DANDELION DAYS

(Vol. II of The Flax of Dream)

|

|

| First edition, Collins, 1922 |

First published Collins, October 1922 (price 7/6d), 600 copies

Revised edition Faber & Faber, 1930

Dutton, USA, 1930

Many reprintings

Currently available from Faber Finds

This is the second volume of The Flax of Dream and represents ‘Boyhood’ in HW’s overall scheme.

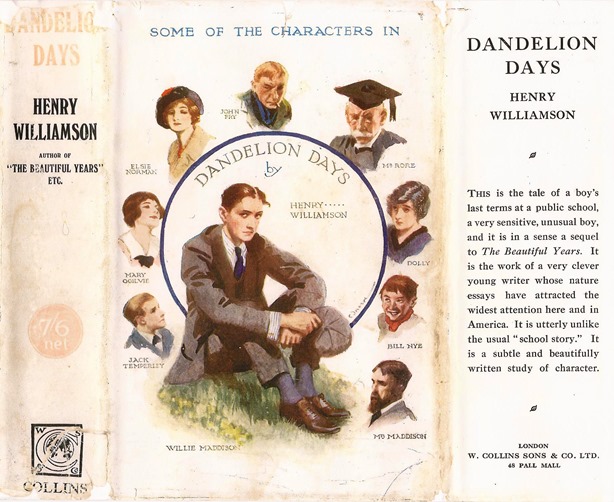

Dandelion Days continues the story of Willie Maddison’s young life, jumping several years from where we left him on his tenth birthday at the end of The Beautiful Years. As this book opens the sensitive lad is almost fifteen years old, but is rather weedy and looks much younger. His great friend Jack Temperley is younger by a year but much sturdier and developed. As rebellious adolescent boys they are enduring the confines of Colham School with its severe headmaster, Mr Rore (known by the boys as ‘The Bird’), and his idiosyncratic staff, whilst enjoying the innocent pranks and pastimes, such as roaming the countryside and collecting birds’ eggs, that occupy and enliven young boys (or did then); meanwhile dealing also with the uncertain turbulences of growing manhood and first love. The cover of the first edition has small vignettes of the various characters surrounding the main figure of Willie seated on the ground and staring dreamily into the distance, cap in hand – as simple and charming as the story itself.

In this volume Willie’s childish worship for Elsie Norman deepens, although she is patently not interested in him (the inference is that he is not of the same class as herself) and she finally rejects his seventeen-year-old declaration of love. Willie fails to see that it is her less sophisticated friend, Mary Ogilvie, who is devoted to him, but the closing scenes of the book show these two in empathy together, after a meeting on the Downs overlooking his home village. The seeds of the future have been planted, but a lot will happen first. Elsie is based on a girl who lived in the ‘turret’ house at the top of the same road as HW, Doris Nicholson, whom HW adored and yearned for throughout his school days and after: feelings that we can all identify with – the agony of first, and unrequited, love.

|

|

Doris Nicholson, identified here by HW as 'Elsie' |

We are introduced to Willie’s cousin, Phillip Maddison, from London, ‘the town cousin’, who comes to stay for a holiday. The introduction is precipitous – literally: Cousin Phillip, ‘a tall youth with a thin pale face’, trips while getting out of the train and falls onto the platform scattering all his belongings around him. From the earliest stages of HW’s writing career, he planned to write a further series of novels with Phillip Maddison as the chief character. Eventually written in the 1950s and 1960s, this is the fifteen-volume tour-de-force entitled A Chronicle of Ancient Sunlight. The characters of both Willie and Phillip Maddison, cousins in the novels, are based on HW himself, and it is amazing how the author mixed and matched various aspects and episodes in the two series, particularly in the school scenes, without alerting the reader to his juggling act! They are indeed two totally different characters.

A particularly hilarious story is Willie’s unexpected winning of the Bullnote Memorial Prize. The lead up to this is very detailed and told with relish. After the ceremony we find Willie parading around ‘his three immense prizes under his arm’. This derives from real life: HW was awarded the Bramley Memorial Prize for Divinity (Rev. Bramley being a former headmaster of the school), which seems very unlikely from what we know of this recalcitrant pupil! His prize was two huge volumes entitled The Bible in Art – one volume for the Old Testament and one for the New, each volume being a foot high and two and a quarter inches thick with content which would not appeal to a young boy! They weigh twelve pounds and one wouldn’t want to swagger with them under one’s arm for too long.

