entry for 16 July 1936: ‘Shot rabbits with Miss Reeve near Thetford.’

HW’s diary reveals (as recorded in Ann Thomas’s handwriting) that HW and herself made a visit to the ‘North’ from 29 January 1936. This was actually to the Lake District to get material for a proposed book (see the entry for Fergaunt the Fox), but they travelled first to Norfolk, staying in Norwich for three days. Although it is not recorded, presumably they visited the farm and sorted out further details, again visiting Norwich on the return journey.

With negotiations over the farm still in the balance, HW asks Miss Gunton to find a valuer for him: she suggests Richard Barkway (Edward Hawkins). A letter from Lucilla Reeve, dated 3 March 1936, opens:

Mr. Hawkins said he would wire you that Friday is a suitable day to meet you at Stiffkey . . . he will give you an honest opinion of the place.

Ann Thomas noted in the diary that HW went to London from 27 February to 7 March and evidently he went on to Norfolk during that time. The valuer’s opinion is depressing: the land is only actually worth £2,000, not the £3,000 asking price. However the owner drops down to £2,250 and an agreement to purchase is made. Ann Thomas noted in the diary, 9 March: ‘Stiffkey Agreement returned to Dewing.’

The legal side then had to be dealt with: the ‘Investigation of the Title’ etcetera was somewhat complicated and convoluted. HW found it all rather frustrating and irritating – but it is quite amusing to read!

(At the end of April a letter was sent to Robin Hibbert, explaining about the purchase of the farm and asking him to return to England and help run it; an extraordinary decision, as HW had not been able to get on with Loetitia’s brothers before they emigrated, and it is difficult to see how he thought that things would now be different.)

We read of attending a grass-drying exhibition by coke-furnace:

About this time there was an exhibition of grass-drying by coke-furnace on a farm north of Dartmoor. I went there and was surprised to find myself among at least a thousand farmers, who had come there in quite four hundred cars, most of them pretty smart cars, too. . . .

The idea was to cut the grass young, dry it over the hot blasts from the coke furnaces, then bale it, dry but green. Several cuts could be taken, and wet weather was an advantage.

But he is told this system won’t be suitable for the Eastern counties: lucerne is suggested instead (but he doesn’t know what lucerne is!).

This event is noted in an entry in a small pocket diary on 2 June 1936: ‘Grass drying, 2 p.m., at Buckland, Filleigh.’ Buckland is a tiny village just north of the Shallowford cottage at Filleigh.

HW’s diary for 15 July records that he visited the farm again, having travelled on after recording a BBC talk, staying the night with Stephen Renshaw at Merton and that he:

Met Edward Hawkins, Valuer, at Old Hall Farm, Stiffkey at noon. Raining but cleared later. Simply loved the place in sunlight.

The next day was when he ‘Shot rabbits with Miss Reeve near Thetford.’ He then drove down to Tenterden in Kent to meet Ann Thomas.

Eventually all is settled and we read:

Loetitia and I and the children were in the hut in the hilltop field, camping out and having a free time in the sunshine, when the Conveyance and Mortgage arrived . . . Outside a young man hovered – the usual staggart who was writing a book . . . – and he was called in to witness the signature . . . There, it was done.

I was the owner of Old Castle Farm!

Ann’s writing in one of the 1936 diaries records for 22 August:

Deeds & mortgage of Stiffkey Hall Farm signed, witnessed & returned to Wolfe Garrard.

Garrard, Wolfe, Gaze & Clarke were solicitors who had been recommended by Dick de la Mare: fictionalised in the book as ‘Mr Mordaunt Marjoribanks’ of ‘Messrs Gaythorne, Warble, Hogge & Hatry’. The witness was Guy Priest. (See Guy Priest, ‘Further Memories of Henry Williamson’, HWSJ 6, October 1982, pp. 12-19.)

That same day in HW’s personal diary is his first entry for that year:

Left Ox’s Cross, where family is on holiday, for Stiffkey. Windles, Gipsy and I in Alvis with small green tent & flea-bags. We stopped at Shallowford and bathed the next day.

Part Two, ANTICIPATION

HW tells us of the overall arrangements that had been made for actually taking over the farm (the tenant has to be given due notice etc). This has been agreed for Michaelmas 1937 – at this point fourteen months away. Very oddly, there is only one glancing mention of the owner’s name in HW’s personal papers: on a Memorandum page at the end of his 1936 diary he noted that the ‘General rate for Francis’ cottage to be paid by Capt. Gray until 25 March 1937’. At the beginning of this new section in the book, he slips in the word ‘Commander’, and in due course this becomes ‘Commander Trelawney’. A potted history of Old Hall (see HWSJ 40, September 2004, pp 70-71) reveals that in 1928 it had been left to a Mr D’Arcy Gray, who did not live in the Old Hall and was domiciled in Cornwall (hence HW’s fictional name ‘Trelawney’). It had become very dilapidated. Early owners were no less than Sir Nicholas Bacon, father of Francis Bacon and later Lord Townshend, the well-known ‘Turnip Townshend’. As HW now bought the farmland, so the Old Hall itself was bought by a wealthy business man and his wife, Mr and Mrs Cafferata; they are not named in The Story of a Norfolk Farm, but were to become good friends to the Williamson family.

HW now takes his reader on the journey across England made with his wife and eldest son to visit the Norfolk Farm. They called in to see his Bedfordshire relations at Aspley Guise, scene of HW’s childhood holidays with his cousins Marjorie and Charlie Boon (who was killed in the Somme in the First World War). HW’s mother had already told him that Marjorie and her husband, Frank Turney, have had to give up farming.

This was one of the happiest journeys of our joint lives. . . . We drove slowly along the top lane to the farm, through an ancient gate, and so to the pines on the Castle Hills, as the grassland was called in the Deeds. [See Pine Tree Camp on Tunnicliffe’s endpaper map.]

Through the trees, which grew along and down the slope above the farm buildings, we saw the meadows and beyond was the sea, only less pale than the sky. We lay down on the dry turf, and rested, at home on our own land.

|

|

Home Meadows from the pine trees in 1968 – a view very little changed from the photograph facing p.172 in the book (photo © 1968 John Gregory) |

In real life when they arrived, HW attended what is referred to as the ‘Morston farm property sale’. Not mentioned in the book, this was to do with his tenant P. F. Stratton, who, we have learned, also farmed (we are not told whether as owner or tenant) 1,000 acres adjoining the Norfolk Farm. HW’s diary relates, on 25 August:

We wandered over farm, loving it all. Then over the saltings and the lovely yellow sands, where we bathed. Windles floated on his back in quiet warm water. In evening we called to see the Shawcross’ who were dining with Major Hammond, a neighbour of ours. Found him truculent, outspoken, factual, interesting, and dictatorial. He asked me if I was going to get rid of Stratton, my tenant, who he said had helped to ruin Morston. I replied evasively and non-committally.

