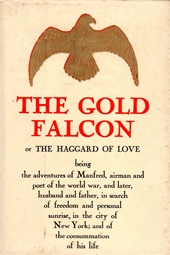

THE GOLD FALCON

or The Haggard of Love

Being the adventures of Manfred, airman and poet of the World War, and later, husband and father, in search of freedom and personal sunrise, in the city of New York, and of the consummation of his life

Published anonymously

|

|

| First trade edition, Faber, 1933 |

Publishing history and book covers

Press clippings about HW's 1930/31 visit to the USA

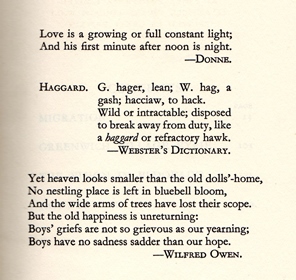

There is no dedication as such: instead the book is fronted with three quotations:

The point of these quotations do not affect the enjoyment of the book as a story to read in any way, but they are doubtless of interest to those who want to unravel the puzzle they create, which helps to reveal HW’s own purpose within the book.

The first is by John Donne (1572-1631), ‘metaphysical poet and divine’. Donne had a somewhat turbulent life but an interesting one. He travelled abroad, took part in the battle of Cadiz in1596, sailed to the Azores, was secretary to Sir Thomas Egerton, Lord Keeper of the Great Seal (and so involved in legal matters), and briefly became an MP; but mainly his mind was concerned with the problems of religious thought. He had a continuous struggle of the spirit to overcome doubt and achieve faith. (As much of the content of The Gold Falcon is covertly in the same vein then this becomes very pertinent.)

In 1601 he secretly married Ann Moore, niece of his employer Sir Thomas Egerton, then aged seventeen and still a minor, whom he had first met when she was only fourteen. He was immediately dismissed from employment and so began an impecunious married life. HW would of course have empathised with such a predicament.

Eventually, after much mental resistance, Donne took Holy Orders in 1615, and was appointed a Royal chaplain by King James I and the following year Reader in Divinity at Lincoln’s Inn. Life was now secure. But in 1617 Ann died in giving birth to a still-born child (their twelfth). Donne was grief-stricken. (Again you can see the connection to HW’s own plot in The Gold Falcon.) Donne was later made Dean of St Paul’s.

Donne was an important literary mentor for HW, whose influence in his early career was probably deeper than has been evident.

Here, the lines quoted are from ‘A Lecture in the Shadow’ from Songs and Sonnets, which is thought to belong to the pre-marriage 1590s. Donne’s verse is often about the passions of love, but much of his poetry is on the subject of death – for example, the well-known ‘Death be not proud’ from Holy Sonnets, no. 6 (1609).

These themes of love, religion and death are pre-eminent throughout HW’s own writings, and particularly here in The Gold Falcon.

The lines quoted infer that the content of The Gold Falcon is about the complexity and inconstancy of love which can only end (in death): this is indeed a theme which is inherent throughout HW’s story. Note that Manfred’s wife is also named Ann and dies in childbirth at the end of the book, so reinforcing this resonance.

The second quotation – the definition of the word ‘Haggard’, taken from his dictionary – serves two purposes. It explains a difficult and unfamiliar term which has two meanings: the look that results from extreme stress, and its particular reference within falconry to a bird caught when already adult and thus very difficult to train. Apply that to the sub-title ‘Haggard of Love’ and the concept of the Donne quotation is reinforced.

The Wilfred Owen quotation is the second stanza from a lesser known sonnet ‘Happiness’, written in February 1917. The meaning of the poem is a little obscure but tells us that the unhappy yearning of a man makes the unhappy yearnings of childhood seem happiness: now a happiness lost and unreturning. And because we know Owen is a war poet, we know that the reason for this loss of innocent happiness is ‘War and the pity of War’. We know HW also feels the same – and so we are shown the main cause of Manfred’s (and indeed HW’s own) deep unhappiness of spirit.

*************************

The Gold Falcon is an extraordinary tale which caused a great furore when it was first published, for various reasons, and especially in America. Published anonymously, speculation about the author’s identity was rife, and many leading critics made claims/guesses as to whom that was. While it became an open secret quickly enough, HW did not properly acknowledge it until the 1947 revised edition.

The Gold Falcon tells the story of Manfred Fiennes-Carew-Manfred, VC, DSO, heir to his grandfather, Lord Cloudesley. Manfred, World War flying ace hero, war poet, and war-neurotic, outwardly established and successful but inwardly in turmoil, flees to America to escape from himself, his pregnant wife and family (of which at least one child has already died – depending on which edition you read), his own fame as a writer, his memories of war, and an abortive love affair with a young German girl, to seek a new life and a new love: he finds it – but is thwarted from fulfilment.

Unknown to him (although he has brief glimpses, or rather senses its presence), he is accompanied by an allegorical, mythical, mystical gold falcon which flies high above him – let us say symbolic of his soul or spirit. Such a bird is also part of the Cloudesley crest – and we gather through small hints that there is a legend that when the bird appears a death will follow.

After an adventurous visit during which he meets a large variety of characters and situations, he learns that his wife is dying in childbirth and decides to borrow an aeroplane and fly back across the Atlantic to be by her side. But mid-way across, inevitably, he force-lands in the ocean, and shortly drowns: and so is united with the mystical gold falcon and, briefly, his dead wife.

