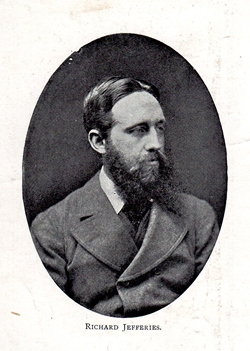

RICHARD JEFFERIES

HW’s ‘Introductions to’ and ‘Selections of’ the writings of Richard Jefferies (1848–1887)

|

|

| Richard Jefferies | |

Henry Williamson and Richard Jefferies

Richard Jefferies Centenary Celebrations, June 1948

Henry Williamson and the Richard Jefferies Society

The Amateur Poacher (Cape, 1934, The Travellers’ Library, No. 202)

Wild Life in a Southern County (Cape, 1934, The Travellers’ Library, No. 203)

The Gamekeeper at Home (Cape, 1935, The Travellers’ Library, No. 205)

The above all have the same 5-page Introduction by Henry Williamson

Richard Jefferies: Selections of his Work, with details of his Life and Circumstance, his Death and Immortality, by Henry Williamson (Faber, July 1937; revised reprint 1947)

Hodge and his Masters, revised by Henry Williamson, with a Foreword (Methuen, 1937)

A Classic of English Farming: Hodge and His Masters (Faber 1946, reprinted 1948)

Bevis: the Story of a Boy, Introduction by Henry Williamson (Dent, 1966, Everyman’s Library, No. 850)

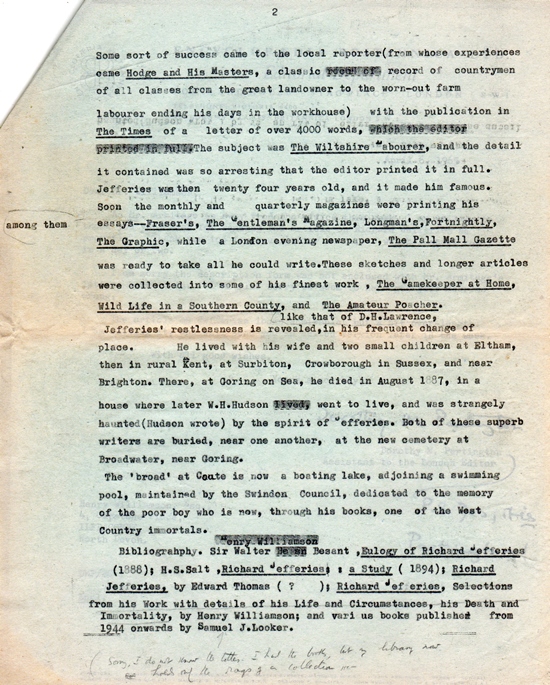

Richard Jefferies was born at Coate Farm, near Swindon, Wiltshire, with a farming and country background. He was always a loner roaming the countryside, but he did not want to follow his father and become a farmer. Instead in 1864 he became a journalist on the North Wiltshire Herald and, after his marriage in 1874, began to write books to supplement his income. This is not the place for biographical details of his life: readers wanting to know more should consult appropriate sources.

Jefferies’ love of all country matters was innate, but his life was always a struggle. He first came to the notice of the general public with a long letter in The Times on the plight of the agricultural worker.

His many books include a handful of slightly ‘gothic’ style novels of which the best known is Amaryllis at the Fair (1887). But his main body of work covers rural scenes and subjects: The Amateur Poacher (1879); The Gamekeeper at Home (1880); Hodge and his Masters (1880); Greene Ferne Farm (1880); The Open Air (1885); After London (1885), a somewhat apocalyptic vision of future disaster caused by industrial life and a plea for a return to a more natural life, the only true way to exist; and Field and Hedgerows (1889 published posthumously).

He remains best remembered perhaps for two particular works: Bevis, the story of a Boy (1882), a fictionalised and idealised version of his own young life; and the extraordinarily mystical outpouring of thought in The Story of my Heart (1883).

Jefferies struggled with debilitating tuberculosis for many years, finally succumbing in 1887, aged 38. He is buried in Broadwater Cemetery near Worthing in Sussex, very near that other great naturalist and writer, W. H. Hudson.

