A TEST TO DESTRUCTION

(Vol. 8, A Chronicle of Ancient Sunlight)

‘He faced the spectres of the mind

And laid them: thus he came at length

To find a stronger faith his own;

And Power was with him in the night,

Which makes the darkness and the light,

And dwells not in the light alone.’

Alfred Lord Tennyson

|

|

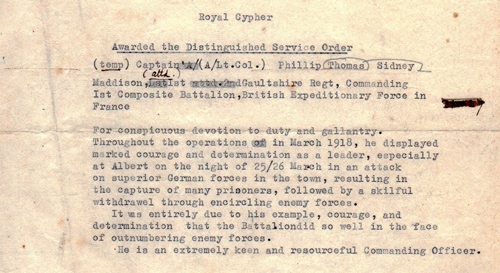

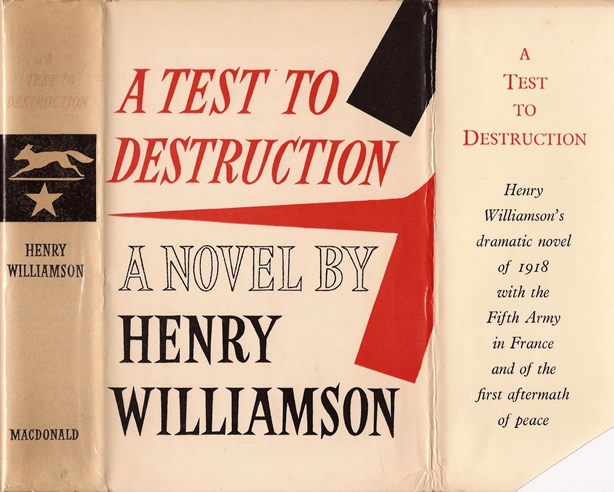

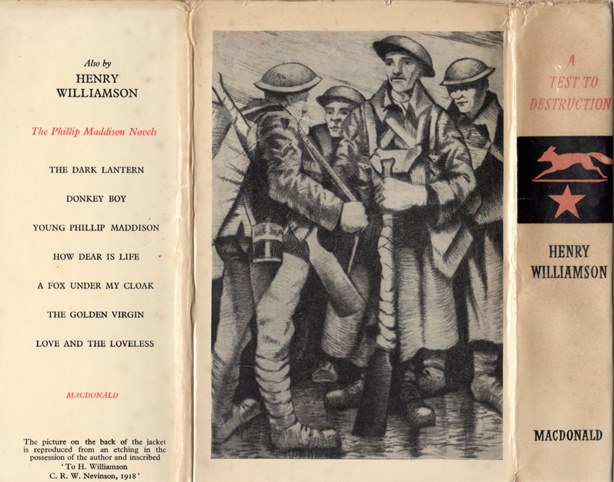

| First edition, Macdonald, 1960 | |

HW's design suggestions for cover

First published Macdonald, November 1960 (18/- net)

Panther, paperback, 1964

Chivers Press, reprint: a New Portway Book for the Library Association, 1980

Macdonald, reprint, 1985

Sutton Publishing, paperback, 1997

Currently available at Faber Finds

Dedicated:

To

GEORGE D. PAINTER

A Test to Destruction (Test hereafter) opens in February 1918, and a harsh winter has been particularly difficult for the poor of London: food is scarce and this has its effect on the Maddison household. Phillip, still passed only as B2 – not fit for active service – is assistant adjutant to the CO, Lord Satchville, at Landguard Camp outside Felixstowe on the east coast, where he feels safe.

In the course of his duties he learns that the Germans are preparing for a massive attack and he changes his name onto the A List (Active Service) and, taking the place of someone who has reported sick, goes back to France, where he meets up again with ‘Spectre’ West, Battalion CO (and triple DSO), 2nd Gaultshires.

The fighting builds up to the main attacks – ST GEORGE I and ST GEORGE II – in early April 1918 against the German offensive along the River Lys (well south of Ypres, north of the Ancre and Somme rivers). At first in the Somme area, Phillip is later moved north to hold Wytschaete Ridge.

Fierce fighting ensues (the scenes are very detailed and harrowing but illuminating of these battles). As the Germans break through Spectre orders withdrawal. Then, as Phillip goes to report to Spectre, a mustard gas shell explodes, seriously injuring West and temporarily blinding Phillip: both are hospitalised.

On the journey back to England their ship hits a mine. Spectre West drowns and Phillip, in distraught state, is taken to the Duchess of Gaultshire’s hospital at Husborne Abbey, where he slowly recovers, learning that he has been awarded the DSO.

He is sent down to Tregaskis House at Falmouth, Cornwall, to convalesce but his wild behaviour (reaction from tension) gets him into trouble. In due course returning to Landguard he asks for a transfer to the Indian Army, and is actually about to leave when, on 11 November 1918, the war ends. The transfer is cancelled.

In the new year he is transferred to Shorncliffe (Folkestone, Kent). He meets Mrs Evelyn Fairfax (the heroine of his earlier book The Dream of Fair Women, part of the Flax of Dream series), buys the latest Norton road-racing motorcycle, and generally creates mayhem! He is transferred to Cannock Chase where his difficult behaviour quickly earns him demobilisation.

Living back in the family home, Phillip soon gets into trouble, quarrelling with his sisters and father, to his mother’s constant distress. He finds himself encumbered with the objectionable Tom Ching, going briefly to prison on Ching’s behalf. He then settles down when he obtains a humble job in Fleet Street and begins writing his first novel. Gran’pa Turney dies amidst controversy over his Will. But the novel ends on a quiet note of hopeful life for the future. (An optimism not easily fulfilled as will be seen in the later volumes!)

*************************

The dedication: George Painter, OBE (1914-2005) was employed as Assistant Keeper of Printed Books (particularly as specialist in fifteenth-century printing – known as ‘incunabula’) at the British Museum; he retired in 1974. In the late 1940s and early 1950s he wrote reviews for The Listener and The New Statesman. He wrote several works on French writers and men of letters, including André Gide (1951), William Caxton (1976), Marcel Proust (2 vols, 1959, 1965), which won the Duff Cooper Memorial Prize in 1965, and Chateaubriand, which won the James Tait Black Memorial Prize in 1977. He was particularly an admirer of HW, John Cowper Powys and Sylvia Townsend Warner.

Painter had written to HW expressing admiration of his work, and when HW was worried about beginning the Chronicle and the problems surrounding its publication, he asked Painter for his opinion of the typescript of the first volume. Painter indicated that he found it very good, which gave HW the confidence to go ahead.

Painter’s writings on HW’s work include ‘The Two Maddisons’ (Aylesford Review, vol II, no. 6, Spring 1959), and ‘The Ex-soldier and the Otter’, a review of Tales of Moorland and Estuary.

It is Painter who referred to HW thus:

He stands at the end of the line of Blake, Shelley and Jefferies: he is the last classic and the last romantic.

*************************

The title page quotation:

He faced the spectres of the mind

And laid them: thus he came at length

To find a stronger faith his own;

And Power was with him in the night,

Which makes the darkness and the light,

And dwells not in the light alone.

These lines are from In Memoriam A.H.H. (pub. 1850) by Alfred, Lord Tennyson (1809-92): a paean of sorrow (if that is not a contradiction) for the untimely early death of his close friend Arthur Hallam in 1833, which passes through the various stages of grief: shock, despair, resignation and reconciliation. These lines come from Canto 96, well into the poem. They are not idle lines and HW means us to take note of this concept as underlying the content of Test.

That quote contains more than one sub-text within HW’s use of it. First, Tennyson’s own purpose in recording the death of his friend and mentor. So also in Test, HW is recording the death of Brigadier-General Harold West, friend and mentor of Phillip Maddison. But Tennyson’s own purpose was wider and deeper than just that obvious aspect: In Memoriam is a reflection of nineteenth-century thought. We know that HW’s purpose in the Chronicle as a whole unit encompasses much of twentieth-century thought: that underlying wider aspect which is a central theme within HW’s writings (particularly within the ‘war and peace’ aspect).

The third subtext is more obvious. HW could doubtless have chosen many passages from Tennyson’s poem to preface this book: he chose one containing the word Spectre – reinforcing the thought of Spectre West. I have stated elsewhere that the nickname of Spectre is a clue to the fact that this character did not exist in real life – he was a wraith from HW’s imagination (see HWSJ 34, September 1998, Anne Williamson, ‘Some thoughts on Spectre West’, pp. 86-94). Spectre is in effect HW’s alter ego: thus it is himself that HW is mourning – the loss (death) of his youth, but also the literal untimely death of thousands of his comrades, including several who were his friends.

