IT WAS THE NIGHTINGALE

(Vol. 10, A Chronicle of Ancient Sunlight)

|

|

| First edition, Macdonald, 1962 | |

First published Macdonald, 7 September (HW diary note) 1962 (18/-)

Panther, paperback, revised text, October 1965

Macdonald, reprint, 1985

Sutton Publishing, paperback, 1998

Currently available at Faber Finds

Epigraph, on title page:

And every stone that lines my lonely way,

Sad tongueless nightingale without a wing,

Seems on the point of rising up to sing

And donning scarlet for its dusty grey!

From The Flaming Terrapin,

by Roy Campbell

Dedication:

To Eric and Kathleen Watkins

The Watkins were friends of HW; Eric Watkins was a journalist on the News of the World, and was very helpful in patiently reading typescripts and correcting errors – time-lines, continuity, literal errors etc. as well as general support.)

The book’s title is a quotation from Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet (Act 3, Scene 5):

It was the nightingale and not the lark

That pierced the fearful hollow of thine ear.

The words are spoken as dawn breaks, after the one and only night together of their so brief marriage. The use of these words warns us that tragedy awaits HW’s young couple who married so impetuously: they are ‘star-crossed lovers’. The cover blurb of the first edition told readers exactly how this was to come about (which seems somewhat pre-emptive!).

HW also had great admiration for Igor Stravinsky’s opera Le Rossignol (The Nightingale – written as an opera, then turned into a symphonic poem, and later a ballet). This opera was composed in 1914, which HW would have found significant. It is mentioned several times in this novel: for example, Phillip, having just heard a nightingale, asks the garage man in France ‘Connaissez-vous “Le Rossignol” par Stravinsky?’ (p. 16)

But HW sets a far more enigmatic puzzle by his title page quotation. There is little within his archive to show that he knew Roy Campbell, but he obviously did, and greatly admired his poetry. Evidence of this is contained in ‘Roy Campbell: A Portrait’ which first appeared in The European in February 1959 (reprinted in Threnos for T. E. Lawrence & Other Writings, HWS, 1994, e-book 2014) and was a heart-felt tribute in response to Campbell’s death in a car accident in Portugal. Here HW states that he first met Campbell in 1924 and had been utterly captivated by the man, with his sun-lit personality and blazing blue eyes. But this does not really equate with an account by Alister Kershaw.

Campbell was a friend of Richard Aldington, with whom HW became friendly post-Second World War, and Aldington mentions Campbell a few times in letters to HW. It was these three writers that the young Alister Kershaw travelled from Australia to meet in 1947, and who was instrumental in bringing Aldington and HW together – and also appears to have introduced HW to Campbell, according to his own account.

Kershaw records a (seemingly first) meeting between HW and Campbell at the Savage Club (1947-ish), when HW said to Campbell: ‘Your work has been part of my inmost cosmos ever since Flaming Terrapin. It was Lawrence of Arabia, wasn’t it, who was responsible for the Terrapin being published and it was he who first told me about it’ (see HWSJ 28, September 1993, Alister Kershaw, ‘Henry Williamson', pp. 24-33).

HW’s copy of The Flaming Terrapin is marked as ‘1924’: he did not have contact with TEL until 1928, and Campbell is not mentioned in any correspondence between HW and TEL (but may have been in conversation when they met for the first time). HW may well have read a review either by TEL, or mentioning his admiration for the poem, which would have been well known in literary circles.

To clarify why HW used this seemingly obscure quotation needs explanation and background. As always, these quotations have their own purpose, however enigmatic they may at first appear.

Roy Campbell was born in South Africa in 1901, was well educated, loved literature and the outdoor life, and spoke fluent Zulu and other languages, including German. He came to England in December 1918, arriving at Oxford University in early 1919. Although this did not work out, he avidly read English Romantic and Elizabethan poetry and the philosophical works of Nietzsche. At Oxford Campbell met William Walton, the composer, who introduced him to the Sitwell family and Wyndham Lewis. Campbell did not like this group – ‘their “refined” manners and pretentious sickening writing’ – and was to satirise them in his poem ‘The Georgiads’ (1931).

Campbell does not seem to have written The Flaming Terrapin at Oxford, as HW suggests, but perhaps he started it there: he left Oxford in 1920 and travelled in France and the Mediterranean coast. In 1922 he married Mary Garman, whereupon his father cut off his allowance and they lived in penury in Wales. It was there that he wrote this long epic poem: ‘a humanistic allegory of the rejuvenation of man’. T. E. Lawrence found the poem very impressive and was instrumental in taking it to Jonathan Cape, who published it in 1924.

|

|

This rather difficult 1400-line rhymed poem tells the story of a mystic terrapin which draws Noah’s Ark into a revitalised world, symbolising the released energy of creative nature, described in images of volcanic flames, lightning and electric current. It is a ‘Rites of Spring’ in words.

A few lines further on from HW’s quotation are the words:

This sudden strength that catches up men’s souls

And rears them up like giants in the sky, [i.e. the creative spirit]

. . .

Stands visible to me in its true self

. . .

I see him as a mighty Terrapin

. . .

The Flaming Terrapin that towed the ark.

So the spirit of creativity in man is represented as a giant mythical terrapin – a Flaming Terrapin. A terrapin may seem an odd creature to have chosen for this role, but in eastern tradition it represents strength, longevity, endurance and courage, and is in fact a symbol of the universe.

However, the main power of the poem surely lies in its allegory of the First World War with its consequences for mankind, and is a call to the survivors of that catastrophic event to use creativity to heal the wounds: hence its appeal to HW.

The poem was acclaimed as a masterpiece and established Campbell’s reputation. Its clear message is that the First World War had destroyed the best and demoralised humanity, and it was the duty of survivors to put things right. The deluge in The Flaming Terrapin symbolises the War, and the Noah family ‘the survival of the fittest’ triumphing over the terrors of the storm to colonise the earth. The Flaming Terrapin tows the Ark, and where it lands creativity blossoms.

Campbell led a tempestuous life. He travelled between Spain, Portugal and England and became involved in the Spanish Civil War, where, being completely anti-communist, he briefly dallied with the ‘fascisti’ – and so earned an undeserved reputation. He was indeed ‘of the right’, believing in tradition and nationalism, and proclaimed agriculture (‘the tiller of the soil is timeless and enduring through eternity’, in poem The Serf) – but he was not a ‘fascist’. The connective web of ideas and empathy between Campbell and HW is very obvious.

Campbell tried to enlist in the Second World War, but was rejected due to current ill-health. In due course he worked for the Army Intelligence Corps in East Africa (his skill in languages coming to the fore), but was eventually discharged due to ill-health (injury and malaria) with an excellent military record. Post-war he was disgusted to find ‘half Europe given to the USSR’.

He then worked for the BBC as a producer of talk programmes. His appointment was greatly resented by the intelligentsia set, who tried hard to get him removed. In 1952 he and his wife moved permanently to Portugal. In April 1957, travelling back from Spain, they were involved in a car crash when nearly home. Campbell died at the scene. Edith Sitwell (epitome of the artificiality that Campbell so disliked), acknowledging his worth, said: ‘He died as he had lived, like a flash of lightning.’

So, to come back to HW’s use of this quotation: he is telling us that not only is his story by its title about the untimely and tragic death of Phillip’s young bride in childbirth, but that it is also about a man still obsessed and traumatised by his experience of war: ‘donning scarlet for its dusty grey’ is the stain of blood on the grey dusty tunics of innocent young soldiers – the ‘nightingales’ of a whole generation, the voices of so many ‘poets’ that will never sing because their tongues have been stilled. Phillip’s path through life is full of ‘every stone that lines my lonely way’. HW is laying down a marker for Phillip’s character and his actions, and so of course for his own. The war may be over, but we are still dealing with a ‘war’ novel. The trauma has not gone away. It has become buried in the psyche and affects all future actions. It is ever present. But Phillip (HW) has taken on the mantle of ‘survivor’ as seen in Campbell’s poem – and must, through striving with creative power, heal the wounds of mankind caused by war or actually causing the war.

*************************

It Was The Nightingale opens with Phillip Maddison and his bride Barley enduring the long hard winter of 1924 in Valerian Cottage at Malandine in South Devon. Phillip struggles with his war book without success. In April Barley suggests a visit to her mother Irene in the Pyrenees.

En route, they find an orphaned baby otter which Barley adopts, and she tells Phillip that he is to be a father. Returning to England their cat accepts the otter into her litter of kittens and it flourishes.

The time arrives for the baby to be born, but there are problems: a difficult labour and incompetent help. Phillip in a state of acute anxiety gets Barley to a nursing home, but later finds her sitting up nursing the baby, icy cold and unconscious. When she is moved she haemorrhages, and although Phillip offers his blood, it is too late and she dies before this can be carried out.

Leaving the baby in the hospital, Phillip returns home in desolation, blaming himself. After the funeral he goes off to Willie’s cottage in North Devon. On his return the otter is missing. After a frantic search he finds it in a trap, but on releasing it, it runs off. His search is in vain.

