THE GOLDEN VIRGIN

(Vol. 6, A Chronicle of Ancient Sunlight)

“Objects of hate are but our own chimaerae

They arise from wounds within us”

Father Aloysius

|

|

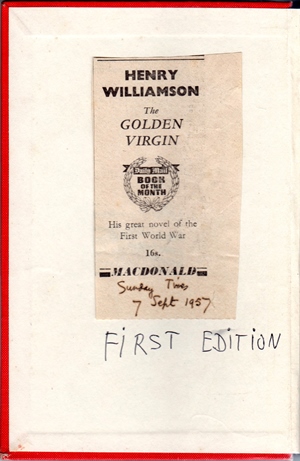

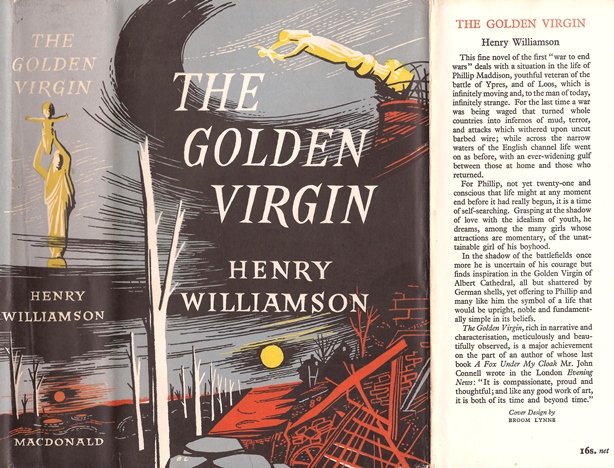

| First edition, Macdonald, 1957 | |

First published Macdonald, 6 September 1957 (16/- net)

Second impression, with some revisions, May 1961

Third impression, January 1966

Re-issued Macdonald, using sheets from the 1966 third impression, re-cased and with a new dust wrapper bearing an ISBN. Date not known, but probably 1970 or soon after, as that is when ISBNs were introduced in the UK.

Panther, paperback, October 1963, 5/-

Macdonald, reprint, 1984

Sutton Publishing, paperback, 1996

Currently available at Faber Finds

Dedicated:

‘To RICHARD ALDINGTON’

Richard Aldington (1892-1962) was a writer of note, although somewhat controversial. The two men were close friends. The first contact between them was in 1929 when RA wrote a complimentary letter on publication of The Wet Flanders Plain. His own very well received book Death of a Hero was published soon after. But there was no further contact until HW invited RA to contribute an article in The Adelphi when in 1948 he became owner and editor. But the two men were really brought together by Alister Kershaw, who admired both writers and went to work for Aldington. In 1949 Kershaw arranged for HW to spend his honeymoon with his new bride Christine at RA’s home at Le Lavandou on the south coast of France; and so began a steady friendship between these two eminent writers. Correspondence between them was extensive. The friendship was somewhat bruised however by Aldington’s revelations in his controversial book on HW’s rather god-like hero, T. E. Lawrence: Lawrence of Arabia: A Biographical enquiry (Collins, 1955). However, they made up their differences and the dedication here is HW’s public affirmation of their enduring friendship.

[For the full background see HWSJ 28, Sept ‘93, AW, ‘The Genius of Friendship, Part II: Richard Aldington’, pp. 7-23, and a further article by Kershaw, 'Henry Williamson', in same issue, pp. 24-33. This area will be more fully explored in the forthcoming page on Genius of Friendship.]

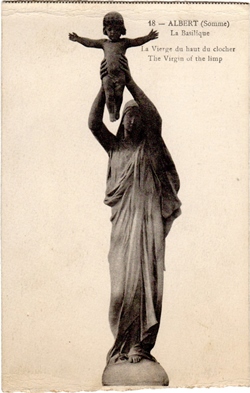

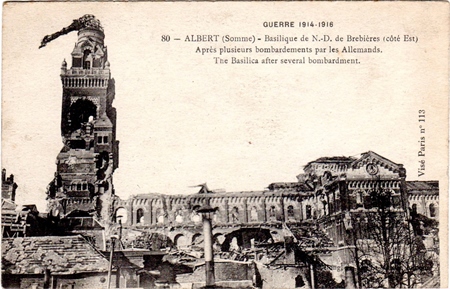

Placed in the front of HW’s own copy of this first edition are several items. One is this postcard of the Golden Virgin of Albert:

Another is the later Book of the Month wrap-around addition:

There are also two or three review cuttings which will be found in the Critical reception section, and these two watercolours, the first showing the basilica of Albert, with its leaning Virgin and Child; the other is dated 6/16 and initialled 'DNM' (?):

************************

Phillip has returned to England in the late summer of 1915, and as this volume opens is on leave, letting his hair down, to his sister Mavis’s jealous annoyance. He then joins the ‘Diehards’ Regiment where he proceeds with training, first at Hornchurch, then at Northampton and on to the Machine-Gun Training Centre at Grantham. This training is interrupted by further convalescent leave (during which he meets the tragic Lily Cornford) but orders arrive recalling him to report for immediate duty in France.

At Étaples there is further training for the forthcoming attack, with a great deal of detail included. Phillip is moved forward to Albert where he sees the symbolic ‘Golden Virgin’ – the legendary statue damaged by German shelling but still hanging from the church tower. His new C.O. is ‘Spectre’ West, who understands that the German defences are impregnable and that the forthcoming attack is doomed (on trying to point this out he is relieved of his command – but in the ensuing battle wins a decoration, adding a bar to his MC).

The attack – the Battle of the Somme – commences at dawn on the 1st July: a fine summer’s day. During the chaotic carnage, Phillip is wounded on the first day, lying out in No Man’s Land and later found by the saintly Father Aloysius. He is returned to England where he gradually recovers and goes down to Lynton in Devon to recuperate. Back in London the domestic scene continues with its own involved scenes of mayhem: the climax being the death of Lily Cornford (Phillip’s own ‘Golden Virgin’) from a Zeppelin bomb.

As this volume ends Phillip is due to return to Grantham to continue his interrupted training.

************************

This correction sheet, itself heavily revised, shows the extreme care that HW took over his writing – in a letter to HW, Victor Yeates, his schoolfriend and author of the classic Winged Victory, wrote, 'Writing is instinct: revision is skill'; and HW constantly – obsessively even – revised and re-revised all his work:

Piecing together the various sparse bits of information – clues – it is obvious that HW found The Golden Virgin a difficult book to write. There is little in his diary, but enough so that, with other sources to illuminate the struggle, one can piece the background together. The book needed a great deal of research (as had A Fox Under My Cloak) but mainly HW had to decide his story-line – how he was going to manipulate his characters and encompass as wide a view of the whole war as possible, both at the Front and back in England.