The story is based on a visit made by HW to America over the winter of 1930-31, with an almost equal mix of reality and fictional content. Its outstanding quality is the superb and detailed picture of literary New York at that moment in time. If it was a painting (and it is certainly a painting in words) it would be of immense historic value. In some ways it bears comparison with that great icon of American literature, Scott Fitzgerald’s The Great Gatsby, which had been published in 1925.

Although the actual story line follows the course of a fairly straightforward novel – and can easily be read as such – it is also what tends to be referred to as a ‘literary’ novel. It is indeed literally sprinkled with bio-pics of writers and poets and with many quotations. But the term ‘literary novel’ has more meaning than that. There is a hidden or elusive complicated undertow, which for those who want to try and unravel or find the key has an intellectual fascination, both satisfying and frustrating. The more this is explored the clearer the total picture becomes. The literary side may not appeal to everyone (and can indeed be ignored) but it adds a richness to the book, rewarding to those who persevere.

*************************

One important aspect of the book is its direct Byronic allusion: the ‘Byronic Hero’ is the epitome of Romanticism – an outcast wandering in foreign lands, gloomily absorbed in the memory of past sin and the injustices of life. Manfred was the title of Byron’s dramatic poem where the hero, to expiate some unexplained ‘sin’, becomes an exile and wanders in the savage scenery of the Alps where he eventually conjures up the Witch of the Alps and her evil spirits, who shows him the spirit of his dead sister (whose death is the cause of his guilt). She tells him he will die the next day. His resistance to the evil spirits and his repentance of a deed he did not mean to commit mean that although Manfred does indeed die, he is redeemed and does not go to Hell: love and repentance have overcome evil. This is basically the plot of The Gold Falcon.

Lord Byron (and you will note HW’s Manfred becomes a lord) himself had fled abroad as an outcast for sins committed against the mores of Society and then remained an exile (his various affaires shocked his compatriots though he did not see any problem with them!).

HW had very recently visited the Pyrenees, and so had himself seen a similar savage scenery to that of the Alps that Byron and his Manfred saw.

The Gold Falcon can be said to be a true Romantic novel – that is, written in the style and spirit of Romanticism (as opposed to the somewhat degenerate meaning of the modern ‘romantic’ novel). The capital ‘R’ carries an important gravity. Romanticism incorporated the Imagination (with a capital ‘I’) in its fullest and widest sense.

It must be particularly noted that HW casts Manfred as a poet: by which he can ally himself with poets as a higher and more sensitive form of expression. He can allow Manfred to have deeper (and yet in some ways more superficial) reactions to situations than one would possibly normally expect. Indeed, Ted Hughes, the future Poet Laureate, stated in his Memorial Service eulogy (on 1 December 1977) that:

It is not usual to consider [HW] a poet. But I believe he was one of the two or three truest poets of his generation. . . . he created a real poetic mythology . . . an imaginative vision . . . controlled at every point by imaginative laws, and it does all the work of poetry.

There is also the association with Hamlet, not only in the form of the lecture that Manfred gives: the concept is a major thread that permeates the structure of the novel. That will be discussed further within the text analysis itself. Enough to state here that the concept of Hamlet actually follows that same Romantic theme in essence: but particularly here the idea of expiation of sin, which is a basis of the Christian religion and indeed is a distillation of one of the basic tenets of philosophy.

It is obvious that there has to be a connection in HW’s own psyche between the fantast volume The Star-born and the almost fantast The Gold Falcon. He was writing these two volumes at virtually the same time. Although The Star-born had originally been written during 1922-4, at a time when he was still raw from his recent experiences of the Great War and was desperately trying to make sense of the world and the role of religion – especially the role of Christ – the re-writing and preparation of the book for publication would have brought all those original thoughts, and the turmoil they generated, to the surface once again.

The symbolism of the mystical gold falcon, which equates with his soul, following Manfred wheresoever he goes – that is, he cannot escape from the truth which does indeed lie deep within him (and thus by default suggestion, not just HW but all mankind) – must surely be directly engendered by the thoughts underlying The Star-born, which also has a symbolic ‘white bird’.

This puts both The Star-born and The Gold Falcon into a very special and interesting category within HW’s total oeuvre.

*************************

The book is in four parts, or thinking in terms of a play (as the influence of Hamlet is so pervasive; and Byron’s Manfred is also divided into Acts and Scenes), four acts:

Migration

Greenwich Village Eyrie

The Vision in Eldorado

Homecoming

Within these the many very short chapters are also more like scenes in a play, with characters coming and going and dialogue cross-referencing. As it is of interest to know whom the literary characters are I have made a list of most of them, placed here for reference.

Part I: ‘Migration’

The book opens by setting the scene. We are introduced to Manfred and his situation: his war record, his writing achievements, his marriage (and its problems), his children (one of whom has died), his total disillusion with life, his abortive affaire with a young German girl and his subsequent decision to leave his pregnant wife for America.

He arrived in New York during the late heat of the early Fall, accompanied, unknown to him, by a falcon of rare colouring: white of breast and underwing; and a back also of a lovely whiteness, while the crown of its head was yellow, glimmering strangely like gold in some lights, particularly of the early morning.

This bird is of course the mystical and mythical ‘gold falcon’, which accompanies Manfred, flickering on the edge of his sight (actually and symbolically). We learn later that it is connected to the Cloudesley family crest – and that there is a legend that when it is seen it portends the death of the heir.