The fourth ‘message’ hidden here concerns Phillip’s (and thus HW’s) attitude to his own experience of war. By the end of the book he has faced its horror and fear – although it is obvious he was forever deeply maimed – but he is becoming resigned and reconciled. We know from his writings in his early 1920s ‘Richard Jefferies Journal’ that he found strength from the ‘Power’ that made the natural world: a deeply philosophical concept even though not expressed in such terms, a searching for Truth which underpinned his life thought and his writing. It also reflects the ‘light and darkness’ (good and evil) theme of later novels: that Platonic concept of opposites – one cannot understand something without its opposite: to comprehend ‘light’ one has to have ‘dark’: therefore to comprehend ‘good’ one has to have ‘evil’.

*************************

The writing of this volume appears to have been quite difficult, due partly to domestic problems, but sorting out the structure and the theme of this last war volume was obviously very complicated.

HW noted in his 1958 appointment diary on 3 November: ‘To begin re-start No. 8 today.’

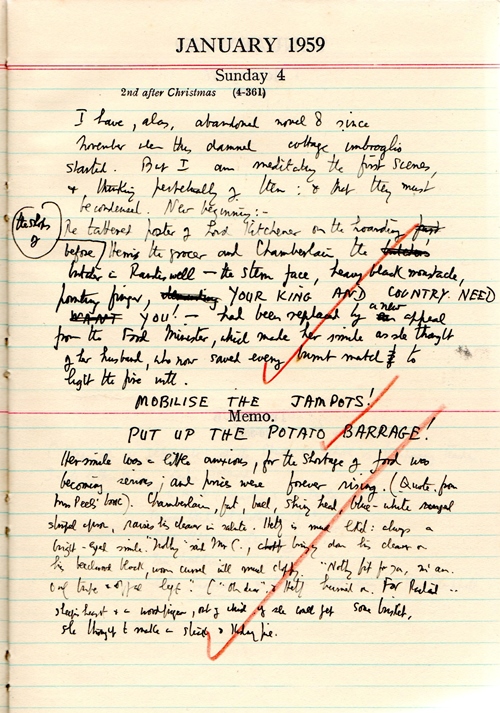

The next time he mentions this volume is on Sunday, 4 January 1959:

I have alas, abandoned novel 8 since November when this damn cottage embroglio started. But I am meditating the first scenes & thinking perpetually of them, & they must be condensed. New beginning.

The ‘cottage embroglio’ involved the problems over the renovations at the cottage he had bought in nearby Ilfracombe: a constant source of irritation on which he spent a great deal of time and energy: not conducive to writing a complicated novel.

That January Christine commenced teaching at a school in Ilfracombe, which Harry also attended. HW had to drive them there every morning from the Field, 28 miles per day he noted – which meant more lost time (and money spent on petrol). Once there he visited the cottage to oversee and inevitably find fault with the various processes such as retiling the bathroom and kitchen – but particularly the sitting room fireplace over which he was very fussy – his orders were never carried out to his satisfaction, so he tended to do all the work himself, often undoing that which the builder, Ernie Brown (that same Ernie who featured as a young child in the Village books), had done the day before! At one point he got badly stuck in the snow which did not help the situation.

On 12 January he received a letter from Charles Causley (poet of renown and friend of HW) about Love and the Loveless, which cheered him up greatly:

I feel I can soon begin No 8 – or renew the start – with almost elan.

Grand letter from Marjorie Dawson [a cousin] about the novels. “To read them before a fire, snow outside, is my idea of bliss.”

Saturday, 24 January: Finished the cottage hearth at 7pm. this night. Thank heaven, I may now be able to devote myself to No. 8.

28 January: Posted first chapter of No. 8, pp. 1-38 to Elizabeth Tippett [typist in Cornwall]. A good chapter I felt. Too much building up, like a coral reef. However, I must end the war, Armistice, by Chapter 4. The story, after all, is largely the post-war development, and not the war. [That ‘chapter 4’ was not kept to, as will be seen.]

11 February: Floor of cottage still undone. Novel still unprogressing. Cannot write with the underlying tension of builder Brown’s negligence.

11 March: Corrected last batch of proofs of revised Shallowford book[The Children of Shallowford (1939), new edition 1959 – there has been no previous mention of this work in progress.] Fabers catalogue gives pride of place to Richard’s Dawn . . . I come next. Most satisfactory. [The Dawn is my Brother was the first book by his son Richard Williamson.]

For some time HW had been worried about and frustrated by the failure of Clibbet Thomas, sexton of Georgeham church, to sort out his grave plot in Georgeham churchyard (there being little space left), and Christine’s inability to deal with it. On Sunday 15 March he recorded that Clibbet Thomas had died that day:

so even his poor faulty memory won’t be available to remember the new site of the grave – by a CASTOR OIL TREE planted by Miss Hyde some years ago. (“Miss Goff of The Pathway”).

Various worries keep cropping up, business and family: obviously most are a product of overstress. A memo here states:

Quite ill with overwork. Worried about the animal saga book [and his Will, family etc.] [This is The Henry Williamson Animal Saga, (Macdonald, 1960) – problems arose over the selection of material.]

Entries in his diary tend to be somewhat sporadic – no doubt due to the amount of work and stress. At some point here he actually moves into the cottage in Ilfracombe.

Friday, 17 April: pp. 39-95 of No. 8 (Chapter 2 & 3) sent to E. Tippett.

On Monday 27 April Christine and their son left for York (visiting Christine’s mother): HW took them to Bristol station and continued on to Bungay via Oxford (to visit S. P. B. Mais in his new house: ‘he was less farouche and bitter’), and then Thelnetham in Norfolk to see John Murry’s widow Mary Murry and her friend Ruth Baker, first visiting Murry’s grave (J. M. Murry of Community Farm fame, owner of The Adelphi before handing it over to HW, and author of comprehensive essay on HW’s writing) – before finally reaching Bungay, arriving after midnight. While there he visited Adrian Bell (writer and friend) at nearby Beccles, and Lilias Rider Haggard (with whom he had collaborated over A Norfolk Life (1943), see entry in due course) at her home, the Bath House, Ditchingham, Norfolk – the village neighbouring Bungay. He returned home on 4 May with his son Richard, picking up Christine at Bristol station en route. He had stopped at Oxford, recording:

Saw Canon R. R. Martin, old 16th Foot, war comrade, for a few minutes at 1 p.m.

Richard stayed till the end of the month: they went to the West Country Writers meeting at Bristol, 22-23 May, where HW made a speech responding to ‘Guest, C. S. Forrester’: ‘Did so, with Goon-like jokes’. L. P. Hartley was also present as a guest. In August Mrs Allsop (Ken Allsop’s wife Betty), and their children Amanda and Fabian, plus a French girl, stayed at the cottage for four weeks. It is unsurprising that work on novel no. 8 was slow!

On 23 September HW recorded: ‘1000 words Richard Jefferies to Farmer’s Weekly; 500 words 1914 Time and Tide.’

27 September: 1500 words on 1914 for Time & Tide sent off. (500 ordered)

On 7 November HW gave a lecture to the Richard Jefferies Society in Swindon (he served as its President from 1965-75) and went on to Bungay afterwards. His pocket diary for 9 November records: ‘I made a new start on No. 8 novel.’ This is a whole year since he first re-started this volume, which demonstrates the difficulties that he found with it. Again in the pocket diary, he recorded on 15 November: ‘Have written 2500 words of No. 8 & more or less delighted myself with discoveries in imagination.’

In the Notes section at the end of this pocket diary he has copied out the John Donne quotation:

Thou knowst how drie a Cinder this worlde is

That ’tis in vaine to dew or mollifie

It with thy tears, or sweat, or blood

John Donne

from An Anatomie of the Worlde

used p. 179 (typing) of No. 8

3 January 1960: Possible quotation for Title page of

A TEST TO DESTRUCTION

‘Innocence and independence make a brave spirit. Thomas Fuller.

13 January: No. 8 novel limps on. An old sweat in the Britannia today suggested a good title “for the end of the novel – WAX END”. God knows how it is spinning itself out. I haven’t been able to follow my synopsis – or look at the various synopses – am now at Mss page 460.

19 January: Plodding on with No. 8. I go daily (5 times weekly) [remember he is now living in Ilfracombe] to the field & write there, either in caravan or studio, fires being made there on arrival. The novel is getting very long. I have been unable to keep to the various synopses, not wanting to look at them! . . .

20 January: [long entry] I have not written in a diary for some weeks/months. Reason, fully worried & extended (like a worn bit of elastic garter) over No. 8. Last night, feeling I had got rather off the direct drama, I decided to scrap all the Folkestone Jan – June 1919 [part 4] which consists of pp (in my Mss-Tss) 425-489. The book is being drawn out . . . [instead – as follows –]

21 January: [in red ink] Part 4. T.T. [Thomas Turney] in his chair, reflecting.

Phillip is about to come home – the next day.

T.T. asks,” Any more about that woman at Folkestone?” Then, the M.F.O.?

Dickie is very worried, Phillip didn’t answer the letter from the General Secretary [of the Moon Office about returning to pre-war job].