He also had to think ahead about the structure of the series as a whole. We know that from the earliest point he actually started to write these books (1948/9) he planned to encompass his time on the Norfolk Farm during the Second World War, because his first idea was to start at that point and make everything else retrospective; but his publishers (mainly through Malcolm Elwin) advised him to actually start at the beginning and work through to the end.

It is apparent that in early 1956 this flared up again. The main reason was possibly the product of an overworked mind, compounded by the fact that he was always convinced that he would die before the work was completed, and whenever his mind was in turmoil he would (albeit subconsciously) invent further complications. At this time, too, he had a huge falling out with Malcolm Elwin (who apparently now no longer worked for Macdonald). A diary entry at the beginning of 1956 reveals that Elwin was passing on to others information about HW’s personal life and, more importantly, his writing plans, which had been made in confidence. This brought to the fore a number of old grudges – including those about Susan Connelly, but more importantly here, that about the Norfolk Farm volume (variously called ‘Lucifer and Darkness’, ‘The Man who Went Outside’, ‘Wit’s Misery’ etc.).

So (one feels perhaps to spite Elwin!) HW now resurrected this MS/TS and was obviously working on on it at the same time as The Golden Virgin: a recipe for disaster. All this is apparent from a diary entry at the beginning of March 1956: one book is being typed by a lady at nearby Combe Martin, the other by Mrs. Tippett in Truro, Cornwall (his ‘official’ typist). On 7 March, finished work arrived from both sources. HW recorded: ‘Returned this afternoon from London, tired and confused.’

He had been to London to sort out the future structure of the Chronicle series with his publishers. Although they were willing and had accepted the farm volume, he had actually been advised by John Middleton Murry, prominent critic and writer, a pacifist who had run a ‘Community Farm’ in the Second World War and editor of The Adelphi magazine, which HW took over briefly in 1948/9, and who was hugely supportive of HW, and preparing at this time a major critical essay on HW’s work (see HWSJ 35, September 1999, for full background) and also by his long-standing friend John Heygate, NOT to publish the farm volume out of sequence as it would confuse readers. He was in a fraught frame of mind and could not make a decision.

Interestingly, it was his typist Elizabeth Tippett who ‘tipped’ the scales. She wrote to say that having typed up various versions of the farm book and the previous Chronicle volumes, she felt that HW should continue in sequence, as readers would not be able to comprehend the later Phillip without continuous build-up. HW commented:

Admirable criticism! . . . I’ve been yea-naying. Now I say, NAY. Let it be put away, & on with No. 6.

The next day he notes ‘Posted Chapters 36-41 (end) of Man Outside [i.e. the farm volume] to Mrs. Tippett.’!! But this book does indeed now get left to appear in its sequence in due course.

Apart from a later addition (see end of the year entry) the diary is totally blank until 11 October:

I finished the 1st draft of The Golden Virgin today. Felt a little relief. No: I finished some weeks ago, & rewrote the last bits today, & posted in afternoon to Middleton Murry.

Monday 22 October: Murry’s opinion of Parts I & II sent to him recently came this morning. I read it, dolefully, in the churchyard [Georgeham]. It is unfavourable. . . . Part I should be cut . . . he was severe . . . I recovered later, and planted some oak trees in the west spinney. . . . I think I’ll be grateful to Murry, because I shall condense & cut & that hurts nothing, considering that I wrote the book rather vaguely & only found out things as I went.

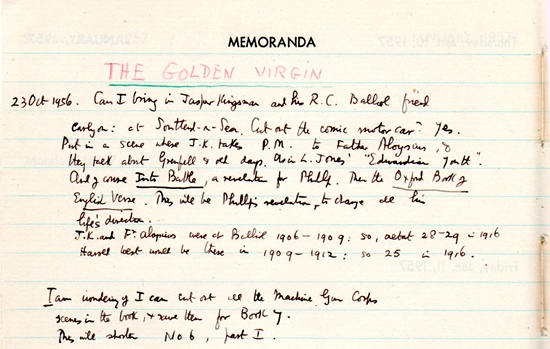

The next day he affirms: ‘. . . Jack is right. . . . See MEMORANDUM at the end of this diary for results of . . . ‘

He chews the problem over again in an entry added into April but actually written in retrospect from the end of the year:

. . . So I withdrew it [the farm volume] and went on with The Golden Virgin though I was tired and had planned to REST this year, & write the Bray Stream Book for Faber – most of which is already done. [This is A Clear Water Stream, published by Faber, 1958.] I wrote Virgin steadily, with seldom a break until October of this year. It totalled about 180,000 words & I was pretty stale all through & as I have recorded in passage of 22 October Murry read 2/3rds of it & reported that it was bad.

So it looks as though I have had 3 miscarriages this year, with Doctors Heygate and Murry in attendance, . . . & again when the Golden Virgin was apparently sterile and boring.

But it is actually obvious that HW himself had doubts anyway about the book. The fact that he sent it to Murry – and then accepted his criticisms very calmly – shows this. If he hadn’t felt that himself, he would never have accepted such criticism, and would have turned against Murry just as he did Elwin.

Serious researchers consulting the manuscripts held at Exeter University Special Collections Department will find the various versions of this volume (and of all the Chronicle – and indeed HW’s entire oeuvre) reveal all the various revisions. HW was a perfectionist and reworked his material, almost obsessively and often unnecessarily, until he felt it was right.

Letters between HW and Murry reveal further detailed discussion about the book (see HWSJ 35, September 1999, AW, ‘Millenium Revelations: John Middleton Murry’, pp. 38-66, see p. 60-61). But Murry was now a very sick man, and he died on 13 March 1957. HW attended his funeral at his home in Thelnetham (near Diss, Suffolk).

His last letter to HW, written on 11 December 1956, had been finally encouraging about the new version of The Golden Virgin:

What you tell me of the new beginning – Tollemere Park, Father Aloysius, and the words on Ching – seem good to me: gives me the feeling it belongs . . .

HW later wrote at the bottom of this:

My dear Jack, you were to die three months after sending me this letter. I wish you could have seen the story as it is now, due (the vast improvement) to both you and Elwin. You, and he, both went far out of your different ways to be kind to me, Henry, 27 March, 1957

With the problems all satisfactorily solved, HW had reverted to an equanimity of mind. One deduces here that the final version was ready to be sent off to the publishers.

