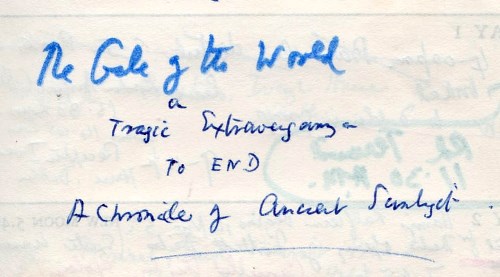

THE GALE OF THE WORLD

(Vol. 15, A Chronicle of Ancient Sunlight)

|

|

| First edition, Macdonald, 1969 | |

Photographic essay (HW's photos of the Lynmouth Flood Disaster, and others)

First published Macdonald, 1969 (30/-)

(The first printing of 3000 copies in February 1969 was withdrawn due to multiple printing errors; the second printing of 6000 copies was published on 29 May 1969)

Macdonald reprint, 1985

Sutton Publishing, paperback, 1999

Dedicated:

To Kenneth Allsop

Kenneth Allsop (1920‒1973) had first approached HW sometime in 1935 when he cycled to Shallowford (then the Williamson family home at Filleigh, North Devon), expecting attention from his hero, the great writer. HW was in a state of considerable tension at that time, coming to terms with the recent deaths of both Victor Yeates and T. E. Lawrence, combined with the pressing need to finish Salar the Salmon. He fobbed off the rather brash young lad on to his son Bill (Windles); aged 15, young Allsop was not amused!

In 1948 HW heard from Allsop again. He had briefly been a reporter before the Second World War but had joined the RAF as a pilot in 1940. He was invalided out of the service due to a tubercular knee, and his leg had to be amputated. Now, he had just finished his first book and asked HW for help in getting it published. HW contacted his publisher, who turned it down, but Adventure Lit Their Star (the story of little ring plovers nesting on Tring Reservoir) was subsequently published by Latimer House to critical acclaim, winning the John Llewellyn Memorial Prize.

Allsop rose to fame as a journalist, writer, and broadcast interviewer, with a reputation for being acerbic and hard-hitting. He and HW had a quite close relationship, but Ken unfortunately ascribed the MC to HW in a review of The Golden Virgin in 1957 (in which Phillip is awarded this honour). HW was devastated by this mistake, for he thought that people – his friends, acquaintances and his readers – would assume that he had made this claim, and think him to be a liar and a bounder. Ken made no public apology, and this caused a rift between them. A further problem was caused later when Ken interviewed HW on television and unexpectedly asked probing personal questions. HW parried him successfully, but later noted that he thought it had all been 'rather near the knuckle'.

In February 1968 Allsop invited HW to attend his inauguration as Rector of Edinburgh University. No doubt it would have been at that point that HW decided to dedicate this final volume to him. Allsop apparently did not like the book, however, for he did not review it; or perhaps he felt that as its dedicatee it was not his place to do so.

Allsop was often in pain from his leg, although he did not let this hinder his penchant for driving fast cars. He killed himself in May 1973. HW had seen him only a couple of weeks previously as both had attended a meeting of the West Country Writers’ Association. HW gave the address at his funeral.

*************************

The Gale of the World, the fifteenth and final volume of A Chronicle of Ancient Sunlight, is fittingly both climacteric and climactic.

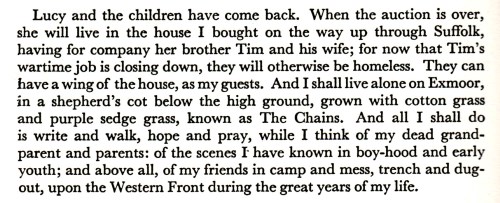

At the close of the previous volume, Lucifer before Sunrise, with the Second World War ended, Phillip Maddison, in a state of suppressed desperation, has sold the Norfolk Farm. His wife and children were going to live in the new house in Suffolk:

(This followed the overall outline of the Williamson family in real life.)

So Lucifer before Sunrise ends on a note of seemingly calm resignation: but within that calmness there is surely an underlying feeling of desperate uncertainty ‒ what lies ahead?

What lay ahead is now revealed in all its complicated catastrophe, giving a truly dramatic end to this superb series relating the life of an ordinary – yet unusual – family in the first half of the twentieth century through the life of Phillip Maddison, based to a large extent (but not totally) on the life of HW himself.

There are so many threads drawn together within this final novel, and so many strange scenarios presented within the plot, that the reader can feel an overwhelming confusion. But once the essentials are grasped the complexities dissolve into clearer pattern, and as the looming sense of doom resolves itself by coming full circle, creating a perfect whole, we are left with a powerful sense of satisfaction that all has ended well.

Set in the uncertain and complicated aftermath of the Second World War, the novel sets out an overall socio-historical context which reflects the turmoil of thought and action of that time, portrayed in various ways by Phillip and his friends and acquaintances. However, Phillip moves through the created exigencies almost in a dream. He doesn't really participate. He is crushed and withdrawn, lost in his own problems and nightmares (indeed the whole book can be seen as a feverish nightmare – an allegory of the all-too-recent Armageddon of the Second World War), all of which seem unresolvable until the catharsis of total devastation releases him from his lethargy and he is 'Free' – free to begin his life's work. The allegory of debilitating blindness which dogs him throughout this novel disappears: Phillip can, in every sense, see his way forward.