Grieving, he visits his mother’s original family home in Cross Aulton, now occupied by Uncle Joseph and family, and one night hears a nightingale which gives him the release of tears. Deciding to visit Irene in Laruns (she has been unable to attend the funeral of her daughter), they grieve together. Phillip then leaves to visit the battlefields where he thinks of Willie, Spectre, and Barley, all dead; but beside the River Ancre he again hears a consoling nightingale.

Returning first to see his parents, then on to Malandine, he finds the nursing home staff have turned against him, and he decides to leave for good and take over Willie’s cottage in North Devon. Here he makes friends with Mules the postman, his wife and daughter Zillah. Mary Ogilvie, the girl whom Willie loved, contacts him and invites him to join an Otter Hunt, where he meets her cousin, Lucy Coplestone. In due course she agrees to marry him (and be a mother to baby Billy). He meets her father and three brothers and ‘Grannie’, Mrs Chychester.

His agent tells him his work is not selling. This greatly depresses him, but Uncle John, Willie’s father, reminds him about the family farm and he decides to take this on. Meanwhile Lucy’s three brothers raise mortgages against their future inheritance in order to improve their workshop. They are good engineers but useless at finance, and so all is a muddle.

Phillip visits his parents to inform them of the arrangements for his wedding, and Uncle Hilary finalises the farming project. Phillip frantically tries to finish his otter story and sort out the cottage before the wedding: seeing his plight, Zillah and her mother take over.

The wedding takes place and Tim, the youngest of the brothers, drives them in his Trojan to a farm on Exmoor in a violent downpour. That night Phillip forces himself on his inexperienced bride to her distress, but they then spend a happy week on Exmoor looking for dippers’ nests etc. The plan is then to visit the battlefields, but this gets abandoned, and they return to Rookhurst to camp and start the farming project.

*************************

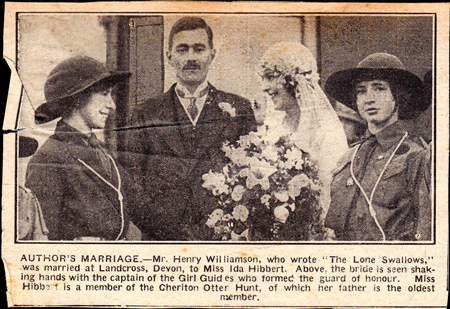

It is perhaps useful to state here that in real life there was no early ‘first’ marriage with a wife who died in childbirth. The child ‘Billy’ is William – Bill, known as 'Windles' when young – born in February 1926, the firstborn of the marriage in May 1925 between Ida Loetitia Hibbert (who is Lucy) and HW. Bill died in July 2014.

Although the characters of Irene Lushington and her daughter Barley are possibly based on people HW knew at that time, there is no concrete evidence of their existence that I can account for. Some research has been done that seemingly proves their existence, but this has not been substantiated.

Barley seems to be a fictional fulfilment of HW’s obsessive need, and search, for a ‘perfect’ female being – a being who almost certainly cannot exist – and because HW knows this in the depth of his psyche, she has to be killed off. ‘Barleybright’ was the name he gave to Ann Edmonds in his coup de foudre love in September 1933. Although HW may be obliquely referencing this episode here, it has to be said that in no way does the fictional Barley resemble Ann Edmonds’ character.

*************************

There is very little archive information about the writing of It Was The Nightingale. HW’s main diary for 1961 is almost blank. His appointment diary shows his usual frenetic travelling to and fro – London, talks (BBC) and lectures, meetings (PEN, WCWA, agents, literary contacts etc.), articles, interspersed with various family visits and social occasions.

The only real reference to his ‘serious’ writing is the entry (blank since January) for 2 May 1961:

My entries this year have been almost nil because I have been working on an average 75 hours a week for 7 days a week. I have written and revised several times No. 10 novel [It Was The Nightingale] and have started No. 11. No. 9, the Moon, is due in proof on 15 June.

Such is the overlap of the various phases of this treadmill task. There is no let-up in the intensity.

HW did spend two weeks in Ireland at Bellarena, John Heygate’s estate, to attend the wedding of John’s step-daughter Ros to John Harvey (of the sherry firm). On 24 August he noted a visit to Alan Clark (MP, historian and diarist) in Cornwall. No details are given but we know Alan Clark was an admirer of the Chronicle of Ancient Sunlight as ‘still far the best illustration of history as fiction that I have ever encountered’ (article in the Guardian and also the Evening Standard, 1994).

On 8 September HW again flew to Dublin, rather oddly to meet up with Kenneth Allsop (there on holiday), who was to do an article for the Daily Mail ‘on me and my books’ (this is untraced to date). While there HW visited Tralee – ‘nice visit’ – but records tremendous gales and 87 killed in the Shannon estuary. (This was Hurricane Debbie, the most powerful cyclone on record to strike Ireland, causing widespread damage and uprooting tens of thousands of trees and powerlines. In fact 18 people were killed and at least 50 injured in the Irish Republic and Northern Ireland, while the hurricane also caused a plane to crash in the Azores, killing 60 people.)

Returning on 15 September, the following day his diary notes (this will have been an ‘advance’ notice to himself of the deadline date):

800-900 words ‘On Writing A Chronicle of Ancient Sunlight’ for Miss P. Pearce, BBC, of World of Books, to be recorded. [This is ticked in red with note: ‘sent 15th Sept.’]

This essay was recorded by HW in London on 3 October 1961, being broadcast on 7 October in the ‘On Writing a Novel Series’. The talk is reprinted in Pen and Plough: Further Broadcasts (ed. John Gregory, HWS, 1993; e-book 2013), where John gives further details about this script in his introduction. Also see John’s excellent article, ‘Henry Williamson and the BBC’, HWSJ 29, March 1994, pp. 5-32, which gives a full background to HW’s broadcasts from the correspondence between various BBC employees and HW. Here John reveals that Philippa Pearce was not entirely happy with HW’s original script. She wanted more punch to it: ‘I am thinking of your seeing yourself “part of the world deteriorating through frustration of the social instinct”’. This article is reprinted as the Afterword in the e-book edition of Spring Days in Devon and other Broadcasts (ed. John Gregory, HWS, 2013; e-book 2013).

HW ends this broadcast essay with the words:

The theme of the series is that love is courage, is honour, and for the loveless redemption through love, which gives harmony and by which art, the flower of human living, comes to being. This, of course, is nothing new, it is the basis of the teaching of Jesus of Nazareth, and other visionaries who have lived and learned by suffering, among men.

It is interesting to compare this essay with ‘Some Notes on [Flax and Chronicle]’ as published in The Aylesford Review, Winter 57-58, Vol. II, No. 2, where HW also expounds on the ‘love and loveless’ theme. (See my entry for Love and the Loveless, where a full explanation of this phrase is given.)

It Was The Nightingale seems to have been given little attention by the critics (unless material is missing from the archive). It may be that perhaps the content appeared a little dull and slow-moving after the dramatic sequences of the war volumes and the immediate aftermath when it first appeared. However, seen within the context of the whole Chronicle it falls into its proper place, and indeed reveals a great deal about Phillip, his state of mind, and his thoughts at this time. It also contains a great deal of social background of life at that time, which quietly threads throughout. One of the interests is, as always with HW, seeing how he threads real life details into his fictional tale. Above that, it is a compelling story in its own right and can, possibly unusually, be read as a single unit – that is, its particular content is contained within itself.

*************************

The book is divided into five parts.

Part One: LARK AND NIGHTINGALE

This part title reinforces the Romeo and Juliet theme, but its fronting quotation is from what is nowadays a fairly obscure long epic poem The Bride of Abydos (1813) by Lord Byron (1788–1824) – unfortunately misspelt as ‘Albydos’ in the first edition. HW marked it for correction but the error has been continued, other than in the cheap Panther paperback.

‘When Love, who sent, forgot to save,

The young, the beautiful, the brave.’

To fully understand HW’s purpose in using this quotation it is necessary to have a little understanding of the actual poem.

The Bride of Abydos is a ‘Turkish Tale’ of love and violence. Young Selim is in love with the beautiful Zuleika, daughter of the tyrannical Pasha Giaffir, who had murdered his brother (Selim’s father) by poisoning. Thus we have echoes of Hamlet (the major theme of The Gold Falcon), but also the poem is in effect a version of Romeo and Juliet – the inherent theme of this particular novel – so this seemingly oddly placed quotation does actually fit well here. Selim had escaped and is now a pirate, but is smuggled into the harem as a son of Giaffir. (Complicated intrigue!) Zuleika is described thus:

The light of love, the purity of grace,

The Mind, the Music breathing from her face,

The heart, whose softness harmonized the whole,

And Oh! that eye was in itself a soul!