As Dandelion Days ends, Willie and Jack Temperley leave school. Willie is destined (reluctantly) to start a job in London at the Moon Fire Insurance Office, where we learn Cousin Phillip already works. He is to leave the next day. The two friends have a final moment of closeness as they enjoy a midnight camp fire and a feast together as they leave boyhood and comradeship behind. Then Willie goes off alone to say goodbye to his known world:

Willie walked into the shortening and ghostly shadows. At the edge of the spinney he stopped.

“I shall return,” he whispered to Aldebaran, fiery above the beech wood. “I shall not forget you, everything I love. I shan’t really be in London, only my body. Goodbye, old crowstarvers’ spinney, that will never again see Jim and Dolly . . . Good-bye, big wheatfield. Good-bye brook. Goodbye, owls. Good-bye dandelions. Good-bye, oddmedodds. Good-bye ---“

He leant against a tree, while a flittermouse passed round his head, squeaking. At last the ruddy star was clear again, and he went back to the waiting friend. Silently and with arms linked they passed down the pathway, leaving behind the wind murmurous in the trees and the silver-swaying wheat.

There the first edition ends. When HW prepared the revised edition, apart from excising most of the childish phrases in the book (some of which are rather excruciatingly puerile), he changed the end slightly:

The wheat was tall, and soon would be ripe for harvest: it was July, 1914.

Ominously prescient. He also added a very clever device in the form of an 'Epigraph' – a letter from Willie’s ex-headmaster of Colham, Mr Rore, to his ex-pupil, now 10943 Private W.B. Maddison. The first part of this letter, dated 29 October 1914, is based very closely (in places word for word) on one actually received by HW from his real headmaster, Frank Lucas. From this letter we learn that when the First World War broke out Willie Maddison had enlisted and was serving in a Territorial infantry battalion in the Ypres Salient. Mr Rore sends his sympathy on hearing the news that Jack Temperley has been killed in action. Charlie Boon, HW’s cousin and childhood companion of many happy holidays, one of the main sources for Jack Temperley, was actually killed in action later than this, on 19 November 1916, aged twenty-one: and another great school friend, Rupert Bryers (who appears in the books under his real name), was also killed in the fearful ten-day battle that was the attack on Lesboeufs on 15 September 1916. These deaths were a great blow to HW: he did not record much at the time, but there are many later wistful references to lives wasted.

|

|

|

||

|

Charlie Boon and HW: cousins and friends |

45153 Private John Charles Boon Machine Gun Corps |

Charlie's grave in Frankfurt Trench Cemetery |

|

|

|

||

|

The only three photographs known to exist of Rupert Bryers; the centre one is a detail from a photograph in HW's album. |

||||

|

|

Rupert's headstone in Guards Cemetery, Lesboeufs |

Although throughout the book Willie’s relationship with his father is constantly strained, with neither able to communicate with the other, and Willie quite harshly rejects his father’s company and offer of a slap-up dinner with champagne for that of his own friends on his last night at home, we learn in the Epigraph that in the breast pocket of his soldier’s uniform he guards a bundle of letters ‘stained and half-pulped with rain’, some from Elsie Norman’s mother (Mrs Nicholson did indeed write to HW at the Front), the others from his father. It is a subtle and clever exposition of reconciliation, showing that Willie does, actually, love his father deeply.

This later Epigraph allows HW to move on to his third volume more smoothly (showing his increasing skill in manipulating structure). He was not ready emotionally nor (as is obvious from his personal writings) sure enough of his ability at this stage to write about the First World War as he would want to. Its effect on his psyche was so deep, indeed it was the crucible that made him what he was, of which the metal was still too molten to be malleable. Further, he tells us in the original edition’s ‘Epistle Apologia’ that he will not be writing about the war in the next volume, as the reader might expect (and also reveals there an outline of the plot and main characters of the next proposed volume). He thus reveals that he has already written the next volume before this volume was published: already he had set himself quite a punishing schedule.