Philip in his cubicle on Cannock Chase.

30 January: I took pp (my Mss) 346-457-492 to Elizabeth Tippett near Launceston.

Received from her pp. 312-498 (her pagination)

Made a tape recording there of a chapter of No. 8 (T.T. in armchair) and also a bit of Richard !! (Shakespeare). Bad, woolly, fatigued voice.

The title of A Test to Destruction was originally the title for Victor Yeates' book Winged Victory (published in June 1934) which was rejected by his publishers as meaningless – particularly noted by HW at the end of his own book The Linhay on the Downs:

'no one seemed to know what that meant except the author and his friends who were human flesh and spirit tested to destruction . . . ' (p. 309)

At this time HW was editing Letters From A Soldier by Walter Robson. ‘Edited Tss’ – on March 17 he recorded he was writing the Introduction for this for Faber. (It was published in 1960; HW’s introduction has been reprinted by the HWS in Threnos for T. E. Lawrence and other writings, 1994; e-book 2014). The Henry Williamson Animal Saga was published in February 1960.

4 February: . . . Thought about my No. 8 novel: now that it is to end after prison with P. Beginning a job. I can put back the scrapped Part 3, or 4, at Folkestone.

5 February: E.T. sent me pp 433-453. I wanted 433-492.

18 February: No. 8. Took pp. 433-592 to E. Tippet. Stayed to supper.

19 February: Writing – absorbed. [And in ‘Notes’:] Writing – pale but proud.

23 February: I finished No. 8 today. On a quiet note. About 600 of typed pages – perhaps 150,000 words. Possibly the most complete novel I’ve ever written: or should I say that has written itself (the ‘Imagination’ of JM Murry’s urging). It was started in Nov. 1958 & irrupted [sic] by major breaks twice.

25 February: Retyping many of the much rewritten pages.

27 February: [the same] very weary & puffy with nicotine & desk galls.

On 9 March he took the retyping to E.T., while on 17 March he is still retyping and also doing the introduction for Letters From A Soldier (as above).

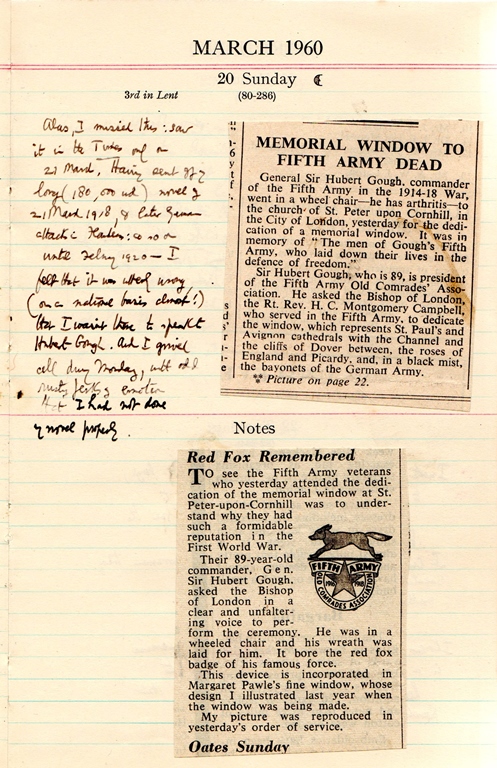

20 March:

He wrote a letter to Captain Gough, nephew of General Sir Hubert Gough, to apologise for his absence.

On 21 March HW sent a copy of the TS to Eric Harvey, his current editor at Macdonald, worrying that it was far too long and guessing at the passages he would be asked to cut. But he cut some thorns on the bank behind the caravan and felt much better for some physical work (always his panacea – ‘needed to sweat’).

On Friday 1 April he notes that he is already working on, or thinking about, the next volume!

As with Love and the Loveless, HW took a keen interest in the design of the cover and indeed the blurb to be used on it, and fragments of notes and letters survive that he sent in July to Walter F. Parrish, a director at Macdonald, together with Parrish's no-nonsense response. These are shown on a separate page. It is not known who designed the cover – there is no mention of James Broom Lynne in the correspondence, neither is Broom Lynne credited on the dust wrapper. In view of HW's opinion of Broom Lynne's interpretation of the two hands clasped in comradeship for the dust wrapper for Love and the Loveless ('Too insensitive. The Soviet-tractor statistics factory comrades clasp in concrete', HW noted on his own copy of the book), it may even be that HW asked that Broom Lynne not be involved with this next novel.

During August HW visited John Heygate at Bellarena (on the north coast of Northern Ireland) with Richard, but became tetchy because proofs of Test were about a month late arriving. Having returned, sections of proofs arrived daily from 5 September, and were dealt with daily for about two weeks. On 4 November he recorded attending the ‘L.R.B. Dinner’ (the Chyebassa reunion of the original London Rifle Brigade): and at this time he was having his portrait painted by his son-in-law, William (Bill) Thomson.

Publication of A Test to Destruction was in November 1960, but was not recorded by its author. Also published that autumn, and again not recorded, was a short biographical item In the Woods (see entry in due course).

*************************

The title of this volume, A Test to Destruction, was pushed back from the previous volume, but that was because the content itself was pushed back. Title and content are therefore still joined as originally conceived in so far as the overall theme of the book is concerned. It covers a very complicated, confused and critical time within the war, so some detailed commentary is necessary.

The book is basically about courage: courage tested to the point of destruction – here within the last stages of the war, but further as a concept for the whole war. The various quotations that occur as part headings or within the text all serve to emphasise that concept. But ‘destruction’ is also used as a metaphor for more literal destruction: that of the structure of the actual landscape fought over, and of the old pre-war Europe.

Thus we have a further quotation from The Anatomy of Courage (1945) by Lord Moran (Part Three, p. 209): ‘For what peace of mind can any man have if his honour is no longer in his own keeping?’

Lord Moran, Sir Charles McMoran Wilson (1882-1977) served in the Royal Army Medical Corps in the First World War and was awarded the MC in 1916. The Anatomy of Courage arose out of his experiences of that time and his further studies into this subject. During the Second World War he was Churchill’s personal physician, and was President of the Royal College of Physicians from 1941-50. The subject of the book is fear and man’s attempt to overcome it (courage). Moran asks: ‘Why can a man appear to be as brave as a lion one day and break the next?’ – and what can be done to delay or prevent ‘the using up of courage’? His subject (call it shell-shock, battle fatigue, nervous breakdown) is as pertinent today as it was then.

HW’s use of this reference tells us that he was aware of the content of the book and means it to be thought of in context with his own book. Phillip is constantly afraid but manages to overcome this by various strategies which have become more sophisticated as he gets more experienced; and HW shows various examples of courage and cowardice in other characters, particularly in this volume. The quotation fronts Part Three, ‘Tension’, and I will discuss it at that point in the synopsis.

Also HW quotes a passage written into the front of a diary for 1856 written at Sebastopol, and belonging to Augustus Williamson, son of Sir Hedworth Williamson of Durham, whom HW felt was part of his own ancestry (Part Four, p. 313):

‘A man may bear a world’s contempt when he bears that within himself that says he is Worthy. When he contemns himself – there burns the Hell —‘

The words are from the Scottish poet Alexander Smith (1830-67), from his long poem ‘A Life Drama’, but the poet also wrote a series of poems on the Crimean War. The point is that the diary is about the last year of the Crimean War and all the factors involved. Although it is not necessary for the ‘enjoyment’ of this book, it helps in the wider understanding to take that on board. Remember, that was the occasion of the Charge of the Light Brigade, when men obeying their call to duty went courageously to their death even though they knew they were obeying a faulty order. ‘Theirs not to reason why, theirs but to do and die.’ Chapter 2 of Test is actually entitled ‘What is Courage?’, which I will examine in due course.

The book is divided into five parts: Part One, ‘Anticipation’: 18 February–21 March 1918; Part Two, ‘Action’: Evening 21 March–22 April 1918; Part Three, ‘Tension’: May–September 1918; Part Four, ‘The Lost Kingdom’; Part Five, ‘No-Man’s-Land in Civvy Street’.