Major Hammond’s attitude was to prove a very real problem for HW in due course.

We read how, when they go to look at their new farmhouse – Walnut Tree Cottage – then occupied by the gardener to the ‘Old Castle’, they met Napoleon and his wife ‘Lady Norwich’ as this rather eccentric (mad) old woman styled herself (in real life Mr and Mrs Francis). They get a very tetchy reception, and the old lady trains a gun on them from an upstairs window.

However, they are given a very nice tea and welcome by Mrs Hammet, who lives next door (a Mrs Sutton, though she was not connected to the Suttons who were to work on the farm). Afterwards they stroll down to the sea:

We sat down on the grass, gazing out over the marshes, one vast gut-channered prairie of pale blue sea-lavender. Afar was the sea merging in summer mist and the palest azure sky. . . . This was the sun I remembered from boyhood days, the ancient harvest sunshine of that perished time when the earth was fresh and summer seemed an illimitable shining that would never end, . . . and sitting there it was as though the past and present were one again, and I had entered upon my heritage of happiness.

The book describes how they wander around, eat supper in the Anchor Inn (still there today) and attend a regatta at the unnamed but unmistakably well-known resort of nearby Blakeney.

For six days we camped under the pine-tree, walking about the farm, getting to know the fields and the meadows. The grassy hills were bleached by the sun, and had no bit e in them. . . . Thistles made the hills ragged. The barley was brown with docks on one field, grey with thistles on another. Nothing on the farm was pleasing except its views.

However, HW remains optimistic, thinking his hard work will soon sort everything out. They leave (after dealing with a problem with the Alvis) on 27 August, so although away for six days, they were only actually at the Norfolk Farm for three days. Not recorded in the book, they again called on the Boons very late in the evening, and the next day continued on to Swindon, where they ‘bathed in Jefferies’ lake at Coate’ (HW was heavily involved with editing Richard Jefferies’ work at that time – see the ‘Life’s Work’ entry for Richard Jefferies), returning to Shallowford late that evening.

Diary entry, 3 September 1936:

This day the sale of Hall Farm was completed. Francis’ cottage to be vacant at Midsummer, 1937.

Throughout this whole period HW was busy with regular BBC broadcasts, articles, and preparing himself for farming work. But, with the sale completed, problems soon began to emerge: mainly the very considerable legal complexities to do with ‘dilapidations’ (the sum charged against an incumbent for wear and tear during his tenancy), further complicated by the fact that Mr Strawless (P. F. Stratton) had made a Deed of Assignment to his creditors: that is, he declared himself bankrupt, thus making everything very difficult indeed. To add to these complications we learn that Mr Stubberfield (G. E. Dewing) – agent for the sale of the farm – is now a trustee on behalf of the bankrupt Strawless: a conflict of interest that was not to be in HW’s favour. This is further complicated by the fact that Strawless’s trustees appoint him as bailiff to the farm – and so instead of leaving immediately he will now stay on until the following October. Again, all the problems are interesting and often amusing to read; but they made a continual strain for HW to deal with.

Sam (Robin Hibbert) is on his way back to England by boat and taking a postal course on farming as he journeys. A Will to cover the new circumstances of the ‘landed proprietor’ is drawn up – over-complicated for HW. Sam is to be trustee and executor in the event of HW’s death: ‘he [Sam] was tough now’.

Sam arrives – six hours earlier than expected, causing some annoyance to HW. (The fictional version is toned down considerably from the entry in his diary!) After a dinner of imported Argentinian beef (not approved by HW) washed down with liberal amount of Algerian wine, Sam tells of his life at the Cape (actually Australia). But – ‘He was the Sam of old . . . Sam wasn’t tough.’ HW, inevitably, already thinks he has made an error of judgement in calling ‘Sam’ back to help. But the very next day Sam sets to decorating and repairing the Shallowford cottage, to save on their own dilapidation costs in due course.

At the beginning of January 1937 HW attended a Farm Mechanization conference at Oxford (for which he noted he paid £3), which he greatly enjoyed, quickly establishing himself as a ‘personality’. But, going on to London to meet up with Ann Thomas, he was precipitated into a crisis: Ann informed him that she planned to marry someone else. HW was thrown into turmoil. Neither episode is mentioned in The Story of a Norfolk Farm, but that this was a huge emotional trauma is seen in his anguished diary entries over many months.

Letters continually arrive from Mr Barkway with problems, or rather matters needing attention. Apart from the question of repairs that Strawless, or Stubberfield as his trustee, should make, HW had to approve the crop schedule for 1937, and realises how little he knows.

Tithes also have to be fathomed out. Tithes were a form of tax: a tenth of the profit of the land was given to the Church, as the body holding authority in any parish, originally to help the poor and needy but increasingly for the use of the Church itself. Non-payment was a summonable offence. In 1936 an Act of Parliament transferred this munificence to the Government instead: substantial redemptions could be claimed by farmers, but only by an official application to be submitted by March every year. (HW subsequently helped with, and wrote an ‘Epigraph’ for, George Gill’s A Fight Against Tithes, 1952.) Added to this were also Land Tax, Drainage Rates, Dilapidations, Tenants’ Rights, etcetera. HW’s diary contains many detailed entries concerning these matters, all stressful; but in The Story of a Norfolk Farm all is written in a light amusing and interesting style that carries the reader along.

Our would-be farmer realises that a lorry and trailer will be needed for transporting items from Devon to the farm and subsequently for actual farm work. HW delegates the responsibility for this to Sam. (One can almost see trouble looming!) The plan is that HW and Sam will go to camp on the farm in the summer and start work repairing and making up the farm roads prior to the official take-over at Michaelmas.