The overall theme or message woven into The Gale of the World is one of tolerance, forgiveness, compassion, reconciliation, and hope: there is at the end a metaphorical rainbow which, although it does not literally appear, is nonetheless as obviously apparent as that following the Biblical catastrophe of Noah's flood, and the new beginning indicated after the annihilation of Wagner's Götterdämmerung, the climax of the Ring cycle, which signified the ending of the old order – the gods who had become contaminated by evil deposed – when after fire, a devastating flood arose to cleanse the world and start anew. The Second World War – the 'fire' – did depose the evil order. And HW uses the 1952 Lynmouth flood disaster allegorically to cleanse Phillip's world. Europe had an opportunity to start again. Phillip Maddison starts again — and HW himself was starting again.

As the book opens, we find Phillip Maddison has returned to Devon and is living on his own in a 'shepherd's cot' situated on the northern side of Exmoor above Lynton and Lynmouth, and just below that high wild area known as The Chains, a place of great importance in HW's psyche. He is in a disturbed state of mind that reflects the disturbed state of Europe at the end of the war (which, for HW, echoed the problems that arose at the end of the First World War, when the punitive Versailles Treaty alienated the Germans as a nation, and which HW firmly believed led to the conditions initiating the Second World War).

His unease is also due to the fact that he is convinced he is going blind and will no longer be able to write. If this does happen then he plans to build a huge pyre upon The Chains and immolate himself upon it. His sister Elizabeth (with whom he has never got on) is also living in Lynmouth in 'Ionian Cottage', which she has inherited, by somewhat devious means, from their Aunt Dora.

Also gathered in the vicinity are a large supporting cast of characters, some of whom are familiar from previous volumes, while others are newcomers to the story. Each 'faction' brings its own set of complex thoughts and often seemingly bizarre actions. Only 'seemingly bizarre', because strange and fantastical though they may appear to be – nearly all the incidents that occur are based on people and events that really happened, as will be explained in due course.

There are readers who find the inclusion of the politics of the era an unwonted intrusion, even though they are actually a very small part of the total plot. But this was a fact of life of that time – a part of the social history of this country. It should not be ignored or airbrushed out of history. HW was very concerned that the aftermath of the Second World War would result in the same problems that had arisen at the end of the First. He thought that Mosley's book The Alternative suggested a solution, a way forward, its main message being that a United Europe was the key to the future: and indeed in due course that did come to pass. (Although recent events have undone that bond.)

But first and foremost, The Gale of the World, incredibly rich in detailed description of the landscape and the moods of mature, is a celebration of Exmoor. It is a wonderful evocation of the feelings, memories, and energies that emanate from the area and from that era. Devices such as the 'séance' calling up spirits from the past (Shelley, Francis Thompson) and including a character from a previous unrelated book (The Gold Falcon), thus bringing that book’s theme to the fore, allows HW to widen the atmosphere of 'Romanticism' that pervades this volume. We find the behaviour of various individuals reveals not just a release from the tensions of the war years, but also an attempt to understand the meaning of life. Thus in many ways this volume relates to his earlier The Star-born, which in its turn related directly to his thoughts arising from the First World War as expressed in his (unpublished) 1920s 'Richard Jefferies Journal'. There is also a distinctive reminiscence of, and allusion to, The Tempest and A Midsummer Night's Dream intertwined throughout the plot. Both these Shakespearian plays come within the 'dream-narrative' genre that had its roots in Chaucer and French romaunce literature. (For discussion of this aspect of HW's work, see Anne Williamson, 'Save his own soul he hath no star', HWSJ 39, September 2003, pp 30-59.)

The most significant theme threaded throughout The Gale of the World is that of Francis Thompson and Percy Bysshe Shelley, and the ethos that surrounded them: an ethos of Romantic mysticism encompassing Thompson's phrase 'All things linkèd are' – making the book an acme of Romanticism in its fullest sense, with nature and the sense of another world (the chief ingredients of Romanticism) intertwined throughout the plot. This embodiment of Romanticism is further embedded with ideas of Keats and William Blake. The text is imbued with references to their work and lives and philosophy.

Shelley had lived in Lynmouth for a short while in 1812, and HW weaves this into a central pivot of his tale. While there Shelley wrote his famous 'Declaration of Rights . . .', putting copies into bottles, launching them in the sea, and sending them off on his own patent home-made air balloons across the sea to Wales. (He then had to flee precipitously as 'Authority' planned to arrest him.) One of his chief pleasures was in making little paper boats and sailing them down streams, and HW uses this to great effect within his own story. That Shelley drowned in a storm off Spezia in Italy in 1822 is also a chilling forerunner to HW's own ending of this book.

HW uses Francis Thompson's poem written in homage to mark Shelley's death as a further fulcrum to his plot. HW had a copy of Thompson's poetry with him in the trenches in the First World War – the 'Great War' of HW's generation – in a volume given to him by his Aunt Mary Leopoldina (Dora Maddison in the Chronicle of Ancient Sunlight novels, who dies in this volume). But in his archive there is also an evidently precious page about this extraordinary poet, kept from a 1913 copy of T.P.'s Weekly, proving an even earlier interest. It is obvious that he also read Thompson's essay on Shelley at an early stage in his life. At the time of writing The Gale of the World HW had become the President of the Francis Thompson Society and had written two major essays on his work. (For further information see the entry for Francis Thompson.) It is most noticeable that very early in the book Phillip says:

'I think I must be like Francis Thompson - “I am an icicle whose thawing is its dying”.'