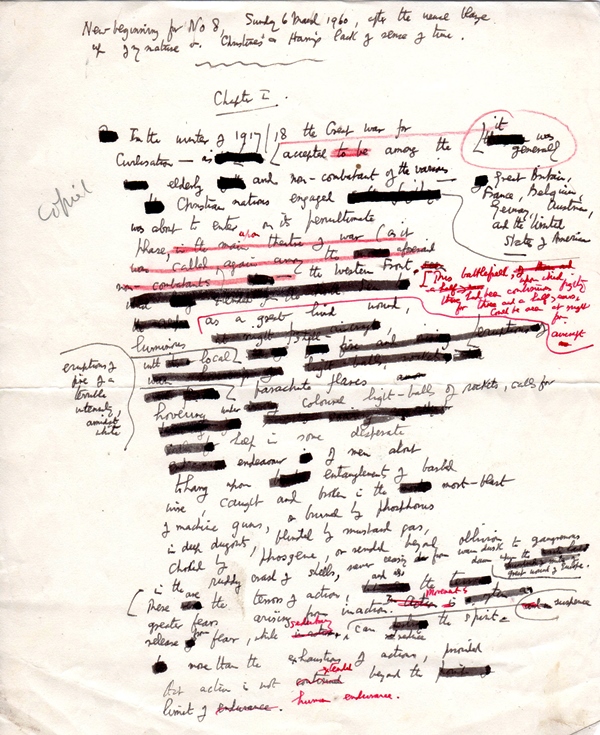

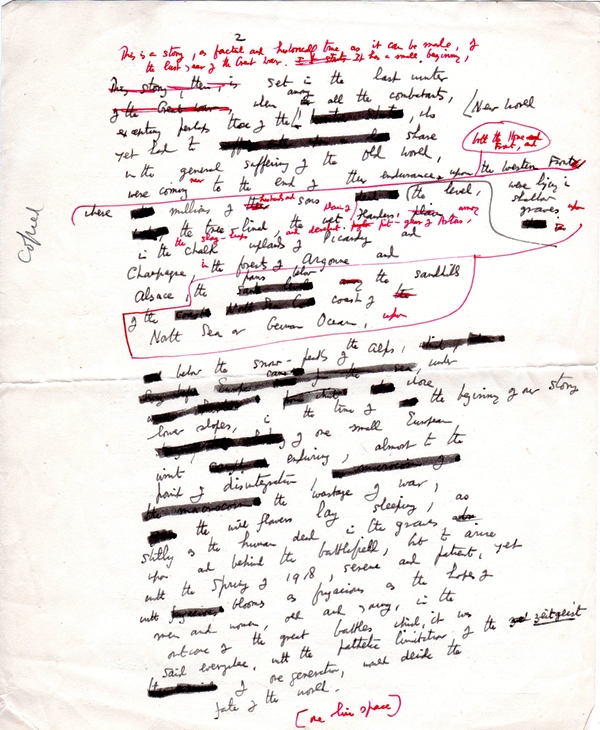

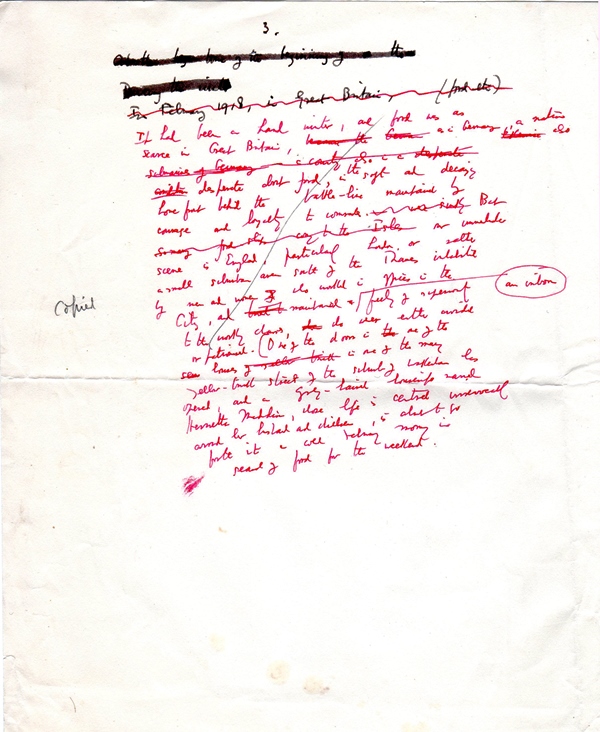

HW's three-page MS draft of the opening paragraphs:

Part One, ‘Anticipation’: 18 February–21 March 1918

HW opens with a passage outside the walls of his novel: an overview of the situation presented in the last year of the war. It is worth quoting in full, not just for its intrinsic value but as a superb piece of descriptive writing.

In the winter of 1917-18 the Great War for Civilization . . . was about to enter its penultimate phase on the Western Front.

This battlefield, upon which there had been continuous fighting for three and a half years, could be seen at night from aircraft as a great livid wound stretching from the North Sea, or German Ocean, to the Alps: a wound never ceasing to weep from wan dusk to gangrenous dawn, from sunrise to sunset of Europe in division.

During this war there were the terrors of action at the front, as well as mortifying fears arising from comparative inaction at home. Movement is often release from fear; while sedentary suspense can reduce the spirit more than the physical exhaustions of action.

This is a story of the last year of the Great War, and of the year following the first silence upon the battlefield. It has a small beginning, set in a time when all combatants, except perhaps those of the United States – who had yet to share in the general sufferings of the Old World – were coming to the end of their endurance upon both the Home Front, and the Western Front – that deadly area where millions of husbands and sons had fallen, in the coastal sandhills beside the Channel; in the brown, the treeless, the grave-set plain of Flanders; among the slag-heaps and derelict pithead-gear of Artois; upon the chalk uplands of Picardy and Champagne; in the forests of Argonne and Alsace extending to the neutral country of Switzerland – where below mountain peaks, under the snow, wild flowers lay resting as still within their corms and bulbs as the human dead upon the battlefield.

As the great battles of the Spring of 1918 broke upon France and Flanders, so the flowers of the upland valleys arose with blooms as fugacious as human hopes for the outcome of the war, which, it was said everywhere, would decide the fate of the world.

The story proper opens with a scene establishing the shortage of food and rocketing prices in the harsh winter of early 1918. Hetty Maddison (Phillip’s mother) is not very good at procuring either meat or vegetables, and her husband Richard is constantly irritable due to undernourishment and the long hours at his work and as a sergeant in the Special Constabulary, which he takes very seriously indeed.

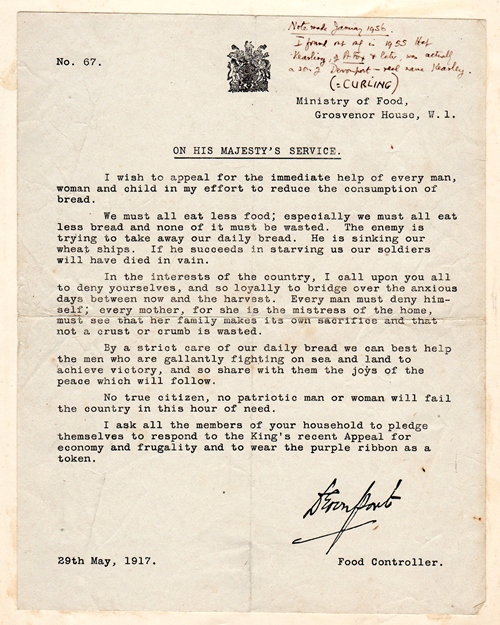

|

|

Henry's annotation reads: 'Note made January 1956. I found out only in 1955 that Kearling, of A Fox and later, was actually a son of [Lord] Devonport – real name Kearley. (=CURLING)' (Note: Oddly, A Fox Under My Cloak has no such character; however, Lieutenant Curling does make a brief appearance in The Golden Virgin.) |

Phillip has settled in as assistant adjutant at Landguard Camp, situated behind Landguard Fort at the mouth of the River Orwell just south of Felixstowe on the Suffolk coast. He is billeted at No. 9, Manor Terrace (as in real life: a plaque was recently erected nearby recording HW’s service there).

Phillip deals mainly with the records of post-convalescent men returning to duty. He and his room-mate, nineteen-year-old Jimmy Allen (his real name) go for a swim each morning, as does the CO, Lord Satchville, ‘a tall Viking bearded figure’ (Lord Ampthill, cousin of the Duke of Bedford), whom Phillip likes very much. (HW had some connection with Lord Ampthill post-war – and actually invited him to the Hawthornden Prize ceremony.) Phillip has bought a small fox-terrier, Sprat, the runt of the litter, which gives him much needed affection. He is also much calmer: ‘A regulated life had given regulated thoughts.’

He is still graded B2 on his medical record (fit for Home Service only – as was HW at this point).

Chapter 2, entitled ‘What Is Courage’, reveals very subtly how clever the cowards could be at avoiding the front line, while Phillip, considered by others and indeed himself to be a coward, deliberately arranges things so that he will again be sent out to the Front. Deciding he wants to get back to France (in the novel to keep his own father from enlisting), he switches his name to the A list (for Active Service), knowing through his work that a German offensive was imminent. HW recorded doing this himself (as Adjutant he had access to the records) in his diary for 1 March 1918. This was indeed quite an act of courage, as he was actually terrified of the battle front line. ‘He faced the spectres in his mind.’