(That could be a description of Barley.) Selim explains his situation and asks Zuleika to run away with him, but Giaffir arrives with his men and inevitably kill him. Zuleika then dies of a broken heart. The cruel tyrannical Pasha is left alone with his horrified grief. All very Romeo and Juliet.

Interestingly, Byron’s poem is itself fronted with a quotation from Burns:

Had we never loved so kindly

Had we never loved so blindly

Never met or never parted

We had ne’er been broken hearted.

HW no doubt considered that too obvious to quote for his own purposes, but there are several phrases in Byron’s poem that would have had resonance. Canto I actually opens with:

Know ye the land where the cypress and myrtle

Are emblems of deeds that are done in their clime?

Violent death is to be the theme. We are back with that resonance of the war dead suggested by the Campbell quotation that forefronts the book. Woven throughout Byron’s poem is the idea, or concept, that the souls of the dead inhabit birds – a deeply held belief of Eastern peoples. This is a theme in several of HW’s novels, for example, The Pathway, The Star-born, and The Gold Falcon. White birds are a particular icon for HW – barn owls appear frequently (his own owl device that he used for a colophon), but he also specifies ‘white birds’ as having mystical qualities in various places. (See HWSJ 36, September 2000, p. 71, where there is a short analysis of this theme.)

Canto II of Byron’s poem opens:

The winds are high on Helle’s wave

As on that night of stormy water

When Love, who sent, forgot to save,

The young, the beautiful, the brave.

(The last two lines are those quoted by HW.)

And a few lines further on:

Escaped from shot, unharm’d by steel

. . .

Within the place of thousand tombs.

This reinforces the idea of the death of innocent youth: here in this novel, but also those killed in the war – ever present in HW’s mind. It is the personification of FATE (or death) at the hand of an all-powerful corrupt entity.

But Byron returns to his concept of the bird that sings at night:

To it the livelong night there sings

A bird unseen . . .

For they who listen cannot leave

The spot, but linger there and grieve.

(It is singing the name of the loved one – Zuleika.) The bird was, of course, the nightingale.

Thus in this ‘novel in verse’, The Bride of Abydos, is encapsulated the whole of HW’s own main themes or preoccupations: love and death – one might transmute that to ‘War and Peace’.

*************************

So we turn to the story itself. HW had a great facility for opening paragraphs that immediately draw one in to the particular story. It Was The Nightingale opens:

They had been married in January, and the winter was glorious at first, with snow falling to a depth of six to ten inches all over England; one of those seasons which occur about every ten years, when Europe is scoured by winds from the North Cape to the Mediterranean; when strange birds, with staring eyes and feathers the hue of frost and fog, are driven far from their sub-arctic grounds in search of food upon a white continent.

(The reader is meant, of course, to recognise the connection to the winter scene in Tarka the Otter.)

Phillip and Barley have endured this hard winter in the somewhat basic Valerian Cottage (in the fictional ‘Malandine’, now established as South Milton on the south Devon coast – see the preceding volume, The Innocent Moon). Phillip wants to write his war book, which haunts him, but makes no progress. At the end of April, when the swallows have arrived back, Barley suggests that they visit her mother at Laruns, in the foothills of the Pyrenees.

Note that it was in May 1924 that HW went on a walking tour of the Pyrenees in the company of two literary friends, D. B. Wyndham Lewis and J. B. Morton. (I suspect that he used ‘Laruns’ because of its onomatopoeic association with the name by which T. E. Lawrence was known by the Arabs: ‘El Aurens’.)

The pair set off on the Norton motorcycle, first visiting Aunt Dora in Lynmouth (thus keeping this important thread in mind), and then on to Gaultshire, to see the area of his boyhood holidays with his cousin Percy (Charlie Boon in real life – killed in the war), but it has all changed and they continue on to the county town, where, at the cathedral, they find the Gaultshire Regiment are about to lay up the Colours. The description here is very moving.

It was a chastening moment when the voices of the choristers soared up into the contained light of the stone-arched roof. He felt to be free of himself, to be sharing the feelings, still existing, of the men and women who had stood there through the centuries and bowed their heads to the truth of life; as he was now; as they were then; [‘As it was in the beginning, is now, and ever shall be.’] Life was of the same moment of Truth from century to century; the Spirit was from everlasting to everlasting.

In that feeling it was neither strange nor ironic that the Colour Party marched up the aisle with fixed bayonets, corks on the points, to deliver the Colour to the Bishop, to receive the benediction. Then the base of the staff was placed in a sconce on the wall; there to yield, in dusty Time, its silks and dyes to the summer airs which had made them, under God, the spirit of flower and winged insect, the Spirit of Evolution, which also worked through the mind of Man.

On Sunday, 16 November 1924, HW did indeed attend a service at St Alban’s Cathedral for the presentation of the Colours of the 1st Battalion of the Bedfordshire & Hertfordshire Regiment (the two had been amalgamated in 1919).

Continuing on their journey, the pair cross over to France where, while waiting for their train, they see a garage, where they purchase a ‘voiturette’ of the marque ‘Bédélia’, a narrow, rather racy-looking light car affair which cost them 5,500 francs (7,000 francs are stated to be ‘sixty quid’ – so the cost was about £47). It is hearing a nightingale that persuades Phillip to clinch the deal! HW may indeed have seen such a car around that time, though he never owned one – but he researched all the details on how to drive it, and the complicated way in which the gear is changed, in Kent Karslake's Racing Voiturettes (Motor Racing Pubns, 1950):

At the front of Racing Voiturettes he wrote:

Phillip and Barley drive in this eccentric vehicle to the battlefield area of St Omer, Arras, Cambrai and Bourlon Wood:

The wreckage of Bourlon wood was covered by green scrub. Far away on the horizon lay the old Somme battlefield, like a distant sea fretted by waves of wild grass and poles of dead trees. He longed to be once again in the desolation of that vast area, so silent, so empty, so – forsaken.

But Phillip cannot face this desolation: ‘“Barley, let’s go on south. I don’t want to see the battlefields.”’

Stopping for lunch and a river swim on the way south, they find an orphaned otter cub which Barley adopts. So we have a further re-telling of HW’s original story of a tame otter, which first appeared as ‘Zoë’ in Pearson’s Magazine in 1923 (reprinted in facsimile, HWSJ 31, September 1995, pp. 71-3; another version appeared in The Listener, November 1936, reprinted HWSJ 33, pp. 67-9 and in Spring Days in Devon (ed. John Gregory, HWS, 1992; e-book 2013.) Later Barley tells Phillip that he is going to be a father.

The pair spend a few days on the Camargue (where HW had spent his honeymoon with his second wife Christine, when they stayed with Richard Aldington at Le Lavandou in April 1949 – and indeed the aborted battlefield visit described here also refers to this 1949 visit). They then continue on to the Pyrenees.

Surprisingly the visit is completely glossed over: they arrive, and by the next paragraph are on their way back to England, having sold Bédélia for 7,000 francs and smuggling the otter through customs.

Back at Malandine the otter cub is absorbed into the cat’s litter of kittens and flourishes. The couple make friends with local residents Georgie and Boo Pole-Cripps, who have a baby son ‘Maundy’; Georgie is a would-be journalist, and is portrayed as a total bore. They were in real life Aubrey and Ruth Lamplugh, who lived in Georgeham, and whom HW knew well. (Their daughter Lois notes in her book about HW, A Shadowed Man, that her father took a postal course in free-lance journalism in the ’twenties, just as Georgie does here.)

On 4 August 1924 Phillip reads of the death of Joseph Conrad:

Phillip avoided the others on the sands, and walked alone on the cliffs, his head filled by thoughts of the dead writer: noble Joseph Conrad, his secret sharer of many winter nights in the cottage. Now he had crossed the shadow line, having passed through the heart of his own darkness to – what? At least to the immortality of men’s minds.

There are several allusions here, recognisable to any Conrad reader: his short story ‘The Secret Sharer’ (1909); and his novels The Shadow Line (1917) and Heart of Darkness (1899), the latter based on Conrad’s time as captain of a river steamer in the Congo.

In the novel, Georgie Pole-Cripp’s father is a reverend gentleman, as was Aubrey Lamplugh’s father. The note he writes about Phillip’s novel is a close version of a note written to HW by the actual vicar of Georgeham, the Reverend Rose.

The critique was written on a half-sheet of paper in a tenuous, slanting fist. . . . when they had finished it both laughed so much that Phillip had to sit down with weakness.

A work of real literature sparkling like a jewel of many facets. A story of the longings of youth in a maze of sophistry and materialism trying to find its feet. A work revealing deep suffering and aspiration, an opal. The inherent poetry glows now like the ray of a ruby, now like the glint of a diamond. It attracts by its sincerity, entrances with its psychology, it inspires by its pilgrimage of a lost soul's search into the falsities of the pagan spirit, it intrigues by its interplay of character, it stirs with its pathos, it wins regard by its fortitude, it repels by its pessimism, and nauseates by its utter ignorance of the manifold ways of the Almighty.