The spirit of Richard Jefferies is also intrinsic within HW's tale. The very essence of 'Ancient Sunlight' and the spirit of The Story of My Heart, with its theme of the historic significance of tumuli and that sense of an unseen world, resides in HW's use of The Chains of Exmoor with its ancient tumuli that loom over the entire book, reflecting Jefferies' philosophy and spiritual belief in nature and eternity. HW states, through the words of Miranda:

'But to become whole one must pass through nature fully aware, then one can perceive an aspect of eternity, as Richard Jefferies did in The Story of My Heart.'

And so the last sentence of this final volume reflects HW's whole raison d'être – his purpose intended – and, finally, achieved:

'O my friends! My friends in ancient sunlight!'

(Details relating to these points will become clear within the book commentary.)

*************************

The birth of this final volume of A Chronicle of Ancient Sunlight was long and difficult. It was to be the climax of his life's work and HW worked hard to get the effect he wanted.

There is very little archival evidence to reveal how HW decided on the actual subject and content of this final volume of the Chronicle, but there are various circumstances within real life that were very obvious catalysts. As stated, most of the events that occur within the structure of the book actually happened. However, whereas in real life they were spread out over a number of years and not all in the same place, here in the novel they are almost contiguous and occur within a compressed time-scale of about one year. This concentration gives a tremendous intensity to the plot and action.

We know that the Chronicle itself had been envisaged from HW's earliest writing years, and that it had grown from his original concept of covering the years of the First World War, not just once he had actually begun to write it, but well before, and particularly after he had moved to Norfolk to farm, followed by the advent of the Second World War. Those major events in his own life and in that of the world extended his structural scope, but (to state the obvious) could not have been envisaged at the early stages. When he actually began the writing in 1947‒48, his intention was that the Norfolk Farm era should be the pivotal and opening point, from which he would then move backwards and forwards in time. Luckily he was dissuaded from that path (and it is one of the few occasions he actually listened to advice and acted accordingly!).

But now with the Second World War ended, the Norfolk Farm sold, his marriage ending in divorce, HW returned alone to the haven of Devon – as at the end of the First World War and in a similar state of mental breakdown – and in due course finally began to write the first volume of this long-intended series, The Dark Lantern.

This last volume opens more or less at that point of his return to Devon, but there are major differences from HW's real life within the novel which will become obvious. A short recap of HW's actual life at this time is therefore perhaps useful, to set the background and to show how masterly he structured this final volume of the Chronicle.

When HW first returned to Georgeham in October 1946 he stayed for a short while with his friends Mike and Margery Mitchell, who at that time lived in the village while tending a smallholding on land between HW's Field at Ox's Cross and the woods of nearby Spreacombe (the modern spelling; variously Spreycombe and Spraecombe). At this point HW fell precipitously in love with Susan Connely, the sixteen-year-old step-daughter of his friend Malcolm Elwin, who was married to Eve Connely and living by courtesy of a friend at Underborough at Westward Ho!. (It was Elwin who was the key to the Chronicle being published by Macdonald.) That potential 'Barleybright' relationship was, however, terminated very firmly by the Elwins (mainly by Eve) to HW's inevitable anguish. Susan plays an important role in The Gale of the World, as will become apparent.

Negley Farson, the American journalist, writer, and renowned fisherman, also has a role in this novel as Osgood Nilsson. Negley had come to live in one of the small number of white houses that are found under the cliff above Putsborough Sands, immediately below HW's Field at Ox's Cross. HW and Negley had a fairly tempestuous relationship, mainly due to Negley's problem with alcoholism.

HW has lifted this entire local scenario quite literally (and literarily) and placed it, very cleverly, in Lynmouth and the surrounding area.

This was also the era of HW's involvement with The Adelphi magazine, and that too features in the novel. So too does the Alvis Silver Eagle, for it is the Alvis that Phillip is driving in this novel, still of course modified with its box body from its previous use on the Norfolk Farm. Not so in real life, for HW had bought a 1938 Aston Martin sports car, registration DYY 764, earlier in 1946 while still living at Botesdale (emulating the famous Aston Martin racing driver, Jock Horsfall, who lived nearby), and on the day he returned to Devon had given away his Silver Eagle, DR 6084, to Ann Welch (née Edmonds), his original 'Barleybright' romance of the 1930s. (She, now a keen glider pilot, used it to retrieve tow ropes after gliders had been launched. Miraculously, now restored and cossetted, the car has survived the years.)

In the summer of 1948, now living back in the Field at Ox's Cross, HW met Christine Duffield, whom he married in April 1949 (after an earlier plan for a January wedding had been wrecked by her mother). Christine does not feature in The Gale of the World, although HW does introduce other instances and characters (notably one particularly tumultuous affair) from his later years.