At home a telegram arrives stating that Phillip’s cousin Gerry Cakebread (based on HW’s cousin Gerry Simpson) has died of wounds. Phillip’s sister Doris meets a seemingly strange young soldier, Bob Willoughby, who had known Percy Pickering. (In real life this was Bill Busby, whose name appears above that of Charlie Boon in the MGC List 26, July 1916: see HWSJ 43, September 2007, p. 100.) Mavis, now insisting on being called Elizabeth, doesn’t like Willoughby: ‘There’s something wrong with him.’

Phillip leaves his dog with Mrs Neville and returns to Landguard where, hearing a draft is leaving for the Front, puts his own name down instead of the confidence trickster Wilkins, who reports sick. He sends a telegram to Lt-Col. West to say that he is on his way. They arrive in France and entrain, passing through a desolate landscape:

From both sides of the carriage were to be seen, for mile after mile, the wastes of the old battlefield of the Somme. Tens of thousands of wooden crosses stood out of flattened grasses which scarcely concealed shell-holes, edge to edge, extending to all horizons. Not even the brick rubble heaps of villages remained; all had been cleared for road mending.

Their destination is ‘Corunna’, or ‘White City’ Camp, where they find the Quartermaster, Colonel Moggerhanger (‘Moggers’) – quite a character, based on Colonel Cressingham, 2nd Bedfordshires – who tells them the rest of the battalion is in the trenches. That night Phillip sees flares denoting an attack, and the next morning the badly mauled battalion marches back in:

. . . led by Spectre on foot, his one eye staring ahead under the rim of his helmet. He took the salute, his face white and set.

Behind him is Denis Sisley from Landguard, looking haggard and ill (again, his real name – as are many others here). The depleted battalion is now out at rest. Drafts of young soldiers arrive to make up numbers. Phillip writes home using a code embedded in his letter to explain where he was actually stationed: PERRONNE (as HW had done in 1917 letters home from the Front). Peronne is south-east of Albert on the Somme.

|

| Denis Sisley, MC |

(For other photographs of HW's fellow officers and his time with the 3rd Beds, see HW at Felixstowe page.)

A chapter entitled ‘Pig’ tells the tale of a court of enquiry convened to sort out the claims of a French farmer. It is quite a hilarious tale, but its underlying purpose is to show how the French farmers were using the reparation system to make big profits (this was all based on a true story!).

Sisley goes sick and Phillip becomes Adjutant (to the CO, Col. Spectre West) with Allen as his assistant. Spectre orders Phillip to accompany him on a recce of the forthcoming battle zone. They rendezvous at the Aviary and continue to the battle redoubt, and then on to the outpost line. All is very detailed, and the reader learns exactly what will be involved.

On the return journey Spectre and Phillip discuss the situation. They also have a personal conversation, which reveals Phillip’s psyche to the reader. On their return Spectre promotes Phillip to acting Captain.

That night a signal arrives with the codename RAINBOW: ‘Prepare for Attack’. Phillip makes the necessary arrangements to put all on alert. Another message: the battalion move into position – and the attack begins.

This is the German offensive of 21 March 1918 known as the ‘Kaiserschlacht’ (the Kaiser’s Battle). Although there are no official records to confirm the fact (in the chaos of that period official records were either not kept or were destroyed), there is some archive evidence that HW did return to France for a short period in March/April 1918. (See Paul Reed, (the eminent WWI historian), ‘Henry Williamson and the Kaiserschlacht’, HWSJ 18, September 1988, pp.12-15; Dr M. Maloney, ‘A Test of Detection’, (scanned in two parts: Part two) HWSJ 43, September 2007, pp. 30-49; Anne Williamson, Henry Williamson and the First World War.)

Part Two, ‘Action’: Evening 21 March–22 April 1918

Spectre sends Phillip back to Brigade HQ with information where, to his frustration, he is kept until an order to retreat arrives. But a German machine gun is covering their exit route. Phillip and his sergeant take a Lewis gun and manage to take the Germans out, and the retreat is completed. This German attack was coded MICHAEL.

On regrouping messages arrive. One contains orders to fight a rearguard action to new lines: a second informs Spectre that the Colonel is dead and he is to take command – leaving Phillip in command of the Battalion. The ensuing German advance is met in good order but a further attack means retreat to the Canal du Nord. They retire to Railway Wood, to hold at all cost, but are surrounded by Germans.

Phillip goes on a recce with O’Gorman (the Irish orderly who now becomes his batman). They are captured but escape that night, and after a spat with the Germans with much difficulty manage to get back to their own division, now known as ‘West’s Force’. While Phillip has been away, Captain Kidd has relished being in charge.

West’s Force, exhausted, is taken into reserve above Albert: Spectre and Phillip stand in the Grand Place and watch the ‘fought-out men of the scattered and seldom co-ordinated rear-guard’ filing past. Spectre remarks (HW laying down a marker): ‘What a scene for some Tolstoi of the future!’

Spectre has written into his pocket book some lines from John Donne (remember HW’s diary note) – which will actually come into prominence in a later volume. (HW puts it here as another marker – which shows he has planned well ahead.)

Thou knowst how drie a Cinder this worlde is

That ’tis in vaine to dew or mollifie

It with thy tears, or sweat, or blood.

This is followed by another reference to the story of ‘the legendary Golden Virgin’, which reminds Phillip of Lily Cornford. He has grown beyond the man he was then in 1916: but as he lays exhausted he thinks of his boyhood.

Behind closed eyes he was a boy biking along a white dusty lane, making for the dappled woods of Spring, happy, happy, happy with Desmond. The picture was stricken; everything had an end; the opening of a flower brought about its own death. Before the flowering of Lily, he and Desmond were the greatest friends who had ever lived, their friendship was to last for ever and ever in their lives.

This becomes more poignant to readers today who know that despairing phrase added to his boyhood ‘Nature Diary’:

Finish, Finish, Finish, the hope and illusion of youth,

For ever, and for ever, and for ever.

Readers following HW’s writing will notice the covert reference there: the phrase ‘opening of a flower’ harks back to his early book about his boyhood, Dandelion Days – while ‘happy, happy, happy’, is a phrase used by Dryden in ‘Alexander’s Feast (1697)’: ‘Happy, happy, happy, pair! . . . None but the brave deserves the fair.’ Alexander the Great was of course a war-lord. (It also comes into Chekhov’s play The Three Sisters where it has a more ironic connotation.)

Phillip is now the officer commanding No. 1 Composite Battalion, based on a real ‘composite battalion’ (see AW, Henry Williamson and the First World War, p. 144, where some background to this is given). When on defence guard duties a shell bursts overhead.

When the smoke had cleared the leaning figure on the broken campanile was not to be seen.

Bill Kidd is jubilant: ‘Golden Virgin has come down! The bloody war’s going to end this year!’ – the legend being that the war will not end until the Golden Virgin falls (a soldiers’ superstition which doesn’t actually bear analysis).

With orders to defend against German attack, Phillip stays put, then realises that he and his men are cut off from withdrawal. Going on a recce he discovers the Germans are unarmed and unprepared: they set off to capture them, resulting in 142 prisoners!

The following day this No. 1 Composite Battalion march out of the line west to Bresle, where it was disbanded and the men returned to their original units. A few days later the 2nd Gaultshires are ordered by slow train back up to St Omer (where Phillip/HW had first been in November 1914) and on to Poperinghe: they learn that General Gough has been removed from command of the Vth Army (this was an iniquitous event – rescinded in later years: but the Government needed a scapegoat at the time).

It was like old times again – almost.

One of the main nuances emanating throughout this episode is how little has changed or been gained over the course of the four years of war. Areas have been fought over and won and lost, won again and lost again.

In the first week of April 1918 they are about to face the formidable German attacks codenamed ST GEORGE I, to be followed by ST GEORGE II. Moggers goes sick and returns to England. Spectre is given command of the Brigade, and puts Phillip in temporary command of the Battalion. Kidd (who is now drinking rather too steadily and ridicules everything Phillip does) objects, so is made second-in-command.

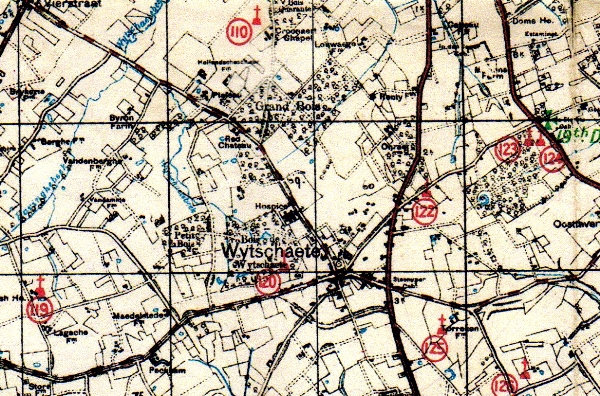

Phillip and Kidd take out a wiring party into No-Man’s-Land: Kidd overhears German movement and they escape a small bombardment. The following night there is a gas attack. The ST GEORGE attack is imminent and everyone is worried. The Germans break through the Portuguese-held line. Spectre states that they are to support the Scottish Division: Messines has fallen and they are to hold the high ground near Wytschaete at all cost. Phillip is very nervous but goes round his men with a personal message. Kidd does not approve – he is a ‘Boche eater’ and thinks the men should be incited with fiery fervour.

