TARKA THE OTTER

His Joyful Water-Life and Death in the Country of the Two Rivers

With an introduction by

The Hon. Sir John Fortescue, K.C.V.O.

|

|

| 1st trade edition, Putnam, 1927 |

Dedication:

To William Henry Rogers

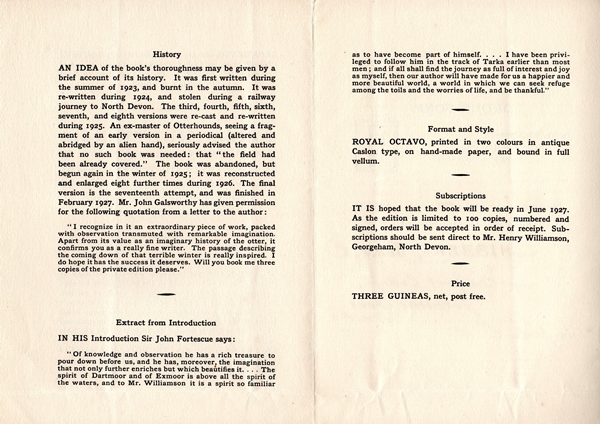

The publishing history of Tarka the Otter is extensive, and complicated with various editions and numerous reprintings, some with only small changes in the text (Hugoe Matthews’ Henry Williamson: A Bibliography devotes nineteen pages to this book). A selection of the most important is given here.

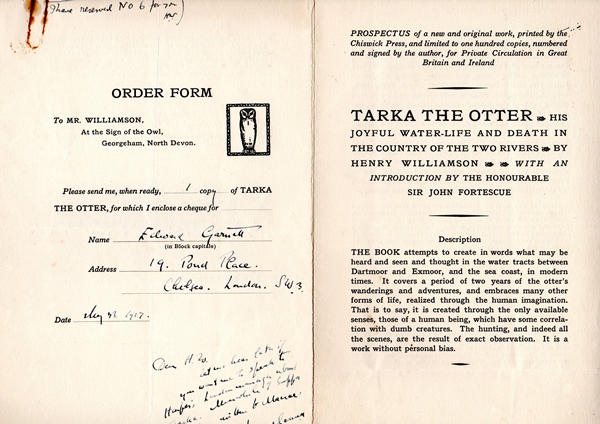

The book first appeared as a limited subscription edition of 100 copies bound in full vellum, privately published, printed by the prestigious Chiswick Press, in August 1927, price three guineas.

This was followed by a further limited edition of 1000 copies published by G.P. Putnam & Sons, also printed by Chiswick Press, bound in half brown cloth/cream buckram, October 1927, price one guinea.

First trade edition: Putnam, October 1927 (7/6d), with jacket by Hester Sainsbury

(six reprintings in 1928, a further five in 1929 – and many more in due course)

Dutton, USA, February 1928 ($2.50)

First illustrated edition by Charles F. Tunnicliffe, Putnam, 1932 (5/-); reprinted many times

Penguin Books 1937 (and subsequently Puffin, 1949 onwards – a diary entry for 14 February 1948 in Ann Thomas's handwriting records that HW, in response to a letter from the publisher, agreed that Tarka the Otter should in future be published by Puffin instead of Penguin)

Incorporated into The Henry Williamson Animal Saga, 1960

The Nonesuch Press, 1964, a new edition, illustrated by Barry Driscoll

The Bodley Head, 1965 – and a new ed. 1978, with Introduction by Richard Williamson (HW’s son) and 16 colour photographs by Steve Downer taken on location during the Rank film production.

Webb & Bower, 1985, with new Introduction by Richard Williamson, and lavishly illustrated with photographs by Simon McBride of the area and scenes in the book.

The Folio Society, incorporating most of the features of the 1932 first Tunnicliffe illustrated edition, cased, October 1995 (for which Anne Williamson wrote an Introduction, ‘Henry Williamson: Dreamer of Devon’, printed separately in trade magazine Folio, Autumn 1995, pp. 18-26).

Foreign editions abound: for example, German, French, Italian, Swedish, Czechoslovakian, Russian, & Japanese (in the last language particularly, reprinted in large numbers over several years); examples of dustwrappers are given on the Overseas editions page.

Tarka the Otter has never been out of print in the eighty-six years (as at 2013) since the original publication and is currently selling over 2000 copies every year. In an editorial for HWSJ 16 (1987 – a special edition for the 60th anniversary of the publication of Tarka), I noted that 18,000 copies had been sold in 1984 and 11,000 in 1985. The Russian edition (1979) alone was 75,000. It is impossible to put a figure on the total number of copies sold, but I would suggest it has to be at least four million.

Tarka the Otter was awarded the Hawthornden Prize for Literature in 1928 and is considered one of the great classics of English literature. It is currently available in the Penguin Modern Classics series.

In 1978 the book was recorded as an audio-book read by Sir David Attenborough.

In the early 1980s I was approached by Dr Graham Wills, on behalf of Devon County Council, asking if the HW Literary Estate would be willing for a ‘Tarka Trail’ to be set up along the route taken by Tarka in the book, to make a tourist attraction. This involved several right of way paths and defunct railway lines. We were only too happy to cooperate in such a scheme, which is now a thriving feature of the countryside of North Devon.

There is also a ‘Tarka Line’ railway running between Barnstaple and Exeter, which passes several famous ‘Tarka’ landmarks, including the well-known Junction Pool. Since then, many other enterprises have taken advantage of the use of the name for commercial purposes, some of which would probably have amused the author (and some not!).

*************************

Tarka the Otter follows the birth, ‘joyful water-life’ and inevitable death of a male otter – Tarka, the Water Wanderer – in the ‘country of the two rivers’, namely the Rivers Taw and Torridge in North Devon which share a common estuary beyond Barnstaple, and the famous Braunton Burrows (extensive sand-dunes, until recently a National Nature Reserve), but also ranging the length and breadth of Exmoor and the coast from Lynmouth and round back to Baggy Point, the brooding cliff next to the Burrows, and by following the Torridge inland, across to Cranmere Pool on Dartmoor.