(John Murry’s important critical essay on HW’s work (up to A Fox Under My Cloak) was published first in shortened version in The Aylesford Review, Vol. 11, No. 2, Winter 1957-8, a special edition devoted to HW’s work – see below; and in full version in the posthumously published Katherine Mansfield & Other Literary Essays, Constable, 1959. The essay, The Novels of Henry Williamson, has been also been published separately as an e-book by the Henry Williamson Society, and is available from Amazon, iTunes, or directly from the Society.)

Diary entry 6 September 1957: ‘The Golden Virgin published today.’

But the occasion was marred. HW had been in Ireland since 28 July, camping in the Countryman but at this point staying as guests of John Heygate at his home on the Bellarena Estate. The day after publication HW went into the nearby village, Limavady, to collect copies of the Daily Mail, which he knew was publishing an article on him by Kenneth Allsop (well-known writer and broadcaster, and close friend). To his horror, he found that Allsop had written that HW had been awarded the Military Cross aged 20 – apparently having mistaken the ribbon of the Mons Star on a photograph of HW pinned up in his Writing Hut for that of the MC. HW was extremely upset that such a false statement should be published in case it would brand him a liar. Allsop was of course basically a journalist and such a good story line prevailed over verified facts (note Allsop’s own tale that his right leg was amputated due to a flying accident in the war, when in reality it was due to a tubercular bone going back to childhood). On HW’s return to England a few days later he received a letter of apology from Allsop, saying he should have checked his facts (but I don’t think it was ever publicly retracted). This caused a coolness in their friendship for a long time (in fact it never really stopped rankling, and surfaced in HW’s thoughts from time to time).Allsop's review is included in the Critical reception section.

(See Mark Andresen, Field of Vision, 2004 (but where several facts about HW are incorrect) and AW’s review of this in HWSJ 40, September 2004, pp. 95-6. Also HWSJ 28, Peter Robins, ‘Adventure Lit His Star’, pp. 34-9; and HWSJ 29, ‘Steepholm, the K.A. Memorial Trust’, letter, pp. 62-3.)

************************

Soon after this HW moved into a proper house again. Life in a caravan at the Field with wife and child had become a problem. On 23 November 1957 HW noted: ‘Posted cheque to [solicitors] for purchase of No. 8 Brittania Row £86.’ This was one of a row of houses (narrow but tall!) in the nearby town of Ilfracombe, where HW lived for the rest of his life. The Field and his Writing Hut reverted to his refuge for peace and quiet.

On 3 October 1957 HW was made a FRSL (Fellow of the Royal Society Literature), and his diary notes: ‘Very happy day for me’. This was a high literary honour reserved for ‘persons of distinguished literary achievement’, and was not given lightly. On 1 December 1957 (his sixty-second birthday) he was also made an FIAL (Fellow of the International Institute of Arts and Letters, which is based in Zurich).

HW’s diary entry for 12 December 1957 shows that he met:

Father Brocard Sewell with whom I’ve exchanged letters about the G.V. & other books. [At dinner at his daughter Margaret’s in London.] He is producing a Winter number of Aylesford Review, dealing mainly with H.W.

This work duly appeared in late January 1958 when HW noted:

The copies of the H.W. number of Aylesford Review arrived. Splendid, kind, warm number.

However, HW took great exception to the essay by Malcolm Elwin, because Elwin used material which HW had given him in confidence (mainly the Norfolk Farm typescript), which HW did not want publicised then as he had decided to hold that for later (as previously explained). Several file copies at that time had very irritable comments about Elwin and his methods!

Fr Brocard’s editorial ‘Henry Williamson’ opened:

We direct our readers’ attention to the works of a great living writer, the maker of many beautiful books, Henry Williamson.

Father Brocard Sewell (an assumed name taken when he entered the priesthood post Second World War) was a Carmelite friar based at Aylesford in Kent, and editor of the erudite literary journal The Aylesford Review. This was the start of a firm friendship between the two men, and Fr Brocard always did all he could to promote HW’s writing. There is a large file of the correspondence between them held at Exeter University, which contains many literary details of interest to researchers.

HW attended various literary meetings organised by the Review (held at Spode House, near Rugeley, Staffordshire, run by the Carmelites) which he always greatly enjoyed. After HW’s death, Fr Brocard organised a Symposium of writing in his honour, with contributions covering the various aspects of his writing (Henry Williamson, The Man, The Writings: A Symposium, ed. Fr. B. Sewell, Tabb House 1980; copies available directly from the Henry Williamson Society).

************************

The Golden Virgin is divided into three parts: Part One, ‘The Wild Boy’; Part Two, ‘The Somme’; Part Three, ‘The Quiet Boy’. These immediately reflect the structure and content for the reader. However, things are not quite as simple as that. The outline overall story line is straightforward, as the above shows, but HW weaves a complicated tapestry in the making of his magic carpet, as will become clear.

Part One, ‘The Wild Boy’

As the book opens it is late autumn 1915 and Phillip is on leave at home, having returned from the Front (and the aftermath of the Battle of Loos) to join the ‘Diehards’. This was the actual familiar name given to the Middlesex Regiment: HW made a correction note to change that to a fictional ‘Standfast’, but that never happened.

Phillip is shown ‘letting his hair down’ at the Gild Hall with his friends Desmond and Eugene, to his sister Mavis’s jealous annoyance, who tells tales embellished to actual lies to their mother. Mavis is now working in the Head Office of the Moon Insurance Company (Phillip's firm). (In real life HW’s sister Kathy actually worked in the same bank as their father.)

Other local worthies are also looking out for trouble: Detective Sergeant Keechey and his mate, unpleasant plain clothes detectives who are officially on the look-out for deserters and spies.

We learn that Tom Ching, a singularly unpleasant character (the wretch was based on a real person), is running after Mavis. He is the unsavoury type whose main purpose in life is to dodge service in the Army (but with no real pacifist conviction).