Those who know their birds will think the description of this bird does not fit a peregrine falcon. That is indeed correct for the normal form: falco peregrinus. But there is a sub-species, a pale form – falco peregrinus peregrinoides – which has golden feathers round the side and back of the neck and is normally found in North Africa, but which is known to have been once prevalent and famous for holding territory on Lundy Island – a short distance off the coast of North Devon and visible from HW’s abode at Ox’s Cross.

Further, according to a wonderful facsimile reprint of a very early ‘hawking’ book in HW’s archive (Hawking, Richard Blome, 1686, facsimile reprint 1929), the ordinary tiercel (male) peregrine anyway becomes ‘blewer’ and paler as it gets older, while a falcon taken (from the wild) after Lent is properly called a ‘haggard’ (HW’s sub-title); when ‘mewed’ (moulted feathers) the male is known as a ‘Haggard Tassel’ (viz. Romeo and Juliet which connects elsewhere – see in due course), and the older paler male becomes a ‘white tassel’.

HW’s mythical bird is therefore firmly based on fact. This falcon and its symbolic status is the pivot of the story.

Before Manfred sails we share the scene and conversation that took place in his club that last evening – the ‘Barbarian Club’ (a very thinly disguised real-life Savage Club, HW’s London club), where we are introduced to characters who are just as thinly disguised. The friend not elected to the club is S. P. B. Mais (a long-term friend, see HWSJ 49, September 2013, Robert Walker ‘S.P.B. Mais’, pp. 35-53); ‘Channerson’ is the well-known artist C. R. W. Nevinson (to whom HW’s The Wet Flanders Plain is dedicated, in tribute for the gift of an etching of a preliminary drawing for the artist’s ‘A Group of Soldiers’ – one of whom looks extraordinarily like HW). The conversation and Manfred’s thoughts are a little tetchy. (Nevinson was to take great exception to his own description.) The David Torrence mentioned is none other than D. H. Lawrence.

Once on board Manfred is reading ‘Sherston Savage’s Memoirs of a Company Officer’ (Siegfried Sassoon’s Memoirs of an Infantry Officer, 1930) which leads him to think about other war books. That this has significance for the lecture he gives while in America will be seen in due course. But his mind continuously returns to Marlene (and that should surely be pronounced in the German way – ‘Marlayna’): what she has said and done, and her reactions to what he had said and done.

Marlene was seventeen years old when he first knew her. . . . [Her] face like the rising sun, broad and strong, always laughing, her hair of Saxon fairness cut short like a page-boy’s of the fifteenth century, streaming back from her brow like sunrise, a Blakian figure of joy. . . .

[Barbara Krebs was actually older than that – and was not a blonde!]

A particular memory he has is of reading Wilfred Owen’s poem 'Strange Meeting' to her from a book with Owen’s photograph as a frontispiece. This refers to the slim volume put together by Siegfried Sassoon soon after Owen’s tragic death right at the end of the war: a precious volume given to HW by his mother. Owen’s poetry was for HW sacrosanct.

On arrival in America Manfred is met by Charles, Homer’s son. (This was Elliott Macrae, who signed himself ‘Jimmie’, who did indeed meet HW off the boat when he first arrived; but note that HW is ignoring here their initial fishing trip to Mastigouche in Canada.) Charles is newly engaged to Barbara.

Manfred is amazed by all he sees in New York – the orderly pattern of the streets, Fifth Avenue, the noise and speed of traffic, the debris of chewing-gum stuck to the sidewalks (little known in the UK in 1930!) etc. – but above all by the Empire State Building, ‘quarter of a mile high and cost half a million dollars’. Still impressive today, it must have been an amazing sight in 1930.

He is invited to dinner with Homer (of ‘World Books’ – i.e. John Macrae of Dutton Publishing). Homer has a good supply of liquor (this in Prohibition America – indeed alcohol seems available everywhere!), is seemingly bumblingly gentle and repeats his sentences twice over. Manfred pours out in lengthy earnest detail the tale of his love for Marlene. (As Macrae had met Barbara Krebs, then no doubt HW did relate the debacle of this love affair.) Homer tries to divert him several times and eventually asks about the ring Manfred is wearing.

'It’s a falcon with spread wings flying into the rising sun . . . The original Manfred crest . . .'

But he can’t quite bring himself to mention the legend (that to see the falcon means death).

|

|

HW and John Macrae on their fishing trip to Mastigouche, Quebec Province |

This long and detailed tale of his love for Marlene explains to the reader Manfred’s state of mind and deeply depressed unhappiness, but it does rather hold up the main thrust of the book. A tiny detail that emerges that has significance at the end of the book is that Manfred’s elderly black greyhound ‘Demon’ has been taken to the vet and put down before he had left for America. Also mentioned at this stage is his one-time batman ‘Corney’, who works as general handyman but is a drinker (and regular readers will recognise the gentleman, who appears in various other writings of HW), who again appears at the end.

But Homer has a secret which he doesn’t tell Manfred: Marlene is actually working for his publishing company, translating German books. It is difficult to see why HW added this into the structure – there is no evidence that it was actually true in real life and it doesn’t really bring anything to the story. One feels it would have been better to have left Marlene in the past. The only benefit is that it shows he no longer cares for her, but that is established by other means anyway – therefore that he is somewhat fickle in his love affairs: a short-lived intensity burning out to nothing.