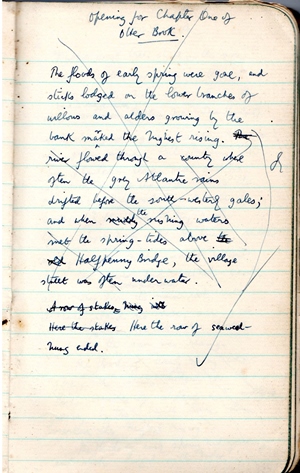

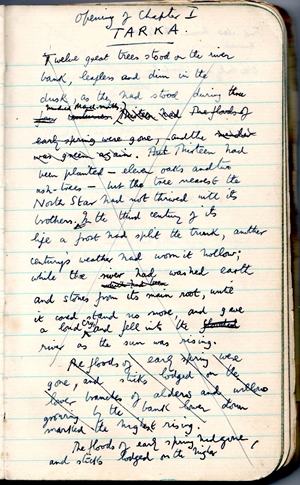

Tarka was born in ‘Owlery Holt’ (a ‘holt’ is the name given to dry holes amongst tangled tree roots in river banks that are an otter’s resting places) near Canal Bridge (actually an old aqueduct, very picturesque) on the river Torridge near Torrington (still a most magical place today). The opening of the book sets the scene:

Twilight over meadow and water, the eve-star shining above the hill, and Old Nog the heron crying kra-a-ark! as his slow wings carried him down to the estuary. A whiteness drifting above the sere reeds of the riverside, for the owl had flown from under the middle arch of the stone bridge that once had carried the canal across the river.

Below Canal Bridge, on the right bank, grew twelve great trees, with roots awash. . . .

That opening word ‘Twilight’ has been changed from the original ‘Dimmity’: both Sir John Fortescue and T. E. Lawrence thought ‘dimmity’ a little precious: but HW retained it elsewhere in the book! I have explained elsewhere that I see a big similarity about those twelve great trees to the opening of W. H. Hudson’s Far Away and Long Ago,where Hudson has twenty-five Ombu trees growing in a row (HWSJ 41, September 2005, Anne Williamson, ‘A Purple Thread’, pp. 39-49, see p. 47). Hudson, after Richard Jefferies, was one of HW’s most important influences.

We find in the opening scene many of the creatures that frequent the river and are to provide a thread running through the tapestry of the tale, for example, Old Nog, the white owl, and Halcyon the kingfisher. There had been an otter hunt that morning and we learn straight away of:

Deadlock, the great pied hound with the belving tongue, leader of the pack whose kills were notched on many hunting poles. . . . Deadlock was the truest marking hound in the country of the Two Rivers.

But the Master sees that the bitch otter that Deadlock snaps at is heavy with young and calls off the surly hound – for towards the end of the book Deadlock is described thus:

And there Deadlock, his black head scarred with old fights, sat on his haunches, apart and morose . . .

Later that night, the bitch gives birth in Owlery Holt and so Tarka and his two sisters come into the world. Her mate is around, but in due course the Hunt comes through again and a kill is made: the dog-otter that was Tarka’s father has succumbed.

Soon we meet ‘Marland Jimmy’, an old dog-otter who lives in the clay-pits of Marland Moor and is given that name by the clay-diggers, who see him frequently. Marland Jimmy is a great character – but who sadly ends his life frozen to death in Horsey Mere during the Great Winter.

We share in Tarka’s early months of growth and his wanderings, his fears and his joys, but always from the point of view of the otter, without sentimentality. It is as truthful a portrait of a wild animal that there can ever have been written.

We meet the poachers after salmon, and learn that ‘Shiner’ gets bitten by Tarka and loses a finger-tip. A small cameo here, the poachers play a larger role when HW writes Salar the Salmon in due course.

The little family group are joined by an elderly bitch-otter, Greymuzzle. The group drift down the river and come to the ‘Long Bridge’ at Bideford:

In front twenty-four arches, of different shapes and sizes, bore the long bridge. . . . which monks had built across their ford two centuries before the galleons were laid down in the shipyards below to fight the Spanish Armada. [Tarka had to] swim hard against the tide pouring between the two piers.

A new strong dog-otter appears and mates with Tarka’s mother: Tarka is chased away – his mother no longer caring about him, and so Tarka –

was alone, a young male of a ferocious and persecuted tribe whose only friends, except the Spirit that made it, were its enemies – the otter hunters. His cubhood was ended.

But Tarka meets a young small female with a white tip to her tail. ‘White-tip’ and Tarka play together, he enamoured, but an older dog-otter chases him off, biting him, and Tarka drifts down to the estuary and the Burrows (an extensive area of sand dunes which we have first met in The Pathway), where he finds Greymuzzle: and after a while these two mate.

There follows a chapter describing Baggy Point, the dark promontory dominating the skyline north of the Burrows, with all its myriad associated forms of life, where Greymuzzle prepares to have her young. We meet characters from earlier stories: Kronk the raven and Chakchek the One-eyed (‘a small dark star twinkled and swept to its orbit, twinkled and poised on its perch’) are using the air currents that sweep up the cliff-face. Kronk gives a warning. He has seen a man climbing down, jumping across the boulders still smothered by the tide. The man reaches the tiny beach and enters the cave that runs back into the cliff. This is Seal Cavern – and here the man finds a young seal. The mother is near and apprehensive. The man also sees an otter making a bed of dry grasses and seaweed. The seal is uneasy. The man takes out a whistle made from an elderberry stick and plays a few notes on it. This calms the seal, and she allows the man to touch her. The man is, of course, HW.

The finest scene in the book is possibly chapter nine, ‘The Great Winter’, where the arctic wind ‘pours like liquid glass’ over the Braunton Burrows and the Great Field, and a magnificent Greenland falcon and Bubu the Terrible, a snowy owl from the Arctic, arrive ‘in the time of ice and fog’ to hunt the few creatures still able to move.

And the sky was to the stars again – by day six black stars and one greater whitish star, hanging aloft the Burrows, flickering at their pitches; six peregrines and one Greenland falcon. A dark speck falling, the whish of the grand stoop from two thousand feet heard half a mile away; red drops on a drift of snow. By night the great stars flickered as with falcon wings, the watchful and glittering hosts of creation. The moon arose in its orbit, white and cold, awaiting through the ages the swoop of a new sun, the shock of starry talons to shatter the Icicle Spirit in a rain of fire. In the south strode Orion the Hunter, with Sirius the dog-star baying green fire at his heels. At midnight Hunter and Hound were rushing bright in a glacial wind, hunting the false star-dwarfs of burnt-out suns, who had turned back into darkness again.