*************************

Books on Jefferies often feature a frontispiece with variations of this well-known portrait, either as a photograph, drawing or etching:

|

|

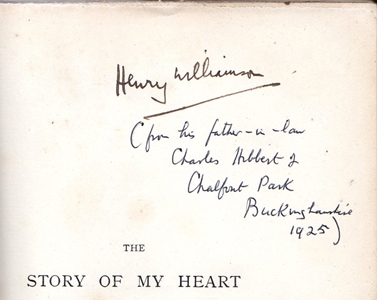

The title page of Charles Hibbert's ('Pa' – HW's father-in-law) copy of the first edition of The Story of my Heart:

Pa gave the book to HW, who annotated the half title thus (though Pa had not lived at Chalfont Park for very many years):

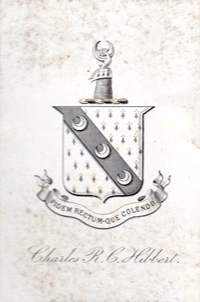

Pa's book plate, showing the family motto and crest:

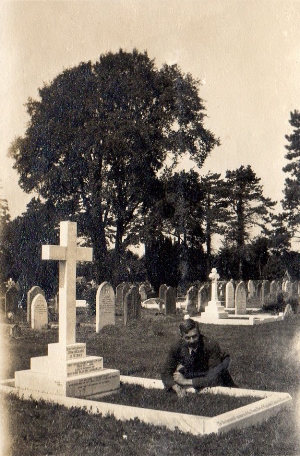

HW at Jefferies' grave, when he visited with Gipsy in August 1936:

|

|

Henry Williamson and Richard Jefferies:

HW’s connection, appreciation of and affiliation to the work and spirit of Richard Jefferies began at a very early age and continued throughout his life; Jefferies’ influence is diffused and evident in much of his work. Practical evidence of this can be found in HW’s editing of some of his mentor’s work, and this is gathered here under one umbrella – although most will therefore be out of sequence in the overall chronological time-scale of HW’s ‘Life’s Work’ – in order to give emphasis to this very important area.

Jefferies’ influence on HW has been well documented. For example, see particularly: Dr Wheatley Blench, ‘The Influence of Richard Jefferies upon Henry Williamson’, Part I, HWSJ 25, March 1992, pp. 5-20; Part II, HWSJ 26, September 1992, pp. 5-31 (Part II is scanned in two sections; Section One and Section Two). There are many other references within the HWSJ, particularly the special issue, HWSJ 41, September 2005, which contains several major items concerning HW and Jefferies, and indeed W. H. Hudson).

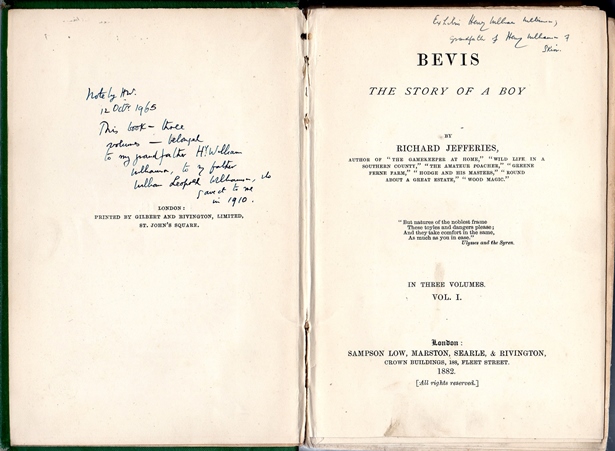

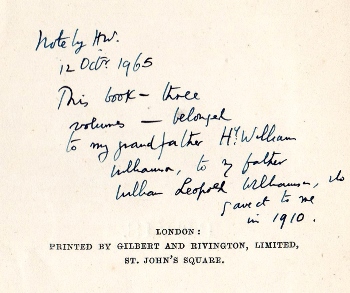

It had all started at a very young age. HW’s grandfather (Henry William Williamson senior, 1834–1894) had had a copy of the first edition of Bevis, published in three volumes. He had given this to his eldest son, William Leopold (1865–1946, HW’s father) who in his turn had given it to his son, HW, when he was about ten years old. HW frequently referred to the joy the book gave him as a young lad. The books still exist, but are now very fragile. The first volume is inscribed:

The inscriptions enlarged:

HW had also read at least some other books by Jefferies, and when he left school in the summer of 1913 was disappointed that the Jefferies books he had asked for as his prestigious Bramley Prize (for an essay) were instead two huge volumes of The Bible in Art. He wrote in his schoolboy 1913 diary that he intended to get Jefferies books with any money left over (but I don’t think that occurred!).

In early 1919, still in the army and stationed in Folkestone, it was his discovery of a copy of Jefferies’ The Story of My Heart in a second-hand bookshop, at a time when he was much traumatised in the aftermath of the war, which was a turning point in his life. He found himself in complete empathy with all Jefferies’ thoughts, giving him the determination to follow in Jefferies’ footsteps and reinforcing his intention to become a writer himself.

This volume was not in his archive and was thought to be totally lost; but recently somebody made contact as owner of the book, and very kindly loaned it so it could be verified. Carefully trying to work out its provenance via tiny details in the archive, it would seem that HW sent this book to his ex-headmaster at Colfe’s Grammar School, Mr. E. V. Lucas, and that at some point afterwards it was sold on. HW had illustrated the flyleaf of his copy in this fashion – doodling, perhaps, while his mind should have been on service matters!