Charles and Barbara return from an evening out bringing other friends with them, including a very unhappy girl called ‘Pinkie’, who reveals she is lesbian and whose lover Louise has committed suicide. We also meet ‘Elizabeth’, a lawyer. Both characters are based on real people and so no doubt the roles attributed to them also. Pinkie, woven in and out of the story with her sad tale, epitomises the brittle emptiness of life in New York; Elizabeth (more hazily drawn), perhaps the possibilities for a woman in this brave new world.

The group go off to a night-club. There is a nod to Scott Fitzgerald here as the sign of the nightclub has resonance to The Great Gatsby: ‘a great crescent moon with the flickering words MOON DANCING’. At the club there is a very popular singer, Jack Starlight – who was actually the well-known Rudy Vallée. Starlight has quite a major part in the book although not of any structural significance. HW obviously admired his style of singing, but there is no evidence that he was actually friendly with the singer. It does of course add considerable ‘local colour’ to the tale.

|

|

Rudy Vallée, singer, bandleader and entertainer, who has been called one of the first modern pop stars |

Part II: ‘Greenwich Village Eyrie’

The second part is fronted in the 1947 version (and more appropriately) with the Wilfred Owen quotation that appeared at the beginning of the original edition.

There is a splendid description of the apartment Manfred has rented – exactly of course as the one HW himself rented. A recent reconnaissance visit by members of the HWS established it is still there (see HWSJ 45, September 2009, Walker Burns, ‘Grove Street Blues’, pp. 33-54, which details how he tracked it down).

The apartment had three rooms, with a kitchen and bathroom; white paint and pale yellow walls glowing like daffodil in the sun shining over New York. . . . The main room, which gave the recommended view of the metallic processions up and down Seventh Avenue, and woeful smoky sunsets over the crags of Wall Street far downtown, faced north, east and west, owing to the number of tall windows which made the most of its wall-space. It was in shape, the three quarter segment of a circle. It was like being at the top of a lighthouse.

This apartment now forms the backcloth for the rest of the novel and his feelings about it reflect the particular mood Manfred is in at any time, so that it takes on a persona far beyond that of its physical existence. But Manfred is already homesick for Cornwall and his wife (he has by now been living there alone for eight weeks). However, he recollects his wedding night when, with total insensitivity, he had forced himself upon his very innocent bride. Our own emotional reaction to this novel also see-saws from sympathy to antipathy and back again: up and down like a boat on the sea.

Always he was alone, alone at school . . . alone in the Army . . . alone in the old World, alone in the New World. The trouble was that although he had crossed the sea he had brought the same old parcel of bones and skin and wornout rubbish which was himself.

Soon after he relives an aerial combat with Manfred von Richthofen (the great German air ace known as the Red Baron), whom his men had called his ‘Hun cousin’, and brings in Micky Mannock, ‘the greatest British pilot of the War’. But these exploits of Manfred are imagined – there was no such real-life role for HW – though perhaps he would have liked there to have been. He was at this time in touch with his friend from school days, Victor Yeates, who had indeed been a scout pilot in the First World War, flying Sopwith Camels – but these exploits cannot be attributed to him, although HW’s idea of having a pilot as his hero might have its genesis there.

At the time of my original investigation into this title for an HWS study day, Dr Mike Maloney suggested that the exploits of Manfred were comparable with those of the Canadian pilot William (Billie) Barker, VC, DSO & bar, MC & 2 bars, who had died when he crashed his plane on 12 March 1930. His funeral procession in Toronto was huge. HW may well have known about this, as his visit to Canada was very soon after that event. There is certainly a comparable similarity.

However, HW pasted in the front of the copy of the limited edition that has his wife’s dedication a newspaper picture. This is of Captain Lanoe George Hawker, VC, DSO (Royal Engineers & RFC), the first ‘ace’ of the Royal Flying Corps, whose exploits were exceptional. Hawker was killed in a dog-fight with Leutnant Manfred von Richthofen on 23 November 1916. The picture looks amazingly like HW himself:

Manfred’s musings are interrupted by a telephone call from Mrs Dawlish Kelt, who invites him to give a lecture to her literary ladies luncheon club. This lady was actually Miss Emma P. Mills, whose role was as in the novel. But her fictional name is clearly derived from that of Mrs Dawson Scott, the lady who had founded the Tomorrow Club (by then the international P.E.N.). HW obviously thought they were two of a kind!

Before this Literary Morning takes place there is a quite hilarious passage about Manfred’s sally into a speakeasy – the Whoopee Club. We have been told that Greenwich Village ‘was luminous with the sight of many night clubs.’ He gets inveigled into entering this one by a tout, and once inside finds himself trapped into buying expensive cocktails seemingly laced with cocaine. However, though quite scared, he manages to browbeat them and escapes.

The tale HW told his family (and no doubt all and sundry!) is even funnier, although one doubts if it is actually true. He states that he actually told the head ‘mafia’ man: ‘Don’t you know who I am?’ Beating his chest: – ‘I am Tarka the Rotter.’ They presumed this meant he was some big ‘mafia’ type boss from outside their community and became crawlingly subservient! This couldn’t be put into his anonymous novel of course: it would have given the game away; but it greatly amused his children.

The Literary Morning arrives: Manfred gets into a bit of a stew travelling there, and we are told details of the presentation of the ‘Blackthornden Prize to Sherston Savage for The Lame Huntsman – and how nervous ‘Waggoner’ had been. HW had indeed attended the presentation of the Hawthornden Prize to Siegfried Sassoon the previous year and these details are all correct – he had scribbled copious (almost unreadable) notes into his diary during the event: ‘Waggoner’ here being Edmund Blunden. (Sassoon had refused to attend the event.)