Phillip’s only relief from the reputation of cowardice and wastrel that circulates among his family and the locality of Wakenham is a letter that arrives from ‘Spectre’ West, praising Phillip’s actions at the Battle of Loos (where Spectre wounded, and was awarded a bar to his MC).

|

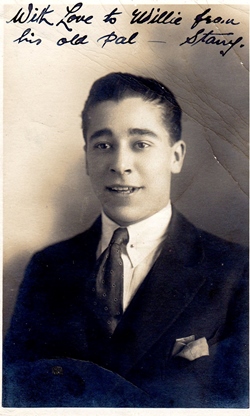

| Eugene Maristany |

|

|

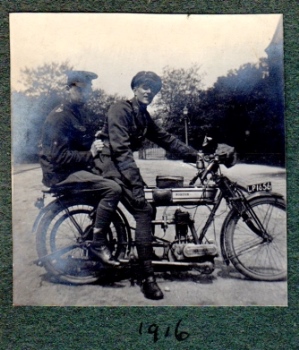

| HW and his friend Terence Tetley | |

Due to report to his new posting at Hornchurch, Phillip, finding his beloved motorbike had a flat tyre, recklessly buys a Swift ‘runabout’ and he and Desmond set off for Hornchurch – ‘Grey Towers’, east of London and north of the river; they drive through the Blackwall Tunnel. (There is no indication that HW actually had a Swift at this time: but this cameo shows his great interest in sports cars, which remains a potent thread running through his life and his books as time goes on.)

Phillip’s mood is optimistic as he settles in, but of course it evaporates. He reads a letter from Granpa Turney warning him against drink – the fate of the syphilitic Uncle Hugh looms over Phillip and any hint of dissipated behaviour at regular intervals. (This letter actually exists, though it was in real life written later, after the war had ended.)

Phillip is in Captain Kingsman’s company. Soon after his arrival, Kingsman asks Phillip to drive him to Southend to inspect a detachment of the company. These turn out to be blind men – who strange though this may seem, were indeed used as lookouts, their other senses being enhanced – and then to spend the night at his home.

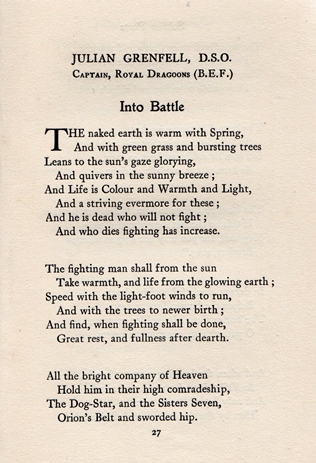

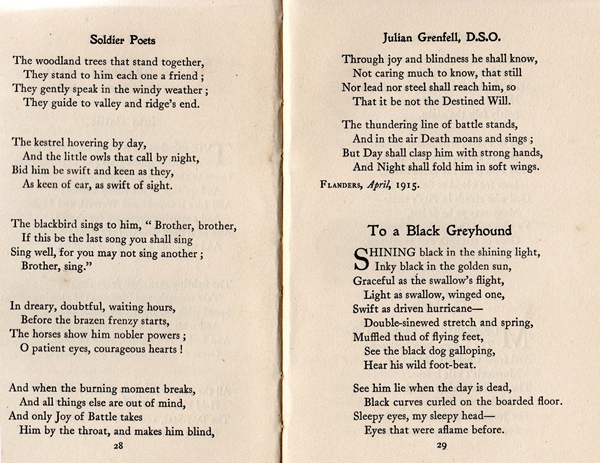

This is a large country house, very formal, and Phillip feels there is a strained atmosphere. Father Aloysius arrives, and his conversation reveals that the Kingsmans are very well connected, and know the Asquiths (Herbert Asquith being the Prime Minister), and gradually we learn that their son in the RFC uniform, whose portrait on the wall intrigues Phillip, has recently been killed. Phillip is asked to read the poem Into Battle by Julian Grenfell (killed in action May 1915). And we learn later in the novel that Fr Aloysius’s actual name is Llewellyn Vaughan-Herbert.

This cameo piece is rather obscure and, although the reader does not need to know the background, it does enhance understanding to have it explained. HW is presenting something that otherwise would not have impinged on Phillip’s world at that time. Through the medium of the Grenfell poem to record the deaths and pay homage to a set of quite brilliant young men, friends and fresh from university, many being titled sons of the aristocracy, whose lives were cut so tragically short and about whom little is now heard (they were but a few among so many who gave their lives); they include Raymond Asquith, the son of the Prime Minister, Rupert Brooke, and in particular here the promising poet Julian Grenfell, the brother of Lady Monica Salmond (their parents were Lord and Lady Desborough). Grenfell’s poem is printed in Soldier Poets published during the war, of which HW had a copy), and he may also have seen it when it was printed in The Times in its report of Grenfell’s death in May 1915. The poem certainly meant a great deal to him. At the time HW was writing The Golden Virgin he was in close touch with Monica Salmond (and was indeed godfather to her grandson).

Grenfell, who treated the war as a glorified picnic, going out into no-man's-land stalking and shooting German snipers (he died before the Battle of Loos, the debacle of the Somme and the dreadful attrition of Passchendaele, after any of which he may have modified his views), was hit in the head near Ypres and died at a hospital at Boulogne on 26 May 1915, nursed by his sister Monica.

(Fuller research into the background here can be found in HWSJ 34, Sept. 1998, as part of Anne Williamson, ‘Some Thoughts on Spectre West and other elusive characters’, pp. 86-94, particularly 88-92. The background to the portrait of the RFC pilot is also examined in this article. It is clear from letters between Monica Salmond and HW that Grenfell forms a large part of Spectre’s persona.)

There is now an obvious connection from this passage to the quotation from Margot Asquith (the Prime Minister’s wife) at the beginning of this Part One, which is otherwise possibly puzzling. Her son had been killed by the Germans, but her message is of reconciliation. The Hamlet quote which follows furthers this theme, although not so obviously. (HW’s personal empathy with Hamlet is discussed in the page on The Gold Falcon, published in 1933.) Reconciliation is a huge underlying theme within the Chronicle, and one that should not be underestimated, which becomes obvious in the final volume, The Gale of the World.

Mainly, this scene brings into prominence the shadowy Father Aloysius, who is an important thread in the Chronicle. Like Spectre West, this character does not seem to exist in real life as a separate entity, and is a complicated composite. He is used by HW to show tolerance and compassion and reconciliation – as the quotation on the title page of this volume reveals:

'Objects of hate are but our own chimaeræ. They arise from wounds within us.'

These words can be found on page 75 of The Golden Virgin in a paragraph well worth reading for its overt and covert message. As Father Aloysius does not exist, his words are directly attributable to his creator, HW. However the last words of the great Indian leader Mahatma Gandhi (who died in 1948) were very similar:

The devil is in our own hearts and that is where we must fight him.

Gandhi was a proponent of love and peace (in effect a pacifist). It would be typical of HW to transmute those words to illuminate his own purpose. By its prominent placing on the title page, it is certainly a thought HW that wanted his readers to ponder: they echo words spoken in an earlier age: ‘Love thy neighbour.’