On another visit to Creek HW discovers three condemned cottages owned by Matthew Bugg for sale, and determines to buy them. These are the ‘Chapel Cottages’, which he had actually seen in early December 1936 (just before Robin returned), when he had asked ‘a village worthy, Mr. Gidney, to enquire for me of the owner. Later called on G. E. Dewing & asked him to value & try & arrange purchase for me.’ The contract for the cottages was signed on 9 February 1937.

|

|

Two of the 'Bugg Cottages' today, bearing a blue plaque marking HW's years here. Note the metal wall tie cut in the shape of an owl. (photos © 2008 John Gregory) |

|

|

On 20 March HW signed the contract for his next book Goodbye West Country, so he was working hard on that as well as dealing with all the ramifications surrounding the farm.

On this visit to the farm (as above) he found that ‘the Old Castle’ was being repaired and altered inside, especially the water-heating system.

The builders were making a fine job of it . . . tearing out the old wasteful heating furnace and putting in a new one with bronze pipes, fed by a water-softening plant which removed both chalk and carbonic acid from the water. . . . The old pipes were almost fossils, solid with lime.

(It might amuse readers to compare this with the story-line covering the same episode in The Phoenix Generation (1965, vol. 12 of the Chronicle), where wild Bill Kidd cleans out the boilers of ‘the Old Manor’ with his own recipe and manages to blow up the whole system!)

HW meets the owners, the Cafferatas, and sends a telegram to his wife to come up by train. She tells him that Sam has found a lorry. They dine with the Cafferatas. HW organises arrangements for the ‘Three Dilapidated Cottages’ (diary: ‘All damp, dark, and awfully depressing’). A builder named Bly (Shrive) offers his services. HW also organises the rental of a gravel pit, which will be used for remaking the farm roads.

HW’s diary for 3 May 1937 records:

Bought reconditioned 1932 Morris 2-tonner from Moor of S. Molton today for £66/10/-. Tipper, hoops & hood, engine, all new – rest made 100%. We have a 2-ton trailer (£21), this lorry, a £9 trailer, & caravan for our summer road-building campaign.

We read of the problems with the repairs to the lorry bought by Sam: HW is impatient as he wants to get off to ‘Creek’ and begin working. He is also worried about the cottages. Proving ‘Mr. Bugg’s’ legal ownership is complicated due to the many signatures of the original Chapel Trustees:

The legal procedure known as Investigating the Title was so scrupulously carried out by Mr. Mordaunt Marjoribanks that at one moment it looked almost as if some of the original ten chapel Elders who had put their marks, black inked crosses, on the deed [many] years ago might have to be exhumed by order of the home Office, to prove their legal title.

HW includes here, as Chapter Fourteen, a list of the solicitor’s costs!

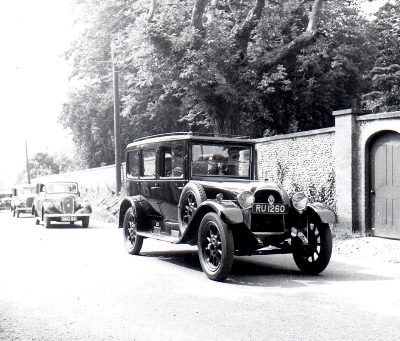

The lorry is ready at last (HW’s diary records all the complications and his frustrations in no uncertain terms!) and is loaded up in what was a far worse scenario than that actually recorded in the book. But it is still not functioning as it should and is sent back to have its brakes relined. Then:

At 2.30 p.m. on Friday, the 21st May 1937 our column left for Norfolk:

HW in his Alvis towing the caravan, with Sam behind in the green lorry towing a loaded trailer.

We spent the first night near Swindon, with some friends and drank a bottle of champagne.

(The friends being Ann Thomas and her mother Helen living near Chippenham.) The journey to Norfolk was pretty awful. At Oxford they find the Morris Garage works and some further repairs are made: then travel onwards, with further complications. That night was spent on the road, and late into the night (around two o'clock in the morning):

we came to the dark silhouette of a group of buildings which turned out to be a gravel-washing and sifting plant. There was a concrete semi-circular entry and exit from and to the main road. It was an ideal parking place. We pulled in, made the beds in the caravan, and lay down to sleep.

|

|

|

The column at the gravel-washing plant the next morning, with the Silver Eagle towing the 'old pattern of caravan' (an Eccles), and the Morris lorry 'to which was attached the trailer, on which lay the dinghy covered by a green cloth'. The bearded 'Sam' stands by the lorry in the upper photograph. |

All these ‘French farce’ details are all exactly as it happened and recorded in HW’s diary. They finally arrived on Sunday at 7 p.m. and unloaded, again in turmoil. With difficulty they manoeuvre the caravan into place at ‘Pine Tree Camp’.

They immediately begin the back-breaking work of the road-building, become exhausted, and realise just how big the task will actually be. After a day or so they take on a man, ‘One-eyed Jarvis’ (William, or Billy, Jarvis) and by the end of the month another ‘young red-headed labourer’ (Norman Jordan). The work then continues more easily and after a while:

The yellow-white road crept up to the big corn barn, and round it, and past the cart-sheds and round the pond to the granary.

HW turns his attention to the problems of dealing with the uninhabitable Bugg Cottages: plans for renovations are ordered and tenders for work asked for: but these are excessively high.

HW then gives a vivid description of working to clear a lane ready to make up the chalky gravel road – in the heat amid a variety of flies: hundreds of black flies, irritating; then a ‘zoom’ of horseflies, fairly easily dealt with; then a wasp; but worst of all, that plague of cattle, a warble fly:

And what a fly! In outline it was almost an equilateral triangle, with innocent-looking black wings, laced with gold, and a yellow-brown body touched also with black. Its battery of eyes had the glaze of bright pottery in the windows of seaside shops . . . [and] a fearsome beak or proboscis . . .’

Just as he was about to kill it a sand-wasp snatches it off his skin and expertly deals with it.

After that, the sight of Hawker Fury planes passing overhead was a tame mechanical thing.

(There have been earlier references to aeroplanes at a nearby airfield: a little frisson of future activity.)

The dilapidated cottages continue to be a problem, while the old gardener, Napoleon, plus his wife, refuse to leave Walnut Tree Cottage, earmarked by HW for the family farmhouse. HW and Sam decide that the only solution is for them to do the work themselves, although that means foregoing a government grant.