So we are given the gist of the all-important ‘Hamlet and Modern Life’ lecture. It is done very adroitly with various asides to break it up, including the fact that Barbara Faithfull is in the audience and he shows that he is falling in love with her. But the lecture is deadly serious:

'In Europe today . . . there are thousands, probably millions of young men with grey hair. Hamlet was a young man with grey hair.'

That is a very striking metaphor to cover the horrors of war-strife that the young had suffered: young still – but with the grey hair of old age. (Hamlet, you will recollect, was a soldier of some renown before the play opens.)

'For the truth as I see it, is that everyone of us who took part in the War helped to make the World War. With our deeds, with our thoughts, with our imaginative pictures of our own superiorities – the War Guilt lies with every one of us.

Therefore if we want a world free of war, and other human misery, we must change, every one of us.'

The main thrust of Manfred’s (HW’s) argument equates Hamlet with the First World War.

'The ghost of Hamlet’s father . . . has multiplied itself into the ghost of ten million men slain on the battlefields of Europe in my generation.'

Those ghosts are urging those that survived to do something to save the future: an original and striking concept. Here in the ‘play within the play’ we are back in the nutshell of the First World War. It is not usual to categorise The Gold Falcon as a war novel, but it is indeed within that category in many ways, perhaps in every way. The whole book hinges around the war: Manfred’s problems are due to his experiences of the war, his background is of the war – and HW equates what is considered the greatest play in the English language to be comparable as a metaphor for that war.

'Hamlet is Everyman. Everyman frustrated, the truth in him sent into the wilderness: the poet in Everyman denied by the barren part of Everyman.'

A bit further on in the story, when Manfred is in his own apartment and writing a passage in his own book about hunting, he asks himself:

'. . . what had it got to do with the Great War? Everything had to do with the Great War. . . .'

thus reinforcing this theory (and incidentally offering further evidence that Tarka the Otter should be considered an allegory for the war).

During this lecture Manfred has produced and tends to ‘play’ with the bottle which he brought into the country when he first arrived – which he tells them contains:

'Exhausted air. A symbol . . . stale air a symbol of the world-tired air I have been breathing. The disillusioned War generation . . . the Lost Generation.'

In the 1947 edition he puts this more adroitly: ‘I came to get new wine in my old bottle.’

But right at the end of his talk he produces a bottle from his pocket which appears to be full of whiskey: his audience is the cream of staid correct society ladies and this is Prohibition America: he proceeds to drink from this bottle and empties it, to the gasped consternation of his audience – but then tells them to relieved laughter that it was only cold china tea with lemon – so refreshing!

Manfred has been very aware of the ‘glowing’ presence of Barbara Faithfull in the audience and as he sits down at the end he is thinking:

I love Barbara, I love Barbara, I love Barbara. But I must never reveal it, never, never, never.

The thrice repetition is reminiscent of the thrice-crowing cock and subsequent betrayal of the Bible.

Later, after the luncheon and readings by nine separate poets (and yes, that actually happened), Manfred decides to visit Homer’s office, but is headed off by Homer (who appears uneasy – he is actually nervous about Marlene being seen by Manfred), who tells Barbara to take him up to the Observation Tower on the 78th storey.

Manfred and Barbara looked at each other in the sunlit tower, smiling, smiling, smiling. It was unreal and dreamlike in the height of the sky. Far, far above human sight, a white bird was soaring.

Part III: ‘The Vision in Eldorado’

(This name of the mythical Golden City was actually the telephone code for the area – giving HW an apposite title here!)

In the 1947 version this part is now headed by the Donne quotation that was on the original ‘dedication’ page – again now more appropriately placed.

We find Manfred, Homer, Charles, Barbara and Elizabeth on a train to New England, along with ‘them Yales’ (men from Yale University) who get off at New Haven. A little nod from HW to his own visit to Dartmouth made in the New Year – but which does not come into this novel. Manfred is amused to see all the English names of the towns. They are on their way to stay with Barbara’s parents, who live on Rhode Island – and Manfred makes the connection with the hens (Rhode Island Reds) his son keeps at home.

He finds the household, although very hospitable, rather hedged about with a stiff formality and somewhat rigid routine. This is setting the background ready for the eventual denouement. HW did indeed spend a weekend at Providence, Rhode Island, New England in early November 1930 at the home of a Stafford Wheeler (not Barbara’s parents), which he greatly enjoyed.

Charles keeps an aeroplane here, ‘a blue and silver monoplane’ (a Lockheed Altair), named ‘The Spirit of World Books, Incorporated’. Charles had wanted to call the plane ‘The Spirit of New England’: this is very obvious reference to Charles Lindbergh’s plane ‘The Spirit of St Louis’, with which he had crossed the Atlantic in 1927.

Manfred’s feelings for Barbara continue to grow, but she keeps him at arm’s length. They go skiing but Manfred, being too daring, hurts his ankle. At the end of the weekend the two men fly back to New York – a nervous Manfred glad that his hurt ankle means he could not take the controls. As they leave he learns that the wedding between Charles and Barbara is to take place the following month in New England and he is asked by Mr Faithfull to be best man.

Back in his apartment and writing his book, he is telephoned by Mrs Dawlish Kelt offering him the use of a box at the Opera house to see Wagner’s Walküre. Manfred phones Charles but he is going hunting; then Pinky, but she has a previous engagement; and so ends up inviting Barbara. He prepares a dinner for her in his apartment (every detail given!). All goes well and the chapter ends with the words: 'smiling, smiling, smiling.' (Again that thrice repetition.)