Phillip’s mother Hetty and Doris and Bob Willoughby come to stay (as did HW’s mother, sister Biddy and her husband-to-be Bill Busby). A séance is held and Bob, rather sinisterly, appears to turn into Percy Pickering (the cousin with whom Biddy in real life was deeply in love, and with whom Busby had been close friends). But all is interrupted by a chimney fire in the Pole-Cripps’ cottage, as their containers of whit-ale explode in the heat of the roaring fire.

The time arrives for the baby to be born. Neither parent knows what to expect, and the reader senses that Barley is in difficulties from the start; but the midwife says not to worry. That evening Dr McNab is playing skittles in the pub – the Ring of Bells – and remains unconcerned. Georgie and Boo offer to take Barley to the nursing home in their Trojan (as indeed did the Lamplughs when Loetitia went into labour for the first time). Phillip is in a state of acute anxiety, but does not know what to do for the best – and so does nothing.

At dawn he returns to the nursing home (on his Norton) and using a ladder he gets into Barley’s room, where he finds her sitting up in bed holding the baby. She is barely conscious and very cold. Urgently removed to the Cottage Hospital, she haemorrhages when moved. Phillip gives his blood for transfusion but it is too late.

Someone lifted him up from his knees beside the bed, a man in darkness who had come to the end of the world.

Leaving the baby at the Cottage Hospital, Phillip returns to Malandine. Distraught, he blames himself for her death. His mother comes down for the funeral, but Irene has been called to her own ex-husband’s death-bed.

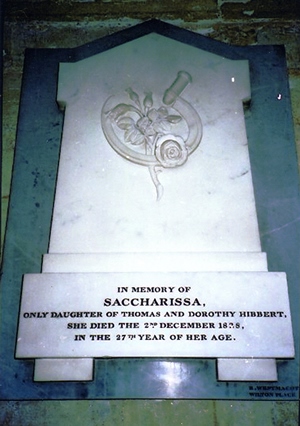

He ordered a small stone of white marble, with her name on it, Teresa Jane Maddison, aged 19 years, and below, carved from the stone, a device of reaping hook severing a rose bud from the stem.

This poignant epigraph (first mentioned in On Foot in Devon, 1933) is taken from a memorial to Saccharissa Hibbert to be found on the wall of Exeter Cathedral. This young girl was a distant relative of HW’s wife in real life, Ida Loetitia Hibbert, whose parents had made their fortune in the sugar fields of Jamaica (hence, probably, her name). It seems she had died suddenly, reason unknown, while on a visit to Exeter in 1828.

A notice in the Exeter Flying Post on 11 December 1828 stated:

On Saturday morning, the remains of Miss Saccharissa Hibbert were removed from her lodgings, Dix-field, for interment in the Cathedral. The funeral procession on the occasion was of a very handsome order. [Information courtesy Devon Record Office.]

Phillip goes off to Willie’s cottage in North Devon. On his return he finds the pet otter is missing. Searching frantically (for Barley had loved it) he eventually finds it caught in a gin trap. While being released it bites him, and runs off, leaving behind two claws.

In deep grief, Phillip goes to stay with his relatives at Cross Aulton. So back into the tale come his cousins Arthur Turney, Joe (Joseph), and May, and their parents, living in the original Turney family home. While there he writes a story about an African baboon (‘T’chakamma’, printed in The Old Stag, 1926) and a hunted hare (‘A Day with the Jelly Dogs’, also in The Old Stag).

Phillip walks about at night on the Downs thinking of suicide, but one night he hears a nightingale, which finally gives him the release of tears. He resolves to pull himself together, to visit Irene and then go on to the battlefields and quotes:

Speak for us, brother, the snows of death are on our brows.

These unattributed words are from ‘A Lament from the Dead’ by Walter Lightowler Wilkinson. Born in Bristol in 1886, his father worked on the Great Western Railway and his mother died while he was still a child. Showing striking literary gifts, though weakly in health, he was introduced to Mrs William Sharpe, widow of the then well-known author Sir Alexander Nelson Hood (Duke of Bronte), who adopted him. Wilkinson enlisted in September 1914 and, as a lieutenant in the 8th Argyll & Sutherland Highlanders, was sent out to France in January 1917. He was killed in the attack on Vimy Ridge on 9 April 1917. The poem was written a few days before he died. HW’s words are not all a direct quotation: but the poem reflects exactly what was in his own heart and mind. The poem also mentions a lark which further follows HW’s own theme here – and as a central symbol within his war writings.

At Laruns Phillip and Irene grieve together, and she tells him not to blame himself. But restless, he goes on to the battlefields: ‘He took a slow train to Arras, to seek upon the battlefields the friends of his youth.’

Part Two: PILGRIMAGE

‘God made the country, and the Devil made the towns.’

Old Saying

The origin of these words are usually attributed to William Cowper (1731-1800):

God made the country, and man made the town. (‘The Task’, 1785)

But a similar thought had previously been expressed by Abraham Cowley, 1668):

God the first garden made, and the first city Cain.

And later even more pithily by E. E. Bradford (1810-1911) in ‘Society’:

God made the country, and man made the town – and woman made society.

So – yes – an ‘Old Saying’! HW had used a similar phrase on the title page of the third volume of this series, Young Phillip Maddison. However, its use here does not seem very apt other than that HW did not like much of the rebuilding of the battlefield towns – or rather that people were using the reparations act to feather their own nests – and so, ‘evil’.

Chapter 5 here, ‘Two Battles’, is a reprise of the earlier The Wet Flanders Plain, encompassing HW’s visit to the battlefields with his bride (Loetitia Hibbert – ‘Gipsy’) in May 1925. Here Phillip is alone, grieving for Barley, and thinking of Cousin Willie, who had worked for the War Graves Commission at the German Concentration graveyard, and of Henri Barbusse’s book Le Feu (1917 – a seminal influence on HW), the scene of fighting in the Labyrinthe. Phillip stays with the ‘widow of Roclincourt’ (see The Wet Flanders Plain for HW’s account of his stay at the widow’s).

He then moves on south to the area of the Somme to Achiet-le-Grand: the area where HW had been in action as Transport Officer in spring 1917. It is here that we read of the crafty scheming involved over the reparations (the Devil making the towns). He continues to La Boiselle, and there beside the Ancre he again hears the nightingale:

It seemed to be hesitating; the same note was repeated among the hazel wands and ashpoles, a note low and plaintive. Next, three high and frail strokes of song and then another pause. Suddenly the green shade around him seemed to shake with the liquid notes of the bird’s passion . . .

The nightingale’s song was immortal; a symbol of human longing as old as that longing in man for love and immortality.

HW again mentions here ‘Stravinsky’s opera heard from the Dove’s Nest at Covent Garden.’

Phillip’s thoughts state, in effect, that he has to find himself – find that part of himself lost or marred by the war. This is an important passage which should be noted and it occurred to me that the whole of the Chronicle of Ancient Sunlight possibly expresses HW’s own search to find himself: i.e. to exorcise the effects of the First World War and to reveal an inner and central truth.

Where was the lost part? . . .

For years the lost part of himself had lurked in the marsh, seeing wraiths of men in grey with helmets and big boots, wraiths of men in khaki, laden and toiling, wraiths of depressed mules sick with fatigue and mud-rash, walking in long files up to the field-gun batteries, past wraiths of howitzers flashing away with stupendous corkscrewing hisses upwards, wraiths of pallid flares making the night haggard, while bullets whined and fell with short hard splashes in the gleaming swamps of the Ancre. . . .

Was it all over and done with; or was it, as Willie had declared, all to do again?

The Ancre flowed in its chalky bed, swift and cold as before, gathering its green duckweed into a heaving coat as of mail and drowning the white flowers of the water-coltsfoot. . . .

A vice seemed to be saying, the voice of the wan star: What you seek is lost forever in ancient sunlight, which arises again as Truth. . . .

So Phillip resolves to return, to be ‘mother and father to the little fellow’. He goes to see his mother and they visit Reynard’s Common, scene of so much happiness in his own childhood days, and he is further helped to come to terms with his present situation. He returns to the Cross Aulton home and we are at last given a clearer picture of these family members: Uncle Joe, Cousins Arthur, May, and Topsy (16 and still at school), while ‘Mrs. Joseph Turney was a homœopathic invalid’.

The idea is being mooted that his sister Doris should take the baby, as she is expecting one of her own. Phillip is not happy with the proposal. Phillip talks to Bob Willoughby who belongs to the Christian Spiritualist Church, and meets his father, a fundamental Salvationist. The seed is being set here, very adroitly, that there is something wrong in Doris’s marriage (as indeed in real life).

So Phillip returns to Malandine and Valerian Cottage. He goes for a walk on the sands, climbs the difficult and dangerous Valkyrie Rock, cleans his cottage: the next day he goes to see his son and finally bonds with him.

Cousin Arthur arrives to stay and the two men go walking across the moors to look for the missing otter – the ‘otter’s odyssey’: eleven days and two hundred miles, ending at Aunt Dora’s cottage in Lynmouth. She is still looking after her two elderly lady ‘babies’. The return involves a hilarious adventurous motorcycle ride – releasing tensions.

