ON FOOT IN DEVON

or

Guidance and Gossip

being a Monologue in Two Reels

|

|

| Alexander MacLehose, 1933 |

Alexander MacLehose & Co., June 1933, 5 shillings

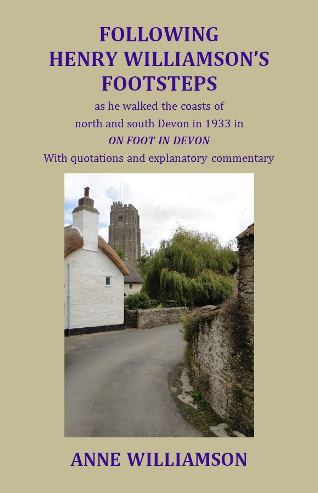

Cover illustration by C. F. Tunnicliffe

With 8 illustrations (photographs of scenes mentioned in the book)

Dedication:

‘To Miss A. T. who did all the work.’

(Ann – or Myfanwy, as she later preferred to be known – Thomas, was the daughter of the poet Edward Thomas and HW’s secretary since late 1931.)

Matthews (Henry Williamson: A Bibliography, 2004) states that a series of different binding colours, blurbs and prices indicate that the book was reprinted several times, but there is no factual information in the archive to support this.

The book was printed by Robert MacLehose & Co. Ltd, The University Press, Glasgow: the prestigious firm which had previously printed the limited edition of Linhay on the Downs in 1929. I have found it difficult to discover any facts about this printer – it has proved even more difficult to find any information about Alexander MacLehose's publishing business. They are obviously of the same family.

With regard to the look of this small volume, particularly of note are the rounded corners of the cover, which would have made it an easy book to slip into the pocket when walking (presumably a feature of the series). One hopes though that the Tunnicliffe dust wrapper (without rounded corners!) was first removed.

This simple short book has an extraordinarily complicated background that reveals the chaos at this time in HW’s personal life and business dealings.

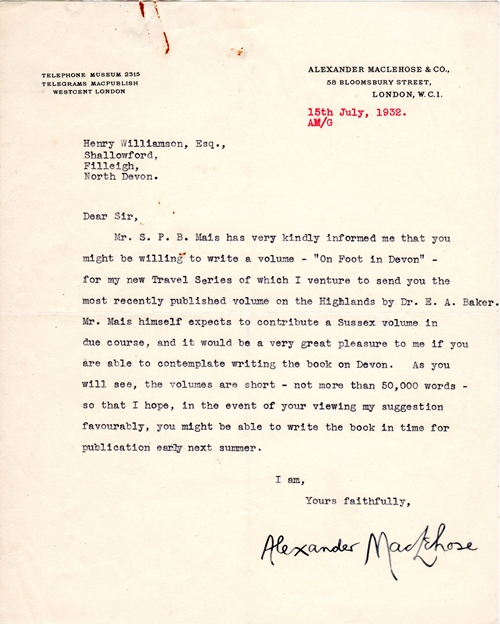

It started well. In the summer of 1932 HW’s friend S. P. B. (‘Petre’) Mais, a prolific writer of novels and travel books (see Robert Walker, ‘S. P. B. Mais – Henry’s longest Literary Relationship’, HWSJ 49, September 2013, pp. 35-53) suggested that HW should write the Devon volume for the ‘On Foot’ series being published by Alexander MacLehose, as is seen from MacLehose’s opening letter, dated 15 July 1932:

HW agreed, but on condition it was understood that his book would not be a normal ‘travel book’ but his personal response to the area limited to the North Devon coast, which he knew well, plus part of the south coast. MacLehose replied that he was delighted. HW then haggled over the financial terms, asking for more than MacLehose suggested. MacLehose stuck to his guns, and delivery of the manuscript was agreed for 1 February 1933.

In early December 1932 MacLehose wrote asking for a synopsis of the proposed work for inclusion in his catalogue of forthcoming books. Ann Thomas replied stating that HW was very busy, but it was all in hand for the 1 February deadline. So begins what was to turn into a convoluted contretemps!

HW was indeed at this time very busy. The Star-born (May 1933) and The Gold Falcon (February 1933) were in the process of publication, the latter with considerable attendant chaos, especially with regard to the USA edition (not yet fixed up), combined with HW’s insistence on total secrecy regarding its author. There were also new editions of previous titles at this time, notably The Old Stag (Putnam, March 1933, 5/-) ‘revised and containing several new stories with woodcuts and decorations by C. F. Tunnicliffe’; and later in the year a similar treatment for The Lone Swallows, adding the title to the uniform illustrated edition.

In January MacLehose wrote again asking for a short description, of about ‘150’ words. Ann Thomas’s reply included a synopsis, and also stated that HW wanted to provide at least two dozen photographs, far more than was usual in the series. In the event he provided none; eight stock photographs were used, taken from the photographic catalogue of Judges’ Ltd, a well-known company specialising in photographing and producing postcards of British landscapes. The synopsis reads:

A personal account of many walks through Devon – along the north coast by the Severn Sea from the Somersetshire border, down the Atlantic coast to the beginning of Cornwall; wanderings on Exmoor by Dunkery and the high hills, and along the marshy banks of the river Barle; and over the great range of the high downs to the valleys of the Taw and Torridge, and all the way up to Dartmoor and its lonely green wastes of enchantment. Three friends, whose peregrinations this book describes, provide a dialogue which is a commentary on themselves as well as on the scenes they pass. One is a visiting American, the second is a native Devonian, and the third is a visitor who has made Devon his home. The result is a lively book, and one full of the sort of information that is not usually found in more orthodox guidebooks.

This synopsis included elements not really applicable to the finished book, as will be revealed; but the main problem was that with the agreed 1 February deadline looming, not a word had actually been written, despite Ann’s assurances.

(Fuller details about this background can be found in Anne Williamson, [‘Background to] On Foot In Devon’, HWSJ 46, September 2010, pp. 34-42: where unfortunately the words ‘Background to’ in the title were omitted. Also unfortunately, inserted in the middle of this article is information about HW’s route & map for Reel II, South Devon, which really applies to other articles printed later in that issue, making a bit of a muddle.)

But HW was now galvanised into action, and on 13 January he and Ann took a train to Lynton and commenced the first leg of this mini-odyssey. The following day HW and his wife Gipsy went to Hartland and walked there. Thus the start and finish of the North Devon coast section. HW began dictating the book to Ann at the rate of three to four thousand words a day. On 29 January Ann noted in the diary that the book was finished. She would then have begun typing up a fair copy.

On 31 January HW learned of the death of John Galsworthy. HW and Gipsy went up to London for the funeral, where he stayed with Richard de la Mare (his friend, best man, and currently publisher of The Gold Falcon). HW took with him The Star-born material for Faber (i.e. for Richard de la Mare), the first two typed-up chapters of On Foot in Devon – and, significantly, the MacLehose contract.