There is more in that passage than just the actual description. It has allusion to HW’s book The Star-born, already written but not to be published for a few years yet, and so the passage takes on the whole ethos of that book. The cross-referencing of various threads in HW’s early work has to be taken into account in any analysis of his writing. So we find that Tarka the Otter not only has a hidden ‘war’ theme but also a theme of redemption.

Sadly, Marland Jimmy gets frozen into the ice. Driven by hunger due to the frozen land and water, Tarka and Greymuzzle, who has a puny cub, find a farm where duck are kept. But Tarka gets caught in a trap: Greymuzzle bites through his claws to free him but she is caught by the farmer and killed. Tarka escapes.

Tarka was gone in the mist and rain of the day, to hide among the reeds of the marsh pond – the sere and icicled reeds, which now could sink to their ancestral ooze and sleep, perchance to dream; . . . The south wind was breaking from the great roots the talons of the Ice Spirit . . .

The ‘First Year’ ends with a strange cameo. For one brief paragraph an ‘I’ enters the story.

And when the shining twitter ceased, I walked to the pond, and again I sought among the reeds, in vain; and to the pill I went, over the guts in the salt grey turf, to the trickling mud where the linnets were fluttering at the seeds of the glass-wort. There I spurred an otter, but the tracks were old with tides, and worm castings sat in many. Every fourth seal was marred, with two

toes set deeper in the mud, They led down

to the lap of the low water, where

the sea washed them away.

HW is referring here to his tale of the rescued otter which had lost its two claws in a trap and had then run away, to be searched for in vain. An odd mixture of fact, fiction, and myth: obviously deliberately included despite its peculiarity of the intrusion of ‘I’ into the tale.

The second part of the book ‘The Last Year’ opens on Dartmoor, with HW’s magnificent phrase:

Bogs and hummocks of the Great Kneeset were dimmed and occluded; the hill was higher than the clouds. . . .

and continues with lyrical description of the area that surrounds the famous Cranmere Tarn, or Pool. It is spring, and Tarka makes his way back down the river in joyous mood reflecting the spirit of rebirth of the season. As he travels he picks up the scent of White-tip and hears her cry. She is distressed as that morning hounds had been through and she had lost her cubs as she fled from a terrier, and her mate had been killed. White-tip stays with Tarka briefly, but then he travels on alone arriving at Junction Pool, a famous landmark on the River Taw.

The Otter Hunt with huntsmen and hounds is an ever-present menace with increasing crescendo and intensity, like a tumultuous storm getting closer and closer, from the very first rumblings of disaster early in the book when Tarka’s father is killed.

Now it is the turn of White-tip to be hunted. As she flees so she meets up with Tarka again. Then Tarka becomes the hunted animal. There follows a detailed description of the actual hounds as they work the river, with name after name, each with its own characteristic, like some roll-call to arms. They are indeed as a marching army going into battle.

Tarka hides in Spady Gut, a drain guarded by a wooden gate that controlled the flow of water. But the hounds are aware of his hiding place and the Huntsmen close in. Bite’m the terrier is sent in and gets hold of Tarka’s rudder. A Huntsman grabs the terrier and hauls it out still clamped onto Tarka’s rudder. Tarka twists and bites the Huntsman, who drops both animals: hounds close in but Tarka bites Deadlock and makes his escape into the rush of the turning tide. Bite’m is pulled with him but then lets go. Tarka, though wounded, is free. This is, of course, as a prelude to the final scene.

Recovering as he swims on down the river, Tarka eventually meets up with White-tip again.

Each was pretending not to see the other; so happy were they to be together, that they were trying to recover the keen joy of meeting.

But they are disturbed by a man with a dog out ferreting and White-tip disappears, while Tarka gets chased off. Alone, he continues on up to Exmoor, and chapter fourteen opens with another of those great sentences:

When the bees’ feet shake the bells of the heather, and the ruddy strings of the sap-stealing dodder are twined about the green spikes of the furze, it is summertime on the commons. Exmoor is the high country of the winds . . .

Dodder is a parasitic plant which spreads long thin red shoots like a giant red spider-web to enable it to cover and feed on gorse and bramble. There follows a lyrical description of the moors that HW loved so well. A branch of his forebears came from the area, and he felt this was his spiritual home. So we roam over the Chains and Pinkworthy (‘Pinkery’) Pond, Hoar Oak Hill and the East Lyn Water, meeting the creatures and plants that inhabit this wilderness. This area was also to be the setting of his last great book, The Gale of the World, volume 15 of A Chronicle of Ancient Sunlight.

As the chapter ends, Tarka finds a quiet hiding place to sleep. He awakes to the sound of yet another hunt. Deadlock is prominent in this hunt, close on to Tarka at every turn. They are both thrown down the torrent of the Glen Lyn, and although Tarka escapes he is seen and given away again by a man standing on the bridge who

took off his hat, scooped the air, and holla’d to the huntsman . . .

Tally-ho!

This is ‘Pa’ Hibbert. The melee continues until Tarka gets down to Lynmouth where he is confronted yet again by Deadlock: sinking his teeth into Deadlock’s neck, the otter pulls the hound under water. The huntsman grabs the drowning Deadlock and hauls him out of the water – Tarka lets go and escapes out into the Severn Sea – another prelude of the inevitable ending.

Tarka gradually makes his way back round the coast, passing the lime-kiln at Heddon Water, past Combe Martin Bay and on across the dreaded Morte Bay where the tide rips at Bag Leap. He lands on The Morte (another of HW’s favourite places – very like Baggy Point) to rest awhile. Then he continues onto Woolacombe Sands and going ‘up a steep bank to the incult hill, pushing among bracken, furze, and brambles, . . . he reached the top of Pickwell Down.’

Interestingly, this route was to become extremely well known to HW: once he had bought the Field at Ox’s Cross and built his Writing Hut, this was the way that he took to get up and down the cliffs to the beach at Black Rock. No doubt he was already using it at this earlier stage in his life. Indeed, as the otter continues it comes to where:

The stream flowed below a churchyard wall and by a thatched cottage, where a man, a dog, and a cat were sitting before a fire of elm brands on the open hearth. . . .

The cottage door was pulled open, the spaniel rushes out barking. A white owl lifted itself off the lopped bough of one of the churchyard elms, crying skirr-rr. . . . Striking a match the man saw, on the scour of red mud, the twy-toed seal, identical with the seal that led down to the sea after the Ice Winter.

That of course, is Skirr Cottage, situated next to the church in the village of Georgeham – and the man is HW.