HW had already begun work on the Chronicle some time before his second marriage in April 1948 – particularly concentrating first on the farm era, but (with initial reluctance) soon turning to that very early point of the Maddison family life with which we are so familiar. That first volume, The Dark Lantern, was published in November 1951. That date is important, for at the very end of that volume the two Maddison brothers, John and Richard, together with Richard's wife Hetty and their baby son Phillip and John's wife Jenny, take a holiday with spinster Aunt Theodora ('Dora') Maddison at her cottage in Lynmouth on the North Devon coast. It makes an idyllic episode.

That HW should have decided, at such an early point in the series, on Lynmouth as the setting for that holiday seems almost prescient. Volume 2, Donkey Boy, was already at the printers when, over 14/15 August 1952 there occurred the violent storm over Exmoor that caused utter devastation to Lynmouth as flood water poured down the East and West branches of the River Lyn, sweeping away all before it and killing several people. And it is that storm that HW uses for the climax of this book and the whole series.

The day following the storm HW drove over Exmoor (apparently bluffing his way through the police cordon as 'Press', though actually the policeman on duty knew him) to see the damage for himself. He spent some time there and took a small number of photographs (these are reproduced in the Photographic essay). His diary entries are very sparse, but he would have recorded every detail in his mind's eye:

Surely it was then, while actually there at the site of the disaster and realising the dramatic potential, that he would have seen the whole event in terms of a finale to his series. Indeed there are a few notes written into his diary on 18 August that unusually do not really seem to apply to anything – they are just oddments of thought, but which include the phrases:

Rains. Evening on The Chains. … Fox look in hut at night. . . . Lynmouth. “Evil-smelling mud” – “Burst its banks”.

In 1952 the writing of that climactic scene was still a long way off – over ten years off, in fact.

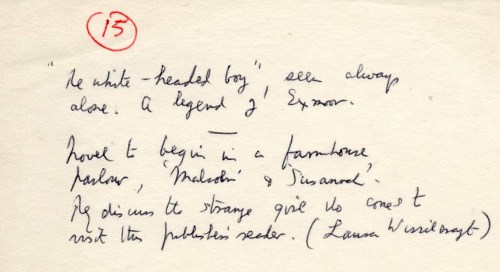

Many further early notes exist, undated, such as:

In mid-November 1963 HW was living alone in his cottage in Ilfracombe, Christine having left him at Christmas 1962 for John Fursdon, the son of HW's platoon officer in the London Rifle Brigade front line trench in December 1914. He was a friend, which made the whole business a double betrayal. Staying with HW, ostensibly as his secretary, was Kerstin Lewes (later Hegarty), the half-Swedish girl with whom he briefly thought he might find solace, but Kerstin was wrapped in her own problems.

On 18 November, HW, depressed and morose, decided during a raging winter storm to walk on Dartmoor, leaving late at night. He actually went first as far as his Writing Hut in the Field above Georgeham and slept there. But he got up at 3 a.m. and made an entry in his diary that reveals the turmoil of his mind – his depression over Christine's desertion being foremost. He determined that if he came through the ordeal he had set himself, he would have conquered his death-feeling:

And now for the journey, which I hope will give me a sense of reality for the climax of my A.S. series, in the night of the storm when Lynmouth was washed away.

He then drove down to Okehampton on the north side of Dartmoor, to walk from Belstone through the wind and driving rain, recording:

I got through, great winds, rain, heavy ascents on springing legs, clad in nylon mackintosh under German 1944 cape, with otter staff. The Taw and Okement dangerous white foaming and very swift and deep rushing rivers. Returned at 2 p.m. to Belstone & fled to Ilfracombe to find K. had cleaned house.

So this is November 1963. In the context of the Chronicle volumes, volume 11, The Power of the Dead, had been published the previous month (October 1963). HW was already working on not just the next volume, but sorting out the huge mass of material already written on the farm years (which he had at last got to!) which was to be volume 14, Lucifer before Sunrise, published in 1967. And concurrently with all this, as early as 1963, he is also working on this final volume!

Further, the day after this Dartmoor adventure, HW noted that he went up to the Field on his own and, quite extraordinarily, got out the typescript (so, already written) of 'the pigeon book': that is, The Scandaroon – not actually published until 1972. That there is evidence of work on these later volumes at this early stage is of great interest in researching HW as 'writer', and an indication of the tremendous work-load and consequent strain that he was under.

On 13 February 1964 he met the very intense and temperamental writer Ann Quin, and from then on they became involved in a short-lived but turbulent affaire. Noted for her experimental style, she had already had her first novel, Berg, accepted by Calder, and HW recognised her talent, though it was one quite alien to his own. In May 1964 he wrote to Father Brocard Sewell, commenting on Berg that: 'At the end of this morality play, decorated by the familiar and nowadays fairly innocent four-letter words (as indeed used now and again in private living), it all begins over again: the characters are as they were. Grace had not yet come . . . Superficially, Berg is a sordid story. But it more than repays study. Beneath the "illusion" of its reality one perceives a talent of rarity and grace.' (HW reviewed the book in The Aylsford Review, Summer/Autumn 1964.) Quin encouraged HW, while he was at the earliest stages of drafting The Gale of the World, to write scenes in the same vein, but these passages made uncomfortable reading, and I was later able to persuade him to delete them. Quin, years after their relationship ended, suffered bouts of mental illness and in 1973 walked into the sea at Brighton and drowned herself. HW portrays her as 'Laura Wissilcraft' in The Gale of the World.

|

| Ann Quin |

A note HW made about Berg, that he later annoted as being for no. 15 (i.e. The Gale of the World):

There is then a gap of nearly two years before there is further mention of The Gale of the World in his personal papers. The first indication occurs in a postcard to Fr Brocard Sewell in February 1966. This mainly concerns the essay on Francis Thompson that HW was writing for the new limited edition of The Mistress of Vision to be published by St Albert's Press under Fr Brocard's editorship. HW added a PS to the card:

Am almost start [sic] final novel. Quaking. Overborne by so much material, notes, etc etc gathered through the years. So may not be able to tear myself away on 18 March for Aylesford.