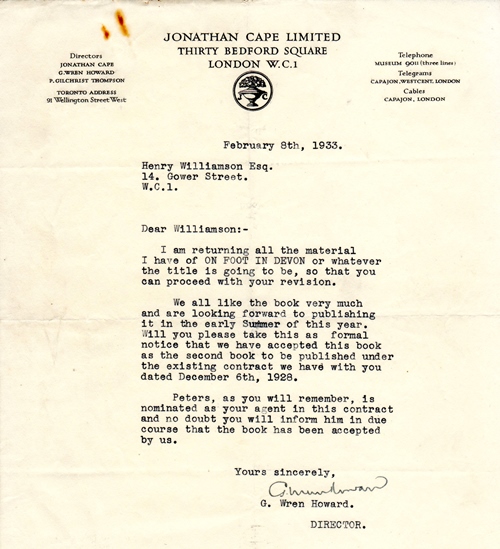

‘Significantly’: for a huge problem, not actually mentioned anywhere in HW’s private papers, is now revealed. HW was actually under contract to Jonathan Cape for his next three books: and so the material for On Foot in Devon was technically and legally theirs. HW obviously showed his material to Cape. (It is quite difficult to piece all this together, for while HW was in London his diary was still with Ann at Shallowford, so there are no diary entries regarding the matter. Mainly the information is gleaned from the various business letters extant – but much of this was dealt with in face to face conversations and by telephone.) Cape wrote a confirming letter showing they liked the book and confirming that the rights did indeed belong to them.

HW now informed MacLehose by telephone that he had handed the book over to Cape. Whereupon MacLehose pointed out that he had not previously been made aware of any such problem and that the book had been promised to him, was under contract, and must go ahead.

HW was now in quite a panic, though unusually for him, and no doubt on the advice of Dick de la Mare, he seems to have been placatory, apparently asking MacLehose for time to revise his overlong manuscript. He had, however, secretly decided to let Cape keep the current typescript and to produce another for MacLehose within a month. He and Gipsy returned to Devon.

Because he was re-writing the book, the blurb used on the dustwrapper, already written, brought about its own complications, as HW's note below illustrates:

The proof of the dust wrapper shows HW's revisions to the blurb; in the event a completely different blurb was used anyway:

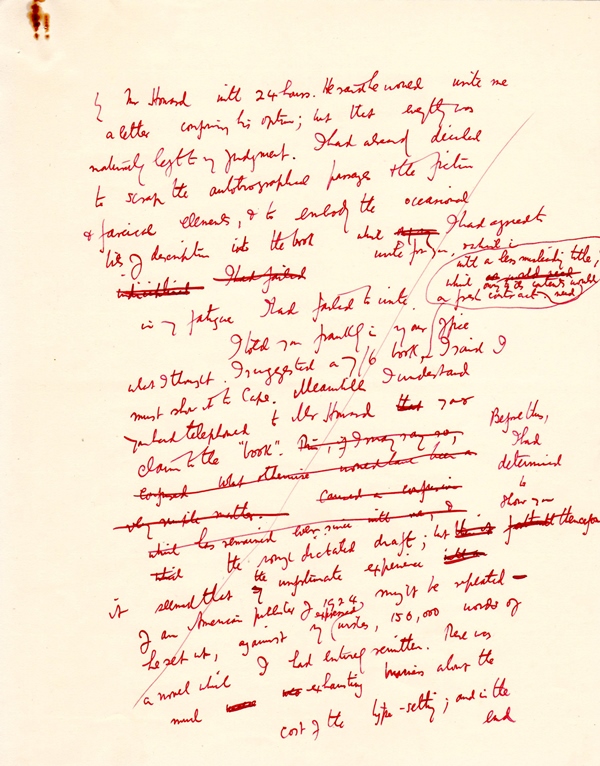

However, Alexander MacLehose now contacted Cape direct and so learned the full story. Although he must have been incensed, his letters are very calm. He wrote that (on default of the book itself) he was prepared to destroy their contract, providing HW returned the £50 advance already paid, plus £20 for expenses involved. He added further that if HW did not meet one or other of these proposals, then he would have to take legal action. HW realised he had no choice (presumably he had spent the advance already, and was in no position to return such a large sum of money), and he agreed indeed to give the On Foot in Devon material to MacLehose, but asked for more time. MacLehose insisted on a signed letter to this effect. He also insisted that any similar book to be published by Cape must not appear for at least six months after his own book. Unfortunately, HW’s reply was sent off by Ann without his signature, evincing further panic, as is evident from the two draft letters he scrawled in red ink that survive in the archive:

The first 3-page draft letter (both were written on the same day, 16 February 1933):

Having read through what he had written, HW then revised the letter to this version (though whether it was then typed, signed, and posted is not known):

HW now had to eat humble pie with Cape. It was all resolved in the end, but did nothing to endear HW to these publishers. HW fulfilled his commitment to Cape in due course, and after a decent interval Devon Holiday was published by them in 1935. This book contains a great deal of the material from his original idea. I feel that these two books – Devon Holiday and On Foot in Devon – should really be considered as complementary to each other – a duo which between them do cover a walking tour of Devon; though ‘travel books’ they are not!

Chaos also reigned in HW’s own private life. Early in 1933 Gipsy had informed him that she was pregnant with their third child. Soon afterwards Ann Thomas informed him that she was also pregnant. This made life at Shallowford awkward to say the least. HW eventually arranged for Ann to stay with his younger sister Biddy (Doris), whose husband had now left her with two young boys to bring up: he gave Biddy sums of money quite regulary to supplement her income, and now he paid for Ann’s lodging, so helping both women.. For the time being, though, Ann remained at Shallowford, carrying out essential secretarial duties.

HW did not restart work on this book immediately. Ann wrote to say he had ’flu and congested lungs. One suspects he was mainly exhausted from this emotional see-saw of work and personal problems. But on 21 March he recorded: ‘Set off today on my S. Coast walk, reluctantly and a little fearfully.’

He went to Exeter, visiting the cathedral there, and the next day took the train to Sidmouth; from there he walked to Exmouth and continued. On 24 March he took the train to Plymouth where he hoped to meet up with ‘T. E. Shaw’ (T. E. Lawrence), then stationed at Mount Batten in Plymouth, but TEL had left just before he arrived. HW returned home the following day.

He went back to finish ‘Walking for On Foot’ on 26 April: where, at Torcross he records he met ‘a lovely girl, Ann Edmonds’, with whom he fell instantly in love, recording that night: ‘Melancholy, oh damned lonely and loveless and death-haunted’. Two days later, on 28 April, he returned to Shallowford.