HW left the army in September 1919 and began work seriously on his first novel. In 1920 he began keeping a ‘Journal’ in a large (folio-sized) second-hand alphabetised ledger into which he poured all his thoughts, ideas and plans for stories etc. He dedicated this Journal to Richard Jefferies, and decorated the cover with further drawings of his barn owl totem:

Evidence of the influence of Richard Jefferies abounds in his early writing, where the mystical Romantic elements are evident, together with the interest in nature and the influence of our ancestral and mystical past.

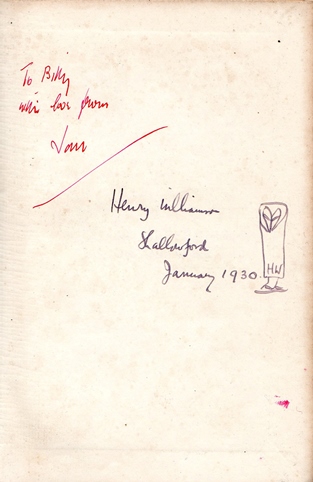

In 1930 HW was given (by his friend and fellow-writer Jan Mills-Whitham) a copy of Edward Thomas’s biography Richard Jefferies: His Life and Work (Hutchinson, 1908), which Thomas dedicated to W. H. Hudson.

Jan Mills-Whitham's inscription:

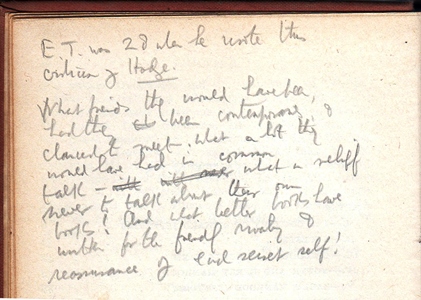

On the next page HW noted in pencil:

Thomas's biography is a useful, well-written and sensitive work, taking the reader through Jefferies’ life and writing. The final chapter, ‘Recapitulation’, particularly grasps the essence of his subject. It also contains a handy chronological bibliography.

HW also had copies of Walter Besant’s Eulogy of Richard Jefferies, written immediately after Jefferies’ death in 1888; Henry Salt’s Richard Jefferies: His Life and His Ideals (1894); and various other works. By this time he also had a very good collection of Jefferies titles, as illustrated below. Many of them came from the library of his father-in-law, Charles Hibbert, who had a complete collection of first editions of Jefferies titles (along with many other excellent natural history works).

*************************

There is no clear archival evidence to reveal what actually led HW to edit Jefferies’ writings, other than that he would have had a natural urge to bring his great mentor to the fore. His 1929 diary notes re ‘work in hand during March’ to include:

3. Preface to Gamekeeper at Home

4. Read Jefferies & prepare Introduction to his selected essays.

For some reason this work was delayed until 1934, when a very friendly (and clear) letter from Jonathan Cape dated 30 May shows that the idea had been discussed:

As to the Jefferies introduction; the fee is ten guineas and I want it to be not less than twelve hundred words, but you can of course make it as long as you like. I would like the introduction to be one which deals with WILD LIFE IN A SOUTHERN COUNTY, THE GAMEKEEPER AT HOME and THE AMATEUR POACHER. It could then be applicable to all three books. If you prefer, or find it easier, to write three introductions, one for each book, that would suit my purpose equally well – in fact rather better. There would have to be approximately a thousand words for each in length and I could offer you twelve guineas for the three.

(Note how carefully Cape is setting out these terms: he intends no repetition of earlier problems he has had with HW!)

HW baulked at writing three separate Introductions, and we find the same Introduction by him, dated June 1934, appearing in three separate Jefferies’ titles published by Cape:

|

|

| Jonathan Cape, 1935 |

The Amateur Poacher

Cape, 1934, The Travellers’ Library, No. 202

Wild Life in a Southern County

Cape, 1934, The Travellers’ Library, No. 203

The Gamekeeper at Home

Cape, 1935, The Travellers’ Library, No. 205

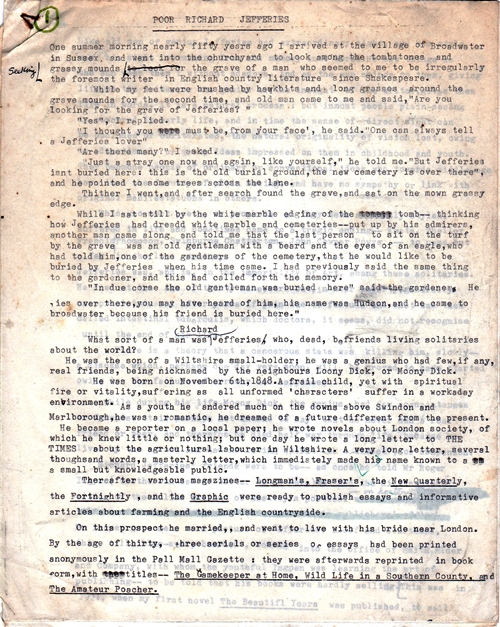

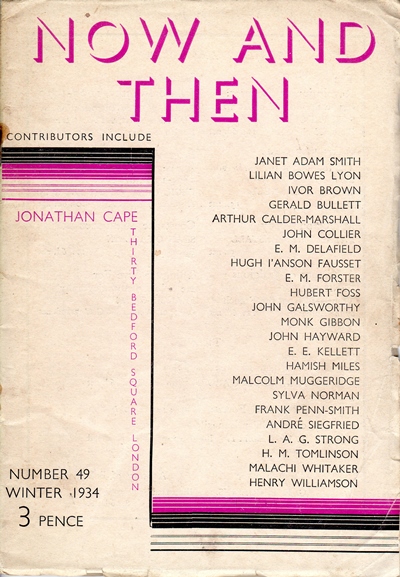

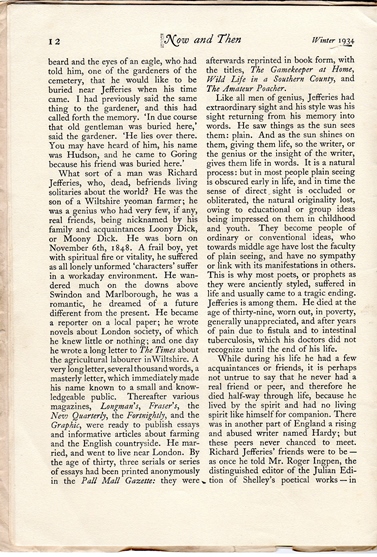

This Introduction was reprinted first in Cape’s house magazine Now and Then, No. 49, Winter 1934 (in the same issue as their rather low-key advertisement for The Linhay on the Downs) and, later, in their anthology Then and Now (Cape, 1935).

The first page of HW's TS Introduction:

|

|

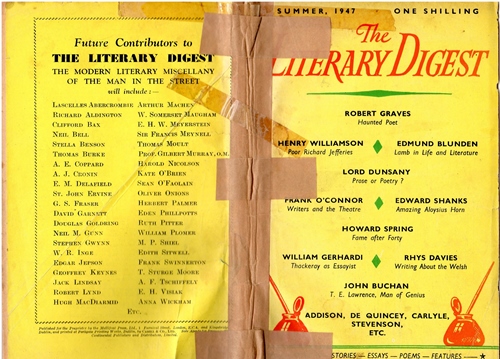

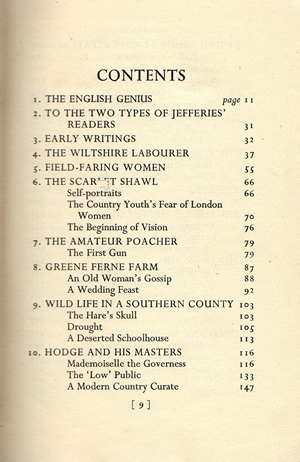

It was also reprinted in an abridged version in The Literary Digest, summer 1947.

*************************

In 1937 HW made a far more major foray with:

|

|

|

First edition, Faber & Faber, 1937 |

Richard Jefferies: Selections of his Work, with details of his Life and Circumstance, his Death and Immortality

Faber, July 1937; revised reprint 1947

For this HW wrote a substantial ‘Introduction’ in two parts: I, ‘The English Genius’ (pp. 11-30); and II, ‘To the Two types of Jefferies’ Readers’ (p. 31). (Part I of this ‘Introduction’ is reprinted in Indian Summer Notebook, ed. John Gregory, HWS, 2001; e-book 2013.)

There is also an ‘Epigraph’, where HW explains his own route through Jefferies’ work. At this time HW was at a crossroads. Life as he knew it was in a great state of flux. It is obvious here that he was transferring his own feelings on to those of Jefferies (as he also did with T. E. Lawrence at this time). Jefferies had found great difficulty to begin his great work – HW found it impossible to begin his: both men are concerned with facets of ‘Ancient Sunlight’. Jefferies had fought his ‘three giants of disease, despair, and poverty’: HW was fighting his own giants – giants arising from his own traumatic past of the First World War and now the future looming of another World War. He had visited Germany, seen what was going on, and now was in the process of leaving Devon for the farm he had bought in Norfolk. There is no doubt that he was in a great state of turmoil and confused thought.