Tarka continues, passing Cryde (Croyde). He is actually following the scent of White-tip, whose trail he has been following since climbing the cliff to Pickwell. He crosses the sandhills of the Burrows and returns to Horsey Marsh and on to Ram’s Horn Pond, the scene of the frozen winter earlier.

Chapter seventeen again opens with one of those set-piece phrases:

All day the wind shook the rusty reed-daggers at the sky, and the mace-heads were never still.

A short scene of human fishermen, then Tarka swims out to catch himself a fish, but Old Nog catches a salmon – many times his own weight but ‘it was a fish, and Old Nog was a fisher.’ As Tarka drifts past Old Nog he hears a whistle: ‘Hu-ee-ic!’ It is White-tip. ‘Her cry was like wet fingers drawn over a pane of glass.’ (Try that – it is exactly so!)

White-tip is with two cub otters, and the four of them work together to catch themselves a fish, but the cubs are not experienced enough. White-tip and Tarka mainly play together. On the next tide they all fish and eat well: then –

Tarka and White-tip stole away on the ebb to the sea, leaving the young otters to begin their own life.

The scene changes to Beam Weir, above Canal Bridge where Tarka had been born.

Black bits of old leaves turned and twirled in the flooded weir-pool above Canal Bridge, like the rooks turning and twirling high in the grey windy sky.

The river is in spate and the salmon are leaping. Tarka and White-tip catch a fish, found later by the water-bailiff, ‘with bites torn from behind its shoulder – the mating feast of otters.’ Thus the coupling of the two otters, so unobtrusively placed into the story.

The winter passes: the otters had moved down to the estuary again but now White-tip knows where she is going – back to the Twin-Ash Holt above Orleigh Mill, where she was born. There is a detailed description of the area, and Old Nog and Halcyon the Kingfisher are brought back into the centre of the story. Then five dark shapes are seen:

White-tip had brought her four cubs from the Twin-Ash Holt. . . . Tarquol, the eldest cub, was following White-tip, for he liked to do his own hunting; and it was in the Pool of the Six Herons that the strange big otter, who chased him in and out of the piers, never biting or sulking, was to be found. . . .

Tarquol swam near Tarka; the cub was lithe and swift as his parent . . .

At Canal Bridge they

played the old bridge game of the West Country otters, which was played before the Romans came. . . . Tarquol followed Tarka out of the river and along the otter-path across the bend, heedless of his mother’s call. [but] Tarka went on alone . . . and slept, while the water flowed, and he dreamed of a journey with Tarquol down to a strange sea, where they were never hungry, and never hunted.

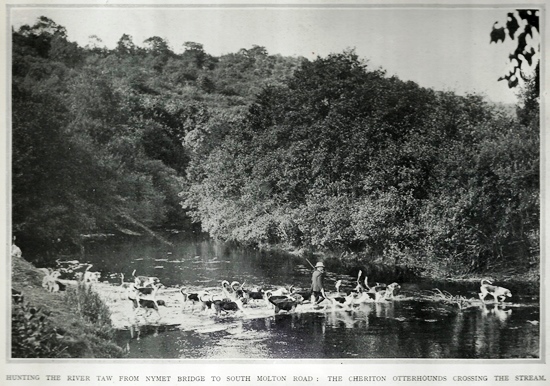

But in the real world he awakes to ‘Joint Week’, when Otter Hunts join together to go out every day for a major war on otters. In the Tunnicliffe edition this chapter is headed by a full page wood-cut of Deadlock sitting ‘on his haunches, apart and morose.’ We have the Cheriton, the Culmstock, the Crowhurst (Kent and Sussex), the Courtney Tracey (Wessex) and men of the Dartmoor hunts.

So we have arrived at the final last long hunt, in which for forty pages and nine hours Tarka and the hound Deadlock are pitted against each other’s strength and wits as they run and swim and chase and flee the length and breadth of the rivers. Again Tarka is given away by the old grey-bearded man standing on New Bridge. But Tarka has a rest at Sycamore Holt – where Tarquol is also resting. The hounds find them, the two get separated and the hounds go after Tarquol, who puts up a tremendous and courageous resistance, creating mayhem in a farmyard, until he is finally seized by Deadlock and killed in a melee of hounds. Tarka’s son is dead.

Tarka is found again and the hunt continues. The hours are counted off like the striking of a mighty clock – there is a sense of doom reminiscent of Christ’s hours on the cross. Tarka rests.

At the beginning of the eighth hour a scarlet dragonfly whirred and darted over the willow snag, watched by a girl sitting on the bank. Her father, an old man lank and humped as a heron, was looking out near her. She watched the dragonfly settle on what looked like a piece of bark beside the snag; she heard a sneeze, and saw the otter’s whiskers scratch the water. . . .

For two minutes the maid sat silent, hardly daring to look at the river. The dragonfly flew . . . and settled on the water it seemed. Tarka sneezed again. A grunt of satisfaction from the old man, a brown hand and wrist holding a hat aloft, a slow intaken breath, and,

Tally Ho!

At the beginning of the ninth hour Tarka is tiring, he rests, then is seen again, but again escapes. The tide has turned. Hounds are called off, but just as they were leaving Deadlock sees the otter and leaps down the bank. They disappear under water: the hound only to surface in death – Tarka to be seen no more:

And while they stood there silently, a great

bubble rose out of the depths, and broke, and as

they watched, another bubble shook to the

surface, and broke; and there was a

third bubble in the sea-going

waters, and nothing

more.

A most dramatic ending for a most extraordinary book: a book written with the utmost care and attention to detail and based on months of meticulous observation. HW walked every foot of the ways that Tarka takes, and out of that familiarity he was able to write with a truth and freshness that is astounding. All the scenes in the book are real places and can still be seen today – most with very little difference from when HW himself walked those pathways. Today, following the ‘Tarka Trail’, it is possible to walk or cycle and follow that same mystical path that was HW’s vision. (There is a list of places and map references of ‘Tarka’s Route’ in HWSJ 16, September 1987, pp. 16-18.)

*************************

I would point out the setting of the print of those last lines of both ‘THE FIRST YEAR’ and ‘THE LAST YEAR’ sections, as shown above. This form, so redolent of a poem, is unfortunately lost in most of the subsequent editions. (I think such form in poetry was still well into the future – post Second World War?)