HW noted in a letter to his wife dated 30 November 1930 that he had been to the Opera to see Valkyrie with ‘Miss Barbara Sincere, a secretary at Duttons’. He had bought himself a book of cheap tickets for the season for Monday nights.

Afterwards she takes him back to her own apartment for ‘cawfee’. She tells him she is not sure that she will actually marry Charles: and then reveals that apart from Elizabeth, the other flatmate is Marlene, who now means nothing to Manfred.

We learn here that the newspapers are reporting that:

A great dancer had died two days before in Europe . . . a ballet of a hundred dancers danced her swan-song.

No name is given, but this was the great dancer Anna Pavlova, who died on 23 January 1931: her most famous role was that of ‘The Dying Swan’ – so a neat play on words. He also marks here the death of novelist Arnold Bennett (which actually occurred just after HW's return to England).

Manfred wanders around New York looking at the poverty of this great city. Then he goes to see Barbara, but Charles arrives briefly. Sensing an atmosphere Manfred leaves with Charles and they go on to see Pinky. Manfred takes her out, but later returns to Barbara, who tells him she is not going to marry Charles and is going to leave World Books.

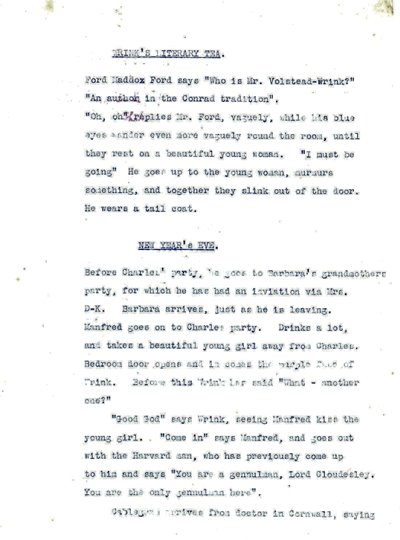

The scene and tone changes momentarily. We learn that the books of Commander Thomas Volstead-Wrink are also published by Homer, and that he is to visit New York where he will be given a great publicity relations ‘Literary Tea’. Wrink is based on Thomas Washington Metcalf, a writer who lived near HW in Devon. Metcalfe, or ‘Mecca’ as he was called, was to take great exception to his portrait in this book (see HWSJ 45, September 2009, pp. 29-30, Anne Williamson, ‘Thomas Washington Metcalfe’). There is no evidence that Metcalfe did visit America while HW was there, and the ‘Literary Tea’ referred to was actually given for HW himself. He had a great deal more publicity than he allows Manfred!

|

| From the New York Herald Tribune |

|

| HW's notes for Wrink's Literary Tea |

Manfred and Barbara now admit their love for each other and she tells him she will ‘never forsake him, never, never.’

Now truly the Great War was over, and the ghosts of the ten million men were at peace; and Hamlet had broken from the prison of himself.

He learns that his grandfather, Lord Cloudesley, is very ill (he is heir to the title, his father having been killed in the war), and indeed he dies soon after. He also learns from Homer that Wrink has suggested Manfred should return home, as his wife is having a difficult pregnancy. Homer also tells him that Barbara and Charles have had a ‘tiff’ but that all will be well if no-one interferes. Manfred understands the hint.

Sending a cable to his wife, she reassures him by return that all is well, and he must stay until his planned return in the spring. He goes back to Barbara, where he realises ‘that at last he was loved as he had dreamed'.

A cable arrives from Ann saying she is fine, and that he is to stay and ‘be happy’. Manfred and Barbara are happy together. Manfred feels

his life rise strong and balanced in his eyes. . . . And with his book finished: the book which for years had been as Dosmare, he Tregeagle condemned to unrest until he had emptied the dark tarn with a broken limpet shell, or to twist sand into ropes.

This extremely enigmatic sentence refers to an ancient Cornish legend about Dosmare (or Dosmery) Tarn (pond) on Bodmin Moor in Cornwall, which the spirit or ghost of local rent collector Tregeagle was condemned to empty with a broken limpet shell and/or to twist sand into ropes, through no real fault of his own. (He had been summoned back from the dead to prove a legal point and was then such a nuisance that the parson could only control him by this punishment.) It has no point in The Gold Falcon – other than that HW is laying down ‘local colour’, showing Manfred is Cornish!

But now word goes round the rigidly puritanical social circle. Mrs Dawlish Kelt telephones to offer opera tickets again but warns him against taking Barbara – as people will talk and her reputation will be ruined, he being a married man.

On the phone Barbara is distant: she has to meet her father off the train at Grand Central Station, and may have to return home with him. Manfred realises Mr Faithfull is putting his foot down. This scene ends with Manfred saying to himself:

'But thou wouldst not think how ill all’s here about my heart.'

These words are spoken by Hamlet to Horatio just before his fight with Laërtes. Manfred, like Hamlet, senses impending doom.

Frank Faithfull telephones to say Barbara will not be coming to the opera and puts the phone down. Then a letter arrives from Barbara by special messenger, ending their relationship because of her parents’ distress and utter disapproval, and:

'. . . whatever we like to think about the situation, it isn’t square and beautiful and shining. Four thousand miles of sea water make Cornwall amazingly remote but it’s there all the same.' [i.e. Manfred’s wife is waiting there.]