There are brief notes at the beginning of each section, each containing two or three selections covering most of Jefferies’ books: thus bringing a large area of Jefferies’ total opus to the notice of readers in one volume. Here is what he wrote about Bevis:

His choice of selections offers a comprehensive coverage of Jefferies' books:

|

|

The book also had a scattering of photographs, three of Jefferies, with one of his memorial bust, and also four photographs taken by HW himself (or his wife). HW had his own copies of various photos of Jefferies.

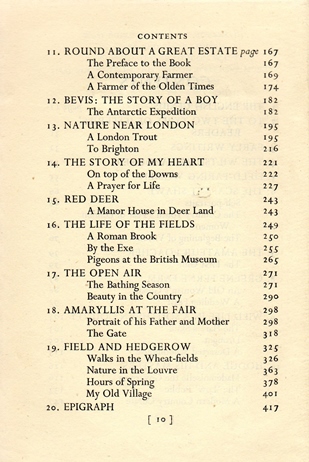

The photograph above, in the Bevis extract, shows HW wandering at Coate Water, and is captioned: ‘Bevis’ New Sea, where the Nile flows into Fir-Tree Gulf, January 1937’.

HW states that he made a visit to Coate Water in 1925, the year he got married. There is no actual evidence of this visit, but as his bride was also a lover of Bevis then they quite possibly did make a visit during that year. But certainly in 1936 he and his wife Gipsy, and their eldest son Windles, called in on 27 August after a visit to the Norfolk Farm, and HW recorded in his diary, ‘bathed in Jefferies’ lake at Coate’.

In January 1937 HW made a further visit, again calling there with his wife on his way back to Devon (this time after a difficult session with Ann Thomas at Tenterden, who had told him she was about to marry someone else). He recorded that he took photographs for his book of selections from Jefferies’ writing. However the photograph ‘Coate Water Today’ must have been taken on the August 1936 visit, as HW states there were ‘Thousands of people were swimming, boating, walking about’:

Hardly thousands! – HW was seeing it with regret for Jefferies’ idealised portrait in Bevis, where the two adventurous boys had this momentous ‘sea’ to themselves.

The other photographs in HW’s Selections are ‘Coate Farm (thatched in Jefferies’ time) today’:

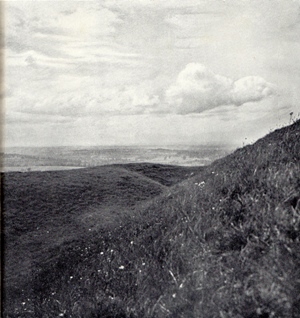

‘Roman earthwork above Liddington’:

It was climbing that earthwork – Liddington clump – that inspired Jefferies’ writing in The Story of my Heart:

I was utterly alone with the sun and the earth. Lying down on the grass, I spoke in my soul to the earth, the sun, the air, and the distant sea, far beyond sight.

In his short introductory paragraph to his selection from this important work, HW wrote:

It is, for me, one of the most beautiful and most noble books in the world.

HW’s selection includes the passage that contains the words he wrote at the front of his 1920s ‘Richard Jefferies Journal’:

It is eternity now, I am in the midst of it. It is about me in the sunshine; I am in it, as the butterfly floats in the light-laden-air.

HW’s equivalent of Liddington Clump was Caesar’s Camp – the ancient hill fort overlooking Folkestone, where in 1919 he first read The Story of my Heart, and where on ‘Peace Night’ 1919 he had his own mystical experience. Jefferies’ book affirmed his own life’s purpose.

He notes that there was a time when The Story of my Heart was considered ‘dangerous’ for a young impressionable youth. It hardly seems possible that such visionary thought could be so labelled.

HW’s book Richard Jefferies: Selections went into several editions over the years. The 1947 new edition, also published by Faber, has an additional extract: ‘A Pageant of Summer’ from Life in the Fields.

*************************

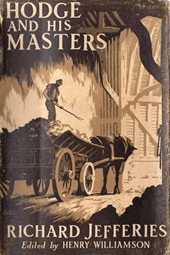

Also in 1937 HW produced a new edition of:

|

|

| First edition, Methuen, 1937 |

Hodge and his Masters, edited by HW, with a Foreword

Methuen, 1937

Here HW edited Jefferies’ text to a high degree: changing the order of chapters, leaving some out, ‘cut and pasting’ others (that is, moving passages of actual text around within chapters) and changing the headings. He felt this would make the book more acceptable to ‘modern’ readers, but it is known that Jefferies’ closest adherents resented (understandably) this interference with the master’s work. The book has a nice selection of 10 photographs which had all previously appeared in The Farmer’s Weekly.

HW’s Foreword opens: ‘This is a rich and beautiful book of England.’ He states that Jefferies was too overworked and too ill to do the book justice: that if Jefferies had had time and energy to correct it, he would have done what HW has now done – and he goes on to tell readers what that is. (As HW himself became a farmer from 1937 to 1945, his editing of this volume was particularly apposite.)