The innate poetic element in HW’s writing was recognised by Ted Hughes, Poet Laureate, in the address that he gave at HW’s Memorial Service at St Martin’s in the Field on 1 December 1977, stating that he had read Tarka the Otter when aged eleven,

and for the next year read little else. I count it one of the great pieces of good fortune in my life. . . . I recognised even then that it is something of a holy book, a soul-book, written with the life blood of an unusual poet. . . . In the confrontations of creature and creature, of creature and object, of creature and fate – he made me feel the pathos of actuality in the natural world. . . .

It is not usual to consider him as a poet. But I believe he was one of the two or three truest poets of his generation.

*************************

Back in 1921, HW had not been living in Georgeham in North Devon very long when a man he had met who lived nearby, an ex-soldier badly lamed from an injury in the war, approached him to help with the rescue of an orphaned otter cub whose mother had been shot by a local farmer. HW refers to this cub in one or two early items, but mainly the story of this incident was first written up as ‘The Man Who Did Not Hunt’, which was published in Pearson’s Magazine (USA) in March 1923, and for which HW was paid 18 guineas (£18/18/-). The story was then reworked and published as ‘Zoë’ in The Peregrine’s Saga, where the man is called Captain Horton-Wickham – fairly certainly a real name, as HW refers to him many years later in a diary entry, recalling his early friend (see AW, Henry Williamson:Tarka and the Last Romantic, p. 83). HW certainly played some part in the care of this young otter cub.

HW had also read The Life of an Otter by J. C. Tregarthen (1909) and thought he could have written a better story, as he confided in a letter to T. E. Lawrence (8 March 1928).

Having decided so to do, in order to gain accurate material HW took to following the local hunt, the Cheriton Otter Hounds, who hunted along the local rivers, the Taw and Torridge and their tributaries, whose waters meet in the estuary beyond Barnstaple. HW also spent some time at a zoo (not specified, but presumably Regent’s Park) where he could watch otters at close range, noting particularly how much they actually played with water.

When out with the Cheriton Hunt one day in the early summer of 1924, HW found himself walking next to a dark-haired, strikingly beautiful girl and her elderly father. HW quoted a phrase from Richard Jefferies’ famous story Bevis, and found both the girl and her father knew the book well. They were Charles R. Hibbert, one of the Hunt officials, and his daughter (Ida) Loetitia.

|

| 'Pa' Hibbert (far left) and Loetitia (right) at an otter hunt |

HW decided that here (at last) was the perfect companion to share his life. He proposed at the Hunt Ball on 24 August 1924, and they were married on 6 May 1925. Charles Hibbert features in Tarka as the man who raises his hat and cries ‘Tally-ho!’ to betray Tarka’s resting place during the last hunt: Loetitia (whom HW always called Gipsy) is the shy beautiful girl who sees the dragonfly settle on Tarka’s nose – and does not betray him.

At the time of his marriage HW had five books published, to increasing critical acclaim.

Their honeymoon was spent, after a few days on a farm next to Dunkery Beacon on Exmoor, visiting the battlefields of the trenches of the First World War, so bringing to the fore HW’s feelings about his own war experiences. I feel that these are inevitably bound into an underlying hidden theme to be found in Tarka (as into many of those short stories in volumes already published, as I have noted) making Tarka not just a superb tale about an otter but, further, an allegory of that war.

When, shortly after their honeymoon, Loetitia found she was pregnant, it was decided that Skirr cottage was too small and primitive. They arranged to rent Vale House just a few yards up the road. HW then settled down in earnest to write his otter saga. Today there is a blue plaque on Vale House announcing that Tarka was written there.

HW received a great deal of support and help from the Master of the Cheriton Otter Hounds (the ‘COH’), William H. Rogers. It is obvious that he was friendly with the family, visited their lovely home at Orleigh Court, and presenting copies of his books to Rogers’ daughters. HW worked in several real-life incidents to be found in Rogers’ Records of the Cheriton Otter Hounds (1925), although HW had probably been told these stories before the book appeared. A full account of the COH can be found in Tony Evans’ most interesting article ‘Chasing the Cheriton’ (HWSJ 37, September 2001, pp. 5-37), which shows many locations to be found in Tarka as still existing today. Several of the names HW gives the hounds in his story, and including their various characters, can be found among the various lists of COH hounds that appeared over the years: although ‘Deadlock’ would appear to be HW’s own name – although his character can be traced to a real hound. (The hound who took the part of Deadlock in the Rank film, who had make-up applied to change his features correctly, was a lovely friendly and rather lazy hound: he was called ‘Deadloss’ by us all!)

One story from the COH annals tells of a long hunt which started at 7.30 a.m. and continued until 6.30 p.m. which, although HW changed the details to fit his own tale, is the basis for the long, last hunt endured by Tarka.

William Rogers was also most helpful in matters of Hunt etiquette and ambiance: matters that HW was most anxious to have absolutely correct, so that he could not be criticised over details by the hunting fraternity. In recognition of this most generous support HW dedicated Tarka the Otter to William Rogers.

|

|

|

William Henry Rogers, Master of the Cheriton Otter Hounds (on the right in the lower photograph) |

|

|

|

The two photographs above are taken from 29 September 1928 issue of The Illustrated Sporting and Dramatic News (kindly provided by Glyn Shingler) |

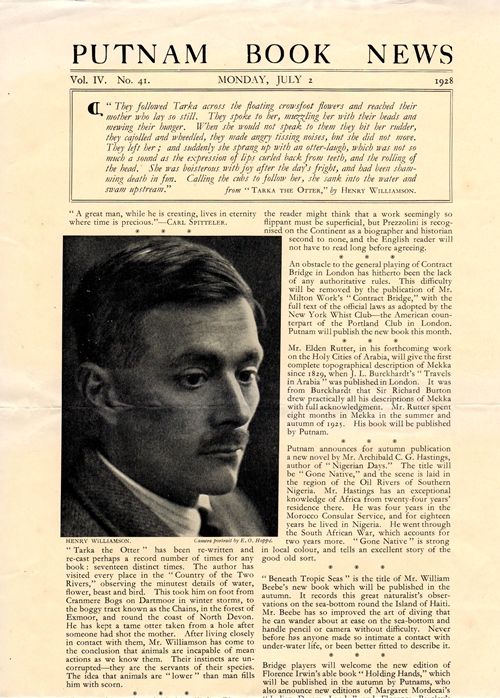

HW and Loetitia were invited to the wedding of Rogers' daughter Bridget, where the following photograph was taken; though the news item, about the author's success, made no mention that the couple were attenting a wedding, perhaps leading readers to believe that he always dressed in this manner, with 'faultless Lincoln Bennett'!