The men move up into position on the Menin Road ‘towards the ruins of Vierstraat (which featured in the 1914 scenes). They proceed to the Grand Bois (again 1914). Bill Kidd becomes more difficult under fire: he captures a pillbox (Staenyzer Kabaret: marked on HW’s detailed map as situated at the crossroads just east of Wytschaete) and sets himself up there – ‘Kidd’s Post’ – overlooking Oostaverne (a village to the east). Phillip establishes his HQ in Wytschaete itself.

Kidd ‘obtains’ (i.e. pinches) two motorbikes from an MG Battery and goes off to butcher dead horses for meat. The MGC major is furious: his orders were to go to Hill 63. Kidd does not care and is drinking hard. Hill 63 (on the north-west corner of Ploegsteert – ‘Plugstreet’ – Wood) comes under heavy attack and is taken.

Spectre’s orders are now to withdraw, but Kidd (whiskey aggressive) belligerently stays put – causing problems; and in due course he gets captured by the Germans. The new advanced Battalion HQ is at Byron Farm, south-east of Vierstraat, beside the road just before the Grand Bois. Spectre wants to see Phillip (who presumes he is in trouble over Kidd’s behaviour, which he should have controlled).

As Phillip approached Byron Farm to report, Spectre leaves the dugout to meet him and at that moment is hit by a mustard gas shell on his legs, severely wounding him, the mustard gas splashing on to Phillip’s face, temporarily blinding him. They are both taken to the CCS (Casualty Clearing Station) at Kemmel and then separately on to the American Hospital at Entretât, helped by both O’Gorman and Spectre’s batman.

Back in England Thomas Turney has heard that his grandson Tommy (his estranged son Charley’s boy) is dangerously ill from wounds in the South African Hospital at Abbeville in France. He plans to visit with Hetty, explaining to her that there is a system in place to enable this to happen through the YMCA (another ‘social history’ point). Before she leaves a telegram arrives announcing Phillip has been blinded temporarily, but this is more or less kept from her. (There is the usual family squabbling over all this with the two girls.) The journey reminds Hetty of her schooldays at Thildonck in Belgium. When they arrive at the hospital they find Tommy is dangerously ill and not expected to last the night. The next day they attend his funeral. It is all rather prosaic. On her return she realises how near to Phillip she has actually been and that she could have visited him.

This is all rather an odd little episode: what has happened to Phillip seems of little consequence to anyone. The person most affected is his father, but he soon recovers. It is not clear what HW’s purpose was – other than to extend the overview of the war. It does illustrate the actual emotional distance between Phillip and his mother rather cleverly. And it furthers the idea of Phillip as ‘outsider’ – which is of course a major factor of HW’s own personality.

Phillip is far more concerned about Spectre than himself but they are separated and he cannot get contact with him. They are both to embark on a boat for England, the Persia. Phillip is worried about being seasick, especially as the cork lifebelt constricts movements already hampered by his blindness, but he is more worried about Spectre. He sends O’Gorman off to find him. Out at sea the ship hits a mine and sinks. They are picked up by a destroyer escort, but Spectre is drowned: he had given his own lifebelt to O’Gorman.

Part Three, ‘Tension’: May–September 1918

‘For what peace of mind can any man have if his honour is no longer in his own keeping?’

The Anatomy of Courage, by Lord Moran.

As I have explained, this is to do with ‘courage’ – and its opposite, ‘fear’ (that Platonic theory of opposites again). At this point in the book we find Phillip in a great state of ‘Tension’ as the section is headed. He is peculiarly and rather uncomprehendingly distraught. Although it is not made startlingly obvious, he is in fact in a state of nervous breakdown: as was HW at this point. And the quotation from Lord Moran is to point us in the direction of that thought. Once one grasps that, most of the obscurities become clear.

Phillip is taken to a hospital at Husborne Abbey, run by the Duchess of Gaultshire, where he gradually recovers his strength and his sight. But he is in a state of acute anxiety, blaming himself for Spectre’s death and certain that he is going to be reprimanded for this and court-martialled.

First, a word about the hospital, which was based on the real hospital at Woburn Abbey organised by the Duchess of Bedford. I recently investigated the background to this and find HW is correct in every tiny detail of description and the quite intimate detail of the regime, and indeed of the daily life of the Duchess, who herself worked tirelessly throughout the war – from scrubbing floors to qualifying as surgeon’s assistant (the article is not yet published but I hope will appear in the HWSJ in due course). This is quite amazing when one realises that HW himself did not spend any time in this hospital – and very few of the details he incorporates were in the public domain at the time he wrote this volume. There were many such hospitals run by aristocratic women – but the one at Woburn seems to have been especially superbly professional. Lady Mary was quite an extraordinary woman.

Meanwhile Hetty and her daughter Elizabeth go up into the City to watch a procession of the Women’s Land Army, which Doris has joined, incorporating yet another aspect of social history.

While recovering, Phillip is taken out for a ride in the pony and cart by a lady and a small girl: Lady Abeline and her five-year-old daughter Melissa. Introduced briefly here, Melissa is to play a prominent part in the later novels. Phillip also meets up again with Denis Sisley, with whom he becomes friendly.

The Duke sends for him – to his great trepidation, thinking he is going to be questioned about Spectre – but he turns out to be a reserved and awkward man who only comes alive when talking about birds. Phillip has heard an unusual cuckoo call and is able to draw the great man out on this topic. This is exactly how the then Duke of Bedford behaved. It is also revealed that the Duke (very sadly) does not get on with his only son, who is a conscientious objector: again, as in real life.

In due course Phillip has to endure (with great dread beforehand) a ‘senior officers’ meeting’ – an informal enquiry about Spectre West. He is convinced this is to do with his part and O’Gorman’s in Spectre’s death, and so he stalls the questions put to him. But everyone seems very understanding and nothing untoward happens. The reader realises that this meeting was not an ‘investigation’ in the sense Phillip thinks it is: the dread is all in his own mind. These senior officers are merely trying to get Colonel West honoured with a memorial plaque. But Phillip is as tense as ever. He goes up to London to get kitted out with new uniform.

It was June, it was high summer, nobody there heard the guns, nobody saw rifles thrown forward as ghosts left bodies sinking at the knees, heads falling forward upon ruined fields under the Monts de Flandres, or among old and rotting heaps of sandbags from which the chalk had long since broken, above the Somme and the Marne.

He is now sent to Falmouth in Cornwall to convalesce – setting off from Husborne Abbey in

one of half-dozen 1901 [Rolls Royce] Silver Ghost landaulettes to Bleachley junction [Bletchley – which was to be so important in the Second World War], with luncheon basket provided.

He is based at Tregaskis House. (This is Trefusis House: HW was actually there in the summer of 1917 and it was while there that he began to write. This was obviously a form of therapy recommended for the nervous state that he was in.) There is bathing, tennis and rowing, picnics and trips out to the Implacable, a warship from Nelson’s era, moored out in the harbour where they could dive off the deck into the water. There is a great deal of larking about with surreptitious drinking and smoking. Phillip makes friends with the Tregaskis sixteen-year-old twins and local shop assistants, Editha (Edie) and Beth Sithney (their real names).

|

| Henry and Edie, 1917 |

(For other photographs of Henry's time at Trefusis, see HW at Trefusis House page.)

The Times announces that Phillip has been awarded the DSO: but he just feels guilty that it was his fault that Spectre West died and wishes that he had drowned with him. (Note that HW did not receive a DSO in real life.) He gets drunk and causes a minor scandal by hiding under Edie’s bed, passing out and terrifying the poor girl. For this misdemeanour he is sent away from Tregaskis to Devonport Military Hospital (as was HW), where he meets ‘dear, delightful Gibbo’, who 'sometimes stuck on a Charlie Chaplin moustache, while wearing an eyeglass with his usual languid manner'.

It was a tremendous friendship, while it lasted; and it lasted all their lives – in Phillip’s memory.

It is not known whom ‘Gibbo’ was: presumably he was later killed in action – hence HW’s words here.

Phillip is given three weeks’ leave prior to returning to Landguard. Visiting the Moon Insurance Office (where he was a clerk before the war started) he enquires if Downham will be returning. If so, then he definitely will not, but on the new Norton motorcycle he has on order ‘would go down to the West Country and live alone in the woods’: the first intimation of his plan for his future life (as in real life).

After four days at home he returns to Landguard, where he is detailed to attend the Minden Day Celebration at Husborne (home of the Duke) with his Colonel, Lord Satchville. So he returns to the Abbey, no longer a patient but as soldier honoured with the DSO. Phillip finds the ceremony moving,

while his mind burned within ancient sunlight of Somme and Bullecourt, the Bull Ring at Étaples, the white chalk parapets of the Bird Cage, the brown desolation of the Messines Ridge. . . . And now it was ending, and he wanted it to go on, for ever and for ever, in the sunlight which was shining on the dead, in the spirit which carried all who had walked away from love at home and found a greater love in friendship of men like Father Aloysius in the land of pain and destruction.