But then Arthur tells Phillip that the nursing-home woman has taken legal action against him for defamation – he had told Pole-Cripps that Phillip had said they were responsible for Barley’s death and this has been repeated. Phillip pays up to avoid further unpleasantness. But he now decides to leave Malandine and go and live in Willie’s cottage – Scur Cottage in Speering Folliot (i.e. Skirr Cottage in Georgeham).

For the first two or three days Phillip just sits in a stupor (he actually has influenza). Then Mules the postman, who had known Willie, tells him of the newspaper story that his baby son has won ‘best baby’ prize at the flower show. Mules tells him his wife and daughter Zillah have offered to look after the baby for him. (All this is a clever strategy on HW’s part to clear the South Devon scenario.) The Mules family take him under their wing. Phillip says:

‘I used to look after mules in the army, they were lovely animals, very gentle and hard-working.’

He is contacted by Mary Ogilvie, the girl that Willie had loved, inviting him to her home at Wildernesse.

Part Three: AT THE MULES’

Baby Billy is collected and settled in the Mules’ home. Zillah takes charge. Phillip meets with Mary and her cousin Lucy Coplestone at an otter hunt. It is what is termed a ‘Joint Week’ – a week when various packs combine for the hunt. The next day he meets Lucy again at another meet.

He had discovered by now that she knew all about wild birds and flowers, and liked nothing so much as being out in the woods and fields by herself.

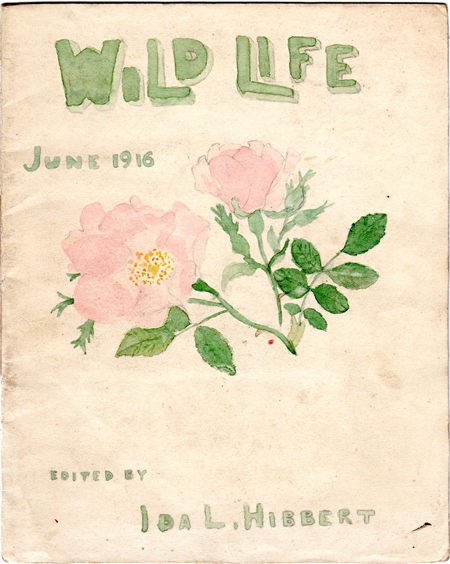

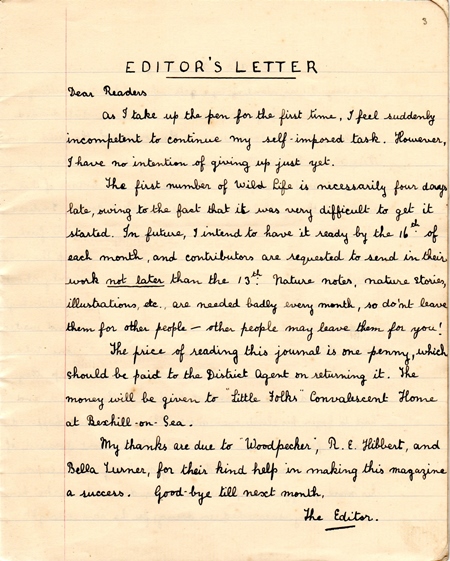

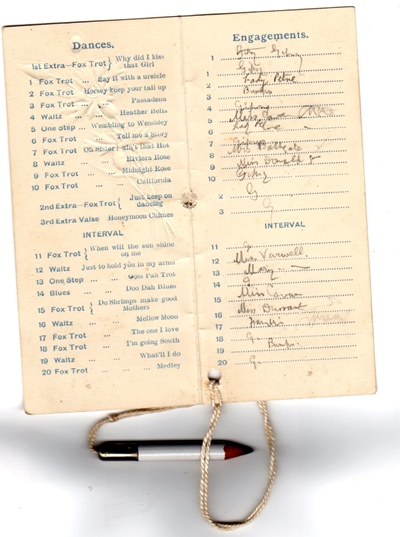

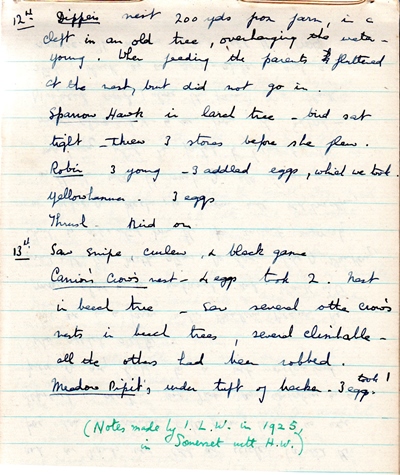

In due course Lucy reveals that ‘I used to write and edit a ‘Nature Magazine’ for the Boys’ (her brothers). Lucy is based on Ida Loetitia Hibbert (known as ‘Gipsy’), whom HW married in May 1925, and they had met exactly as in this novel during the summer of 1924. Gipsy had indeed made a charming little nature magazine, which she both illustrated and wrote in her neat longhand:

|

|

The above is the last page of a short story by the youngest of Gipsy's three brothers, Robin (known as Bin) |

On the penultimate day of Joint Week Phillip (keeping apart from Lucy, who is with elderly relatives) realises that the otter being hunted is his pet otter. The hunt scene here is a reprise of the ‘Last Hunt’ in HW’s best-known book Tarka the Otter – and again a blue libellula dragonfly betrays the creature. But here Phillip jumps into the water, allowing the otter to get away (and in the process breaking every etiquette of hunting; Captain Horton-Wickham does the same in HW’s early short story about an otter hunt).

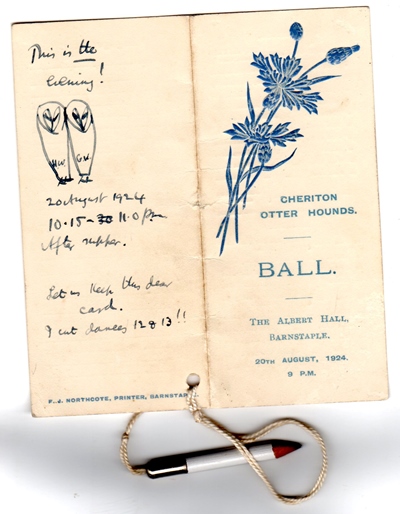

Phillip apologises to the Master (based on William Rogers, Master of the Cheriton Otter Hunt, to whom Tarka the Otter is dedicated), who graciously accepts and indeed invites him to join them in future.

‘The search for Lutra now became the main aim of Phillip’s life.’ He attends every meet for miles around. On one of these he meets up with Martin Beausire last seen in the news office in London before Phillip went walking in the Pyrenees with Rowley Meek and Bevan Swann. Beausire is based on HW’s friend and fellow-writer, S. P. B. Mais. (For further information see Robert Walker, ‘S. P. B. Mais – Henry’s Longest Literary Relationship’, HWSJ 49, September 2013, pp. 35-53.)

We also meet ‘the portly pole-carriers of Sussex’ whom HW lampooned in a cartoon drawing:

We meet Beausire’s parents, and learn about the difficulties with his wife (as in real life). The two men walk on the moor together and discuss authors and their books; among others Phillip asks what Beausire thinks about Dikran Michaelis ‘the Armenian writer’. (This is a little pointer to a small scene that comes later.)

Phillip meets Mary Ogilvie in the village, and it is arranged that he will show Lucy a good camping site for her Girl Guides. Phillip and Lucy go for a walk on the Burrows – as had Willie with Mary in The Pathway – and Phillip wonders if she could take the place of Barley. He signals for a boat to take them across the estuary, and she returns to where she is staying with her Uncle in Bideford. (Gipsy actually lived with her father and brothers at Landcross near Bideford.) On his return Phillip is set down, rather spookily, on the Shrarshook, where Willie had recently drowned.

He now decides to visit Lucy at her home near Shakesbury in Dorset. I find this fictional placing of Lucy’s home a bit of a poser: it is very near the fictional family home of the Maddisons themselves, yet we are not given any sense of this. Perhaps HW thought his readers would never realise their closeness – despite all the clues he cunningly places for us to trace! Phillip meets Lucy’s father and brothers, and all this is as the authentic real life situation, other than the geographical location. He finds everything very happy-go-lucky: ‘Everyone pleases himself here.’

Back at Scur Cottage, we find problems brew with the Mules. They don’t do things exactly as Phillip wants (including boiling and ruining his light cotton breeches), while Zillah has become very possessive about Baby Billy. Martin Beausire and his ‘wife’ Fiona (except that she isn’t – we have been told previously that his wife’s name is Ursula!) arrive for a holiday with a great deal of attached confusion. Beausire complains about everything. They all go for a walk and we realise Beausire knows nothing about ‘nature’ and pumps Phillip for information continually.