This is a very noble letter – and is indeed one actually written word for word by Barbara Sincere to HW (and which she was startled to read in the typescript of the book).

For Manfred: ‘Time was empty and grey and blind as space.’

(Within the concept of the Hamlet theme, Barbara’s betrayal can be seen as equivalent to that of Ophelia of Hamlet. But he does not kill off his female character here as was his wont with recalcitrant lovers. Instead it is both Manfred and his wife who die.)

Manfred now attends Wrink’s ‘Literary Tea’ in honour of his book ‘Landfall off Vallombrosa’ (actually Metcalfe’s book One Night in Santa Anna, Macmillan (not Dutton), USA 1931). Also there we find P. D. Bradford (J. B. Priestley – but this is changed to Hugh Walpole in the 1947 edition); Mark Cradocks Speuffer ‘the friend of Conrad’ (a thin disguise for Ford Madox Hueffer, better known as Ford Madox Ford (1873-1939) of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, and quite a prolific writer and critic, best known today for his war tetralogy Parades End); and the Professor he met on the boat out. Also present are Alick Peace (Alec Waugh, friend of HW, which his brother Evelyn certainly was not! ‘The Bloom of Adolescence’ is Alec Waugh’s book The Loom of Youth) – and inevitably, Barbara, Elizabeth, and Marlene.

Manfred says of P. B. Bradford that he writes ‘boloney out of Dickens, nice big boloney, chunks not slices'. Priestley was to get his own back in an acidic review in due course!

Elizabeth puts him straight about Barbara and her parents. Then he sees Hélène – last seen on the boat travelling to the US, who informs him she lives exactly opposite him. After a while Manfred slips away to join Barbara outside. They go to a drugstore and drink hot chocolate. (Richard Snow, mentioned here, is very obviously the well-known American poet Robert Frost.) Barbara is adamant that her decision stands, and despite a further meeting after her father has gone back home, she does not waver.

Manfred returns to his apartment in frenzy. He quotes Wilfred Owen and cries out:

'O poet, shall man ever break the terrible, terrible, terrible spirit in people which arose in 1914-1918?'

(That HW attributes every ill solely to the First World War seems a little narrow-sighted – but it fits his portrait of Manfred.)

Manfred writes a letter to Barbara (as HW did in real life), and then in true Shakespearean mode there is a scene of comic relief in which he is set upon by a truculent cab-driver, who in turn is set upon by another: while our hero slips away leaving them to it.

There follows a quiet scene when Homer gives a lunch for Manfred and Marlene. While Homer takes a nap, Marlene reads William Blake’s Marriage of Heaven and Hell. William Blake, arch Romantic though not of the actual Romantic coterie, was one of HW’s great influences. This long poem discusses the predicament that humanity finds itself in, from religious thought to human relationships, and is worth considerable thought within HW’s mention of it here. It is part of HW’s intention that The Gold Falcon is a morality play in prose. Manfred states of the Blakeian poem (rather obscurely): ‘organized religion is nailed down in a hundred words or so. It is a corollary of "Hamlet".’ (For further discussion of this point, see AW, ‘The Gold Falcon: A Morality Play in Prose?’, HWSJ 45, September 2009, pp. 14-5.)

Part IV: Homecoming

In the 1947 version this is moved from the 1933 chapter 57 to chapter 63, where there is a quotation from Psalm CXXXIV (134):

If I take the wings of the morning, and dwell in the uttermost parts of the sea; Even there shall Thy hand lead me, and Thy right hand shall hold me.

There is also a quotation from Ronsard: Car l’Amour et la Mort n’est qu’une mesme chose. ('Love and death are only one and the same thing.')

It is New Year’s Eve and Manfred is at the Opera lying up in the gallery (as we know HW used to do in the Covent Garden Opera House in the early 1920s). Down below in the box he sees Wrink, being very ‘English’. Manfred is hoping that Barbara will join him. He had finished his book that day. Deciding Barbara is not coming he leaves, but as he reaches the street so she arrives – though only to give him an urgent message that he contact Charles.

He arrives at the New Year’s Eve party being given by Homer and Charles. Homer is not there and Charles is evasive, saying they must wait for him to explain the cable that has arrived earlier. Manfred realises this has to be bad news and he is filled with dread, but is trying to hide this. Wrink is also at this party and they have their usual slightly contentious conversation.

A girl interrupts them and tells Manfred that Marlene has said:

'Only you could write the book everyone is waiting for. Are you going to write it?'

Manfred replies ‘How could anyone write it?’ Then he quotes from

a poor farmer’s son, a lonely, friendless little boy who has been dead nearly fifty years and is still unappreciated in England. It is one of the last things he wrote, as he lay dying, about my age, of anguish and intestinal tuberculosis: ‘To be beautiful and to be calm, without mental fear, is the ideal of nature.’

(The writer is his great mentor, Richard Jefferies.) Homer returns. He takes Manfred aside and tells him the cable stated that his wife is very ill from childbirth and the baby is dead. Homer thinks Manfred can return to England by the regular boat, but Manfred has already thought out that this will take too long and that he must fly back if Charles will let him have his aeroplane (as an ex-pilot he has the skill, even if not recently exercised).

Although reluctant due to the fragility of the plane for such a venture, Charles and Homer agree: a plan of action is decided and preparations are made for this perilous flight.