(At the same time a new edition of The Hound of Heaven was being prepared by the Francis Thompson Society – with another essay by HW.)

Again in early March, HW indicated to Fr Brocard that he could not spend too much time on an essay on Thompson, as 'I must concentrate on my novel now – or perish.' As a PS to a further letter to him in April, he adds:

In the summer of 1966, with volume 13, A Solitary War, safely with the publisher, and with the main writing workload concentrated on volume 14, Lucifer before Sunrise, there is an interesting diary entry on 11 August:

I told Robert [one of his sons, then staying at the Field doing maintenance work] all the plot and sequences of the final novel today, as it appeared before me. [Whether in a dream or as thought processes is not clarified.] Then hut repairs – cement, key for plaster etc cut across the 'dream' - & later I forgot everything – my own 'man from Porlock'.

(This is a reference to Coleridge, and the interruption to his opium-vision of Kubla Khan by a visitor from Porlock.)

A Solitary War was published in September 1966. HW had now finished Lucifer before Sunrise and was undertaking final revisions before handing it over to Macdonald on 25 January 1967. He was then in London, and intriguingly his diary entry for 23 January 1967 states:

Revising / reading TSS of 15 at Nat. Lib. Club. [National Liberal Club]

14 February: Writing No. 15 well.

15 February: Writing going well.

16 February: 15 well. Have finished Chapter 9 of Part Two. 'Summer in new land'.

(That does not appear in the published book – 'Summer in Another Land' becomes the title of Part III.)

On 29 February he made rough notes for a new beginning, in the back of an old copy of The Aylesford Review:

On 21 March the awkward TV interview with Ken Allsop was broadcast. HW took it quite well, although noting he felt the questions were 'rather near the knuckle'. However he had several letters from friends who were furious on his behalf.

In April HW noted that Margot Renshaw (now Margot Wall, her married name since 1945 – 'Melissa' of the novels) was at East Grinstead in Sussex. She was on 'sabbatical' from her home in South Africa, studying Scientology under Ron Hubbard, whose English headquarters was at East Grinstead. All of which duly gets written into The Gale of the World – but removed to North Devon.

(Scientology is the quasi-religious-psychological sect founded by the rather dubious Ron Hubbard. See Anne Williamson, 'Rise and Shine III: A Rainbow Follows the Storm: Some Thoughts on The Gale of the World’, HWSJ 49, September 2013, Note 28 on p. 25. For those interested in more, Wikipedia devotes a long entry, equating to 37 printed pages, to Hubbard, in an excellent analysis.)

On 2 August 1967 HW learned of the death of Siegfried Sassoon, and was asked to comment on this great man by the Evening Standard. Two weeks later he was staying with us (near Chichester in West Sussex). Margot came down by train from nearby East Grinstead for the weekend. On 18 September they returned together to Devon (the Renshaw family home being at Instow on the Taw/Torridge estuary), and HW noted that he was spending a great deal of time with her. But that his mind was concentrating on The Gale of the World is shown by the 'Notes' page opposite the week for 18-23 September, where he wrote:

Margot left Devon on 28 September for London and then on back home to Natal. The next day, HW noted:

Began revising & familiarising myself with No. 15 again. Margot had much to say about my condition (psychic) & psychological after her long swotting of Ron Hubbard's Scientology.

Sunday, 1 October: Gerry Russell came to tea in the hut. I read parts of 15. She asked me to remove Gurkha who 'slashed' Melissa's cheeks in India. Said such fine men. I obeyed. (It was Gerry Russell who was slashed as a fact, in conditions as described in my novel, less Laura W.)

(This reference, somewhat obscure here, will be explained in my consideration of the book.)

On 17 October he noted: 'DIVORCE from CMW – decree nisi granted.'

And it was around this time that he had the first contact with the young lady self-named 'MUS', at that time a student at Exeter University. Being in a vulnerable state, inevitably he fell for her, leading to a relationship fraught with her ambiguous vacillations in the months and indeed years ahead.

Lucifer before Sunrise was published on 26 October 1967. On the 'Notes' page opposite this entry he recorded:

Life was hectic for HW at this time, frenetically rushing around seeing people, and with interviews, talks, parties, etc. The next mention of The Gale of the World is on Wednesday, 27 December:

I wrote all day, & to 2.15 AM Thursday on Part 4 of Gale, 15.

At the beginning of 1968 he noted that he was disappointed with the reception of Lucifer before Sunrise and is worried that The Gale of the World will be a fiasco. January saw a period of intense work on the book. On 1 January he noted he was nearing the end of this final novel:

Writing & recasting Part IV (St. Elmo's Fire) of what will be my last novel.