HW’s diary entry for Tuesday, 9 May 1933 reads: ‘Finished the bloody book On Foot in Hell for MacLehose at 11.35am this day. Now for some real work – carpentry, dams, tomatoes, etc.’

On 17 May he recorded: ‘£50/-/- from MacLehose, advance for the bloodiest guide book’. (This was the second advance payment.)

Proofs had been dealt with by 26 May. Actual publication is not mentioned, but it was on 19 June, as mentioned in a review. Further letters from MacLehose reveal that there was an offer for an American edition, but HW prevaricated and so it appears to have been dropped – though he has written a huge scrawling ‘YES’ against the last letter (March 1934) that mentions this.

With this letter was enclosed a Royalty statement. It states that 1392 copies had been sold to date. At the agreed royalty of 12½% this equals about £43/0/0d.

Thus HW’s advance of £100 had not been even half met. Neither would he really have even covered his own travel expenses, while MacLehose would seem to have lost considerably on the deal. This does not tally with Matthews’ suggestion of several printings. Perhaps there was a late surge in sales? Reviews were good as will be seen.

As an amusing aside, many years later a collector bought a secondhand copy of the book very cheaply because, the bookseller explained, the inside rear cover had been defaced, probably by a child in view of the spelling, in this way:

|

| (Image provided courtesy of Ted Wood) |

The collector was of the same opinion as the bookseller, until Richard Williamson, on seeing it, promptly identified the handwriting as his father's!

On Foot in Devon is told in two sections: REEL I (the north coast) and REEL II (the south coast), as is shown by the ‘Contents’ and the maps.

|

|

REEL I starts (after travelling from Barnstaple) at Lynmouth and, travelling west along the North Devon coast, ends more or less at the border (HW’s term) with Cornwall. (One is left feeling that to cross the boundary is to step into a foreign country!) REEL II, having taken the train to Exeter, and another down to Sidmouth, travels west along the South Devon coast to Salcombe. REEL I is about 24,000 words; REEL II about 26,000. HW kept to the original stipulated 50,000 words as closely as he could!

These are not ordinary walks, however (even allowing for the fact that they actually involved a fair amount of train and bus travel!). They are more musings through the thoughts and life of the walker that arise as he almost randomly meanders along. We meet many of his friends and learn a lot about his life and its likes and dislikes. It is a form of ‘stream of consciousness’ writing. It is certainly not the usual kind of travel book – but HW is quite honest about that. He tells his readers that it is a ‘Guidance and Gossip . . . a monologue in two reels’. (There is a distinct connotation of ‘film’ suggested by the word ‘reels’ – and indeed of ‘fishing’, for he was then very involved in re-stocking the river Bray, preparatory for the eventual book Salar the Salmon.)

HW’s writing skill is apparent: he paints a picture for us with every new scene. We are there with him and we partake in his journey. But there is also a big problem. Many of the people he mentions, their books, their ideas, are somewhat cryptic; thrown out in passing. They were probably a little obscure even at the time of publication – and they certainly are to the modern reader, for many of them are lost in the mists of time rather than seen in clear ‘Ancient Sunlight’. Despite this, they make a rich tapestry which reveals a pattern of life pertaining in Devon at that time, caught in a series of verbal photographs. HW rather expects the reader to know what he knew – or take the trouble to find out.

It is a detective story with a difference; a crossword puzzle in which the reader has to decipher the clues for himself. Perseverance does uncover the richness of this tapestry, but that requires time and effort, and a knowledge of where to look.

I have prepared a much more detailed explanatory commentary on On Foot in Devon, Following Henry Williamson’s Footsteps (HWS, e-book 2015); too lengthy to be included as a part of this summary, it has been published separately as an e-book. Meanwhile I will try and convey a brief flavour of the delights of this ‘entertainment’ – for that is what it is.

REEL I: The North Coast of Devon

The book opens:

One winter morning we two stood on Barnstaple station, waiting to travel to Lynton by the quaint miniature railway, stamping our feet and watching the gulls as they screamed and wheeled about the froth of the tide. . . .

Steam was hissing out of the safety valve of the little Lynton engine, a curious flat structure of brass and green paint on wheels.

The engine driver smiled and wished us good morning. It was time to get aboard.

The gauge of the railway was less than a yard, and the carriages held only eight people. Some of them consisted of a single bench, holding but four, and into one of these we got.

‘We two’ are HW and Ann Thomas. The date was 13 January 1933. This Barnstaple station was on the north side of the River Taw and served the Great Western Railway line from London via Taunton and also the line to Ilfracombe, as well as the narrow gauge line to Lynton put into place by Sir George Newnes. The station no longer exists – the current station is on the south side of the river where the ‘Tarka Line’ runs to Exeter (its name a great tribute to HW and his most famous book).

HW knew this amazing little railway well and wrote about it in various books. (For background see Peter Lewis, ‘The Lynton and Barnstaple Railway’, HWSJ 32, September 1996, pp. 24-34.) On this occasion HW did not actually start at Barnstaple: his home at Shallowford was well to the east. His diary notes that they motored north to Blackmoor Gate (well over half-way) and took the train from there. No matter: he had taken this journey on many occasions. The whole of the first chapter, 10 pages, describes the journey: a charming evocation of this eccentric line and the random (wide-ranging and haphazard) thoughts it induced in our traveller. HW is already introducing names of various people – friends, writers – whom he has known or who have associations with places he passes, and he continues to do so throughout the book.

A flavour of Lynton and Lynmouth is given together with the River Lyn, that seemingly benign stream tumbling down from Exmoor to the sea, which was to play such an important role in The Gale of the World, the last volume of his A Chronicle of Ancient Sunlight – still thirty or so years in the future. There is the merest hint about Shelley (Percy Bysshe, the poet), which hides a story in itself; a mention of Hollerday House, home of Sir George Newnes, burned down and now in ruins, again to appear in the later Chronicle; and then on ‘over the hills and away’ following the coastal route westwards.

Our author meets John (‘Jan’) Mills-Whitham, author and friend of HW, who is given a succinct verbal portrait but needs further notes to fully flesh him out.

Then we jump, as if on a magic carpet, to Challacombe, a tiny hamlet up on the road which crosses Exmoor. I suspect original readers must have been somewhat confused, but as you were told earlier, HW had left his car at Blackmoor Gate: Challacombe, a little way east, is on the road crossing the moor, and on an alternative route back to Shallowford at the end of that first day’s walk! He now walks up on to Exmoor proper, to Pinkworthy (‘Pinkery’) Pond and the Chains beyond. This was actually one of his favourite walks and one he often took – though he tended to be nervous about the bogs if one strayed off the path. (Today there is a well-laid path to take you there.)