HW sets off ‘one July evening’ for ‘Romney Marsh country’ to fetch his friend and secretary (Ann Thomas, from Tenterden, Kent, on 16 June). Ann’s sister and her son had mumps but Ann assured HW she herself was now out of quarantine. (To clarify the background here: Ann & HW’s daughter, Rosemary, was with her grandmother at Chippenham, but was to join Loetitia and the Williamson children in Devon for the summer.) On the night they return it pours with rain and Ann, sleeping under an awning attached to the caravan, gets soaked. The next day she goes down with mumps. HW (understandably) is extremely agitated that this will put paid to his work schedule. Ann is banned to a tent placed well away for six weeks and her food is pushed to her on a pole!

Work now begins on the cottage renovations, amid every possible problem. HW’s account in the book is quite restrained and amusing compared with that in his diary!

HW made two journeys to Devon during August to collect loads of household effects, taking the lorry and trailer: both journeys are French-farce hilarious to read; but extremely difficult to endure at the time. Shallowford was due to be vacated at Michaelmas, 29 September. With nowhere ready for the family to live, it had been arranged that Loetitia and the children would lodge in the meantime with ‘the children’s old nurse’ (Annie Rawle).

For a final journey to collect Shallowford effects HW hired a carrier from Whelk (Bert Perkins) for the heaviest work, while he travelled down in the Alvis and took residue material to be stored in the field at Ox’s Cross.

He does not record in The Story of a Norfolk Farm that on 27 September he sat in an empty Shallowford cottage and wrote an article for the Daily Express, ‘Goodbye West Country’, a most poignant piece which is collected, with his other Express articles of the period, in Chronicles of a Norfolk Farmer (HWS, 2004; e-book 2013). Neither does he record in the book that, on leaving Devon, he left his trailer at Helen Thomas’ home near Swindon and then travelled in the Alvis across to Petersfield on the Sussex/Hampshire border (presumably with Helen and Ann) to attend the unveiling of a Memorial Sarsen Stone to Edward Thomas, placed at the head of the shoulder of Mutton valley at Steep, where he had lived with Helen when alive. It was from here that Thomas left to go to France in the spring of 1917; he was killed by a shell on 9 April, the opening day of the Battle of Arras. HW notes meeting there John Masefield, Walter de la Mare, H. W. Nevinson, and various members of the Thomas family. Afterwards he returned to Swindon, retrieved his trailer, and returned to the Norfolk farm.

On his return to Norfolk he found that the work on the cottages was not going according to plan. Again the account here is quite restrained compared with his diary entries. Sam had been in charge – and the fact that a short time after this he left to take a job ‘in the Midlands’ should tell the reader quite a lot! HW no longer had a farm manager. He now abandons Pine Tree Camp and transfers to living in the farm granary, with the Shallowford effects piled up all around him. So begins a new phase.

Part Three, PREPARATION

The opening chapter is titled: ‘I am a Melancholy Farmer’.

On Old Michaelmas Day 1937 I became a farmer. [The date was 11 October.] At noon on that day the bankrupt tenant went out, and I was the ingoing man. At one minute past noon, I was the occupier of my own farm of 235 acres.

To celebrate he took a walk round the farm boundary, mainly seeing all the problems involved and his ignorance of farm methods – tractors, horses, sheep.

Here were the fruits of years of neglect. I felt like a soldier before zero hour.

On his return his spirits are cheered: ‘Ann had a cup of tea waiting for me’ next to the granary stove with a ‘pipe that went up through the loft’. His diary records that on 11 October (this day) he had ‘cemented and fixed a stove-pipe through the first floor and up through the roof of the barn’, with the help of a long ladder. Even so, penetrating wind, rain and sleet did not make for comfortable living.

It is not recorded here, but HW noted in his diary that on 5 October he had finally received the money due from his mother’s estate, ‘about £1,760’ which must have solved immediate financial difficulties.

HW takes on a steward, or manager, Bob (Sutton), and also his father Jimmy (Sutton). There is an auction of the effects of the bankrupt ex-tenant, Strawless, and he instructs Bob over his strategy for buying various items that he wants. This inevitably ends up with Bob paying more than instructed and bidding for several extra items! Incidentally, Bob tells him that Strawless hadn’t lost his money through farming, but by frequent (and expensive) shooting trips to Scotland and racing small boats in the summer!

HW now records the visit paid to him by Lady Sunne (Dowager Lady Dorothy Downe), who asks him to join their movement which needs the help of

all men of good will, the land neglected, labourers leaving the land . . .

Lady Downe was the very active local leader of Sir Oswald Mosley’s BUF. HW shows here quite clearly that it is Mosley’s policy on agriculture which attracts him, although he also shows that he realises that joining the BUF will make personal problems:

I would put more into farming than I would get out of it . . . Personal loss would come if it were known I had joined this political party. . . . Britain needed new leadership, otherwise the future would only hold disaster. The present system was ruining the land and the people . . . A nation that neglected its soil, neglected its soul; and the people would perish. . . . We came from the soil, the earth bore and shaped us; we returned to the earth, after each man his journey.

HW next describes life in the farm granary, which includes queen wasps, mice, death-watch beetles, and outside ducks, pheasants, stars and hoodie crows – or ‘denchmen’ as they were called locally (dench = Danish) – and other migrants from Scandinavia: a tiny fire-crest wren and three barn owls, all exhausted.

Day after day of windless calm of sunlight, serene and warm, as though all life were suspended on the earth, save for the movement of wave and tide, and the fluttering and piping cries of wild birds.

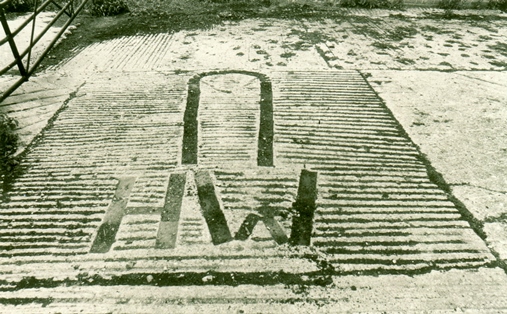

He does not record, as his diary reveals, that on 11 November he put into place his owl icon:

We finished the concrete slab by bullock yards today. I set my owl and initials in red brick on the junction slab.

|

|

Taken soon after the bricks were set, with a light covering of snow, looking towards the farm entrance |

|

|

Today, the owl and HW's intitials are still there, the bricks partly eroded by weather and time, and grown with moss (photo © 2008 John Gregory) |

HW includes a ‘Disturbance’ statement sent by Mr Stubberfield on behalf of Strawless (born out by his diary entry). The all-important ‘Valuation Day’ takes place on 21 October.