The frontispiece features an evocative portrait of 'Hodge':

In 1946 HW produced another edition of Hodge and his Masters (sadly without the photographs), giving it the new title of A Classic of English Farming: Hodge and His Masters (Faber 1946, reprinted 1948). Inside his copy of the first edition of the book, he wrote:

For this new edition, the introduction for the original Methuen edition was first amended:

and then re-written:

Note, though, that the actual new printed introduction has considerable further alterations!

*************************

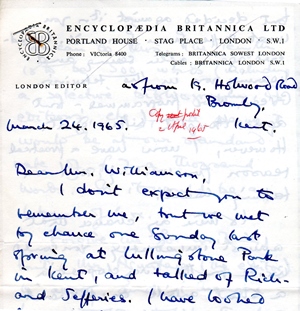

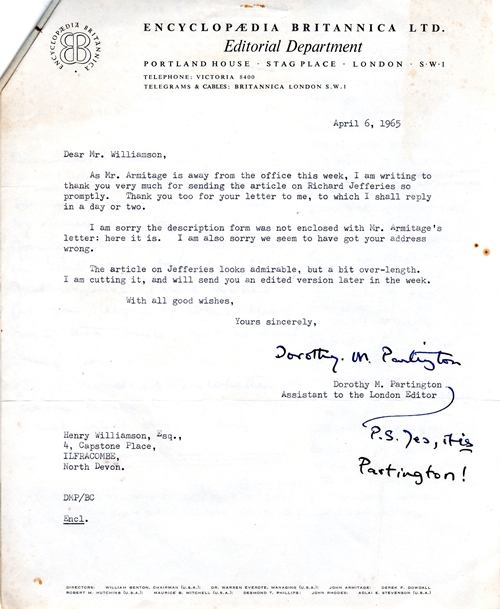

In 1965 HW was asked by Encyclopædia Britannica to write (at short notice) an article on Richard Jefferies, as they had an unexpected chance to replace ‘our present inadequate article’. HW composed a short tribute forthwith.

*************************

Then in 1966 HW wrote an Introduction for a new edition of:

|

|

| Dent, 1966 |

Bevis: The Story of a Boy

Dent, 1966, Everyman’s Library, No. 850

(First published in 3 vols, 1882)

HW's Introduction opens: ‘“Moony Dick”Jefferies as some called him in boyhood . . .’, referring to Jefferies habit of ‘mooning’ or ‘roaming’ around the countryside, on his own and avoiding contact with others. Bevis is one of those classic stories of boyhood – as HW notes: ‘Bevis and his friend Mark are the heroes; and what adventures they have!’

Those adventures include a mock battle between Caesar (Bevis) and Pompey (a boy called Ted) which they call ‘The Battle of Pharsalia’ – which develops into a real fight; Bevis runs off and eventually gets himself on to a secret island where after some time he is found by Mark. (One is reminded of HW’s scene in The Beautiful Years, when Willie runs away after the death of Jim Holloman: further evidence of Jefferies’ influence on HW’s early writing.)

The scene of the book is based on Coate Water, and is an idealised version of Jefferies boyhood. It is a vivid story of how a child’s imagination takes him into his own world. HW writes here, 'Clear sight is the base of all good writing . . . the true artist sees clearly and with wonder. . . . It is this quality that makes Bevis a book almost unique in its class.'

We are given a map of Bevis’ ‘New Sea’ as a frontispiece:

*************************

In 2005 the Henry Williamson Society marked its ‘Silver Jubilee’ with a ‘Special Issue’ of the HWSJ (no. 41, September 2005), almost entirely devoted to the two men who so greatly influenced HW: Richard Jefferies and W. H. Hudson. Apart from reproducing a great number of items from HW’s archive, this issue includes an excellent article from a talk given by a member of the Richard Jefferies Society, the poet Richard Stewart: ‘Henry Williamson’s Debt to Richard Jefferies’.

*************************

In 1936, HW produced an anthology, not just of Jefferies (or even Hudson) but a whole array of extracts from writers on the natural world. It seems appropriate to include that here.

|

|

| First edition, Nelson, 1936 |

An Anthology of Modern Nature Writing

Nelson, Modern Anthologies, No. 6, May 1936

HW’s Introduction gives brief but interesting notes on each of his chosen authors, and his list makes an interesting appraisal of natural history writing (as did his ‘Reality in War Literature’ essay on the First World War):

The anthology was reissued in 1948 in Nelson's new ‘Argosy Books' series’, of which this was the second. The series was intended for 'those who value quiet ample writing refreshing to minds weary of the alarums of our time. Their main purpose being to answer the need for intelligent pleasure, books have been specially chosen that have a marked unity of mood and style.'