The scene switches to the Hunt Ball. Phillip and Lucy are invited to join the Master’s house party. After dinner they drive to the Assembly Rooms. During the evening (after much hesitation) Phillip asks Lucy to marry him and she accepts. This again reflects the situation as in real life.

The next day he takes Lucy to the Mules’ home but they get upset as she does not say good morning to them – being shy; and Phillip has forgotten to actually make formal introductions. So the engagement begins with tension. Later Phillip rushes up to the Guide camp only to find it has finished – so he dashes off to the Coplestone family home in Dorset.

Part Four: DOWN CLOSE

‘Oh, we don’t bother about anything here.’

Saying of Adrian Coplestone, Esquire

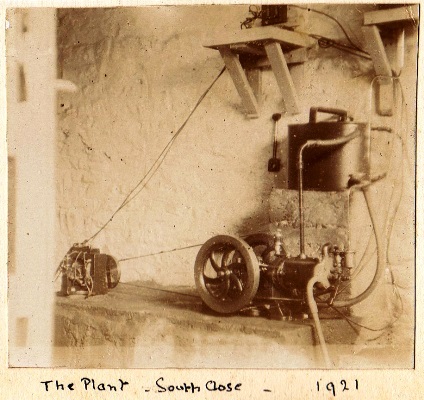

This is a fairly typical remark that would have been made, with the careless confidence of a gentleman, by Charles Hibbert. South Close was the actual name of the Hibbert home at Landcross, and the descriptions of the simple and haphazard life led by the Coplestone family – Pa (as Charles Hibbert was known), Ernest (real life Tom), Fiennes (Frank) and Tim (Robin or ‘Bin’) – are all pretty exact. Gipsy’s mother had died of TB in 1918. Pa had been totally devoted to his wife and had sunk into himself after her death.

The ‘Boys’ had their own engineering business run from a workshop in the garden. They were very skilled but totally unworldly. As in the novel, the real-life situation was a clash of opposites: a kind of hare and tortoise scenario. Neither mind-set could comprehend the other. HW tried to sort them out but had no patience for their attitude and so was continuously in a state of indignant frustration. (One problem was possibly that the still very recent war that had so traumatised him had made no impact whatsoever on this family.)

|

|

A part of The Works from Loetitia Hibbert's photograph album |

On this visit, finding no food in the house (they tended to live on bloater paste sandwiches – again, as in real life!) – Phillip rushes into town to buy paté, pies, sherry, and Dundee cake. He cleans out and distempers the scullery. He also sees Pa’s books with many first editions of natural history. All these details of objects etcetera are exactly from real life, and some of the items are still in existence.

Lucy takes Phillip to meet family friends, Mr and Mrs à Court Smith – ‘Mister’ and his wife. ‘Mister’ has already featured in HW’s writing – he is the gentleman (Arthur Hall) who made the note about the blackbird’s song to be found in The Village Book. These two are very protective of Lucy in lieu of her mother: ‘Lucy comes of a very good family!’ As indeed did Loetitia Hibbert, though the present family, descended via younger sons of younger sons, lived in a penurious state.

|

|

Arthur Hall – 'Mister' from Loetitia Hibbert's photograph album |

Mister insists Phillip speaks to Pa about his ‘intentions’ towards Lucy. Phillip manages, after much hesitation, to ask Pa’s permission for their engagement. He sees momentary fear/shock in Pa’s face, but the old gentleman (born in 1852 he was over 70 at this point) rises to the occasion.

The now officially engaged couple return to Devon, Lucy to stay with her Ogilvie cousins at Wildernesse. They have been invited to spend the night at the home of grander relations, Commander and Mrs Gilbert, at Bideford. They plan to spend the day on the Burrows and cross over the estuary in the afternoon.

It was near the equinox; much rain fell on the Wednesday, opening day of Barnstaple Fair; again on Thursday; but on the Friday, when the highest tide of the year moved into the estuary, the rain had cleared. . . . [ominously] it was the second anniversary of Willie’s death.

Barnstaple Fair was a grand and ancient occasion, held near the equinox. HW describes the event in great detail in ‘The Fair’ in his earlier book The Labouring Life, and Tony Evans gives some historical background to it in Henry Williamson: A Brief Look at his Life and Writings in North Devon in the 1920s and ’30s (HWS, 2001; new edition, revised and reset 2025; e-book 2014).

As they wander hand-in-hand on the sandhills of the Burrows it pours with rain, and in desperation they take shelter in a cattle shippen on the marsh below the sea-wall, making a large fire. Phillip worries that the marsh will flood. It is dark before they do anything about raising a boat to take them over the estuary. They are warned that ‘a big tide is going down, and the wind is rising’. The crossing will be difficult and dangerous: HW keeps the ensuing dramatic description under tight control, creating a very powerful scene (the passage really needs to be read in its entirety to do it justice).

Half an hour later they saw in the near-darkness a salmon boat coming aslant the tide swirling down very fast with the pressure of the combined spate of the Two Rivers. . . . The roaring of the waters leaping seaward was growing louder every moment. . . . The wind was rising with the lessening of rain, blowing strongly from the sea. The boat surged forward against the tide, driving its bows almost under. He saw, with a stab of fear, that they were moving slowly backwards. From behind could be heard the growling of the Hurly-burlies, rocks over which in white undulations, the ebb was leaping. . . . At Point of Crow the boat swung about as its nose pushed into the backwash of the swilling tide. . . . The lights of Instow came nearer. . . . Soon the noise of agitated water arose ahead. This was the String, where the ebb of Taw from Barnstaple clashed directly with the ebb of Torridge from Bideford. The choppy, agitated water, dancing and jerking in darkness, seemed thick to enter. They swung about amidst water leaping in a thousand jets, each with its splashing sound: . . . the noise of the tides in conflict filled Phillip with dread.

Phillip thinks they are to share Willie’s fate, but the fishermen’s experience overcomes the appalling conditions. However, they charge ten shillings instead of the normal one shilling per person. The pair arrive at the Gilbert’s home at midnight to a somewhat cold reception! They are already very unimpressed by the lack of manners of Lucy’s brothers who have recently visited.

They return to Down Close with its innocent (and unworldly) way of life. Lucy now suggests they visit ‘Grannie’, Mrs Chychester, who lives in a cottage in the grounds of what was once her family home which had had to be sold (the location is not stated). Phillip warms to this charming old lady who gives him a treasured ivory paper knife with carved handle.

(‘Grannie’ was Sarah Catherine Augusta Hibbert (wife of Colonel Hibbert) née Lee, daughter of a well-known artist who owned the impressive Broadgate House on the outskirts of Barnstaple; she was the mother of Gipsy’s mother. Due to the foolhardiness of her son and in order to pay his debts, ‘Grannie’ had had to sell the main house. HW always got on very well with her: she was unfailingly understanding and encouraging.)

Phillip has determined to go to London and write the last volume of Willie’s life. He reiterates here the words he has used earlier:

Speak for us, brother; the snows of death are on our brows.

We now find Phillip ensconced in his grandfather’s old house, next door to his parents, at 12 Hillside Road. His mother had sold it, but has bought it back so that her daughters Elizabeth and Doris can come to live there (we learn here that Bob Willoughby is very unstable mentally), to the consternation of Richard Maddison. Phillip tells his mother in confidence that he is to be married again. But the chapter opens with Phillip settling down to write. A few short sentences here describe how HW felt that elusive power overtake him:

It was a thrilling moment; he felt that the breath of creation had come upon him, its servant. . . . he was trusting himself to the spirit of creation, which caused a strange dissolution within. He did not know what he would be writing on the page a moment before it happened. Trusting himself to the imaginative flow, in the secrecy of the empty house, he wrote steadily . . .

HW also mentions being ‘in a state of dream’. That has significance within the writing genre known as ‘dream-narrative’ (discussed in Anne Williamson, ‘Save his own Soul he hath no Star’, HWSJ 39, September 2003, pp. 30-60 – see particularly p. 31). His trance-like state is interrupted by a visit from his previous friend Julian Warbeck, whom we realise is now sadly degenerated.

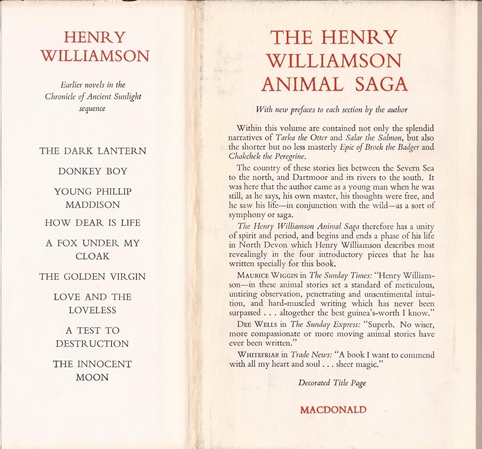

Phillip has also been writing short stories (familiar to readers of HW’s earlier books), but his agent Anders Norse (Andrew Dakers) tells him his stories are not selling: they are too ‘realistic’. On leaving in a rather shocked state, he sees a yellow Rolls-Royce that had once belonged to the legendary sportsman, Lord Londsale: now in the hands of ‘a slim dark man whom he recognised as the famous Armenian writer of romantic stories, Dikran Michaelis’ (as mentioned earlier). They have a drink together. Michaelis shows he is rather bitter:

People despise me, they think of me as the Armenian cad who dodged the war, fakes all his characters, remains ‘every other inch a gentleman’ and whose books are ‘not so much brilliant as brilliantine’.