Miraculously back on the coastal path he walks from ‘Koo Mart’n’ (Combe Martin). Here we meet a verbal tirade against the nineteenth-century naturalist father of Edmund Gosse ‘the celebrated acidulated literary critic’, whom HW definitely does not like. (Following Henry Williamson’s Footsteps expands on this.)

HW now introduces imaginary companions – caricatures of the type of people he particularly disliked – and chief of these is the disapproving Mrs Ramrod. This allows him to include a vein of satirical humour to leaven the way.

They continue, quoting ‘The Gallows’, a poem by Edward Thomas, as they pass a gamekeeper’s gallows. The import of this would not have been known to original readers, but as you now know the ‘female Scribe’ of the party is the poet’s daughter.

Mrs Ramrod falls off the dangerous well-known landmark of Bull Point, every bone broken on the rocks below, because she did not heed the author’s advice to keep well back!

We come to the equally dangerous headland known as Morte Point – where we are treated to a (typically HW) tale about a peregrine falcon and a raven. Morte Point in bad winter weather is a ferocious place. While our author drinks a shandy in the ‘Chichester Arms’ he sends his party off to look at the church. Walking on down to Woolacombe there is probably the most irritatingly oblique mention in the whole book: ‘a young painter who won the Prix de Rome’. With some difficulty I have discovered who this was: it is revealed in Following Henry Williamson’s Footsteps (to be equally irritating!).

Now we are down on to Woolacombe Sands, where we are advised to walk barefoot, as should all ‘statesmen and others in places of responsibility. Then the spirit of earth arises into one’s being . . .’

We are also told to look out for a particular tall black funnel that will appear around Morte Point at ‘3 o’clock’. This was the redoubtable little tramp steamer Snowflake, which plied between Swansea (far across the Severn Sea) and Combe Martin. Alas – to be seen no more!

(The Hele Bay website expands on the above caption – our thanks to John Moore for his permission to use this: 'A familiar sight along the coast between Combe Martin and Ilfracombe, was the Snowflake, a steam powered Clyde Puffer; a class of boat constructed with a vertical boiler, to save on length, for navigating the Scottish canals. She was built in Glasgow in 1893 as the Maid of Lorn and was registered as 73.3 tons with a length of 66' (the maximum that could fit into the locks). She was wrecked off Iona in 1896, repaired, and sold to flour merchants Hoskin, Trevithick and Polkinhorne in Hayle, Cornwall, who renamed her Snowflake after their brand of flour. She proved too small for their needs and was sold to the Irwin family of Combe Martin in 1897. For the next 50 years she carried coal, building materials and even fresh produce, such as Combe Martin strawberries, along and across the Bristol Channel. She went ashore at Lester Point in 1912 and it is said that after a visit to Hele in the 1920s, when she was holed, she used Larkstone Beach for coal deliveries instead. She hit a rock off Little Hangman in 1936 and was beached in Watermouth Cove. Her Captain then, James Irwin, is said to have remarked "I know every rock in the Bristol Channel; and that was one of them". She was sold by the Irwins in 1940 but remained in the area, working as a water supply boat for the Armed Forces, until she went to the Greek Islands in 1946. She was beached in 1953 in Piraeus but was still registered, in the former Yugoslavia, in the 1960s.')

So HW continues his idiosyncratic tale. We learn how in 1919 he had got his beloved Norton motorcycle stuck on the sands. Then follows a justifiable rant about litter: it was his habit throughout his life to gather up this foul detritus and set fire to it on the beach. He also mentions ‘Black Rock’ – more or less the demarcation point between Woolacombe Sands and Putsborough Beach – but refrains from telling the world that this is the point at which he would arrive on the beach having walked down from his own Field and Writing Hut at Ox’s Cross.

However he does detour inland to Georgeham, singing the praises of both the King’s Arms and the Rock Inn (his often described fictional ‘Upper and Lower Houses’). We learn sometime later that here his little troupe of strollers was joined by an American Professor. This was Professor Herbert Faulkner West, whom HW had met in early 1931 while on his visit to America, when he lectured at Dartmouth College. In 1932, while on a visit to England, the professor had visited HW at Shallowford and published a charming essay, The Dreamer of Devon. (He was not, of course, actually on this walk.)

HW’s route now goes to Braunton Burrows, the expanse of sand hills that feature so often in his work, where there is a nodding glance at R. D. Blackmore’s Maid of Sker, and his own The Pathway. Then on to Airey Point where one used to be able to hail a salmon boat to be ferried across the estuary, as mentioned so often in HW’s writings. This is no longer possible, and one now has to keep on round the north bank of the River Taw to Barnstaple.

The route to Barnstaple takes in the superb writer ‘Saki’ (H. H. Munro, killed in action in the First World War) and HW’s own friend ‘Kit’ Williams, composer of an organ piece The Wet Flanders Plain (which title HW used for his story of a return visit to the battlefields), but also a skier and author of The High Pyrenees. HW had taken a skiing holiday with Kit in January 1929. He portrays him as ‘Becket Scrimgeour’ in the later A Chronicle of Ancient Sunlight.

|

| Kit Williams in the late 1920s |

But HW has tricked us and has indeed crossed over the estuary to arrive at Appledore, and then on to the famous Pebble Ridge of Westward Ho!, which Rudyard Kipling made famous in his book Stalky & Co.

Then on to Bideford by way of Abbotsham (which would be rather a detour actually! The Hibbert family had lived at Abbotsham for many years before moving to Landcross). That HW is very fond of the striking architectural form of Bideford Long Bridge is obvious. His best description of it appears in Tarka the Otter. More literary figures are invoked, including cryptic reference to John Gay, citizen of the town (see Following Henry Williamson’s Footsteps for details).

Trying to follow HW’s route instructions exactly is an almost certain recipe for getting lost, especially as at this point he crosses fields and follows hedgerows. Far better to follow a modern Ordnance Survey map and the Coastal Path markers – stopping to read On Foot in Devon at appropriate intervals! HW now gets into full stride (on a bus) on the way to Hartland, taking in the steep cliff-side fishing village of Clovelly en route (nowadays very tourist-orientated but still a pleasant experience), and continuing to mention various writers and their works: the famous John Galsworthy, whose family originated from the area (and now known to have actually been related to HW, unknown to either of them), and the lesser known John Lane, co-founder of the respected Bodley Head publishing company.

So on to Hartland: first the parish church (throwing in Mr. R. Pearse Chope and his book Farthest from Railways for good measure; again, recourse to my Following Henry Williamson’s Footsteps will explain all), and then the historical Abbey which dominates the area. After this diversion, we go on to ‘the country of the waterfalls’, where HW waxes lyrical about the view:

We saw headland after headland looming blue, one behind and above or below the other, far away into the mists and seas of Lyonesse, and all along the perilous coast the Atlantic rollers came in slowly and broke and flung up their slow white masses of spray.