But he was fretting over the lack of letters from MUS and feeling depressed, unable to stir himself:

One is chronically weary, & the constant change over from the unseen world of the Imagination to the 'real' world – need to buy food, cook, etc etc etc produces this dilemma . . .

7 January 1968: I went to Lynmouth to look at the Barbrook area for the flood climax of 15. And on down the valley road to site of caravans (Lucy among them) which was flooded on the Fri/Sat night of August 15, 1953 [sic – it was 1952].

The next day he recorded how cold it was in 4 Capstone Place, where he was: 'trying to write all the time, as for a year past . . .'

11 January 1968:

In his appointments diary in 'Notes' opposite 22 January he recorded:

15 Note. In ultimate chapter, Mornington & telephone calls – he has one from Casper Field & Phillip speaks, C.F. says Melissa in Ionian Cottage. This determines Ph. to get to her & Elizabeth, by canoe (later).

(Again, this will be clarified in due course.)

On 26 January his main diary records:

I motored to Liskeard, Cornwall, to collect some revised chapters of Gale. The Cummins most hospitable. I was made welcome & happy. [Liz Cummins – his secretarial typist.]

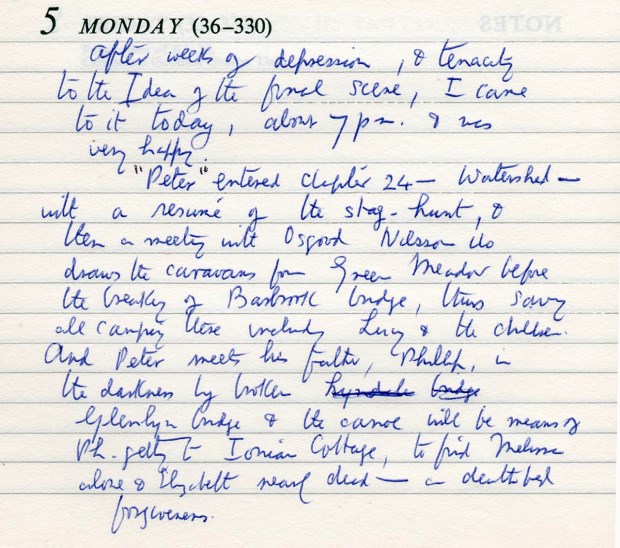

5 February 1968:

On 11 February 1968 HW recorded, with considerable emotion, in both diaries:

Appointment diary:

I finished the FINAL novel of the Chronicle at 4.20 pm this day & staggered about the cottage, tears streaming, & almost incoherent to myself – a surprise reaction! Tho' I fancy it happened after The Pathway – in which case The Gale will go well & at once when published!

The main diary records:

Transcript:

At 4.20 pm today I finished the Chronicle and got up, suddenly broken, from the table – or hysterical is a better word – my eyes streaming & my voice uttering lament, at the strangeness of physical disassociation. It felt like being suddenly born – or borne away from an old existence. I walked from empty room to empty room of this Ilfracombe cottage, crying 'It is finished – O my God, I have come to the end – ', then I sat down by my wood fire & remained still; before going upstairs to telephone in turn a) Margaret b) Richard c) Robert.

(The configuration of the narrow Ilfracombe cottage, which was on a steep slope, with a street entrance at both front and back, was such that there was basically one room on each floor – the kitchen was at the bottom or basement, depending on which entrance one used! 'Upstairs' was a sitting room and a landing with small hall, with bedrooms above. Books and boxes were stacked everywhere, especially on the stairs.)

That scene and those thoughts were incorporated into the poignant 'L'Envoi' at the end of the published book.

One week after those emotional entries in his diary HW noted:

On 1 March he visited Liz Cummins at Liskeard: in one diary he states he collected the final typescript – in the other that he took it to be typed! No doubt he was still revising and honing his text.

On 6 March he gave a talk to students at Exeter University, organised by MUS. His relationship with this young lady was to plague him with alternate ecstasy and extreme anguish for several years, as she kept him on a string for her own convenience.

On 9 March he noted, having been to Exeter to see MUS, that on the way back he stopped at the Fox and Hounds (a favourite local) where he ‘saw dear old (Steenbeke 1917) field gunner – Brigadier Ferguson – ' (I have not been able to find further information about Brigadier Ferguson.)

On 20 April HW made a visit to Lee Abbey (seemingly to attend a meeting of the Devonshire Association, of which he was a member). Lee Abbey is on the North Devon coast just beyond the wild Byronic Valley of Rocks – which features strongly in The Gale of the World, as will be seen. While there he took a friend 'to view The Chains to get detail'. He was still working on the finer points of the book.

Then, on 24 April he recorded: 'Posted revised sheets of Gale to Macdonald.'

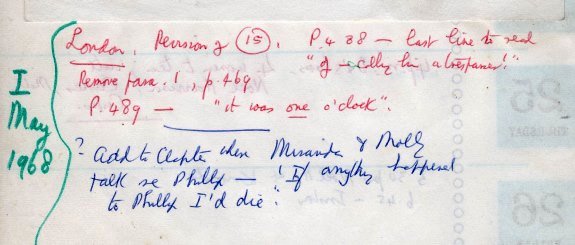

At the beginning of May he was in London – mainly sitting for the sculpture of his head by Anthony Gray. On 1 May he noted he had attended a Dinner at the Royal Academy, and earlier collected the typescript of '15' from 2 Portman Street (Macdonald’s offices). The diary Notes section for this day reveals yet further changes to be made:

HW returned to Ilfracombe on 4 May. The following day:

Alex came with the carbon copy of 15 she had read. I went through my copy (from London) with all of James MacGibbon's queries & proposed cuts. He wants all reference to 2nd World War omitted! The egg without the yolk!