The cars of the Valuers were drawn up outside the corn barn when I got there. Mr. Stubberfield [Dewing, there on behalf of ‘Strawless’] had a new car, nearly as smart as Mr. Barkway’s [Edward Hawkins, on behalf of HW].

They walk round the farm examining various details of dung-heaps, hayricks, and soil content for manure residue! Again, amusing to read, but a very stressful occasion for HW, and it is only too obvious that he is going to lose out.

He is also continually coming up against the ‘old-ways’ attitudes of his two workmen, who fundamentally object to his ‘new-fangled’ ideas and methods: ‘No-one else does that.’ ‘We wun’t be in no muddle.’ ‘You’ll larn, guv’nor, you’ll larn.’ HW tried to run the farm like a military operation: he was baulked at nearly every turn. It must have been incredibly frustrating to an ex-army officer used to every order being instantly obeyed without question!

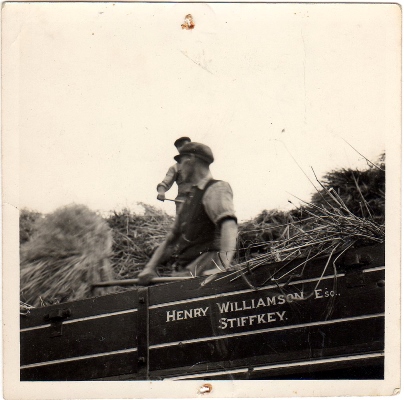

HW attended several auctions at this time, buying in equipment and stock for the farm, again all related with interesting and often amusing details. He buys two horses, Blossom, a mare, for ‘thirty and a half guineas’, and Gilbert, a ‘black gelding, thin and ragged as an old crow’ which Bob takes a fancy to: ‘Blast, I like him.’ Gilbert cost twenty-eight guineas. He also ordered a Ferguson tractor and acquired two new tumbrils:

They looked to be splendid vehicles, shining with varnish over their red and green paint, my name and village in white letters on their side. Their fine new rubber wheels would halve the back-breaking labour of horses on the hilly land.

Strawless’ harvest has to be threshed – the difficulties immense. The new Ferguson tractor does not arrive as expected. Heavy rain makes carting water from the well up the steep slopes with horses even more difficult. Everything that could go wrong does. But somehow all is achieved.

Three days later the threshing was done. . . . On the fourth morning I went to the station in the lorry with Bob to fetch the new tractor. At the station I sent a telegram to Devon, telling the family to come up two or three days before Christmas. We would all live in the granary. . . .

He analyses the cost of the cottages to date: ‘Bugg Houses had become Williamson’s Folly.’

HW gives a detailed description of his new Ferguson tractor and its powers. He puts it to immediate use to plow up very steep Hilly Piece.

It was twilight when I got to the field. . . . The little machine went up without the least falter. Its thin spiky wheels pressed the ground lighter than horse-hoofs would have done. Its twin shares bit into the sullen soil and turned it over, exposing a tangle of white roots. I heard Bob mutter: ‘Blast, I like that patent.’

|

|

HW plowing with the 'little old grey dicker' (photo © John Fursdon) |

Two days later the Ferguson is also used to plow in the mangold tops on Fourteen Acres, and HW has the thrill of gulls following his plow – and photographed it. But he remembers that the family are due to arrive at Whelk Station (Wells-next-the-Sea), and rushes off to meet them in the Alvis with trailer for luggage.

Hark! What’s that? A strange jangling, honking, crinkling noise, hundreds of noises all together, high up in the sky. Listen, children! The wild geese coming in from the sea! This is the Coast of the Wild Geese!

All are to be together in the granary – Ann having aired sleeping bags by the stove.

How the children loved the granary. They ran up and down the stairs, they explored all the dark nooks and caves among the stacked furniture, ever so much nicer than an ordinary house . . . I knew I was right to have brought them here to the farm.

The family actually arrived on Thursday, 16 December. HW’s diary records: ‘Gipsy & family came from Devon. Cottages not ready, so all come in this granary. Rather a noise & chaos.’ On 21 December they moved into Cottage no. 3, still unfinished, damp, and the stove not working properly. HW remained in the granary until the New Year.

Christmas Eve, 1937

The frost glitters in the starlit grasses; the horse pond is frozen; wild geese fly overhead. When I open the granary door, I see bare trees against the sky. It is Christmas again, and I have a rendezvous in ancient moonlight, with you and you, and you, unknown comrades of that first Christmas . . . A long time ago, Christmas 1914. Yet we still hope, those who were there – the living and the dead – that the vision of peace we lived during those few rare hours may be made real and everlasting.

He tells in this chapter the story of the 1914 Christmas Truce. It is powerful and moving writing, and was first published in the Daily Express on Christmas Eve, Friday, 24 December 1937, with the title ‘They Saw the Same Star Rising . . .’ The chapter ends:

The wild geese cry as they pass high under the moon, flying for the clover fields, my little children stir in their sleep. The morning star of Hope is rising once again.

So the work continues: order gradually being imposed over chaos. We read of buying ‘some good Aberdeen-Angus bullocks’ from Ireland, via a farm association so he wouldn’t be ‘done’. His diary reveals this was the ‘C.G.A. – Country Gentleman’s Association’ (who provided the imposing black ‘Estate Book and Diary’ volumes with their huge amounts of information, legal and practical, of these farm years in the archive), where he details the purchase of the bullocks, as in the book.

However, driving them home, ‘they moved slowly, being excessively thin’: they then scour, and neither Bob nor Billy will listen to his ideas about their feed. Eventually HW calls in the vet, whose advice is the same as HW’s own proposed regime. Buying through the C.G.A. had been of no benefit whatsoever – he was still ‘done’.

HW reproduces a copy of a report on the farm made by an official of the Norfolk Agricultural Station in July 1937. It makes an interesting read, even for a non-farmer. HW’s diary for 22 July 1937:

Mr. Cock, agricultural advisor, came. We decided the schedule for cropping for 1938. He said the arable wasn’t too bad. . . .

It was apparently against his advice that HW bought the ten bullocks (he had recommended heifers):

If I had a fixed idea, I had to set it to work; I was built that way.

HW knew his own faults only too well!

Pullets (young chickens) bought in autumn 1937 had done well and had laid over 600 eggs by Christmas. So he decided to buy ‘four turkey poults and one stag bird’ – noted in his diary on 22 March 1938.