Manfred sends off a cable: ‘I will see you at sunrise.’ He arranges for the Shenandoah Cafe, where he has made friends with Yewdale the owner, to prepare flasks of ‘cawfee’ and sandwiches, and a send-off party rendezvous there, arriving with police siren escort: Charles, Homer, Wrink, and Jack Starlight. Yewdale wants to join them. (This was actually the name of a well-known editor at Dutton, who was extremely upset by this use of his name.)

At the airport a publicity send-off has been organised: Starlight knows exactly what to say to make greatest effect, while Wrink jumps in on the act for his own publicity purposes. (Manfred’s ‘Goodbye’ to World Books staff is synonymous with HW’s goodbye to Dutton Publishing!) This is a ‘film-set’ scene. (Possibly HW was thinking in terms of a possible film for this book – and that this was a nudge!)

Everyone is very nervous about the take-off with the extra heavy fuel load, but all goes well.

The flying details are all absolutely correct: HW consulted his wife’s cousin, the record-breaking pilot Francis Chichester (later to achieve equally great renown in the 1960s for his single-handed sailing exploits), and made copious notes (see Henry Williamson and Francis Chichester).

The flight details – route, scene beneath, weather – are all woven with Manfred’s thoughts, and make for subdued dramatic reading.

It was terrible to be alone in the unknown darkness.

There is fog and a storm, then he flies on in a clear sky; time and space are suspended with all fatigue, all desire, all grief. Then he sees below him the ship Empress of India and thinks his course must be wrong, and alters his course in her wake.

In jubilation he flies only a few feet above the water, but suddenly the engine noise and speed increase and do not respond to his manipulations of the controls: the engine dies and he ditches in the sea.

When the sun rose on the placid Atlantic an hour later its beams touched the little blue and silver monoplane lying in the water, lifting with the slow ocean swell.

So Manfred waits for death to overtake him. His thoughts are calm as he considers his position. He writes a letter to his son Hugh with the message:

Fight neither in deed nor in thought, be calm within thyself, act only to balance mind with body, see thyself as the sun to the flesh. In hope and trust of the sun I bid you farewell . . . and in farewell I do but greet you, in the laughter of the sun, the servant of the Father of Man beyond time and space.

This letter is very Shakespearian in concept: ‘To thine own self be true, And it must follow, as the night the day, Thou canst not then be false to any man.' This is said by Polonius to Laërtes – so following HW’s ‘Hamlet’ theme for the book.

The letter is sealed in that special bottle he had found on the beach in Cornwall before he left, and thrown into the sea. That it did reach his son is discovered many years later in the last volume of HW’s major work A Chronicle of Ancient Sunlight, in which Hugh Cloudesley features.

The plane starts slowly to sink and he realises death is near, but he sees a light on the horizon and thinking it is a ship with some difficulty, and ingenuity, lights a flare; but it drifts into the plane and sets its canvas fabric fuselage alight; he has to jump into the water in order to swim towards the light and rescue.

He then realises that the light is actually the morning star (usually a symbol of hope – and for HW also associated with the 1914 Christmas Truce). Dawn has risen. There will be no rescue. But as he drowns he has consolation:

. . . as the black cold of the water struck . . . he saw the flash of wings in the flames, and a bird was flying round above him, watching him, beating its wings with nervous flickers, to glide swiftly to the fire, and return to him again. It flew through the flames, crying shrilly, but always returning and he saw . . . that it was white, and its head glimmering like gold, and it was his falcon, which came to him and was of him when with his last strength he held out his arms.

The scene changes in the ultimate chapter, back to Manfred’s bedroom in his own home. Ann is already dead but is still present. In the kitchen are the two elderly servants, man and woman, each grieving aloud with their own images: he (Corney) of his master and senior officer, remembering the war years and singing a war song as he drinks from bottle, ‘It’s all in Tolstoy’; so referencing that ‘War and Peace’ concept that haunted HW (the 1947 version is quite different here, referring to the Second World War, which completely detracts from the concept); the old housekeeper of her mistress and her lonely death. This scene is very similar (surely deliberately) to that which opens the first book that HW wrote, The Beautiful Years.

The black greyhound (the dog which had been put down before Manfred left for America) is there, staring at the wall, then is outside running round and round ‘something’ in circles. The ‘something’ is Manfred, who then emanates in the bedroom where Ann is waiting for him. He says: ‘Love is more cruel than death.’ (Hence the 1947 edition Ronsard quotation: ‘Love and death are only one and the same thing.’)

It is a very well-structured and managed scene, not overstated. HW was extremely good at presenting ghost stories, and there are a small handful of gems within his work which tend to be totally overlooked.

Manfred is cold, wet, and confused and has not realised what has happened until he realises he has no shadow. He also realises that Ann will not be with him: she will stay there with her children, who are all together: both the dead and the living.

He stood by the window, “It is sunrise and I have come to you. Now I must go, even as you must remain. Every man is alone. Is there no other Truth at the end, O sun?”

So saying, he looked straight at the sun; the light and the fire of the sun pouring into him through his unflinching eyes; and he felt the new strength and growth of himself. . . .

She stroked his head, smiling upon him as his head became smaller and like to gold; he was shrinking, transmuted to the shape of a falcon, and his glance was equal with the glance of the sun. The wings lifted, tremulously – lifting the falcon to the window ledge; there it turned, to see shining upon the countenance of the sleeping boy the likeness of the falcon head; and poising its wings, it arose, and flew up, and was of the sun in Heaven.

Manfred / HW is, ultimately, alone.

*************************

Publishing history and book covers

Press clippings about HW's 1930/31 visit to the USA