(Alex is Alexandra Penniall, his current typist, living in Ilfracombe and working for HW seemingly since early March. MacGibbon was one of Macdonald’s editorial staff.)

6 May 1968: Alex and I went through the version I cut in places yesterday: & settled the final form of The Gale of the World.

11 May: I posted 'finalised' TSS of Gale to Macdonald.

(That August HW was filming with BBC TV for No Man's Land, a programme made to mark the 50th anniversary of the end of the First World War.)

In mid-October HW had been in London for several days. He collected galley proofs and on 15 October drove down to stay with his daughter Margaret, taking Ossie Jones with him. (Galley proofs are the typescript of a book set on a long continuous roll, and not yet divided into pages.) HW and Ossie worked together on the proofs for three days.

On 16 October he noted: ‘Read all day.’

17 October: Read galleys all day. Tired, voice rough, eyes smarting. Finished 8 pm

He jotted down further changes in the Notes section opposite this entry:

He returned to Ilfracombe on 18 October. Unfortunately the next day Alex Penniall came to tell him she could no longer work for him, as she had 'family problems'; he noted:

I retyped some of the replacement passages in Gale and concluded the job, very tired: have influenza.

(Such statements tended to mean he was exhausted, rather than actually having flu.)

On 20 October he 'wrote an article for D. Express, embodying much that Richard W. sent me re fallow & roe deer.’ (This was series of conservation articles for the 1970 World Wildlife Congress – his son Richard, as a naturalist and writer himself, supplied the background information for these.)

21 October: New galleys 15. Put in para of PM & Miranda lying side by side in green grasses - & parallel this with Mavis & Hawkins. To London. Handed over galleys.

It will have become obvious by now that HW is continuously changing his work at a critically late stage – galley proofs are provided to check for typesetting errors and small corrections only, not for major changes in the text. Some of these changes were following instructions from the editor at Macdonald to cut the overall length – but much was on his own whim. This was shortly to cause problems as will be seen.

All through this period HW was worrying (anguishing) over making his Will and setting up a 'Family Trust': all frustrating and exhausting, making a huge burden for himself and his family. His intention was to leave things sorted for the best for all concerned, but in fact it made everything extremely complicated – so much so that after his death the Trust was legally rescinded as unworkable.

Never long without a writing project in hand, now, on 19 December, he began work on sorting out the material which was to compose Collected Nature Stories.

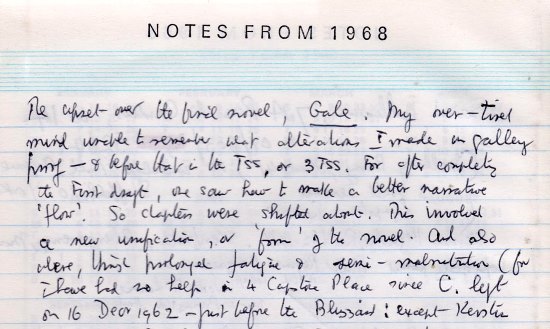

His 1969 diary opens with notes (added later, as he did not know of the debacle until mid-February) about The Gale of the World, and here we see that problems have arisen.

17 February 1969: To London. [He travelled up in the train with Ted Hughes, enjoying this greatly.] Went round & collected copy of Gale. Poor cover. Saw several misprints.

HW was actually on his way to Edinburgh for the inauguration of Ken Allsop as Rector of Edinburgh University. He continued on the next day.

Lovely ride up. Read Gale on way up & was appalled at poor type readers' work (if any) . . . Was presented to Chancellor/Duke of Edinburgh.

He had found the book contained a large number of printing errors – some of which were major. It seems he immediately wrote while in Edinburgh to MacGibbon, explaining the problems with the book. On his return to London on 21 February he:

Telephoned MacGibbon [and it is apparent that his letter with its bombshell information about the huge number of errors had not yet arrived] re errors in Gale & tho' I had suffered somewhat was very nice & easy to him. He said “I feel I've had a heart attack”.

23 February: In all there are 54 misprints, slight changes necessary, & 'literals' (mis-spellings) Also they have omitted owl colophon. MacGibbon of Macdonalds wouldn't allow me to have page proofs which would at least left any blame for errata to fall on me.

That MacGibbon had decided not to let HW have page proofs (the final stage of book production, when the long stream of galley proofs are cut down into actual pages) was no doubt because he was afraid HW would yet again alter things – and in those pre-digital printing days, when type was hand-set, this became a very expensive business. This meant the onus of proof-reading fell on to the printers and/or publishers themselves, and this does not seem to have been carried out. HW had been complaining (to me – and no doubt others) for some time about the fact that the publishers had recently changed hands, and the new staff seemed to him to be young and inexperienced. This was all a tremendous blow to his psychological well-being, at the very moment he thought that he would be celebrating the new book.