Then follows a tale of buying seed barley: that the chapter is headed ‘All is Experience’ will alert the reader that it involves yet more problems. Next, the drilling of oats on part of Twenty-one Acre field: Bob leaves off and HW, worried that the rooks will take the seed unless it is harrowed in, hitches the harrow onto the Silver Eagle Alvis. Designed for speed and not heavy work it quickly boils and he has to keep stopping to let it cool down.

‘Yer’ll larn’, croaks an old rook.

Then it was the turn of the barley, a buoyant chapter – like the landscape he describes: ‘At last I was sowing my own corn!’ He tells how the men broadcast fertiliser and seed the old way, by hand. His diary (Saturday, 26 March 1938) again corroborating every detail. Then ‘I, with Gypsy, & Bob Sutton, drilled & harrowed in afternoon. Bob quit at 4, we two drilled until 6 p.m.’. On the Monday Ann and he finished the job. Despite all this effort he found the rooks busily feeding on the seed:

‘Yer’ll larn! Yer’ll larn!’

The next chapter describes a typical day’s work or, rather, a lurch from crisis to crisis: a sick bullock, the rolling of Twenty-one Acres overrun with moles loosening the soil . . . He remembers the well is due to be cleaned that day with a history of its previous mismanagement by the blacksmith brothers, and rushes off to sort that out. Plowing ensues. Little Margaret (now aged eight) brings his lunch bag and the day’s post, most of which gets thrown into a furrow (that may be author’s licence!) More plowing – put everything away – home for high tea, where he then hears that the in-calf heifers and yearling bullocks from Ireland would arrive at Whelk at 8.30 p.m. Loetitia drives them in and they walk the beasts home in the dark: HW in front with lantern to warn oncoming motorists and Bob behind. Many field gates have been left open so beasts go into fields and have to be chased out again. A car runs into them: no brakes; graphic description here, some animals appear injured, others possibly missing. Eventually they get back to the farm, all present and little actual injury. All of which is borne out in a diary entry 25 March, which begins ‘A long day today . . .’ with a further diary entry for 13 April:

The Norwich Union Ins. Coy. have the impertinence to say my cows damaged their Insured’s car in recent smash, & they are charging me for the repairs!

(Norwich Union was once the standard insurance company in the area – in more recent years it has become the huge international conglomerate Aviva.)

There has been a drought for weeks and the land too hard to plow, a constant worry for HW: he records it as actually ending on 25 March – but in the book he is jumping about within time sequences to give his tale better subject coherence. At last they get on and sow the barley on steep Hilly Piece. Then he sets up a ‘malkin’ (an old word for a scarecrow) to try and protect the fragile nest of a plover which they have so carefully avoided during their own work. The malkin is too realistic, bringing back memories of the Somme:

Its paper face was bleached with the sun; and whenever I had seen it, suddenly, as I had been rolling the Hang High field, it had given me a start. The legs were rounded, as though swelled. It looked like something that had died in that position, in a warning attitude, its arms spread out, its shattered head thrown back

A photograph of this malkin was used as the frontispiece for the book.

Although tempted to take the rest of the afternoon off he continues work, rolling the barley in Fourteen Acres and feeling all was well.

I was a farmer. All my corn was sown. . . . I found myself singing at my good fortune to be a farmer, and the owner of such a beautiful farm. In that moment dream and reality were one.

With the end of the drought HW remembers again the tempest of his childhood holiday in 1912, which flooded the whole area, while even part of Norwich was under water. The men get on with indoor jobs and HW goes to London to do a broadcast. At this time he began a new series of BBC broadcasts, which together with his articles brought in much needed income for paying wages and other expenses. Thurs 28 April: ‘Broadcast to Empire 7.10-7.25. Motor’d to Norwich & took noon train arriving 2.10 pm at Liverpool Street station.’ Again on 5 May and 26 May: ‘London. Daily Express, ‘When Will Salmon leap in London’s River’ & BBC Broadcast to Empire 7.10-7.25.’ (These items can all be found in the appropriate HWS publications.)

Signs of the national disquiet are subtly fed into the narrative:

The beautiful and desolate marshes, where the sea-lavender was coming to flower, were out of bounds . . . The barley fields beside the sea . . . were being ripped up for asphalt roads, bestrewn with heaps of wood and iron, while white lines of tents were already extended across them. An army training camp had sprung up.

The fish-and-chip hut (situated in the yard of ‘Bugg Cottages’) did a roaring trade, to the disquiet of the inhabitant of Bugg Cottages, exasperated by the soldiers throwing discarded newspaper wrapping over his wall. HW was filled with ‘Foreboding’. Farmland is being ruined. He cites Sir Henry Rider Haggard’s (1856-1925) book A Farmer’s Year (1899) as also crying out against the dereliction of farmland: ‘but then, as now, nobody cared’.

He mentions here that he spoke ‘at several meetings of the party I had joined’. There is no evidence of that in the archive (but see my comment further on). He did speak at a meeting that was on Armistice Day, 11 November 1938 – not quite the same thing:

Stayed at Hillington with Lady Downe & spoke at the Ex-Serviceman’s dinner there, in the great hall. A nice gathering, perhaps the last in the pre-war idiom in England.

We read now of the neighbour’s horse that fell into a dyke, which HW uses as an example of the state of agriculture, so much deteriorated from the time of Coke of Holkham: the famous Coke of Norfolk. (1764-1842, 1st Earl of Leicester, who inherited Holkham Hall, Norfolk and widely known as an agricultural reformer).

As HW expands these thoughts one can feel his deep anxiety about the situation, epitomised by his disquiet on finding the richly nutritious seaweed so munificently thrown up by a storm tide has, instead of being spread on the fields as once it would have been, merely been burnt – and that burning has engulfed the furze bushes, along with their linnet nests full of young.

A whole chapter is given to the domination of Hilly Piece by its crop of thistles. HW is determined to win the battle and grow wheat there. Triumphantly he succeeds.

The exposure of the clods to sun and air charged the land with goodness. The seed-bed for wheat was ready.

He next tackles the complications of ‘Arbitration’; but first the problem of ejecting ‘Napoleon’ from the double cottage which was supposed to be the farmhouse. Dreading the court ordeal, it is all over in minutes: the solicitor says he can offer no defence. (HW’s diary records this as Friday, 29 April 1938: ‘Francis went out of the cottage today’.) A week later, according toThe Story of a Norfolk Farm (the actual date was 27 May 1938), he attends the Court of Arbitration at the Kings Arms Hotel at Great Wordingham (Diary: ‘Crown Hotel, Fakenham’). Present: the Arbitrator, Mr Gotobed (Harris), Strawless (Stratton), Stubberfield (Dewing) and his clerk, and Barkway (Hawkins) with clerk and solicitor.