After Phillip reads Grenfell’s powerful poem Into Battle and Fr Aloysius says a prayer, he ‘felt himself to be small and simple and blessed’. Phillip had had that exact feeling in the presence of Mother Ambroisine when he visited the Thildonck Convent in Belgium as a young boy. His sister had attended that convent and of course the current fighting is on Belgian soil – so there is a multiple association, a linking of thought. Father Aloysius tells him that his sister loves him (contrary to all the evidence against that!).

After this scene Phillip is seen to have become more mature and to have a better understanding and tolerance of life’s problems: although the reader may not necessarily realise the source of this.

Life at Hornchurch is shown as somewhat squalid, but immediately Phillip is seen to have matured as an officer (and thus as a man) as he deals with the navvies who are the raison d’être of the unit. ‘Navvies’ were manual workers, so named originally for digging out ‘navigation’ canals, now on trench defence work, who tended to be rough, and the scene involving them is in marked contrast to the weekly over-genteel ‘social’ soirée of the officers.

Phillip goes up to ‘Town’ (London) where he meets two girls, Frances and Alice. Frances is (rather too fortuitously) the cousin of Spectre West. These young women typify the era, revelling in the sudden freedom of behaviour allowed women due to the war. Phillip rather falls for Alice. But just before Christmas a new battalion is formed at Northampton, and the chosen men move on: Phillip shares lodgings with his new friend Captain Bason, and they invite the two girls to visit.

|

|

On the reverse of this photograph HW has marked: top left: 'Phillip M.' [HW, of course]; front row left: 'Flagg the Grimsby fishmonger'; middle front: 'Captain Bason'; the other two: 'not used' |

The battalion is moved out to a camp for a Lewis Gun Training course (following HW’s own experience). Going to Town on Christmas Eve to see Alice, Phillip finds her with another man. He returns to camp despondent, and his thoughts turn (as HW’s always did) to the Christmas at the Front the previous year:

Now the lighted fir-trees would be on the parapets, voices singing Heilige Nacht. Why was he not there . . . While he lived in memory upon the frozen battlefield, where the morning star shone white and lustrous in the east. . . .

This is sharp irony. Fraternisation that year had been forbidden: the authorities dare not let such events happen again, for it undermined the act of war. As Phillip later learns from a letter from his cousin Willie, British guns were ordered to fire at 7 p.m. on Christmas Eve and blasted the German ‘Holy Night’ festivities.

Phillip is now posted to the Machine Gun Training Centre at Grantham: two months learning Vickers Mark Ten gun use – then Riding School (all following HW’s own routine). When fully trained he expected to be a Transport Officer within a company.

On weekend leave Phillip goes down to London and buys suitable new kit, the ‘permitted’ field-boots, breeches, and spurs. He collects his beloved motorbike, leaving the Swift behind, and makes a brief visit to his parents, making more sympathetic contact with his father. His mother feels he has matured.

Phillip returns via Beau Brickhill to visit his cousin Polly (with but one purpose in mind) and finds Percy on leave, also wearing breeches (which Phillip realises are unsuitable), as his father wants him to go into the transport division. That night Polly does indeed come to Phillip’s bed.

Arriving late back at Camp, Phillip reports sick and is given leave – ‘to rest’. Back home again (to surprise and suspicion) he finds Desmond and Eugene in Freddy’s Bar, with a girl with

large blue glistening eyes and loose smiling mouth, tall white neck and golden hair coiled under straw hat with a spray of forget-me-knots circling its dark blue crown

– the delectable Lily Cornford.

Also in the bar is the malevolent Detective Sergeant Keechey, watching Lily and his other suspects, including Philip, whom he has decided is a deserter.

Freddie's Bar was The Castle, run by William Frederick (Freddie) Coates:

Phillip’s 21st birthday approaches (April 1916 – HW’s real 21st was on 1 December 1916). His father wants to give him a signet ring, but when Phillip wants to have it engraved with the Maddison crest, Richard is totally against it and refuses to have anything to do with it. Thus empathy between father and son again destroyed. Granpa Turney takes charge instead, giving both signet ring and a cigarette case (with the Turney crest) – poor Richard! All these difficult family interactions are very well handled: all are given faults and virtues, and there is throughout a solid portrayal of real family life.

Tom Ching is called before the ‘Tribunal’ to hear his appeal against being called up on grounds of conscientious objection (to war) – another social factor brought into the story. His claim is refused as false (as are several others).

Phillip meets up with Lily (shaking off the clinging Ching). He recites Grenfell’s poem to her which moves her to tears, and she confesses that Keechey had raped her when she was fourteen years old, resulting in an abortion. Lily is portrayed with great sympathy as one who copes with life’s circumstances as best she can, while with a sensitive nature. But Desmond gets to hear of their meeting and takes great offence, while Mavis’s unpleasant persona is furthered by her truculent demand for money from their mother.

Phillip, having over indulged drink on his birthday (and cut the family celebration to do so), goes to see Dr Dashwood, who finds a dull patch on his lung, and he is sent to Milbank Military Hospital. Again HW makes out that Phillip is a malingerer, which is very unfair to Phillip – and to himself. HW was still very far from fit and was admitted to Milbank Military Hospital at the end of May 1916 for a month, and then given two months’ convalescent leave (see AW, Henry Williamson and the First World War, p. 59). No malingerer would have been tolerated or indulged with such treatment: more likely a court martial would have resulted.

Phillip is also given two months’ convalescent leave (note that the timing is ahead of HW’s actual experience), which he plans on spending at Lynton in North Devon, at his Aunt Dora’s cottage. He prepares his ‘three-piece hickory’ fishing rod: ‘It was a fine morning in the second week of May.’ The garden is coming towards its perfect state, blossom out, the apples beginning to form, BUT as he remembers childhood delight in stealing those apples with his pals,

Never, never again! Gerry and Bertie, Tommy and Peter, Alfred and Horace, and the boy he was, never the same again, for tree or man or bird.

[i.e. his Cakebread cousins, Tommy Atkins, Peter Wallace, Alfred Hawkins, and Horace Cranmer]

A cry for that lost boyhood, cut off so abruptly – so totally for many of his friends – as his poignant words at the end of his ‘Boy’s Nature Diary’: ‘For ever, and for ever, and for ever.’

The convalescent holiday in North Devon does not happen. A telegram recalls Phillip to report for duty, finally triumphing over Keechey (who meanwhile is known to have attacked the naive Dr Dashwood because he thought he was involved with Lily), who thought it was a summons to appear before authority. (In real life the person on whom Keechey is based was in due course sent to jail, as a cutting in the archive reveals.) Phillip knows that this means ‘The Big Push’ is imminent, and says his goodbyes to family and friends. Desmond, knowing Phillip has been with Lily, whom he considers his girl, is bitterly vicious, saying he hopes Phillip is killed in France and doesn’t come back.