The men wear roses and at dinner roses are eaten accompanied by a glass of champagne!

‘Minden Day’ celebrates the battle that took place on 1 August 1759 in the Seven Years War (1756-63) when Britain was allied with Prussia against France, Austria, Russia and Spain. HW’s actual diary records for 1 August 1918: ‘Linden Day. Tennis with Ld. Ampthill & two others.’

There was a ceremony within the Bedfordshire regiment which took place on that day each year – still celebrated by the Royal Anglian Regiment, into which the Bedfordshires were subsumed in 1964. HW seems to have taken the details of the Battle of Minden (1 August 1759) from his old Pears Encyclopedia and from those notes above.

Phillip returns to Landguard and routine work. He receives the command to attend Buckingham Palace for the investiture of his DSO by George V. He is further invited to shoot with the Duke by his Colonel, Lord Satchville. He goes to a gunsmith to buy himself a suitable gun and the necessary trappings. He doesn’t get tickets for his family for the investiture and they watch from the gates. Afterwards Colonel Vallum tells him, kindly, that men are wanted for the Indian Army (and he subsequently applies).

|

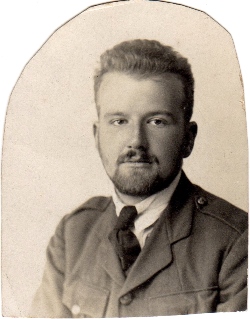

| HW's draft citation for Phillip's DSO |

Part Four, ‘The Lost Kingdom’

A man may bear a world’s contempt when he bears that within himself that says he is Worthy. When he contemns himself – there burns the Hell.

From a diary written at Sebastopol 1856

by Augustus Williamson, Lieut. 30th Foot.

The background to that quote has been explained. Phillip is still in a state of great disturbance, mainly because he is still ‘condemning’ himself for Spectre’s death. His guilt is an overwhelming burden. He feels himself to have been a coward, although the evidence suggests otherwise. He is of course in a state of shell-shock, which is manifesting itself in this rather strange behaviour.

Phillip cuts any celebration of his investiture with his family, and indeed with his regiment, and spends the evening with his friends Desmond and Eugene; he later meets a girl who picks him up and they end up sleeping together. Hiring a car, he attends the shooting party at Husborne Abbey where he sees young Melissa again, feeling he loves her. He forbears to call in to see his relations at neighbouring Beau Brickhill. Back at Landguard he is shocked to realise he has caught a venereal infection, seeks medical advice, and adds to his burden of unworthiness.

The news arrives that the tide has turned and the Allies are – with difficulty, but rapidly – forcing the Germans back. He asks to be sent back out but is told firmly that his application to be transferred to the Indian Army has been accepted and that he is to stand by.

Given embarkation leave, Phillip goes home but is recalled. His orders to stand by for Taranto (Italy) and onward to India are cancelled: officers are no longer required for the Indian Army. This scenario mirrors HW’s own: he was supposed to sail for India on 4 November, but this was cancelled (see AW, Henry Williamson and the First World War, p. 147). Then:

It was over. It was ended. He sat in his bedroom of No. 9, Manor Terrace, at noon on 11th November, and mourned alone, possessed by vacancy that soon the faces of the living would join those of the dead, and be known no more.

There is no sense of triumph here, just a dull and numb feeling that it was all over. HW’s actual diary recorded:

Armistice signed at 5.30 this morning. Bands playing, guns, sirens etc etc. PEACE!

A few days later Phillip, along with other colleagues, watches surrendered German submarines (Unterseeboot: ‘Undersea boat’ – ‘U-boat’) enter Harwich Harbour (across the estuary from Landguard Fort) in silence. Orders had been given that there was to be ‘No cheering’. All due respect to the vanquished must be maintained.

Not a movement among the crews, only the ribbons of their caps fluttering in the breeze; not a word from the onlookers as the U-boats went by in procession to surrender.

Such weariness; such sadness.

This was a real event witnessed by HW. (See HWSJ 43, September 2007, John Gregory, ‘The Great War in the Writings of Henry Williamson’, pp. 68-91, where there are several photographs of this event on pp. 89-90.)

It will be recollected that in his diary at the end of January 1959 HW had noted that he ‘must end the war by Chapter 4’: I would point out that we are now at chapter eighteen!

Phillip is asked to accompany Col. Lord Satchville to address disaffected troops at nearby Ipswich. Thus HW draws into his tale the problems that now arose as men found that, the war over, they were not wanted and no arrangements had been made to help them.

We learn here about the devastation caused by the Spanish Flu pandemic of 1918 that, taken right across Europe, killed as many civilians as the war had soldiers – and millions more around the world. Within the immediate circle of our novel it has killed Thomas Turney’s elderly sister, Marian, and he too is recovering from the illness, but is left considerably weakened.

Phillip decides to stay on in the army for a further year. His rank is substantiated to Captain and his pay will be 18s. 6d. a day. He is sent down to Folkestone (Kent) to help organise men returning from the Front. Here he meets Eve Fairfax, Mrs. Lionel Fairfax, with whom he has an affaire, unaware that he is only one of her admirers (of whom, indeed, his cousin Willie is one). He meets Julian Warbeck who actually lives near his family home, with whom he becomes friendly.

|

|

|

| 'Eve Fairfax' – Mabs Baker (aged 16) | 'Julian Warbeck' – Frank Davis |

|

|

HW, photographed by Mabs, on the steps of her house in Folkestone |

|

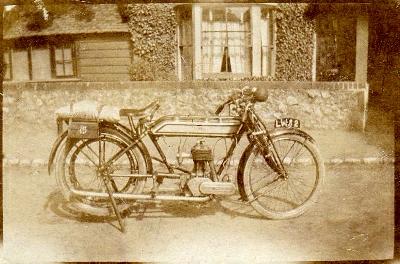

| More relaxed, HW on his Norton motorcycle LW82 |

|

|

LW82 - HW's new Norton Brooklands Road Special, his pride and joy |

He now buys a Norton Brooklands Road Special motorcycle and is able to get about the countryside in style. His sister Elizabeth, spending a holiday in Folkestone, spies on him and reports his ‘goings on’ to their mother. The ‘Folkestone scene’ is kept quite short here. It hinges back to the similar episode related in The Dream of Fair Women (1924), where we are told the tale in great detail from Willie Maddison’s point of view. Both Willie and Phillip are of course versions of HW himself. It all makes for fascinating reading!

(For the full background and true story of this era, see HWSJ 39, September 2003, AW, ‘Save His Own Soul He Hath No Star’, pp. 29-60; and the booklet Recreating a Lost World: Henry Williamson and Folkestone, 1919-20 (2008; e-book 2014, HWS)

Due to the problems arising from Phillip’s behaviour he is sent somewhat peremptorily to join his regiment at Cannock Chase, but he becomes extremely withdrawn, neglecting all regimental routine. The doctor he sees realises that he is suffering from depression (war-fatigue), and recommends a rest with some light reading. But very soon the CO sends for him and tells him he is to be demobilised forthwith.

Phillip (as did HW) rides out of camp and out of the army on his motorbike (in a manner strongly reminiscent of T. E. Lawrence, with whom HW was to become friendly in due course, on his leaving the Royal Air Force). He calls into Beau Brickhill with piercing result:

Phillip waited in shadow, hesitating whether to call out. Then he saw the thin figure of Grannie Thacker in the doorway, dressed in black as always, tight bodice over the wooden corsets which had been her mother’s before her, her skirts below the ankles of her button boots, her hair scrimped into a wispy nob.

Her voice called quietly. ‘Is that you, Percy?’

He stood still, alarmed lest he shock her. Had she waited, every moment, every hour, of all the days and nights since cousin Percy had been killed at Flers on the Somme: waiting for a miracle, sustained by hope in God’s goodness that Liz’s boy would one day come home?

He learns that cousin Polly is to be married to her cousin, a farmer. They also discuss Doris and her new beau, Bob Willoughby, but as Polly says, ‘although I think she will never forget Percy’. Phillip makes his way home.

Resting astride the Norton on the crest of the Sydenham ridge he looked north and saw the grammar school on the hill standing above a grey wilderness of roofs and church spires under the smoke of London. If only it were like Ypres, so that the rubble could be cleared away, and fields of grass and corn rise again; or even lie in ruins like the Cloth Hall, with grass growing on the ruined walls, and wild flowers, and willows, and strange birds returned to a wilderness sanctuary – then there might be hope. Where could he go, what could he do . . . was his longing to be forever like that of Edgar Allen Poe for Annabelle Lee in that lost kingdom by the sea?