HW was also a great admirer of The Story of a Red Deer by Sir John Fortescue, younger brother of the Earl Fortescue, whose family seat was nearby at Castle Hill, in the tiny hamlet of Filleigh, North Devon, on the southern edge of Exmoor. In early 1925 HW asked Walter de la Mare if he would approach Sir John on his behalf to ask if he would be willing to write an introduction to Tarka. This approach proving successful, in due course HW sent off a typescript copy of his book to Sir John.

A letter from Sir John (from Windsor Castle, where he was librarian) dated 4 May 1925 (two days before HW’s marriage to Loetitia Hibbert – thus HW probably received it on the morning of his wedding, giving him much needed confidence) states:

I return your story . . . I read it once & liked it well; twice & liked it better. I am willing to write a little introduction for you . . . but I think the book striking enough to stand without need of any such prop. You have taught me more about otters than I ever dreamed of, & of many other creatures besides otters . . .

Sir John does suggest HW avoids ‘outlandish words’ and gives a couple of examples (‘autochthonic’ being one!). Sir John was currently writing a multi-volume History of the British Army and his work as Royal Librarian was quite arduous. One letter refers to ‘editing George III’s papers, & there are tens of thousands of them’. Another has a ‘PS’ written across a corner:

I reckon that my history has brought me in ¾d a line gross. I could never make my living with my pen – you can. [Permission to quote from Sir John’s letters was given by the Fortescue Estate at the time of my HW biography.]

On return from the honeymoon trip to the battlefields HW was busy honing and refining his story. The file of business letters shows that he was also looking for the best publishing deal possible, once again taking this on himself instead of leaving it to his agent, Andrew Dakers. I have already explained the problems that arose with Collins (see The Pathway entry), his original publishers. By September 1925 HW had placed this new book with Selwyn & Blount, but then Richard de la Mare (who had been best man at his wedding) warned him that the firm was in financial difficulties, and he withdrew. The book was finally placed with Putnam (who were also publishing The Old Stag).

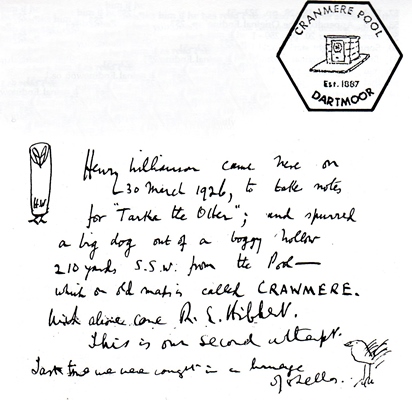

HW now went over all the details again, walking the river banks, visiting the various places where the major scenes were set and undertaking a great deal of revision to his tale. He noted details such as the plants growing in various places, and made diagrams of terrain to aid him with descriptions. For instance he walked up to Cranmere Pool (a remote, wild, boggy area high on Dartmoor, only reached with some difficulty) accompanied by his wife’s younger brother (Robert, but known as ‘Bin’ as if ‘Robin’: he features in the future Chronicle novels as ‘Sam’).

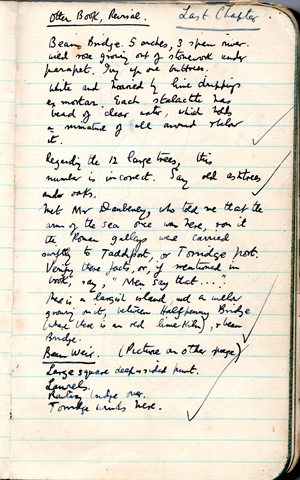

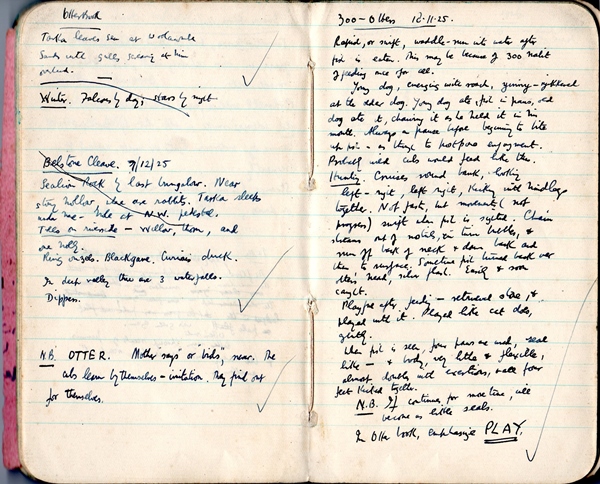

Pages of HW's notebook drafting passages and containing notes for Tarka:

Sir John sent the manuscript of his ‘Introduction’ in mid-August 1926, and HW certainly had a ‘finished’ typescript of the book at that time.

In November 1926 HW was staying with his friend S. P. B. Mais in Hove, Sussex. Mais had taken him to see Wilfred Meynell at nearby Greatham (see The Old Stag entry). But HW also went to see John Galsworthy who also lived nearby at Bury, obviously feeling depressed about the reaction he was receiving to his (as yet unpublished) otter book. This was probably a reaction from having finally sent it off to the publishers. He was understandably tired. The Old Stag had just been published and reviews of that were only just appearing. After HW left, Galsworthy wrote (with extraordinary kindness) two letters: one of encouragement to HW himself, the other to recommend HW’s writing to Edward Garnett, well-known critic and man of letters, publisher’s reader for the publisher Jonathan Cape, and who had established such writers as Joseph Conrad, D. H. Lawrence and E. M. Forster. Galsworthy stated: ‘He can see and he can write . . .’

This introduction was to have momentous significance in due course, for Garnett was a close friend of T. E. Lawrence (‘Lawrence of Arabia’). But the immediate response was that HW sent Garnett a copy of The Old Stag. Edward Garnett was immediately supportive.

To add to the difficulties that attended setting up the contract with Putnam in the first place, HW compounded the situation by continually prevaricating and trying to add clauses to cover every situation, while objecting to every suggestion. Constant Huntington and the book’s designer T.M. Ragg, or ‘TMR’ as he often signed himself, must have been very patient!