‘Lyonesse’ is of course Tennyson’s King Arthur country in Cornwall; the phrase ‘slowly and broke’ is reminiscent of Tarka the Otter. And so they trudge on to that intangible border between the counties, which the American Professor crosses alone – the others mysteriously steal away, as in a dream-world.

REEL II: The South Coast of Devon

The mood and mode of Reel II is very different. HW arrives at Exeter alone in mid-March – indeed on 21 March, the Spring Equinox. He describes the city – in 1933 – as busy and crowded. He states that he has 90 minutes in which to explore this metropolis. (In actual fact he stayed overnight, continuing the next day, but the short timescale here gives a little drama to the tale.)

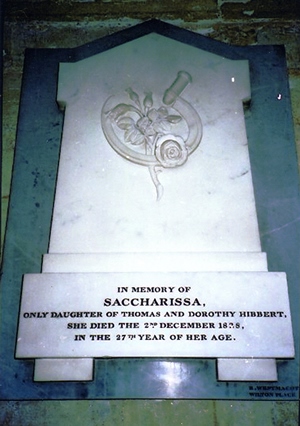

He ruminates on Rougemont Castle with its walls of red stone, emphasising that one must look for oneself and not just rely on guidebooks. But his actual objective is the Cathedral, where he points out various items of interest (discussed in Following Henry Williamson’s Footsteps), and particularly the beautiful marble memorial, carved with a sickle cutting a perfect rose, to Saccharissa Hibbert, who died 2 December 1828 aged twenty-seven.

This memorial was obviously very special to HW. Thirty years later he transposed it as that of Barley, the young first wife of Phillip Maddison, who dies tragically in childbirth in his novel It Was The Nightingale (Vol. 10 of A Chronicle of Ancient Sunlight, 1962). Saccharissa shared ancestry with HW’s actual first wife, Ida Loetitia Hibbert.

As he leaves the cathedral we meet the very eccentric Lord Bishop of Exeter, obviously a very well-known figure at that time, wheeling a bicycle. We also learn about the Courtenay family, once important landowners in that area. But today all these details need further explanation.

HW now takes a train to Sidmouth, first eastwards then changing on to the branch line south, and following the course of the River Otter, another benign river with an occasional savage bite. Sidmouth is ‘a pleasant little place’, but with a dangerous promenade liable to be undermined by a heavy sea (as still happens).

Proceeding westwards on his way up Sidmouth Hill, HW mentions ‘a wedding dress’ which had been made at Sidmouth. Even readers in 1933 would not have known that his wife’s uncle and family had lived in Sidmouth, and that she had stayed with them while her wedding dress was made and that the two daughters – Gipsy’s cousins – had been bridesmaids!

From this he moves on to a tale about his friend S. P. B. Mais, the prolific author who had proposed HW’s name for this book, being once caught out throwing away litter – a banana skin. Such is the banter between these two! As he continues westward HW whiles away the time with a tale on agricultural methods, describing scenes long vanished, until he finally arrives at Exmouth on the east side of the River Exe.

The next day he crosses the Exe estuary, involving a charming tale about a fisherman and his dog, to meet with friends: not named here, but an earlier diary entry reveals their name; and in following that up I discovered a most extraordinary connection with HW’s earlier book The Dream of Fair Women, far too complicated to go into here, I’m afraid, but again explained in Following Henry Williamson’s Footsteps.

As he crosses the estuary HW also mentions a book by Stephen Crane, Open Boat, which graphically describes a ship-wreck. Apart from the obvious plug for this readable but today long-forgotten book, the connotation obviously seized our author’s imagination; but his little journey in an open fishing boat is luckily without drama. He lands safely on Warren Sands on the south-west side of the Exe estuary.

There is now another cryptic reference: to Annie Rawle and her famous strain of Jack Russell terriers. Annie Rawle was employed at that time as HW’s housekeeper. She had previously worked for Arthur Heinemann (related to the Heinemann publishing family), who had bred these famous ‘Parson Jack Russell terriers’. It is thought by many that she must have known the breeding secrets of these dogs – but she did not impart them to HW!

So HW continues, past Dawlish with its decorative sculptured stream of tiered weirs. Looking out to sea, HW noticed a rock, standing up like

the last Victorian lady petrified but facing courageously the tides of change.

He then states that this was the ‘Old Maid rock’, but later, just to confuse the issue, decides it was actually the rock known as ‘Parson and Clerk’.

At Teignmouth (make sure you pronounce ‘Teign’ as ‘Tin’!) he takes the train which runs due west along the north side of the estuary to Newton Abbott. It is a charming stretch of water-views, but HW is not impressed:

During the journey of a half-dozen miles, I stared at the tide ebbing in its channels past the banks of mud and sand.

Arriving at Newton Abbot, again he is unimpressed, and resorts (so he states!) to a description from an old guide book. However he remembers that he has an aunt living there:

I spent ten minutes with my aunt whom I had not seen for ten years, and hurried back to catch the train to Torquay.

This aunt is Mary Leopoldina Williamson, who had taken such an interest in HW in his younger years and who is portrayed as Theodora Maddison, a key character in the Chronicle of Ancient Sunlight novels (where at this equivalent point in time, 1933, the fictional Theodora is living in Lynmouth).

Back on the train and further depressed by the thought of Torquay, he is cheered up by the arrival of ‘a spate of schoolgirls’ crowding into his carriage. We are given a hilarious description of their behaviour, including exchange of lipstick and rouge, and general mincingly flirtatious behaviour: quite a bevy of modern little minxes in fact – so young, and in 1933!

Having avoided a walk through the streets of Torquay, HW leaves the train at Paignton, promising to see the girls at Brixham (but he never does). But he soon gets fed up with walking and catches a bus to Brixham. After dinner he goes to see a film, previously seen in New York (which he had visited over the winter of 1930-1). Tantalisingly we are not told the title of this film: neither does the anecdote add to any sense of place in this tale.

The next morning he goes down to the fish market. This is one of the best passages in the book, a vivid word-picture of a busy scene full of genuine details: the reader is there.

Other auctions started. Crabs, lobsters (looking very small), Pollack, rays (called ‘thornbacks’ in North Devon, otherwise skates), halibut, soles, and heaps of dogfish. . . . Gulls screamed and blaked in the mud, or, perched on truck and bowsprit, relaxed drowsily content. . . . The walker lingered, loth to leave this scene of activity and interest.

Our author asks the fishermen if they have heard of the books of Stephen Reynolds, or perhaps have known the man himself. They shake their heads. Another cryptic reference not explained, and meaningless today without research. Stephen Reynolds had actually lived in Sidmouth and had worked for the Inspector of Fisheries. As an ardent and caring socialist he had written a book about poor fisher-folk. He had advocated Fishing Unions and was known as the ‘fisherman’s friend’. However he had died in the Spanish ’flu pandemic of 1919, aged only 38. I suspect HW thought of him as someone akin to Richard Jefferies.