They both feel they are ‘outsiders’ – and Phillip adds, ‘All artists in England feel they’re outsiders.’

Phillip tells him his work is good. ‘It has feeling and sensitivity.’ But he muses to himself as to why literary critics were so derisive about Michaelis’ writing: ‘His reputation had fallen among beeves: the sharp Armenian goat herded among dull British beeves.’ (‘Beeves’ being the infrequently used plural of ‘beef’!)

Michaelis offers Phillip a lift to Victoria Station, where he is meeting someone off the boat train. Phillip, watching secretly, sees a ‘girl with a calm, self-possessed walk, beautifully dressed . . .’

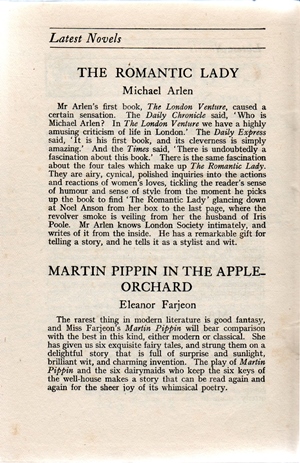

HW must have known this popular and prolific writer, more usually known as Michael Arlen (1895-1956), possibly through the Tomorrow Club. He was born Dikran Kouyoumdjian, and in the 1920s was a well-known society personality who did indeed have a yellow Rolls-Royce, although he was viewed with suspicion by many due to his foreign background. A friend of D. H. Lawrence, he is the basis for the playwright Michaelis in Lawrence’s Lady Chatterley’s Lover (1928). Arlen is known to have had an affair with Nancy Cunard – and no doubt the hint here is that it was her that he was meeting off the boat train. However, it is altogether a slightly curious little cameo to have included. Michael Arlen titles were advertised at the back of some of HW’s early books.

|

|

|

| From the first edition of The Beautiful Years | From the first edition of Dandelion Days |

A letter from Lucy arrives in reply to one he had sent in which he enclosed articles on Arnold Bennett written by his estranged wife. Phillip has likened his own character to that of Bennett. (Arnold Bennett married Marguerite Soulie in Paris in 1907 but they separated in 1921; he had a mistress, the actress Dorothy Cheston, by whom he had a child.) Lucy is not interested in such matters nor understands the hint, which worries Phillip, but he overcomes his doubts and continues writing. But HW has put down a marker that they are not the total soul-mates that Phillip and Barley had been.

Returning to Down Close for Christmas Phillip is met at Shakesbury Station by Lucy and Tim. He has come provided with presents, including a book The Impatience of a Parson by Rev. R. L. (Dick) Sheppard (priest at St Martin-in-the-Fields) for Pa. To his dismay he discovers that Pa ‘has no use for the fellow’ and so gives him a box of cigarettes instead.

Dick Sheppard (1880-1937) was indeed the Anglican priest at St Martin-in-the-Fields at that time. He had worked as chaplain in a military hospital in France during the war until sent home with exhaustion. In 1924 he broadcast the very first service on the BBC. He was also responsible for the now traditional Festival of Remembrance which takes place in the Royal Albert Hall each November. Later, with the Second World War looming, he established the Peace Pledge Union. His book The Impatience of a Parson was published in 1930 – the 1925 book (the date HW is encompassing here) was actually The Human Parson. Sheppard was hugely popular, and he is buried in the cloisters of Canterbury Cathedral, where he had been Dean from 1929-31.

Later –

When the others had gone to bed Phillip walked alone under the stars, thinking of that Christmas night in the wood below Wytschaete, the perforated jam-tins filled with glowing charcoal, the frosty moonlight, the miracle of silence over the battlefield broken only by the distant singing from the German trenches.

Phillip takes over Pa’s library (study) for his own writing:

Among the prints on the walls was one of Pa’s old home, with its lake, deer park, and house of half a hundred rooms.

This was the former Hibbert family home at Chalfont Park in Buckinghamshire, although as one of the family of the younger son of that time, Pa’s parents had only occupied the Lodge.

Tim confides in Phillip about his girlfriend Pansy, who works in a shop in the village. He also reveals the Boys’ detailed and ambitiously expensive plan to expand the Works, to be paid for by an advance on their future inheritance (as in real life: a complicated legal set-up involving Hibbert family money – and this is the ‘rights reversion’ that was to cause a big problem in the future).

Phillip takes Lucy to meet his Uncle John, where he indicates that he would now like to take up the offer to learn to farm the family land at Rookhurst, where Uncle Hilary has bought up Skirr Farm, once belonging to the Temperley family (Willie’s friends of the earlier Flax of Dream series).

The Boys engage a Mr Pidler to build their dream workshop. Problems soon arise. Builder Pidler is pretty much a con-merchant and his work is shoddy and haphazard. The Boys order masses of expensive machinery which arrives before the work is done, and so has to lie around open to the weather and deteriorating. When all is finished (and huge sums spent) no-one comes to buy anything and the one person who wants petrol from the new pumps is turned down!

Phillip recasts several stories and takes them to Anders Norse. He then goes to see his cousin Arthur at the ‘Firm’ off High Holborn, the fictional stationery firm Mallard, Carter & Turney Ltd (actually Drake, Driver & Leaver). He agrees to sell Arthur his Norton for £20 – and decides to buy himself a new model.

At the same time he receives a letter from Anders Norse telling him John MacCourage (John Macrae of Dutton Publishing, USA) wants to publish all his books. He triumphantly buys the new Norton.

|

| Gipsy, HW and his new Norton |

On returning to Devon they have another frustrating visit to the à Court Smiths – where we discover that his wife has bought a rather explicit book on male marital behaviour which she intends to give to Lucy. Mister is not too sure about this: she ‘stared at him with the unwinking stare of a toad about to fix a fly’! Meanwhile, crashing the new Norton on the way home, Phillip shows he is aware of his own selfish extremely egotistical nature.

Part Five: LUCY

‘If I leave all for thee, wilt thou exchange

And be all to me?’

Sonnets from the Portuguese

by Elizabeth Barrett Browning

The poem continues:

Shall I never miss

Home-talk and blessing . . . another home than this?

Elizabeth Barrett Browning (1806-1861) (hereafter EBB), eldest of twelve, was a precocious student and started writing at an early age. When fifteen she suffered a severe spinal injury while out riding. She recovered but in 1838 had a bad haemorrhage. Although recuperating well she had a relapse in 1840, on the death of her mother and two brothers, including Edward to whom she was particularly close. She became virtually an invalid. A volume of poetry in 1844 brought a letter of appreciation from Robert Browning. Their correspondence developed into love after Browning managed to visit her in May 1845. Knowing her very strict possessive father would not give permission, the couple married in secret in September 1846 and left for Italy. A son was born in 1849. In 1850 her Sonnets from the Portuguese were published, written before marriage and so titled to disguise the fact that they were in fact love letters in verse to Robert. EBB died in 1861 (her end hastened by sadness at the death of her sister) and is buried in Florence.

So why is HW quoting from this poem in relation to Lucy? Lucy has no doubts about her situation – it is Phillip who doubts. We have already seen that Phillip knows he is not an easy man to live with and that he has doubts about the absolute suitability of Lucy for his bride. EBB had grave doubts about marrying the poet – her father’s stringent disapproval adding to her own deep hesitations.

The section is entitled ‘Lucy’ and the voice of the poem (Sonnet XXXV) is that of a woman. But Lucy did not have the doubts or troubling thoughts that complicated EBB had. The quotation does not really seem to fit the occasion here – except that the author has made us aware that for Pa (and the Boys) this will be a great loss (as for EBB’s father and family). And indeed, Lucy is leaving all that is familiar and safe for an unknown life. One might feel it is more appropriate to Phillip’s character, thoughts and feelings – but I think HW is being more subtle than that. If he wanted to do that, he would have made it clearer. I think he is laying down a marker to indicate that this marriage is not going to be one that was ‘made in heaven’. There is to be a big question mark hanging over the marriage from the beginning.

Interestingly, this section, though headed ‘Lucy’, continues to be dominated by Phillip! He is immediately seen as still clearing up Down Close – the bath, the closet, the filthy loo – until he receives an urgent message to meet MacCourage in London.

He visits his agent, who hands over a new book by Martin Beausire. When Phillip looks at this later he finds that one of the characters is based on him, and the tale is of Beausire’s earlier visit to Devon. (This is S. P. B. Mais’ Orange Street, published in1926, where the character Brian Stucley is a pastiche of HW.) HW sends the book up a bit here, exaggerating even further Mais’ original tale. MacCourage treats Phillip to a most lavish dinner, and the two men get on well.