HW wanted Putnam’s to commission maps of the area roamed by Tarka, to be used as endpapers, from Thomas A. Falcon, an artist who lived in Braunton (Devon – HW’s nearest town). Falcon took a great deal of trouble, and HW loved the finished result: but Ragg stated that the thick lines when compressed down to the book size would be too ‘heavy’, and at the last minute (to HW’s chagrin and embarrassment for Falcon) he did not use them. (These maps were reproduced in HWSJ 16, September 1987, pp. 20-21, with accompanying note by AW, p. 19)

HW in his turn did not like the sample page Ragg sent, writing on it ‘I do not like this at all.’ He added that he wanted a simple and austere style, and a quiet and dignified binding.

The chief complication however was that HW, despite his extreme impecunious status, had decided to have a special de luxe limited edition of his book to be sold by private subscription. He concerned himself very closely with the details and was personally responsible for selling the copies. He had a prospectus printed which he sent out to as many people (friends, acquaintances, etc) as he could think of. This used up an enormous amount of time and nervous energy.

This limited edition of 100 copies, printed at the prestigious Chiswick Press, bound in full cream vellum and hand-made deckle-edged paper, was published in August 1927, price three guineas. Copy No. 1 was presented to Sir John Fortescue, the second retained for himself, third was bought by his mother, and the next three were bought by John Galsworthy, one by Walter de la Mare,, Edward Garnett, Siegfried Sassoon, another by Frank Swinnerton – and so the list went on. But sales slowed down and Putnam’s wanted it out of the way before they produced the trade edition. At one point Huntington urged him to send out a reminder letter to those who had not yet bought. Some of the money due came straight to HW, some went to Putnam: HW (obviously worried about money) inevitably began to wrangle about invoices, convinced he was not receiving his full dues: Huntington and others patiently reassured him.

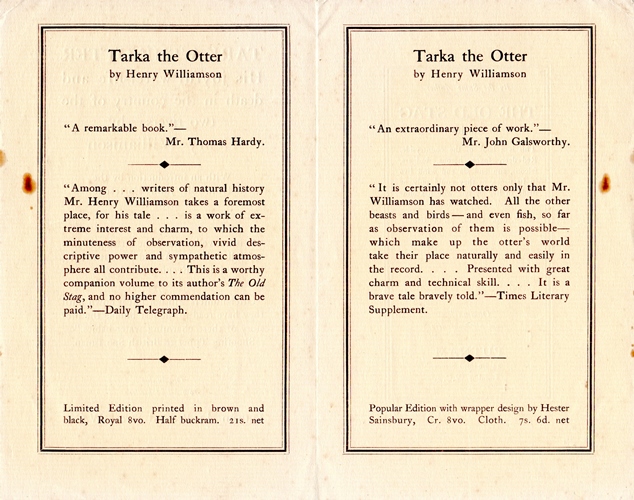

The second limited edition (1000 copies, half brown cloth/cream buckram, price 1 guinea) and the first full trade edition were published in October 1927. Putnam produced their own prospectus for these two editions:

Three days later no reviews had appeared and HW was very anxious and wrote in a notebook:

I say I don’t care what happens to it . . . But really I am alert as a falcon for appreciation.

So Tarka the Otter was launched. In fact reviews were favourable but there was not the immediate outcry that HW was so obviously hoping for. But Putnam took out advertisements for the book over the Christmas period, and the book was getting noticed:

When Dutton followed with the American edition early in 1928, the reviews there were very enthusiastic. (See Critical reception page.)

Soon after publication HW, en route on his motorcycle to see his Uncle Henry Joseph Williamson in Bournemouth, stopped for a rest in Dorchester. Realising he was outside Max Gate, the home of Thomas Hardy, with great trepidation he knocked at the door. He was invited to lunch – and before he left was asked to sign the visitors’ book. Afterwards he sent a copy of the limited edition (probably the one guinea version) to Hardy, who wrote to Putnam’s to say that he thought Tarka ‘a remarkable book’. HW recorded that he found Hardy ‘olde, olde’: two months later Hardy died.

Edward Garnett had (with great kind thought) sent round copies to several people suggesting they review the book and also, unknown to HW, had sent a copy to his friend T. E. Lawrence, then in India, stationed at Karachi with the Royal Air Force (supposedly incognito). At the beginning of February 1928, HW received a letter from Garnett enclosing a long and detailed critique of Tarka by TEL. TEL was under the impression that this was the author’s first book and that he was encouraging a novice:

I shouldn’t have written so much if the book was not, in my judgement, particularly worth writing about. . .

Very many thanks for sending it to me. It has kept me sizzling with joy for three weeks. The best thing I’ve met for ever so long. Fresh, hopeful, fecund, and so, so, careful. It is heartening to see a writer caring much for his words and chasing and chiselling them with such firmness. I hope he likes it well enough to persevere, for I shall look forward to reading him again: - apart from Tarka which I’ll read many times yet.

(The full text of this letter from T. E. Lawrence was first published in Men in Print: Essays in Literary Criticism by T. E. Lawrence, ed. Prof. A. W. Lawrence (Golden Cockerel Press, 1940): reprinted in Henry Williamson, Threnos for T.E. Lawrence & Other Writings, ed. John Gregory (HWS, 1994; e-book 2014). For the full correspondence between HW and TEL see: T. E. Lawrence: Correspondence with Henry Williamson. Letters, vol. IX, ed. P. & J. Wilson, with Prologue, Epilogue and notes by Anne Williamson,limited edition,Castle Hill Press, 2000.)

HW felt that Lawrence was a kindred spirit: he replied calling him his ‘twin psyche’, explaining the background to the writing of Tarka and sending a copy of The Old Stag. The two men began a regular correspondence and later TEL visited HW at Georgeham. (See Genius of Friendship, to be covered in due course.)

In mid-April 1928 HW received an even more gratifying letter: from Alice Warrender, founder of the Hawthornden Prize for Literature, announcing that the prize for 1928 ‘for the best imaginative work of the year’ had been awarded to Tarka. The judging committee consisted of Miss Warrender, Mr. Robert Lynd, Mr. Edward Marsh, Mr. Laurence Binyon, and Sir John (Jack) C. Squire. (Robert Wilson Lynd, 1879-1949, Irish writer, an urbane literary essayist and strong Irish nationalist, moved to London in 1901; Edward Marsh, 1872-1953, patron of the Arts, especially poetry – he helped Flecker, de la Mare, D. H. Lawrence, Graves & Blunden – published 5 volumes of Georgian Poetry (1919-22), literary executor of Rupert Brooke; Laurence Binyon, 1869-1943, poet and art historian – worked at the British Museum as Keeper of Printed Books; Jack Squire, 1884-1958, critic and poet, founded The London Mercury, a prestigious literary journal, in 1919 (HW wrote several items for this), knighted in 1933.)