HW sends Phillip back to France to prepare for the Battle of the Somme. In real life HW came out of the Milbank Military Hospital after a month on 26 June, and was given two months’ convalescent leave. He was extremely lucky not to have been involved in that hellish battle, with its huge loss of life and little chance of living through it. But to achieve his purpose of showing as wide a panorama as possible of the war, this major event had to be included. His structural device and faultless ingenuity, together with his writing skill, manipulates the material with meticulous technique. The reader lives within the scene with vivid clarity.

Part Two, ‘The Somme’

As they cross the channel they hear the noise of what Phillip thinks must be a naval battle: this is the massive Battle of Jutland on 31 May/1 June, which resulted in huge loss of British life and ships. The result was inconclusive (though both sides claimed ‘victory’), but the Germans had to rethink their naval strategy (which resulted in unrestricted submarine warfare). But this was a very clever way to bring that event into the story.

Phillip is told to report to Étaples, where the training for the forthcoming attack is described in some detail. After three days the men are moved on to various regiments (quite stupidly arbitrarily, as in real life, causing considerable disquiet in the ranks). Phillip is sent (very fortuitously) to Querrieu to join the regiment he had been with at Northampton, currently out of the line, where he finds Kingsman is acting CO, with Milman as Adjutant, and Captain Bason and others.

He reads the current orders, catching up (and allowing the reader to become acquainted) with information about the forthcoming attack – ‘The Big Push’. Grenfell’s poem is constantly flashing through his mind.

The men practice over an area representing the section they will be attacking. They also play cricket, football, run, and box: all keeping the men occupied and fit. Phillip goes to a concert got up by the men where, unbeknown to him, Father Aloysius is present, who is padre with an Irish battalion. The men are marched off towards Albert. Another little nugget of history is included when they hear that Lord Kitchener has been drowned on his way to Russia: his ship has hit a mine.

Phillip is shown developing a good rapport with his men as we come to the central theme of this volume:

Phillip lay near his men, listening to the singing of larks through the thud of howitzers, the remote corkscrewing of shells travelling east into the height of the sky. Poppies shook in the evening breeze, with marigolds and scabious. Below the hill, to the north-east, lay the ruinous town of Albert. . . . a large building with a campanile with something upon its summit glinting in the western sun. Focusing his field-glasses upon it, Phillip saw a figure, which once had been upright, but now was, upon its iron frame, inclining downwards at an angle, so that the object held in the figure’s arms seemed about to drop into the void below. . . . seen by all going into the line [and inspiring] the legend that the war would end only when the Golden Virgin fell into the ruins below.

Immediately following this ‘set-piece’ on this great symbol of hope, there is an exposition on water engineering: a vital component for the men and their horses and mules.

‘A’ company (8th Division) goes into the trenches nearly two miles north-east of Albert. They are just north of the long straight (Roman) Albert–Bapaume road, with the German front line on a rising slope just in front of the villages of Ovillers (in Mash Valley) and La Boiselle (in Sausage Valley) as these deadly areas were familiarly named.

Phillip is sent out on a raiding party to get prisoners from the German trenches, which to their surprise they find empty, one man only taken as prisoner (and he commits suicide before he can be questioned). On reporting back Phillip is taken to the colonel:

A figure with a black patch over one eye . . . a black hand . . . and a silver rosette upon the riband of the Military Cross.

It is ‘Spectre’ West, who astutely questions Phillip closely about the raid, realising that the Germans must have had pre-knowledge of it (and the implications of that); also on the crucial point of the depth of the German dugouts – and angry because the significance of such knowledge has not been grasped by the Staff: if deep, then the battle plan will prove useless.

Phillip decides it might help if he investigates the sappers’ underground galleries made for mine-laying: the complicated, dangerous and vitally important preparations for the mines under Y-Sap and the massive (famous) ‘Lochnagar’ under the Schwaben Redoubt (ten such mines were laid along the length of the whole Front). Silence is imperative. So difficult is this tunnelling work that the Official Record states: ‘An advance of 18 inches in 24 hours was considered satisfactory.’

HW’s research into this whole set-up prior to the opening offensive of the Battle of the Somme was meticulous. Every detail is correct. His basic material is taken from the 1916 volume of The Official History of the Great War (those volumes he had bought in October 1954 while writing A Fox Under My Cloak) but he used various other sources as well, and certainly first-hand accounts from men he knew. He weaves all this information seamlessly into Phillip’s life, with total reality. The reader is there in the harsh chaotic nerve-wracking tension and cheery comradeship that preceded the ‘Z-Day’ attack on 1 July. Much of this information is common knowledge today, but not really widely known at the time of HW’s writing.

Phillip decides that the German dugouts must indeed be deep, but this is not good enough for Westy, and he plans a further raid into the German trenches to find out exactly. They discover that the German front line is held in strength. They are unable to investigate the depth of dugouts but Phillip now deduces that they are pretty deep. These facts are crucial to the coming battle: Westy knows that what they have found means the attack is certain to fail.

Chapter 16, ‘The Yellowhammer’, covers a final rehearsal for the forthcoming assault. This takes place over French farmland: the French cultivateurs are furious that their crops are destroyed: one calls the English ‘les autres Boches’, again based on fact. This man then shoots a yellowhammer. (There is a distinct resonance here to a similar incident in HW’s short story ‘The Ackymals’,when John Kift shoots two marsh-tits. However one needs to realise that a yellowhammer would actually mean food to a Frenchmen in the middle of this war.)

The rehearsal goes well:

Unimpeded, irresistible, the division went forward in six waves, up slowly rising ground to the final objective, a large white notice board on which was painted in black letters

SITE OF POZIERES

The irony here is of course unmistakeable. HW’s writing skill placing the barb very cleverly and subtly. There was nothing to impede, to overcome – the notice-board was just an inanimate object. It could not blast the men with horrific barrage. The men were lulled into a false sense of security (though possibly this was just as well). Immediately after this, we learn that Colonel West has been removed from his command. Spectre had reported his unpalatable truth about all the envisaged problems to his immediate Commander, General Rawlinson. Rawlinson did not want to know, so West was removed. This is a prime example of Spectre West’s character being used to show the problems of lack of reconnaissance and communication.

Proceedings had been watched by Field Marshal Sir Douglas Haig. We read his views in an aside within the flow of the story line, and we learn further what has happened. It is all cleverly done, and we are hardly aware how that important information has been imparted.