We do learn however of a little snippet of history: the fact that William of Orange had landed at Brixham on 5 November 1688, when he arrived in Britain en route to London and the crown of England. We further learn here, as HW climbs the hill out of Brixham, that the lovely hymn 'Abide with me' was composed on Berry Head, the western promontory overlooking the town.

Brixham, with its diverse claims to fame, obviously impressed HW. But after more self-mesmerising thought, he realises he has eighteen miles to walk that day – eight to Kingswear, his next stop. Nothing, he states, to a man who had once walked over the Pyrenees from Laruns to Argèles in the time of avalanches. (The full tale of this not totally true adventure is related in later books.) He has to be in Kingswear to catch a train from Totnes to Plymouth,

where on the R.A.F. slip of Mount Batten I hoped to meet a friend that evening.

That is a cryptic clue to the fact that he was planning to meet up with ‘T. E. Shaw’ (T. E. Lawrence – Lawrence of Arabia), then stationed at Mount Batten.

Now, managing to get hopelessly lost and telling a hilarious tale combining cats and babies, he continues. The walking is rough and he stops to sort out a blister, then continues on his nonchalant way, telling us more or less what can be found and seen on the way until he arrives at Kingswear. Here he takes a ferry over to Dartmouth to get a (poor ‘cork-lino’) lunch, then returns. (The train only ran on this eastern side of the river.)

Feeling fed-up (literally on ‘cork-lino’), he merely ends this chapter: ‘The rhythm was broken, and I went by train.’ We hear no more of any visit to a friend at Mount Batten. But HW did make that journey, only to find when he got there that TEL was away and so his extra journey was in vain. At that point he did indeed return by train to Barnstaple, and so back to Shallowford.

The next chapter opens: ‘Some weeks later I returned to Kingswear.’ This was actually on Wednesday, 26 April 1933. Again crossing over the estuary to Dartmouth, he climbs the hill known as ‘Jawbones’, has an adventure involving the Corporation Abattoir and some escaped bullocks, and continues with a long tale about a film he had watched being made (and indeed had advised on!) at the village of Blackpool the previous summer, which again adds nothing to any actual knowledge of the area. And neither, once again, are we told the title of the film. One is entertained and aggravated at one and the same time!

So our walker continues to Slapton Ley, where the reader is treated to one of HW’s fine descriptive passages. Today the area is renowned for its role in the Second World War as a training ground for American soldiers for the D-Day Landings – codenamed ‘Utah’. It is also today a Nature Reserve of International importance (a RAMSAR site). In 1933 it was merely a good area for local fishing and a quiet holiday refuge for the very few.

HW continues to Torcross at the other end of the sands. Today the beach at Torcross contains a memorial to the 749 American soldiers killed during the D-Day rehearsal on 23 April 1944, when they were attacked for real by German E-boats. All kept was secret at the time for morale purposes. In 1933 the place was a very small and quiet seaside fishing hamlet.

In the bar of the local public house he is told about the ‘watchers’ for salmon on the cliffs, and so the next morning he sets off to find them. The reader is treated to some excellent descriptions of the art of salmon fishing: both of HW’s own experiences of river salmon, and of the sea fishing he watches here.

He now meets some children, three boys and a girl, who befriend him:

The girl called Ann, a tall and graceful creature who looked about 13, but who told me she was nearly 16, requested to be allowed to guide us to some quarries which were full of the most interesting things; and so we all went to the quarries.

So HW is led onwards and upwards (literally and metaphorically) to a succession of quarries. Later, after refreshment in the Cricket Inn at Beesands (the next village along the coast):

Ann and her brother and the Leeds boy were running back along the road half a mile away.

Thus the first fateful meeting with Ann Edmonds (called by HW ‘Barleybright’, ‘Bb’, or ‘ACE’ – after her so appropriate initials for the fine pilot that she became; she joined the Air Transport Auxiliary in the Second World War, ferrying much-needed Spitfires and Hurricanes to front-line RAF airfields), with whom HW fell instantly in love, which was to cause him anguish and unhappiness for several months.

His diary recorded:

Met lovely girl, Ann Edmonds . . . At night wrote to Ann Edmonds, but did not post it, to what use?

And the next day:

Lingered at Torcross and Beesands and saw salmon netting. . . .

[That night:] Melancholy, oh damned lonely and loveless and death-haunted.

But there is no hint of any of this in On Foot in Devon.

(For further details about Ann Edmonds see Anne Williamson, ‘Barleybright, or The Torcross Venus’, HWSJ 46, September 2010, pp. 56-70.)

There is another cryptic reference here to one Justice McCardie, the report of whose suicide HW reads in the paper. HW refers to him again in the last paragraph of the book where we learn that he had actually known this eccentric gentleman. In his highly emotionally charged state at that point HW no doubt felt great empathy for the other man’s plight. (See Following Henry Williamson’s Footsteps for more information.)

HW continues his ‘walking’ tour. He sees a ‘strong and striking figure of a woman in sea-boots . . . Miss Ella Trout . . .’. This is a nod to a lady decorated for her services in connection with rescue work at sea during the First World War.

Then he finds another cliff-watcher: an old man who, when he sees a salmon in the sea far below, holds out his hat and shouts to the fishermen on the shore, alerting them. The description here is reminiscent of the scene in Tarka the Otter, when the old man (his wife’s father, Charles Hibbert) raises his hat when he sees the otter, leading to its death.

Our walker now turns inland, avoiding the splendid (but no doubt difficult) cliff path – where ‘years ago’ a village had been more or less washed away in a storm. (That year was 1917, when HW, as a transport officer in the Machine Gun Company, was at the Front in France.) He eventually arrives by ferry at Salcombe. The next day on starting off for Kingsbridge it begins to rain, and so he catches the bus.

So the book and this tour ‘On Foot (!) in Devon’ ends with the author wondering if he will ever return, or:

see Ann . . . and the others, and the salmon which had travelled three thousand miles, to find only -- . . . and wondered if in a new age salmon would leap again in London river? One day, perhaps, tomorrow, and tomorrow, and tomorrow.

That last phrase is from Macbeth, Act 5, Sc. V: the speech on the death of Lady Macbeth, which begins: ‘Tomorrow and tomorrow and tomorrow creeps on this petty pace from day to day . . .’, and ends: ‘. . . it is a tale, told by an idiot, full of sound and fury, signifying nothing.’

Not an idiot; not just full of sound and fury; certainly not signifying nothing; but a tale, apparently artless and simple, which is actually full of riches for those who bother to look and unravel. One Foot in Devon is quite a mini-biography in fact, and a course in reading matter: certainly a picture of a time now long disappeared. It should be appreciated as such.