The eclectic nature of his selection is shown by the Contents pages:

|

|

Pasted on the inside cover of HW's copy of his anthology is this cutting about his forthcoming broadcast 'Red Deer'. The reaction of readers of Cruel Sports to the talk is not known. The text of the broadcast features in Goodbye West Country – interestingly, in different working versions in parallel text; and is collected in Spring Days in Devon, and other Broadcasts (edited by John Gregory, HWS 1992; e-book 2013):

(There are other HW anthologies over the years: total coverage of every item is impossible.)

*************************

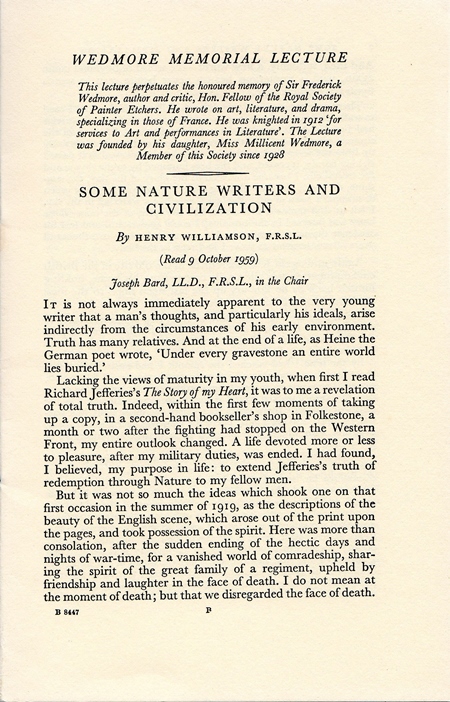

In 1958 HW was made a Fellow of the Royal Society of Literature (FRSL). (For background, see Anne Williamson, Henry Williamson: Tarka and the Last Romantic (1995), and Fred Shepherd, ‘A Visit to the Royal Society of Literature’, HWSJ 32, September 1996, pp. 35-6.)

The following year he was invited by the RSL to give the prestigious Wedmore Memorial Lecture on 9 October 1959. His title was 'Some Nature Writers and Civilisation', his chosen authors being chiefly Richard Jefferies and W. H. Hudson, the two writers to whom he felt most indebted. This is an important item within HW’s total oeuvre. The essay was printed in Essays from Divers Hands, Vol. XXX (the annual Transactions of the RSL) (OUP, 1960), and reprinted by OUP as a single pamphlet item at the author’s request (it is thought there were about 100 copies). (The essay is included in Threnos for T.E. Lawrence & other writings, ed. John Gregory, HWS, 1994; e-book 2014.)

(See 'Some Nature Writers and Civilisation' for further details about this lecture.)

*************************

There are a considerable number of cuttings concerning Jefferies in the archive files, but many of those are to do with Jefferies’ life and philosophy and do not really concern the immediate subject here. They reflect the intense interest in Jefferies held by HW throughout his life.

Hodge and His Masters, 1937

There are a handful of reviews which interestingly compare HW’s edition with Samuel J. Looker, Jefferies’ England (Methuen 7/6d), and so highlight the rivalry between them.

The Friend (William Graveson), 3 December 1937:

Looker’s book contains a selection of about thirty essays grouped according to the seasons . . . a sympathetic introduction and a useful bibliography, illustrated by Will Taylor.

Hodge . . . first published 1880, revised by the well-known West Country author, Henry Williamson, . . . The keynote to the book may be found in Williamson’s exclamation, “Bravo, Jefferies, you’ve given us a whole countryside last mid-century.” . . .

The value of the book is in its portraits of farmer and labourer, squire and parson, mademoiselle the governess; and of the trials and pleasures of the countryside folk.

Cornhill Magazine, December 1937; Contrasts Looker’s book to HW, rather favouring Looker as the better volume. On HW:

One may question the propriety of [HW’s] revision . . . but at least the revision is done with loving knowledge in the hope that new readers will be found for this very interesting account of more than fifty years ago.

New Statesman & Nation (Robert Waller), 4 December 1937; A ten-inch column which is purely a review of Looker’s book but refers to HW’s Selections:

It is fifty years since Jefferies died. Two books have commemorated his jubilee. The first was Henry Williamson’s selection reviewed in these pages a few weeks ago. [Not in file!]

[This reviewer makes it clear that he prefers the Looker volume. Looker] describes the nature of this change [between early & late RJ] without the fantastic comparisons and claims which spoilt Mr. Williamson’s work.

Manchester Guardian (A.W. Boyd), 3 December 1937; A long column reviewing ten books of varying natural history subjects headed as ‘The English Scene’ (Jefferies heads the list). It again compares the Looker and HW volumes, but merely notes both have been published, and then continues with thoughts on RJ himself.