So the waiting continues, with British bombardment intended to confuse the Germans about the timing of the forthcoming attack. Phillip is appointed ‘Pigeon Officer’, so encapsulating an important aspect of communication at the Front (although this is not really carried through and examination of typescript versions might reveal that text cuts in the text were made). In another ‘aside’ we learn that the Germans know all the details of the forthcoming attack. The final preparations are made, as the men go into the front line carrying picks, shovels, bombs etc. All was ready,

as in the last night of June the company paraded silently, while the croaking of frogs in the wide marshes of the Ancre became insistent.

[See also The Wet Flanders Plain, where in 1925 HW hears those frogs again and remembers how sinister they were.]

The men march off through Albert, passing under the ‘Golden Virgin’. Phillip’s thoughts are chaotic, but he calms himself by reciting Julian Grenfell’s poem Into Battle and thinking of all those already dead (i.e. brave enough to die).

General Rawlinson added the final nail into the Somme coffin by telephoning a message of good luck – overheard by the German listening post, thus confirming the exact moment of the attack they were already thoroughly prepared for.

As the fearful bombardment begins, back in England Richard Maddison, out on the Hill on a beautiful summer’s day in England, hears the rumbling, and thinks how splendid it all is.

The Battle of the Somme continued for 140 days; 140 days of relentless fighting; 140 days of death and horror. With gritted, relentless determination the Germans were driven back about six miles. The battle was finally halted on 18 November. Total British casualties, dead and wounded, were 420,000 (nearly 60,000 on that first day), French casualties 203,000; German, 437,500: over one million in total.

Having set the scene with such harrowing accuracy, HW did not labour his writing on the battle itself. Phillip is one of those wounded on the first day. Collapsing unconscious, as he comes round he finds Father Aloysius there calming him. Phillip is seen now thinking of others rather than himself. Much later he manages to crawl back towards the British line.

At one period on the crawl back he seemed to be hearing the bell-like colour of wildflowers with startling clearness – field scabious, poppies, marigolds, small pansies . . . about the flowers were wild bees and grasshoppers, scarlet soldier flies and bronze beetles among the grasses. They glowed and shimmered with varying sounds and colours . . . it did not last long . . . pain returned.

A bitingly poignant and surreal description of what was in actuality a nightmare of ruin and disaster: a mini master stroke which should not be overlooked. We should not underestimate how many hours went into getting that small scene to such a pitch of perfect imagery.

This scene is reprised as it really was towards the end of the volume in another master stroke of structure, when Phillip is talking to Mrs Neville:

To her surprise he broke into tears; but almost immediately recovered. He did not tell her what had caused him suddenly to break – a vision of thousands of still figures lying in Mash Valley as he crawled away from his dead platoon on that afternoon of intolerable sunshine.

Phillip is found by a stretcher party and sent first to the CCS (Casualty Clearing Station) at Heilly and then to the Field Hospital at Rouen, where he learns that Captain Kingsman and all the brigade have been killed. After basic treatment he is sent back to hospital in England. He has survived. And it is that element that was to drive HW for the rest of his life: he had survived – and must speak for those millions who had not: to try and prevent such horror ever happening again.

The mood is lightened on the hospital ship across the Channel, when Phillip picks up some old copies of magazines, and scrawls scathing comments across the advertisments. It is partly through the inclusion of such small, authentic details as these that HW recreates the past so vividly for his readers. One such was for the 'AutoStrop' razor, in Nash's and Pall Mall Magazine:

So the intense theme and mood passes into:

Part Three, ‘The Quiet Boy’

Richard, working at his allotment, has a visit from a concerned Lily Cornford – the Vision, as he thinks of her. Lily continues, and nervously calls on Mrs Neville as Desmond has also been at the Front and is wounded. Mrs Neville understands her and the two women become friends. Lily is trying to put the past behind her and make a fresh start. She is sorry that she has come between the two friends, and does not want to see either of them.

We also catch up with Captain Hilary Maddison, Richard’s older brother: he has been torpedoed, but has accumulated money through war investment, and now plans to buy back the family land sold by their father. We learn that Willie has also been wounded (in the attack on 14 July) and is also in a London hospital. This is laying down pointers that will have significance as the plot later develops: HW knew how he was going to develop his story in future volumes. The two brothers also discuss their German heritage and condemn the Germans for their cruelty and sentimentality – an interesting little exchange that is easily missed.

Phillip has a letter from Spectre (also badly wounded and in hospital), which conveniently explains the battle strategy and why it has failed: a neat – though obvious – device.

When Phillip recovers he is sent off by the redoubtable Georgiana, Lady Dudley – thus bringing into the picture the work done by those titled women who worked tirelessly for the wounded, and of whom we learn more later – to convalesce at Sir George Newnes’ home, Hollerday House, on the cliffs at Lynton. (This was a real place, but had actually been burnt down just before the war – so this scene is entirely fictional.)

After a short period at home Phillip travels to Devon, along with his sister Doris and Cousin Polly (in a separate carriage!) who are to stay with Aunt Theodora at her cottage in Lynmouth. They are to be joined by Willie, also convalescent, and Percy, on leave before he is sent to France. On the train Phillip reads with great excitement that ‘Lieutenant (temporary Major) H. J. West, MC and bar’ has been awarded a DSO for his bravery in the attack on 1 July. The demoted Westy has been vindicated.

Once again Phillip and his small party take that narrow gauge train from Barnstaple to Lynton, to be met by Aunt Dora, pleased to have the young people with her. Phillip is taken off (with humorous detail) to Hollerday House, from which he escapes as soon as possible. Down at the cottage, Dora notices immediately that Doris is in love with her cousin Percy:

An honest, rosy-faced country boy, a little slow perhaps, and an ordinary mind, but that was all to the good; there was enough nervous tautness already in the family.

Dora muses (to herself) on the causes of war, ancient and modern. She talks to Phillip, finding him receptive. And we have here a little ‘motif’ of the River Lyn – that symbolic thread running through the Chronicle series:

Was her mood taken from the running noises of the stream below, the water everlastingly hurrying, blindly, despite its clearness . . . to the sea, its blind parent . . . ever set upon its task of reducing rock to sand, and sand to dust. Water in the end wore away the hardest stone.

Deeply within her, Dora was afraid of her cottage . . . an indefinable remote dread haunted her, as though the Erinyes, avenging spirits of twilight, dwelt in the dark glen above the village.