*************************

(The reviews for On Foot in Devon were pasted into a large scrap book by Ann Thomas.)

The Spectator (W. Beach Thomas), 23 June 1933:

A singularly gay, light-hearted and at the same time useful and accurate guide-book (written by a very good naturalist) . . . The author is soaked in North Devon: its old stags and Tarkas as well as its country people, and nearly all the incidents are admirable. [But] . . . he falls foul of an old and half-extinct book [that by the father of Edmund Gosse – first class on marine biology (seaweeds and seaside animals); a book which Beach Thomas greatly admires].

Bristol Evening Post (B.N.), 24 June 1933 (9-inch column):

Mr. Henry Williamson keeps strictly to the coastline of this delectable county . . . but these walking tours . . . are no ordinary ones. [Various examples are picked out.]

Observer, 9 July 1933:

Mr. Williamson is so pleasant a travelling companion that it does not much matter where we go with him. In this book he takes us for a walk down both coasts of Devon, but it might be anywhere – anywhere away from Beauty Spots, “a Beauty Spot being a place made horrible by humanity”. . . . The country, as we see it, is a reflex of Mr. Williamson’s whimsical enjoyment of it . . . [relates the story of the gipsy’s puzzlement over the word ‘bored’.]

Daily Express (James Agate), 6 July 1933:

Here is a charming book on walking in Devon, by one who has not only lived in the country but walked over it. Mr. Williamson has the proper kind of scorn for tourists [who merely gaze from car windows etc.].

Leeds Mercury, 7 July 1933:

A delightful book . . . Mr. Williamson does not tell us where to walk. He walks with us and enlivens the way with a boundless fund of joyous anecdotes. Guide books are tedious reading at the best . . . but Mr. Williamson, who has no literary nerves . . . [relates tales of litter: HW and orange-peel – Mais and banana skin]. I recommend a book as readable out of Devon as in it.

The Times, 13 July 1933:

Mr. Williamson’s book does not suffer from an excess of emotion, so determined is he to control himself before his audience. He parodies the guide-book style and pays the penalty of facetiousness. Yet, with all his superior feelings about guide books which contain “real facts” he has given what is demanded first of all from such books, that is guidance. He knows Devon from years of residence there and in describing two tours north and south he provides the salient points about the scenery and the things of local interest which visitors want to know. These would seem to be the affairs that least earn the regard of Mr. Williamson, but he kindly spreads them before his weaker brethren. Every man has his whim. The raven is Mr. Williamson’s . . . [it permeates the book – relates several raven items].

(This reviewer also takes exception to HW’s denigration of Gosse: ‘Does anyone read the books of this unnatural natural historian now?’ To which the answer is that scientists do.)

News Chronicle (Clennell Wilkinson), 11 July 1933:

There is a surprising variety in modern guide-books – largely because they are all so anxious not to appear like guide-books. . . . Mr. Williamson is as unconventional a guide book writer as any reader could desire. He adopts a tone of studied flippancy . . . [including] . . . playful reference to his own earlier works and to “a most nauseating anonymous novel attributed to myself”.

When it becomes necessary to introduce a few facts, he quite frankly lifts a large proportion from an old, out-of-print guide-book. . . . This method of attack is not nearly so irritating as it sounds; in fact you soon get used to it. You even find yourself looking forward to Mr. Williamson’s little jokes which, if seldom subtle . . . enliven the way. And every now and then he will pause and give us a perfectly serious passage, in his best manner, about the countryside that he loves. But I do not think that he really likes writing guide-books.

Western Morning News, 13 July 1933:

‘Notes of the Day’ [A Defence of Sidmouth!]

Sharp on Sidmouth

“Sidmouth”, says Mr. Henry Williamson in a new book, “is no place for the hiker. It belongs to its inhabitants, and in particular to the coterie of retired service men and others of the type who live in similar places all around the coast.” The author’s experience must have been unfortunate to generate such gall. . . .

Sidmouth admittedly carries itself with an air as, indeed, it is thoroughly entitled to, remembering its association with Royalty from days before the Battle of Hastings. . . . [attitudes depend on the person . . . some have a flamboyancy that jars!] Mr. Williamson’s off day at Sidmouth must be the exception that proves the rule.

[Which little homily rather reinforces HW’s point I feel (perhaps it was meant to!).]

Birmingham Daily Mail, 2 July 1933:

NORTH AND SOUTH

RAMBLES ALONG THE DEVON COAST

[Quotes passages from towards the end of the book, including lines quoted here in the main text about the view.]

The Devon Coast is a favourite resort of thousands of Birmingham folk and many holiday ramblers will enjoy reading the ‘guidance and gossip’ which Mr. Williamson provides so interestingly. . . . Mr. Williamson attunes his monologue to the spirit of the true rambler. He is sometimes discursive to the point of tedium, but he is a cheerful and helpful guide with a keen ironical sense of humour.

Devon & Exeter Gazette, 30 June 1933:

. . . will be welcomed by all lovers of the county, . . . for the author has captured all the charm and fascination of the countryside and has translated it into a series of alluring pen pictures . . . the main object of the author is to show how beautiful and interesting a hundred and one comparatively unimportant things can be to the traveller . . .

Mr. Williamson possesses a breezy and good-humoured style . . . the author is a man who loves the tang of the sea, the call of the birds, and all the joyous ways of Nature. In brief, he is a good companion, carrying us along in spirit from village to village, from hill to hill, and giving the zest of living to every yard of the journey. A good piece of work well done.

Aberdeen Press, 12 July 1933:

DEVONSHIRE LOG

In this little book Mr. Williamson is at home, wandering in one of the unspoilt English counties which he knows and appreciates best. . . . is not a guide-book in any sense, but the log of a wanderer, rambling through old-world places and speaking to old-fashioned people, observing the beauties of the scenery and noting quaint customs wherever he happens to meet them. It is a glorious way to travel and a splendid way to describe, and Mr. Williamson’s book of its kind is delightful and just right.

(No source or date), a 10 inch column headed:

WEST COUNTRY BOOKMAN

Messrs MacLehose made a capture in securing Mr. Henry Williamson to write about Devon in their ‘On Foot’ series. I doubt however, whether they knew what they were letting themselves in for! [There follows a series of examples of HW’s bon mots.]

Never was a less orthodox, or a more readable, guide-book . . . On the way he gossips and philosophizes, criticizes and applauds, just as if the reader were his hiking companion. . . .

Personally I like his inconsistency. He condemns Westward Ho! and Clovelly for their charabancs and Sidmouth and Budleigh Salterton for their exclusiveness! When one is expecting information about places, he gives one reflections about ravens, salmon, trout, buzzards, beer and mankind. But, knowing Mr. Williamson, who would expect – or wish – otherwise?