The title of Dandelion Days is derived from phrases to be found in Richard Jefferies’ Nature and Books, as is seen from the quotation on the title page which also pinpoints HW’s purpose to portray his ideas about the problems within (evils of) the current education system, for him the ‘cause and effect’, a theme permeating much of his basic thinking about life:

I hope in the days to come future thinkers will unlearn us, and find ideas infinitely better . . . let us get a little alchemy out of the dandelions.

This ‘dandelion’ theme also derives from Robert Bridges – ‘shock-headed dandelions, that drank the fire of the sun’.The opening section of the first edition quotes further from Richard Jefferies: ‘There is nothing in books that touches my dandelions.’ But HW had not at this time found the perfect section headings of the later revised edition that carried this theme to perfection – all again from Jefferies: ‘One Petal Out’, ‘Opening of the Flower’, ‘The Seed Loosening’, and ‘Over the Hills and Far Away’, all of which suggest the flowering of the spirit of its central character, Willie Maddison. The first edition unusually had no contents page, and the section headings were: 'The Gardener's Methods', 'The Opening of the Flower', 'Shadow and Sunlight', and 'The Passing of the Blossom'.

The members of the fictional school are all drawn from the real life, both staff and pupils, of HW’s own school, Colfe’s Grammar School, in Lewisham in south-east London. (The school still exists today – still considered as prestigious as it was then – though on a different site; the original site was bombed in the Second World War.) These scenes are often hilarious and sometimes poignant – above all, though, they are a true portrayal of school life as it was at that time. The names and personalities of the real-life counterparts have all been teased out and can be found in various issues of the HWS Journal, particularly No. 44, September 2008, which has a wealth of photographs and details about the school, its staff, and its pupils.

Dandelion Days caused somewhat of a furore among the staff of Colfe’s when it was published in October 1922. A review in the Colfeian by the Editor (himself an old boy of HW’s era) stated:

It is stark and savage caricature of actualities; truthful portrayal of the spirit of the actualities. Perhaps the printed description always seems more brutally unglossed than the happening itself (excepting warfare). Anyway we accept it as we think it is intended, and welcome a first class piece of literary work that should be read by everybody. But, lest others interpret it wrongly, we would advise the author . . . to take the air in a tin helmet and treble-seated trousers.

The Headmaster was a little hurt but dignified; Leland Duncan (an ex-pupil, then Governor, who gave HW much encouragement and attention) professed puzzlement at HW’s ideas on education, for he felt that the school had actually been quite liberal in setting up clubs and outdoor activities for the boys. R.A. FitzAucher, HW’s house-master and French teacher, again a kindly encourager, was tickled pink at his characterisation as ‘Rattlethrough’ and ended a letter ‘from one unworthy to tie up the buckle of your shoe’. But some of the other masters were totally taken aback and seemed never to forgive him – perhaps understandably, for it was all too soon after events, and HW did sail a little close to the wind in his characterisations! Today, of course, HW is known as an honoured alumnus of the school.

In the first edition’s ‘Epistle Apologia’ HW sets out his stall, his ideas and theory of education, which are cloaked within the cloth of his novel. That ‘the child is father of the man’ is writ large:

Nothing that happens afterwards [childhood and schooldays] will alter permanently that character. How it has been decided, you will read . . . how valuable have been the lessons of Colham Grammar School [i.e. basically learning by rote under fear of the cane] . . .; you must contrast the value of what is learned in the muggy atmosphere of the class-room with the value of sweet and lovely things seen in the countryside. It is to show this contrast, to exemplify it dispassionately and with truth, that I have written this book. . . . [The staff are not to blame – they too have been victims of a harmful method of education] . . . it is the wretched and false instructional system I would like to see considerably altered.

There follows a résumé of the plot and characters of the volume, then:

. . . You may think that I have failed to show that there is any basic wrong in the present system of cramming the immature mind . . . [but my intention is only to show] its unsuitability for one small boy.