That, in retrospect, chilling passage reveals that HW knows by then (1956/7) exactly how he is going to end his magnum opus – and I am sure he had indeed made that decision at the time of the disastrous natural event (the Lynmouth flood of August 1952) that encompasses the climax, still many years ahead of this point in the Chronicle.

Now re-introduced into the tale is the most extraordinary character, who appeared briefly at the Front: Lieutenant Piston, supposedly shell-shocked and wild to the point of (feigned) madness. Piston (and another equally strange character, Bill Kidd) was based on a friend of HW’s, Bill Child – who was possibly even more wild in real life than HW’s created fictional persona! Piston’s main histrionic act, having learnt that he is to be sent off to Scotland (though not named, this would have been the famous Craiglockhart Hospital where Siegfried Sassoon and Wilfred Owen were for a while, and which led of course to Owen’s outpouring of poetry), was to set fire to Hollerday House. His ploy worked. He was in due course invalided out of the Army – and out of the tale until the very last volume.

On Phillip’s return home he plays tennis with Helena Rolls. Milton arrives (an ex-Colfeian headboy – a nice touch!) and later at a St Simon’s Parish Hall dance, just as he thinks he is getting somewhere at last, Phillip learns that Helena and Milton are engaged.

Meanwhile Cousin Polly has come to stay – and announces, to Phillip’s total consternation, that she is pregnant; but Mrs Neville soon sorts out that tarradiddle! But as he goes back in great relief to his own house, the news has arrived that Percy has been killed in action at the Battle of Flers on 15 September 1916. Polly returns home. Doris is heartbroken. And later that night Phillip thinks of

the grief that must now be felt even by the walls of Brickhill House.

HW’s cousin Charlie Boon was killed in action at the battle at Beaumont Hamel on 16 November 1916, aged 21. [Details can be found in HWSJ 43, 2007, AW, ‘Cousin Charlie: A Tribute’, pp. 94-104] The HWS has visited his grave and made due tribute to this young lad, so typical of ‘every soldier’.

Phillip meets up with Tom Cundall, now a pilot in the RFC (HW’s friend, Victor Yeates) and hears all about the problem of Zeppelin raids now prevalent on London: again a useful device to bring this into the story, another social detail woven into the tapestry. He then goes round to Lily Cornford’s home and talks to her mother, who tells him that Lily will be home the following Saturday, 23 September.

On that day he goes up to stand outside Buckingham Palace when Spectre West is to be awarded his DSO, and afterwards is asked to join him for lunch at the Café Royal, where the rich food and drink are too much, as always, for his stomach to deal with. Later he meets Lily, firm in her intention not to become the bone of contention between the two men, now determined to become a nurse and to put the past behind her. He then goes off to meet Desmond and Eugene.

Later that night there is a Zeppelin raid warning. We learn that the pilot is the famous Kapitanleutnant Mathy. Going out on the Hill to watch out with Desmond, the latter argues about Lily, dragging up every fault against Phillip that he can think of. He is possessed by jealousy. Later they make it up, but at that moment the Zeppelin appears. HW’s dramatic description takes us to the climax: a bomb is dropped but then the airship is shot down. The two men go to find the damage. The bomb has fallen on Nightingale Grove – on Lily’s home: she and her mother (and others) have been killed. They help with the wounded. Richard Maddison was on duty and gets slightly injured, and later Phillip collects his father from hospital (another mark of increased maturity).

[This is based on a true incident – except that HW was not present. The background to this Zeppelin raid can be found in AW, Henry Williamson and the First World War, pp. 62-4. There is no evidence that HW actually knew the girl on whom Lily Cornford is based, Lily Milgate (although Terence Tetley may have done), but HW wanted to include this tragic happening in his tale.]

The next day Phillip and Desmond drive out to see the wreckage of the stricken Zeppelin at Snail’s Hall Farm (a real place): the pilot was not Mathy, although he was shot down soon after (in real life by Second Lieutenant Tempest, though HW attributes the feat to the amazing Tom Cundall). Phillip attends the funeral service of this pilot, rather than (although thinking about) that of Lily, also being buried that day. His own ‘Golden Virgin’ (that she isn’t is no fault of her own) has gone. He continues to Tollemere Park, home of the Kingsman family, to pay his respects and condolences to Mrs Kingsman, but she is not there. On his way home he is filled with a piercing anguish. But the volume ends on a note of affirmation:

The next day he would be going back to Grantham, to rejoin the training centre. . . . When the time came to take over a section, he would live for the horses and mules and grooms and drivers which would be in his care. He would be part of one of the many new Companies which were going out every week, to the Battle of the Somme.

*************************

Index and Chronology to The Golden Virgin: Maps and Chronology and Index

Between 2000 and 2002 Peter Lewis, a longstanding and dedicated member of The Henry Williamson Society, researched and prepared indices of the individual books in the Chronicle of Ancient Sunlight series (the first three volumes being indexed together as 'The London Trilogy'). Originally typed by hand, copies were given only to a select few. His index to The Golden Virgin is reproduced here in a non-searchable PDF format, in two parts, with his kind permission. It forms a valuable and, indeed, unique resource.

*************************

Click on link to go to Critical reception.

*************************

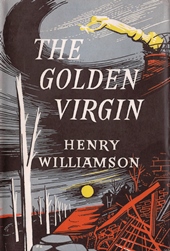

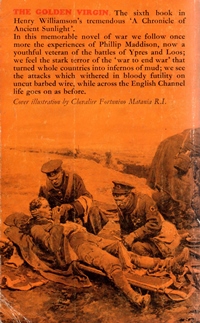

The dust wrapper of the first edition, Macdonald, 1957, designed by James Broom Lynne:

Macdonald re-issued the book at a later unknown date, using spare sheets from that edition: the year of publication on the reverse of the title page still being given as January 1966. This is clearly not the case, however, as it was published with a new, not particularly attractive, dust wrapper which bears an ISBN (International Standard Book Number). These were only introduced in the UK in 1970, so this, or soon after, is the probable date of publication. Donkey Boy was also re-issued at the same time, and given a similar jacket.

Other editions:

|

|

|

|

Panther, paperback, 1963. The edition featured this striking wrap-round contemporary drawing by Chevalier Fortunino Matania R.I. |

||

|

|

|

| Macdonald, hardback, 1984 | Sutton, paperback, 1996 |

The Macdonald cover features 'The Household Brigade Passing to the Ypres Salient', by Sir William Orpen (1878-1931); the Sutton cover is a detail from 'The Battle of the Somme', painted by Richard Caton Woodville (1856-1927).

Back to 'A Life's Work' 'Back to 'A Fox Under My Cloak' Forward to 'Love and the Loveless'