North Devon Journal, 6 July 1933:

This excellent analysis deserves full coverage (in 1933 ‘the editor’ was A. J. Manaton):

Two Devonshire Books

REVIEWED BY THE EDITOR

Henry Williamson in Merry Mood: Jan Stewer as Playwright

“REEL” ENJOYMENT

Published on June 19th by Alexander MacLehose and Co., 58 Bloomsbury-street, London, W.C.1, “On Foot in Devon”, by Henry Williamson, is surely the most entertaining “guide book” one would wish to put into one’s pocket. (With its rounded corners, uncomplicated maps inside the two covers, and magnificently readable type, the book can be put in and out of the pocket as often as you like, with the certainty of each such occasion marking a growth of the friendly feeling between reader and book.)

Nobody who is familiar with the books of the creator of “Tarka the Otter” and “The Pathway” will expect Mr. Williamson to be conventional even within the confines of a tourist guide-book. You can’t straight-jacket a man whose literary departures from the line of strict social sanity are always “such harmonious madness”.

So it comes about that the latest addition to the “On Foot” series establishes a new standard in holiday guidance literature. If you want to tramp through Devon with Henry Williamson you have to put up with Henry Williamson’s company! And “jolly good company” he is, too. You will soon find you are not hiking with a gazetteer nor plodding along ‘bus routes with pedant of platitudinarian. Your journey is a joysome jaunt with a philosopher who breaks all the rules of precise argument and who carries with him the heart of a mischievous schoolboy.

The spirit of the book is delightfully suggested in the sub-title added by the writer to the publishers’ prescribed phrase “On Foot in Devon”: Mr. Williamson gives the fortunate buyer of the book due warning when he superimposes the description – “or Guidance and Gossip. Being a Monologue in Two Reels”. After that, the reader must expect things! The dust-jacket of the volume tells me that

“Mr. Williamson in his book returns to the field in which he made his reputation – the description of country life and its scenes and sounds. He guides the reader in an observant and diversified walk down the Atlantic coast from Lynton to . . .” [and so on].

All this is true; but it does not tell me one half of the truth about this “return”. It does not, for instance, tell me that every page contains something that consigns to oblivion, as by a magic touch, the whole tribe of guide-books and travellers’ aids – some outrageous delight, some penetrating absurdity, some clear word of truth enwrapped in waggish nonsense. This self-appointed Dragoman gets as much fun out of the pilgrimage as his companions of the road. He asks no recompense but the compliment of accepting his tricks of make-belief as authentic tidings of his unseen convictions. If you will share his spirit – the very spirit of the open road – you shall learn to love his Devon and to know for yourself its kindnesses and the inspiration of its glory.

The book would be assured of many readers if only for its many allusions to living folk, whose names for no apparent reason except for the obvious privilege of being in Mr. Williamson’s surprising company. I can imagine a quaint army of relatives and friends purchasing (at 5s. a time) enough copies of “On Foot in Devon” to go right round the family circle. It is not quite so easy to imagine the proud Burgesses of Barnstaple buying the book for the privilege of reading all that Mr. Williamson says about “the oldest borough”- which is that it needs a new sewage system and has horrid iron spikes for the parapet of its Long-suffering Bridge. A little dab of healing balm healing balm is, however, applied when he says of Barnstaple “I like it much”. But even apart from thankfulness for small mercies, the citizens of Barum will want to be “in” on this new excursion because of the impartial partiality with which the author, after all, writes of our Devon. If he chides, it is for our blessing. If he wounds it is for healing.

Within the compass of a sketchy review like this, it is not possible to include much that is quoted. When I extract such ideas from the book as that “Appledore is 10,000 years old”; that at Clovelly “there is a parking place above this famous beauty spot for 10 million motor coaches, each with 90 wheels and 100 feet long”; that the “red beach pyjamas” of Miss Binnie Hale, the actress, are “still discussed” at Woolacombe since her visit last season; that the old inn at Challacombe has been enlarged “since ‘they days’” and is “now complete with the kind of grate to be found in any one of the 213,754½ new dwelling shapes built since the war” – well, you will have a glimpse into a storehouse of irresponsible humour that never seems to become empty.

From these evidences of the author’s light-heartedness it must not, however, be falsely imagined that “On Foot in Devon” is not a serious book of guidance. As a matter of delightful fact it contains just everything that you will want to know in addition to the many things you ought (and ought not) to know.

Of course, Mr. Williamson’s style is not free from the effects of foibles. If I may attempt an un-Bassed opinion, his writing of this book appears to have been influenced at many points (I had almost written “pints”) by what I will call the beer complex. Coming inns seem to thrill the author to a greater degree than the more important (in a book for itinerants) goings-out. I have somehow gained the impression that on his “tour” through Devon the guide and his imaginary party of sight-seers entered 927 pubs and consumed 9,000 pints of beer, ale or beer. I can only discover that they (between them) drank one cup of Devon-made tea. But I must read the book again (and again) to confirm or refute these rather wild statistics! For myself, however, who am not the only teetotaller who will be glad for Mr. Williamson’s fondness for “footing it”, I can forgive these and any other lapses from artistry in a Guide Book that devotes six whole pages on ravens, and in a writer who cannot conduct us through Exeter without reminding us, in a pen-portrait, of the Bishop “who in the present time was preaching and protesting against the institution of Birth Control clinics in Devon”!

[Sadly, what the editor wrote about Jan Stewer (another local writer) was not included in HW’s cutting: it would have been interesting to make a comparison!]

However, the pièce-de-resistance appeared in Punch. There is no original copy in HW’s archive: the item was typed out by Alexander MacLehose, and sent by him to HW.

Punch, 18 July 1933:

‘Day’s Marches in Devon’

Again the Messrs. MacLehose

Have on the market put

Another little guide for those

Who like to go afoot.

On Foot in Devon has been done

By Mr. Henry Williamson.

To North we go, to south likewise

On lovely coastal routes,

And Mr. Henry is our eyes

And we are in his boots,

And, if the weather sometimes rubs,

At least they call at lots of pubs:

Wild Nature also we may know –

Her simpler odds and ends;

And, if we’re lucky, as we go

The literary friends

Of Mr. Williamson will be

Outside their doors for us to see;

So, should you be about to hike

Along the Devon coasts,

Here’s just the little book you’ll like,

A book, you’ll find, that boasts

Fine photographs of timeless lands

All running out in yellow sands.

*************************

Designed by Charles F. Tunnicliffe, the scene, though not identified, is unmistakably Georgeham; though the duck pond is artistic licence! The cover of Anne Williamson's e-book Following Henry Williamson’s Footsteps is a modern photograph from the same viewpoint, making an interesting comparison.