HW was naturally elated. He sent a postcard to his wife’s maternal grandmother, Sarah Augusta Hibbert (Loetitia’s parents were cousins, both Hibberts), who lived in stately style on the outskirts of Barnstaple and who had been quietly encouraging, stating: ‘One has arrived.’

The prize was awarded on 12 June 1928 at the Aeolian Hall in London, presented most appropriately by John Galsworthy. HW and his wife stayed with Galsworthy and his wife for the occasion. Investigating background at the time that I wrote my biography of HW, it became apparent that, totally unknown to either of the two men, Galsworthy and HW were actually related, sharing a common ancestor, William Bartleet, a needle-manufacturer from Redditch (see AW, ‘Biographical Matters’ (HWSJ 32, September 1996) sub-heading ‘Frankley Hagley: an examination of the relationship between John Galsworthy and Henry Williamson’, pp. 50-55) It is interesting that both men wrote a long series of novels which (standing back) are about different branches of the same family. HW felt some competitiveness towards Galsworthy as a writer, and noted that he felt he could write better novels than The Forsyte Saga. But Galsworthy was unfailingly supportive of the younger writer.

Newspaper reports reveal that in his speech Galsworthy described Tarka the Otter as:

a truly remarkable creation. It is the result of stupendous imaginative concentration, fortified by endlessly patient and loving observation of nature. Henry Williamson has received as yet infinitely less credit as a writer then he deserves. He is the finest and most intimate living interpreter of the drama of wild life, and he is, at his best, a beautiful writer.

Miss Warrender is also reported as having made a delightful speech but: ‘the shy young man retreated from the platform without making a speech.’ This was remarked on in several reports, and obviously considered a little odd.

Miss Warrender had asked HW not to tell anyone about the prize so he had not even informed his publishers, who were now in some embarrassment (and somewhat put out) that they had not got a new printing ready to cover the immediate rush of sales. However, they wasted no time in advertising the book in their weekly Putnam Book News on two consecutive weeks, with Windles also getting in on the action:

The Hawthornden Prize brought HW recognition and fame. With the prize money of £100 HW bought a field on the hill above Georgeham at Ox’s Cross, where he built himself a Writing Hut which was to be his workplace and refuge for the whole of his life; he planted the boundaries with Monterey pines.

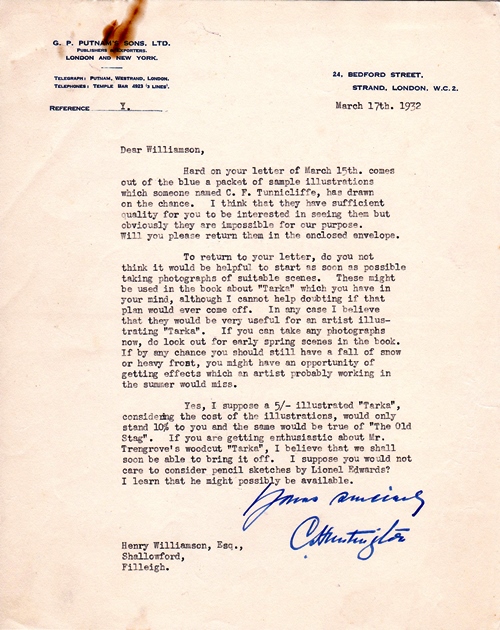

In May 1932 a young artist, Charles F. Tunnicliffe (1901–1979), approached Putnam with a proposal. He had read and enjoyed Tarka, and (apparently at his wife’s suggestion) sent some aquatints of otters with the proposal that he should illustrate a new edition. Constant Huntington put the idea to HW, who agreed, and on 24 May Tunnicliffe arrived at Shallowford (where by then the Williamsons were living) to meet HW and to see Tarka country for himself, and to start work on the illustrations – to be wood engravings.

After spending a few days at Shallowford, Tunnicliffe set off to work directly from the various scenes that occur in the book. This was the first book illustration task that he had undertaken, but his skill as craftsman and his talent for portraying the countryside and all its creatures were a perfect complement to HW’s words.

By 8 June Tunnicliffe was back at his home in Macclesfield, writing to report progress and enclosing prints of Rams Horn Pond with swallows, and of the honorary whip probing the holt with his pole. He continued to work and write to report progress enclosing prints of completed work. The two men collaborated very closely, as a large file of letters reveals.

On 15 July Tunnicliffe returned to Torrington, to work on the river there, especially at Canal Bridge, the birth and death location of Tarka. On Sunday 17 July, HW drove over to meet him and they went on to Dartmoor, where they walked up to Cranmere Pool, so that the artist could get that location absolutely correct.

Just over two months later, in a letter dated 12 August 1932, Tunnicliffe indicates that the work for Tarka was finished. But in the interim it had been arranged that Tunnicliffe would further illustrate new editions, to be uniform with Tarka, of The Lone Swallows, The Old Stag, and The Peregrine’s Saga, and that letter shows that he was already working on The Old Stag, for he enclosed six rough sketches.

The Charles Tunnicliffe illustrated Tarka was published later that year with 23 full page woodcuts and 16 line drawings as ‘tail-pieces’: the illustrated The Old Stag appeared in February 1933; The Lone Swallows later that same year; and The Peregrine’s Saga in February 1934. (There were many reprints of these books, including, in 1945, a new uniform limited edition of 500 copies each.) Tunnicliffe had never before drawn falcons at close quarters. HW sent him off to a professional falconer in August 1933. The artist was totally overwhelmed by this bird, sending HW a letter headed with his first sketch of the head of a peregrine (see AW’s biography, Henry Williamson: Tarka and the Last Romantic, p. 150) which is so powerful that the bird seems alive.

Tunnicliffe also illustrated the first edition of The Star-born. The surreal nature of the subject rather troubled him, and he wondered if he would be able to cope with it. On 12 December 1932 HW drove him over to Lydford Gorge so that he could work from the actual location. The artist rose superbly to the task and his wood-engravings complement the text in exceptional manner. Charles Tunnicliffe went on to be one of the great artists in the genre of bird painting, but he always recognised that it was his work illustrating HW’s books that first brought him fame.

*************************

Back to 'A Life's Work' Forward to 'Tarka the Otter: Critical reception' Forward to 'Tarka the Otter: the film and opera'