24 February [HW must have gone round to the publishers]: The matter of the upset printing of Gale was already decided. MacGibbon had checked with the galley proofs & found it was the printers (compositors) fault. It will have to be reset in places & the edition of 3000 already printed, scrapped.

In fact, not all copies were destroyed, for this happened at such a late stage in the publishing process that a few advance copies had already been sent out; although recalled, not all were returned to the publisher, as copies very occasionally surface in the second-hand book market.

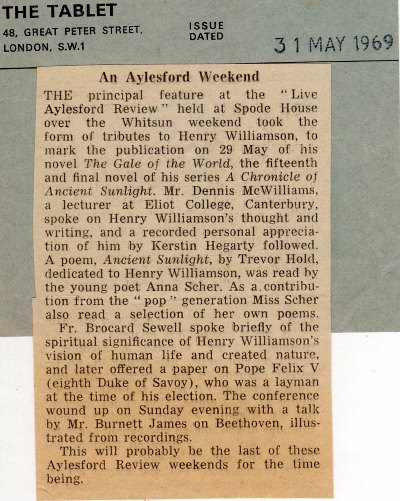

Over the Whitsun weekend (23–26 May), HW with Ossie Jones attended an Aylesford Congress (run by Fr Brocard Sewell of the Aylesford Review) at Spode House, near Rugeley in Staffordshire. The Sunday was devoted to HW's work:

Apparently my day as regards lectures. Professor McWilliams of Canterbury Univ. spoke on my Chronicle & I confess it was too learned for me. [Part of this lecture was reprinted in HWSJ 13, March 1986, pp 10-24.]

In the afternoon we walked on Cannock Chase. Led by two knowledgeable nature boys, wardens of a Lancashire Nature Reserve. Most enjoyable. In the evening, a tape-recording of her two months with me as housekeeper secretary by Kerstin Hegarty. I followed with reading some of the Gale. To bed about midnight.

HW also noted in his diary how he flirted with 'two young women here' – one the poetess named above. On Monday 26 he noted:

The last breakfast – the visit was over. I was sad. It had seemed to be everlasting and joyous. Goodbye to everyone – such friendly feelings and goodbyes.

Then, finally, on 29 May 1969, a very low key entry:

The Gale of the World to be published today.

HW actually went down ('I dared to go . . .') to Exeter to meet MUS in order to celebrate the event, but she was extremely distrait, stating that she had no money, her car needed urgent repair and she was in debt. Having sorted out her problems (he bought the car off her, replacing it with another, and paid her debts), she then became loving to him and he noted he was happy.

*************************

At the beginning of his 1969 diary HW had copied out the following quotation from Don Quixote. It is obviously how he saw himself, and it is a very apt view – a man who tilted at windmills: an eccentric loner who took on 'knightly' causes that didn't really exist and who never really quite understands what is going on, but whose heart was very much in the right place: a man of chivalry – a man with a quest.

*************************

My consideration of the book, HW's photographs and the press reviews are given their separate pages:

Photographic essay (HW's photos of the Lynmouth Flood Disaster, and others)

*************************

Index to The Gale of the World

Between 2000 and 2002 Peter Lewis, a longstanding and dedicated member of The Henry Williamson Society, researched and prepared indices of the individual books in the Chronicle of Ancient Sunlight series (the first three volumes being indexed together). Originally typed by hand, copies were given only to a select few. His index to The Gale of the World is reproduced here in non-searchable PDF format, with his kind permission. It forms a valuable and, indeed, unique resource. The synopsis (with Peter Lewis's delightfully idiosyncratic asides) is not included, as essentially it repeats information already given in the consideration above.

*************************

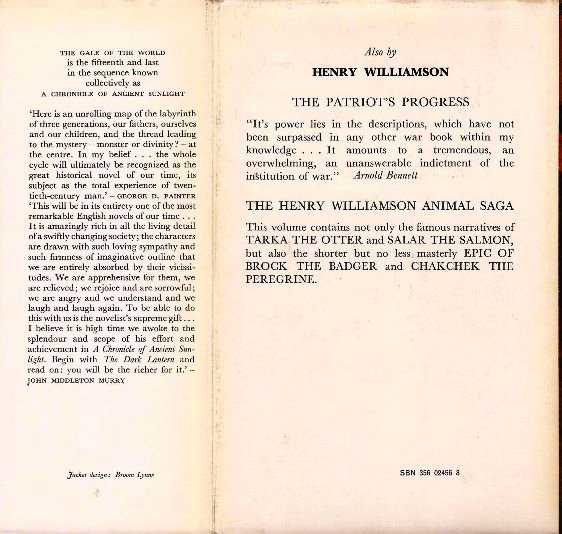

The dust wrapper of the first edition, Macdonald, 1969, designed by James Broom Lynne. Broome Lynne was Macdonald's art director at the time of publication and had designed probably all the covers for A Chronicle of Ancient Sunlight (that for A Test to Destruction is unattributed), but this design is a departure from his usual style, and the outline of a glider, even though stylised, is disappointingly inaccurate: a glider's wings are unmistakably long, slender, and graceful. HW thought it a 'poor cover'.

Other editions:

|

|

|

| Macmillan, hardback, 1985 | Sutton, paperback, 1999 |

*************************

Back to 'A Life's Work' Back to 'Lucifer before Sunrise'