Phillip is not looking forward to civvy street. He feels lost, and at a loss. He has no sense of direction.

(The reference to Edgar Allen Poe’s poem crops up again in a later volume where it has more import and will be discussed at that point. It is enough here to state the obvious that it is about loss. Here it is the loss of the life of comrades and comradeship, and of his youth which cannot be recaptured, of a world which is lost forever: ‘that lost kingdom’ – giving the title of this section.)

Part Five: ‘No-Man’s-Land In Civvy Street’

But the old flags reel and the old drums rattle

As once in my life they throbbed and reeled;

I have found my youth in the lost battle,

I have found my heart in the battlefield.

From A Song of Defeat, by G.K. Chesterton

[G.K. Chesterton (1874–1936) poet, novelist, journalist, essayist, who became a Roman Catholic in 1922.]

This poem was written in 1915, and it would appear that HW expected his readers to be familiar with the words (or was playing one of his games), for it is the lines fore and aft of those quoted that really hold the significance, matching the essential point of this section. Note the title here: ‘civvy street’ is a ‘no-man’s-land’ – a battle zone. Those lines ‘omitted’ are:

Earth will grow worse till men redeem it,

And wars more evil, ere all wars cease

[Then the lines quoted above, followed by:]

For we that fight till the earth is free,

We are not easy in victory.

That gives a much more direct context of the essence of the mood that HW imbues into the end of this volume, and with his own feelings (and those of many disillusioned ex-soldiers) after the war ended.

Phillip does not return to his pre-war job in the Moon Insurance Office, ostensibly on account of Downham’s return; but of course he had no intention of doing so. He loafs around at home to the general discontent of all. He meets up again with Julian Warbeck, who immediately reels off the list of lovers of ‘La Belle Amie’ (Eve Fairfax). Julian, lover and declaimer of the poetry of Swinburne, is in a very similar situation to Philip. (He is based on the badly shell-shocked Frank Davis, see references for Folkestone above.)

Phillip, with his mother and sister Doris, attend cousin Polly Pickering’s wedding to her cousin George Turney, again as in real life:

|

|

Wedding of Marjorie Boon to William Frank Turney, November 1919

Back row: William Turney (Frank's father), Gertrude Eliza Williamson, HW, Doris Mary (Biddy) Williamson, Will Turney, Henry Boon (bride's father; 'Uncle Jim' in ACAS) Front row: Emma Turney (Frank's mother; née Cooper, aunt of filmstar Gary Cooper), William Frank Turney (groom), Marjorie (Boon) Turney (bride), Nina Turney (daughter of Will in the back row), Margaret Elizabeth Boon (bride's mother; 'Aunt Lil' in ACAS), Ethel Boon (Henry Boon's sister) |

It is insinuated that this was not a totally happy occasion, and that no doubt reflects reality.

At home Phillip and his father do not get on. They have a huge argument over the war and the prevalent attitude to German soldiers, Richard still believing all and only what he read in his daily newspaper, which ends in Phillip being told to leave the house. As he trudges off over old haunts he is accompanied by the obnoxious Ching, who has wormed his way back into Phillip’s circle. But Ching is in a strange, excited, self-piteous state, and ends up setting fire to a workman’s hut. He runs off and it is Phillip who gets caught and taken to the police station and charged with arson. He sends a message to Mrs Neville, ever his confidant, and eventually also tells his grandfather what actually happened. Mr Turney in his turn tells Hetty, but they are sworn not to reveal this truth to Richard.

Phillip now moves into his Uncle Hugh’s old ‘garden’ room (well fumigated!) in his grandfather’s house next door.

It was the best dug-out he had ever had, he declared, and put a notice above the door

GARTENFESTE

[translates literally as 'Garden Castle' – Phillip thought of it as his 'Garden Strong-point'.]

At his court appearance Phillip pleads guilty, although advised not to: we learn that he is terrified that it will come out that O’Gorman had been ordered to remove his cork lifebelt which led to the death of Brigadier-General West. He is given a month in prison.

This is of course totally irrational. That episode has nothing whatsoever to do with his present situation, and there is almost certainly no way the present court could know of the supposed previous problem. What HW is doing here is showing the totally shocked state of mind, the extreme state of nervous tension, of breakdown, within Phillip and so reveals what was his own state at this period. It is a passage of great importance, and I suspect not understood or grasped by most readers. HW wraps everything up so cleverly, buries it all so deeply here in his writing, as he no doubt did in real life, that it passes us by.

On his release, Phillip wanders around his old haunts at night in the snow, remembering what it used to be like in his boyhood, the birds he used to see and the wilderness, and the emotions that nature conjures in us, so well described by Jefferies and poets. He reaches the Seven Fields (‘of Shroften’ - a place his father loved before his marriage).

His thoughts jump all over the place, from battlefield scenes to his parents. He knows he must apologise to his father. He feels Spectre West’s spirit is helping him. He goes into St Mary’s church and ‘with tears running down his face hidden in his hands as he prayed to be a better man'.

He returns to the home he has been forbidden to make his apology, but Richard will not listen and causes another quarrel. Phillip becomes hysterical, threatens to shoot himself, gets his gun and runs off, grabs Sprat from a distraught Mrs Neville, but later calms down and returns. His father, having been told the truth about the cause of the fire and rather shocked at the outburst he has caused, also calms down and the family rift is healed.

Phillip goes to see Eugene. While in Leicester Square he sees Bill Kidd standing outside the Picture Palace (where he is doorman), who says his assistant is O’Gorman, and reveals that O’Gorman thinks Phillip is a hero. He had never HAD a cork lifebelt (whereas Phillip has thought all this time – erroneously – that he had told O’Gorman ‘to leave all his gear’ with him on the ship and that was why the batman was not wearing it when he went to see if Spectre was all right). O’Gorman hadn’t bothered to put one on and Spectre therefore made him take his. O’Gorman thinks Phillip saved him from a court-martial by keeping quiet about this at the ‘officer’s enquiry’. So a huge burden is now lifted off Phillip, and freed from the guilt he has been feeling about Spectre, he can, at least, think in terms of the future. That particular boil has now been lanced.

One morning he read in the newspaper that a new Club for writers was to be formed in London, with premises in Long Acre, where once a week young authors and journalists might foregather to discuss literary matters and listen to lectures by famous writers.

This was The Tomorrow Club run by Mrs. Dawson Scott (Sappho), which HW joined at this time.

Phillip joins this ‘Parnassus Club’. He takes Julian Warbeck to a meeting, but Warbeck heckles the speaker and generally creates mayhem. Phillip decides to become a journalist in Fleet Street and his grandfather Thomas Turney gets him (through his connections in business) an introduction to Lord Castleton, where he obtains a job in the canvassing department under Major Pemberthy.

But Thomas Turney is failing rapidly, and he shortly dies (in a rather painful passage) and is buried in Randiswell Cemetery. At the reading of the Will we find Elizabeth revealing her avaricious nature. The diamond ring that had been promised to his son Charlie cannot be found (and this is to cause future trouble). Maudie, the sole remaining member of the Cakebread family (other than Ralph, disinherited after he became a Mormon) gets her mother’s share of £8,000. Hetty is left his house (next door) and her share of the residual estate.

Phillip escorts Maudie back to the railway station, telling her he is going to be a writer and that he feels:

a sense of power with which to face the future, because now he understood what had not always been clear in the past. No man could be destroyed, once he had discovered poetry, the spirit of life.

On which optimistic note, this volume ends.

*************************

Index and Chronology to A Test to Destruction: Maps and Chronology and Index

Between 2000 and 2002 Peter Lewis, a longstanding and dedicated member of The Henry Williamson Society, researched and prepared indices of the individual books in the Chronicle of Ancient Sunlight series (the first three volumes being indexed together as 'The London Trilogy'). Originally typed by hand, copies were given only to a select few. His index to A Test to Destruction is reproduced here in a non-searchable PDF format, in two parts, with his kind permission. It forms a valuable and, indeed, unique resource. Copyrighted maps and the synopsis are not included here.

*************************

Click on link to go to Critical reception.

*************************

The dust wrapper of the first edition, Macdonald, 1960 – HW very much wanted to use the etching of three soldiers that C. R. W. Nevinson had given him (a preparatory treatment for his painting 'A Group of Soldiers'); see HW's correspondence with Macdonald on the subject. In the event Macdonald went their own way, and the etching was instead used very effectively on the back cover. The design of the cover is unattributed, but is so unlike James Broom Lynne's previous and later wrappers for the Chronicle that it seems unlikely that he was responsible.

Other editions:

|

|

|

| Panther, paperback, 1964; and back cover | ||

|

| Chivers Press, hardback, 1980 |

|

|

|

| Macdonald, hardback, 1985 |

Sutton, paperback, 1997 |

Back to 'A Life's Work' Back to 'Love and the Loveless' Forward to 'The Innocent Moon'