Today we read these books (and probably always did) as a wonderful tale of a ‘time-lost’ childhood, rather than with any thought of educational theory and dogma: but it is a valid point for researchers to follow, and something that was at the heart of HW’s thinking even if it was all rather muddled and not properly thought through. HW would have been very influenced by his Aunt Mary Leopoldina’s views on education. She followed the theories of Pestalozzi (free-thinking – the child learning at its own pace from natural surroundings), and as in the later Chronicle of Ancient Sunlight series we learn that she set up a school following those principles, we must presume that she actually did so in real life.

Reviews of the first edition are not easily available. It wasn’t until after HW’s marriage in 1925 that a systematic filing of reviews was undertaken, and so for these early books one has to rely on ‘outside’ sources. The Bookman, in its lavishly illustrated special Christmas number for 1922, carried this Collins' advertisement, though, unlike The Beautiful Years in the previous year, no review:

Cuttings about the revised 1930 edition include:

John O’London’s Weekly (8 March 1930) – not signed but probably by Jack (Sir John) Squire (an important critic and literary figure) – praises it greatly:

. . . every detail of a boy’s life are recorded. The masters at school are seen objectively, their class mannerisms and their comic peculiarities are seized upon as only merciless boys seize upon them. . . . His boys are barbarians with streaks of humane feelings of which they are ashamed. Maddison is an unusual boy . . . his character is unformed but forming. “Dandelion Days” is a little masterpiece of imagination, of memory, and of prose. It is fresh and rational and lightened by a true sense of humour.

The Glasgow Herald (6 March 1930) really grasped the point:

A foreigner whose knowledge of this country was obtained entirely from its fiction might be justified in assuming that our only educational establishments are boarding schools. Mr Williamson's is one of the few stories of day-school life that we have encountered. It continues the career of Willie Maddison, whose childhood was the subject of "The Beautiful Years". Colham Grammar School, which Mad Willie attends, is almost a public school: that is, it has all the faults of the public school, the Philistinism, the harsh discipline, the hidebound subservience to the past, and the utter imperviousness to new ideas; but it lacks the virtues, having little corporate spirit, and substituting snobbishness for pride of caste. The masters are an unenlightened collection of petty tyrants whose lack of pedagogical ability is compensated by self-satisfaction and rigid suppression of the spirit of inquiry. Willie, not at all interested in the scholastic curriculum, but tremendously fascinated by the unresting life of the countryside, suffers agonies of humiliation under these Lilliputian Neroes and under his unsympathetic and unimaginative father.

But Mr Williamson, though he sees through the folly and sentimentality of regarding schooldays as a period of idyllic happiness, avoids the contrary error of presenting a youth tortured in his sensibilities by an uncomprehending world. Willie Maddison has his own life apart, and like all boys subject to persecution grows a protective skin. He has his calf love, doomed to disappointment though it be; he has his eggs, his feathered companions, his observations of Nature's many moods, and finally he has his great friendship with Temperley. This is a convincing study of the psychology of a schoolboy.

An anonymous cutting states: ‘The essential truth is there – the poignant sensibilities of adolescence . . . this is one of the best books about boys that I have ever read.’

Reviewing a later reprint edition in May 1950, the Glasgow Daily Record and Mail stated:

Most important among the new Penguins is Henry Williamson’s “Dandelion Days” (1s 6d), second instalment of the four-volume story of Willie Maddison. The first chapter “The Beautiful Years” has previously appeared as a Penguin.

The new book covers Willie’s last years at school, and no school story has ever been written with more certainty and tenderness. “Dandelion Days” is sad and sweet and dreamy and hilarious and it kept me up till the small hours sighing and chuckling and laughing out loud. Please read it.

A perceptive essay, presenting an interesting perspective from the 'other side', appeared in May 1947 in The London Schoolmaster, a monthly periodical published by the London Schoolmasters' Association:

*************************

The first edition of The Dream of Fair Women, among the advertisements at the back, includes this page of selected extracts from other reviews, mischievously selected, one suspects, by HW:

*************************

The scarce dust wrapper for the first edition, front and back:

Other editions:

|

|

|

||

| Revised edition, Faber, 1930 | First US edition, Dutton, 1930 | Penguin, 1950 |

Some other covers of different editions of Dandelion Days are shown at the bottom of The Flax of Dream page.

Back to 'A Life's Work' Back to 'The Beautiful Years' Forward to 'The Dream of Fair Women'