Phillip telegraphs Lucy to come up and meet his parents. They like her, but when Phillip tries to ask his father about a marriage settlement (such things still being de rigueur at that time), Richard flares up; although all is well in the end. Richard suggests he invites Uncle Hilary and Aunt Dora to dinner. Afterwards Hilary, with some pomposity, tackles Phillip about the proposed farming project. It is arranged that Phillip will start at Michaelmas. Hilary says he has bought in further land from Tofield:

‘the fellow who bought the land from your grandfather. His only son’s a bit of a waster, I hear.’

This reintroduces a name from the early volumes of A Chronicle of Ancient Sunlight and puts down a small marker which will have considerable import in due course.

The pair return to Devon where they visit ‘Aunt and Uncle Kimmy’ where to Phillip’s chagrin he discovers, having made what he considers a faux pas, that they are actually Lord and Lady Kilmeston (this was Pa’s youngest sister). It has not occurred to Lucy to tell him! Life in their household is stiflingly formal. They move on to other relations at Sidmouth, where Lucy’s cousins are to be bridesmaids: Aunt Dolly (Mrs Matthew Chychester), whose husband we learn had disappeared after having had a spell in prison (these are Mary Alice Hibbert, née Chichester and Lt Col. George Hibbert, and their two daughters – real-life bridesmaids – Mary and Loetitia, known as ‘Tish’).

Phillip leaves Lucy there to be fitted for her wedding dress, collecting her after a few days when they go on to see the Mules and Baby Billy. He goes to see the rector about the banns, only to learn he must produce his birth certificate and proof that he has been baptised, so he rushes back up to London, calling in on the way to see Cousin Arthur, who now refuses to pay over the money owing for the Norton (a true incident that really rankled with HW!).

Going to see Anders Norse to ask him to be his ‘groomsman’, Phillip learns he is with the writer Wallington Christie (John Middleton Murry). This gives rise to an important statement: Phillip’s thought regarding Christie’s article in The New Horizon soon after the war:

‘I shall write the book which Christie foretells: I am that phoenix, and through me my generation shall rise into life again.’

This is reference to the book that would equal Tolstoy’s War and Peace; a point of great importance to HW, and this is (I think) the clearest statement that he makes anywhere that he sees his own writing, his Chronicle of Ancient Sunlight, as fulfilling that premise. (The War and Peace theme is yet to be tackled.)

Catching up with Anders Norse, he finds him talking to: ‘a tall young man with a face of fascinating eagerness.’ Anders introduces him as ‘Roy Inverary’. Phillip says: ‘I have read your great poetry.’ This is Roy Campbell, whose poem graces the title page of this book.

After visiting his parents, where he learns that his father will not be coming to the wedding as he has a board meeting that day, he returns to Down Close, his head full of thoughts about the books he must write, his otter story, his war book and how to go about it, mixed with thoughts about Wallington Christie, and what had that writer meant, and indeed how to achieve what he desperately wants.

Uncle Hilary arrives at the Works unexpectedly in a dark green Delage two-seater, finding signs of decay already overtaking the newly-built workshops. It is Hilary who now questions the plans of the Boys and the cost involved. Phillip tries to defend them, but Hilary warns him not to get involved.

The next day Tim admits to Phillip that is has all cost far more than they had thought it would and that Pidler has diddled them. Fiennes is in charge of accounts but doesn’t tell the others what he does. It is all a huge muddle.

Phillip decides he must finish his book about the otter before he gets married. He shuts himself into his cottage and tries to compose his thoughts (giving the reader some idea of the author’s central purpose, or philosophy – which boils down to the age-old question of ‘good and evil’, a concept which is deeply imbedded throughout the Chronicle).

. . . the source of all life was the Imagination, God was the Image Maker, the species were but images which must pursue their ends to perfect God’s purpose, which was to crate beauty in form, sound, colour, and scent: from the co-ordination of which came the higher love which was above and beyond the personal image.

Opposed to God, or the Image Maker, were forces of destruction, nihilism, darkness, all exploiting the lower feelings by which individual life was maintained, but if not transmuted into greater love . . . would frustrate the purpose of the image Maker.

He writes 50,000 words over three days and nights. Suddenly Zillah reminds him that his wedding is in three days’ time and he has done nothing about a top hat! He panics. The cottage has to be cleared, cleaned and renovated from top to bottom. He gets a huge bonfire going to the consternation of neighbours. Eventually Zillah and her mother take over. In the middle of everything his mother’s wedding present arrives: a huge dumpy and totally unsuitable armchair.

Eventually all the tasks get more or less finished in a race against the clock. His wedding togs arrive and seem OK – apart from the overlarge top-hat! Anders arrives and is calm and helpful. (HW’s actual best man was Richard de la Mare.) There are quite a number of guests at the wedding, including the Master of the Otter Hunt.

The ceremony is described with due reverence and sympathetic thought for the feelings of Lucy’s father, whose dead wife lies buried in an unmarked grave outside. Phillip feels Barley to be present, and a swallow flies around inside the church as they leave, Lucy’s Girl Guides forming a guard of honour.

As they leave it starts to pour with rain. The complicated arrangements involve leaving in a hired car which is to stop just down the road and drop them off, to await the arrival of Tim in the Trojan who is going to drive them to Exmoor after dropping off Anders at the station, and then returning for Phillip’s mother and sister. It is all somewhat chaotic and upsets Phillip’s already raw nerves.

The drive to Exmoor is fraught with the storm and the mechanical problems of the Trojan. Eventually they arrive at their destination, a farmhouse down a remote track, where they are given an inadequate supper. The wedding night is a disaster as the groom tries to force himself on his innocent bride, but the next day they walk on Exmoor looking for nests of the ‘water-colley’ (dippers). In real life, Gipsy made some nature notes about their walks:

They spend several happy days exploring the many water courses in the area, and the reader hears of life on that remote farm. On the last afternoon they walk to Oare, setting of Lorna Doone, then Fiennes and Tim arrive in the Trojan to take them back to Down Close, where in the interim they have fitted a side-car to the Norton. The plan is now to go over to France to the battlefields. They collect Billy and set off.

En route, they call on the Beausires and then continue on to Hastings and beyond to Winchelsea where Phillip hears a nightingale:

. . . as clearly as though the bird were in the room. It was singing in the garden immediately below. In the pause of the deep throbbing notes, tereu, tereu, tereu, another answered in the distance, and soon a third had joined in the singing, and a fourth far away across the fields. He thought of Keats, of Stravinsky nights in the Doves’ Nest above the gallery at Covent Garden; he thought of the poem Heraclitus in The Oxford Book of English Verse, he thought of Willie, and the spring nights of the vanished world while the guns were flashing and ‘thy nightingales awake’ in the valley of Croiselles before the Hindenburg Line; he thought of ‘Spectre’ West; and of other faces in that hopeful June before the Somme; and it seemed as though his heart had opened to all life through the friends he had known in the war.

Lucy now comes to him naked, with her long black hair loose, and taking his hand, leads him to the bed. The whole tone changes in these final paragraphs. The next day they walk on Romney Marsh, delaying going to Folkestone and on to France. Phillip suddenly announces that he wants to go home. They decide to go to Rookhurst and to camp there until Midsummer, while he begins to learn how to farm. The final scene shows this new family, Phillip, Lucy and baby Billy in one embrace.

*************************

Index to It was the Nightingale

Between 2000 and 2002 Peter Lewis, a longstanding and dedicated member of The Henry Williamson Society, researched and prepared indices of the individual books in the Chronicle of Ancient Sunlight series (the first three volumes being indexed together). Originally typed by hand, copies were given only to a select few. His index to It was the Nightingale is reproduced here in non-searchable PDF format, with his kind permission. It forms a valuable and, indeed, unique resource. The synopsis (with Peter Lewis's delightfully idiosyncratic asides) is not included, as essentially it repeats information already given in the consideration above.

*************************

Click on link to go to Critical Reception.

*************************

The dust wrapper of the first edition, Macdonald, 1962, designed by James Broom Lynne:

Other editions:

|

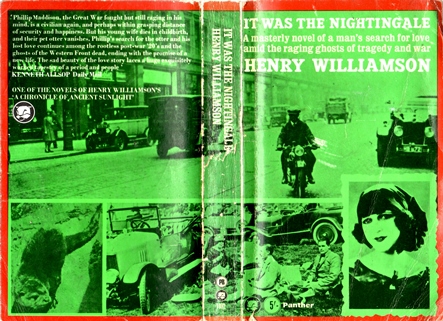

|

Panther, paperback, 1965, with a wrap-round cover montage of appropriate period photographs |

|

|

|

| Macdonald, hardback, 1985 | Sutton, paperback, 1998 |

*************************

Back to 'A Life's Work' Back to 'The Innocent Moon' Forward to 'The Power of the Dead'