The ensuing proceedings were of course a farce and a travesty of justice. The account runs to eight pages of amusing description. In real life it was a nightmare, HW being taken for a ride by a clique of crafty local Denchmen. HW’s diary includes:

They made ridiculous defence of non-doing of repairs. . . . He [Stratton] is just a rotten liar.

There is a further four-page chapter detailing the bills HW subsequently received. He is now heavily in debt.

There was only one thing for it: to pay off the debts by writing. In the succeeding six months and working most days on the farm, I wrote and delivered, after the day’s work, eighteen broadcasts and twenty-two articles, in addition to The Children of Shallowford, and thereby managed to pay the money owing to Mr. Stubberfield, Mr. Barkway, and Mr. Sadd. In spring the snipe, uttering their queer throbbing cries, still flew happily over the undrained meadows. I could not bear to hear them.

Although there is no mention of it here, his deep depression was mainly caused by the fact that Ann had written from Chippenham (her mother’s home) to say she was not coming back. He was shocked to find his wife telling him very plainly that it was his own fault. He was now in a state of considerable emotional turmoil.

Part Four: REALIZATION

HW’s depression, his feeling of alienation, is epitomised in his attitude over the filthy state of the little Stiffkey River and the uncaring local attitude, leading on to the Night Cart (the system of collecting human effluent), and which leads him to relate the tale of the late rector, ‘Little Jim’, who had been unfrocked for his behaviour (he befriended London prostitutes in the hope of ‘saving’ them) and lack of attention to parish duties, and had then joined a circus, meeting an untimely death when his nightly act of putting his head in a lion’s mouth ended on the night said lion closed its mouth with a snap. This bizarre tale is entirely true. The body of Harold Davidson, one-time vicar of Stiffkey, was brought back and buried in Stiffkey churchyard. HW had witnessed the funeral when he first arrived at the farm, taking photographs of the hearse arriving and the coffin being carried into the church.

|

|

Harold Davidson's grave today, in the foreground (photo © 2008 John Gregory) |

The point of HW’s tale here is that the contents of the Night Cart, and all village rubbish, were deposited on the field opposite his own Fourteen Acres, where its stinking contents attracted rats and flies – incensing our author.

Harvest time finds him more optimistic. In the book HW states they started to cut the oats on 10 August 1938, although his diary records this as 29 July. His photograph of the men standing the stooks up is indeed dated 9 August! No matter: the account itself is an expanded version of terse diary notes.

The next chapter deals with the pigs. HW’s diary shows that the pigs have been a source of friction from the time he first bought them. The men resist every idea their boss mentions and stubbornly stick to their old (inefficient, backward) methods. Eventually HW loses his temper and lets the pigs out to roam free and prosper. Interestingly he inserts here, in parenthesis, the response of the men to his outburst: ‘(“We reckon it was the war that done suthin’ to our boss.”)’

He paints a word picture of a happy contented family scene having tea on the grass by the barn, with amusement caused when both Baby Richard (now 3 years old) and five year-old Robert have their food removed from their fingers by a quick-beaked hen. For a brief period, all is well.

Although the harvest is over there is no time to enjoy the nature all around, although we are treated to one of HW’s lovely lyrical passages which leads into a description of a kestrel – a ‘windhover’ – and a rare sight in Norfolk, where gamekeepers assiduously protect their pheasant poults for shooting. HW remembers the tame kestrels of his youth that he had to leave behind when, ‘wearing a new khaki uniform’, he left for the war in August 1914.

Wing-shivering, filaments of nestling-down waving on new feathers . . .They followed me over the hill to the station, and I never saw them again.

And one feels he has mentally added the lines he wrote at the end of his childhood ‘Nature Diary’:

And Finish, Finish, Finish

the hope and illusion of youth

for ever and for ever and for ever.

Note also the echo of Gerard Manley Hopkins poem ‘The Windhover’ in his own words above. An anxious Windles asks him not to shoot them.

Ride the autumn wind, little falcons: we shall not harm you.

The battle with rats, and the bogus rat-catcher is the next episode related: again it is amusing to read – but rats were a very real and serious problem.

Accounts have to be kept and an annual balance sheet made out. HW sets to work with great trepidation of what he will find. At the end he is appalled to find he is nearly eight hundred pounds out of pocket (the figures are given in full). But this is balanced by the fact that the farm itself is much improved and many of the losses are inevitable. He can even, with a bit of juggling of the facts, tell himself that the loss was actually only 9s 10d (a fraction under 50p in ‘new money’!).

Much of the problem is due to Government policy: cheap imported crops and imported Argentinian beef. He busily writes an article to earn money to help remedy his own monetary plight, but also to inform the public of what the situation really is. (The article, headlined ‘There’s a lot of angry talk up here . . .’, was printed in the Daily Express on 14 December 1938; and collected in Chronicles of a Norfolk Farmer, HWS, 2004; e-book 2013.) He also mentions in his diary a further series of broadcasts: 22 August 1938: ‘Broadcast 7 p.m. tonight, first of four farm-venture series “Close to Earth”.’ But he notes in the book that he is asked to tone down his comments on the state of agriculture for Overseas Listeners: ‘they wanted to hear that everything was fine in the Old Country’.

Chapter Forty-four relates the famous ‘Farmhouse Party’; but first HW gives the details surrounding getting access to the cottage chosen as his farmhouse, Walnut Tree Cottage, which had been occupied by the recalcitrant Napoleon and his somewhat eccentric ‘Lady Norwich’ wife. (As noted previously, this was actually on 29 April 1938.) HW and Loetitia explore the house, planning the improvements they will make. They both start to itch and are covered with ‘small brown insects’ (fleas): HW’s sense of humour could not resist – ‘Napoleon’s army was victorious!’ Soapy water and paraffin sprayed on them was useless. HW poured neat paraffin on his bare legs covered with swarming insects, but the only effect was to make himself feel sick. Even burning sulphur did not kill them, until a second visit when he laboriously sealed up every hole and crack and lit sulphur in every room.

In the morning thousands of corpses, bleached to a shrivelled yellow, lay on the floor.

Napoleon’s army was finally vanquished.