Oxford Times, 21 January 1938 (22” column):

‘Dr. Jekyll’s Notebook’ by Jekyll Junior

Farming Sixty Years Ago

[A review of Hodge: a thoughtful and detailed article, highlighting and analysing the problems of farming, continuing:]

But now a new edition of “Hodge” revised and edited by a great admirer of all that Jefferies wrote, has just appeared. Mr. Henry Williamson has taken the old work as though he had taken a series of separate articles, and dealt with them as he feels Jefferies himself might have done. . . .

Mr. Williamson’s revision deserves only praise, for he has carried it out with such sympathy with Jefferies’ outlook and such understanding of his method of writing . . . that [indeed] the author might have done the work himself. . . . It is a story of the English countryside then and now, and for ever.

British Weekly, 19 December 1940 (12” column); subheading, presumably as publisher: ‘St. Hugh’s School, Bickley, Kent’: print is as a newspaper. The general tone of the reviewer of five books here under heading title ‘Land and People’ is that books on country life will strengthen the reader in these dark days and difficult times. HW gets:

It is good to note the addition to the Faber library of [Richard Jefferies: Selections of his Work] . . . This book was a marriage of true minds, and now is a good time to issue it in a cheap edition.

************************

The 1947 reprint of Richard Jefferies: Selections of his Work quite interestingly got quite a wide coverage, although some of these were very brief. Here is a selection of those that had more interesting comment.

Daily Herald (John Betjeman), 20 May 1947 (‘Betjeman on Books’); A slick column in typical ‘Betjeman’ vein – in total a 30” column:

If it were not that there are so many books worth mentioning . . . I would spend all this column in praise of Richard Jefferies. . . .

Henry Williamson’s selection and notes on him have been reprinted . . . on chemical green paper. [War economy restrictions] Despite a hectoring preface, “if you don’t like Jefferies, you are no good”, this is a learned, sensitive, enthralling selection. It shows the two sides of Jefferies – the portrayer of natural downland scenery and wildlife, the speculation on eternity and man’s purpose in creation. . . . This is a book I shall hold on to after I am sold up.

Oxford Mail (S. P. B. Mais), 15 May 1947:

There are few writers for whom I have a deeper respect than Jefferies and Williamson. . . . The astonishing thing about this book [Selections] is its modernity. . . . It tackles all the problems that still perplex the family and tackles then with very unusual good sense.

Mais goes on to remind readers of HW’s Hodge and his Masters, and recommends that both should be read: even though the reader has little time and there are many more exciting books out there!

Nature (E. John Russell), 3 May 1947 (12” column): A very reasoned account of the book’s raison d’être and HW’s handling of it; praising the inclusion of Jefferies’ long letter to The Times and its subsequent crushing criticism in the Liverpool Mercury.

John O’London’s Weekly (John O’London, nom de plume – whom at this time not known), 31 October 1947: There is a whole page under the regular heading ‘Letters to Gog and Magog’ (mythical giants who were considered to be in the service of the devil): ostensibly it is a review of HW’s 1947 revised reprint of Selections, under the heading of ‘Jefferies as Prophet’; it gives a considered and wider critique of that concept, questioning its validity, and noting that HW had compared Jefferies with Hitler: ‘The description, I’m afraid, does not square with the facts.’ (And no, of course they didn’t in 1947: the words were written in 1937, when, although naïve, they were valid in the context understood by HW. Certainly both HW and his publisher Richard de la Mare should have realised the problem the phrase could create in 1947.)

His [Jefferies, but one suspects that the reviewer means equally applicable to HW!] desire to be a prophet did him honour. But in Jefferies the power of observation and feeling was greater than the power of thought. He may be for Mr. Williamson and some others the “prophet of an age not yet come into being”, but to many people his teaching will not seem to be true. That fortunately does not debar them from enjoyment of his best work.

I am, gentlemen,

Yours faithfully, John O’London

Sphere, 10 May 1947:

Richard Jefferies: Prophet

Richard Jefferies, essayist and observer of nature, was a lyrical and impassioned writer with a love and accurate knowledge of natural history. His outstanding work The Story of My Heart, has brought him immortality, but the Victorian world in which he lived labelled him as a mallard [sic – malade] imaginaire, a poverty-stricken neurotic. We now know better, realising that Jefferies was a prophet crying in the wilderness of the industrial age, the theme of whose whole work was the burning hope for a better, truer, more sunlit world for mankind. Henry Williamson has since his youth been devoted to the personality of Jefferies and now as Richard Jefferies (Faber & Faber, 8s. 6d.) he gives selections from his work and some further details of his life. This book will introduce Jefferies to a yet wider public, and in so doing does a service to literature for his prose belongs to our literary heritage.

*************************

Click on the link for illustrations of the various dust wrappers to the titles covered here.

*************************

Go to:

Richard Jefferies Centenary Celebrations, June 1948

Henry Williamson and the Richard Jefferies Society