HW now needed to solve the problem of access by the next-door cottage through his own property. When he went to discuss this with the owner of the cottage – Mr Louis Cafferata, new owner of the Hall, he offered to sell it. This was ‘River View Cottage’ (14 Church Street). HW’s diary 16 May 1938 records:

Today I bought, unexpectedly, a cottage from L. W. Cafferata of Old Hall one adjoining Walnut cottage (ex-Francis) for £82/10/- : a bargain!

Renovations to Walnut Tree Cottage proceeded apace and they decide to have a party to celebrate. As the cottage wasn’t actually ready this would be held in the granary (a much more suitable place anyway). The event is recorded in his diary as taking place on Saturday, 19 November 1938.

The passage describing the farm party is a gem. Present are the family, Loetitia’s cousin Mary (one of her bridesmaids), John (John Heygate), a Fleet Street friend (John Rayner, who as Features Editor of the Daily Express was responsible for publishing HW’s many articles during this period), a famous painter of horses (Sir Alfred Munnings), and the guest of honour (the film star Robert Donat, currently filming the film Goodbye, Mr Chips, for which he won an Oscar for Best Actor.)

So let us eat, drink, and be merry. Here is the granary, lit by fifty candles, and the [eleven-foot] refectory table [brought up from Shallowford] . . . laden with all sorts of good things. . .

Several candles were stuck on the table, which bore a cold turkey, a ham, roast pheasants, potatoes in their jackets, a salad, with our own butter . . . home-baked bread of the full wheaten berry ground in our own mill in the chaff-house. . . .

And to wash it all down more of HW’s Algerian wine. They wear a selection of unsuitable hats and are very merry. Sadly Robert Donat has to leave early as he was filming the next day.

The feral cat Tommy-tommy, tame while HW had lived in the granary the previous year but now turned wild again, watches from a distance.

When the last bottle had been drained, the last guttering candle snuffed, when the Ballad of the Cafe Royal, with encores . . . had been declaimed by the artist (Munnings was renowned for singing bawdy songs with very little encouragement!) . . . when the granary was silent . . .

then Tommy-tommy and the other cats, and the rats and the mice, came and feasted on the remains.

The next day, Sunday, 20 November 1938, HW’s diary notes:

In evening we all went to Fakenham & heard Mosley . . . I thought I’d make this the climax of the Norfolk Farm book.

Two important points there: firstly, this is the first mention in the diary of this book – and secondly, the printed book contains no reference to this meeting. (This is the deleted material, but to avoid interrupting the flow here, please see Appendix A for explanation.)

The next chapter deals with ‘The Barley Market Crash’, opening:

My Editor printed some articles about the collapse of the barley market in 1938 . . . adding a Photostat of the envelope in which it was sent, with my note: ‘There’s a hell of a lot of angry talk up here among farmers. . . .

(This article, dated 14 December 1938, with the copy of HW’s envelope note as an illustration is reproduced in Chronicles of a Norfolk Farmer.)

The Barley Market crash was a huge blow to the farming fraternity and certainly to HW. It was one of the best harvests ever and resulted in one of the lowest prices gained ever: due, of course, to cheap imported grain.

HW describes a protest meeting by farmers, one of a series, in Norwich, which he attended. He tells us of the long, drawn-out, boring, almost meaningless speeches made; and eventually, past ten o’clock, when it was his turn to speak, how he abandoned what he had so carefully prepared and instead merely shouted out that the only answer was to march on London and confront the City, and force it to listen to save Britain:

. . . from the biggest slump in history, or alternatively from another European war.

This occasion is perhaps what HW meant when he noted he had spoken at meetings.

The idea of a march does get taken up, but gets taken over by the Farmers’ Union – a conflict of interest, as the chairman of this is also the new Minister of Agriculture! It becomes a meaningless event attended by the ‘wrong’ farmers. However:

The Prime Minister made a speech at Kettering, which told the truth: that if farming became prosperous, if the land were made fertile and in good heart, the overseas business interests of Britain would suffer. It was an honest speech.

The next chapter would have been the one that was removed (see Appendix A). Instead we go straight into ‘Norfolk Tarkies’. The original four poults and one male ‘stag’ turkey had produced a large number of eggs, but although half of them never hatched, those that did thrived as free range birds, roosting in the high trees of Fox Covert. Inevitably at Christmas time they are sold.

At night, wandering round the woods, I missed dark shapes against the moon which had been our ‘tarkies’ roosting in the tree-tops.

The scene changes to wildfowling: a useful source of food for a man with a growing family. He describes a ‘fall’ of woodcock (a large number of birds flying across from Scandinavia, which land exhausted into the sandhills on the coast). He shoots a pair of pigeons and then another pair, and then to his surprise brings down a duck (see his article ‘Bang! My First Wild Duck!’, Daily Express, 3 January 1939, collected in Chronicles of a Norfolk Farmer).

He then relates a story about a yellow owl – a woodcock owl –

Strangely light: all feathers, smoke-yellow and dead-reed mottled, softer than velvet . . .

These are short-eared owls, which also migrate across from Scandinavia, and the story tells that tiny fire-crested wrens (our smallest bird) cling onto their feathers to hitch a ride across the North Sea.

1939 is rather hastily skated over in the next twenty pages: the annual round of farm work is repetitive and would cease to be interesting for readers. But we now have a tremendous description of wind, rain and subsequent flood, and how it affected every part of the farm and its occupants – even tearing the hood off the Alvis. But HW is not dismayed. He finds that many of the measures he has taken to improve the farm – in particular his drainage system – are working, and his stock – pigs, cows etcetera – originally in dire straits, are all safe and looking good. The tale of the lone turkey who built her nest on flooded ground which they rescue by rebuilding the nest, has a ring of ‘parable’ about it.

After the flood, frost and snow: a further superb description relates walking back with difficulty from a Christmas shopping trip with Windles to the nearby coastal town four miles away (Whelk, or Wells-next-the-Sea) in a raging snow-storm. By the time they get back the snow has stopped: all is quiet and still and white.

I wanted to take the silence, and the rare peacefulness, to myself, and leaned against a flint wall to think back into the past, and hark! Up there in the sky . . . marvellous sound! Star talk of the wild geese flying inland to their feeding-fields.

How his writing skill has transformed the prosaic diary entry for 22 December 1938:

Snow everywhere. Walked from Wells with Windles, along the coast, & got in a blizzard.