THE DREAMER OF DEVON

An Essay on HenryWilliamson

Herbert Faulkner West

|

The Ulysses Press, London, 1932; limited edition, 250 copies.

Dedication: ‘For W. K. Stewart’

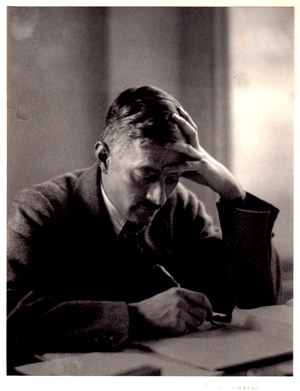

The frontispiece is a portrait of HW by Doris Ulmann:

Doris Ulmann (1882-1934) was an extremely well-known American photographer, who specialised in particular subjects: craft-makers such as Appalachian craftsmen; groups such as the Shakers and similar religious sects at work; and also writers. This photograph would have been taken while HW was in New York over the winter of 1930-31, but sadly there are no details whatsoever available. It is known that she invited writers to sit at her apartment on Park Avenue, when she would try to reveal their inner character. There are actually over a dozen poses of HW taken by her; they are of large size, mounted and signed. Here are four examples:

|

|

|

|

|

West’s monograph – about rather than by HW – arose directly out of The Gold Falcon, and would have added interesting detail about our author at that time – and indeed is still of interest to HW readers today.

HW met Professor Herbert Faulkner West (1898-1974) while on his first visit to America when he went to Dartmouth College in New Hampshire in January 1931 at the invitation of Professor W. K. Stewart (the dedicatee above, whom HW met on the boat out) to give a lecture. HW’s chosen title was ‘Hamlet and the Modern World’ (see entry for The Gold Falcon).

|

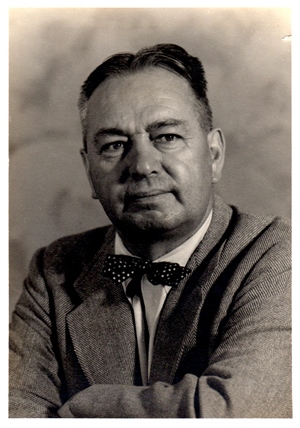

| Herb West in later life |

West, then Assistant Professor of Comparative Literature, was a bibliophile and, in due course, a writer of several books, of which this HW monograph was the first.

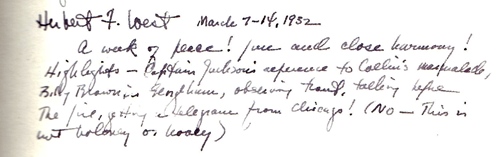

In 1932 West visited England as part of his research for a biography of Robert Cunninghame-Graham (1852-1936, a writer and adventure-traveller, politician and friend of W. H. Hudson), published as A Modern Conquistador in1932. While in England West visited HW at Shallowford and stayed for a week (7-14 March 1932), during which time he was given quite extraordinary access to HW’s manuscripts, past and current, and took notes preparatory to writing his essay. While there he also added his name to the Shallowford visitors' book:

The Dreamer of Devon is a 28-page essay, written throughout in discursive style – a wander through the thoughts of its author – opens with a lyrical passage on Devon:

This situation was exactly the sort of place that I expected to find Henry Williamson living in.

We learn there is a German helmet from the war hanging next to the fireplace over which hangs HW’s Nevinson etching (‘A Group of Soldiers’) and a woodcut by Kermode (from The Patriot’s Progress).

The ghost which haunted Hamlet was a weak thin wraith compared to the ghosts which haunt Sassoon, Blunden, Tomlinson, Williamson, Graves, and others.

This is, of course, a reference to HW’s ‘Hamlet’ lecture but without explanation: so it appears as if this is an original thought by West, and not quoted from HW himself. We learn further that in HW’s study there are many books about the war, including two by HW himself (The Wet Flanders Plain and The Patriot’s Progress). West comments that post-war neuroticism is due not just to the war itself but also to the post-war situation (surely taken from HW’s own thoughts), and mentions Willie Maddison (hero of HW’s early series of Flax of Dream novels), who is Williamson.

His mind, turned too long upon itself, enjoying in its own solitude, the inner landscape of the soul, the prey to imagined fears, dreaming of some Utopia . . . soaring to a belief in an impossible and unearthly love, had woven for itself a set of ideals which clashed inevitably with the compromises the world of experience forces upon all men. So he was unhappy and indulged in a great deal of self-pity.

A better description of HW’s own inner character could not be made. West goes on to highlight two keynotes of HW’s character: ‘Imagination and Individualism’. (That would surely have to be true of all great writers!)

West describes the scene at Dartmouth College:

This delightful college town; on the banks of the Connecticut River and at the foothills of the White Mountains, was in February a world of white’ [that being the time when HW was there in 1931].

|

| Photograph captioned on the back: 'HW Dartmouth College New Hampshire USA 1931' |

He notes that HW was not much of a skier and eventually turned an ankle, as in The Gold Falcon.

During his stay he gave a lecture at the college on the war and its effects on his generation. . . . I have never heard one so well written, or as sincere and moving . . . [and he has heard many great writers]. He introduced to the audience some war literature [including] the war poems of Wilfred Owen. I hope that this address, which he also gave at Harvard and Yale University, will sometime be printed.

[See also The Gold Falcon review section where a letter is quoted from a student who attended this lecture – and was very impressed.]

At Shallowford they listen to Tristan and Isolde and Rudy Vallée records, ‘whose crooning voice Williamson liked and had heard in a New York night club the year before’. (He has quite a major role as Jack Starlight in The Gold Falcon.)

West mentions the presence of Ann Thomas, knitting by the fire and HW’s wife Gipsy also (interesting that he should put them in that order, even at this early stage in the relationship) and describes HW’s study and the books it contained.

They look at The Star-born (not yet published at that time) which HW reads ‘with all the feeling he is capable of’.

Through his descriptions of the walking and talking between the two men there emerges a lively picture of HW at this time. We also learn he is ‘planning a book to be called ‘The Water Dreamer’ about a trout’. (This became Salar the Salmon, published in 1935 – although there is a made-up blank book with that title on its cover, so it was quite a serious thought.)

A stag hunt goes by, and we hear HW’s thoughts as related in his book The Wild Red Deer of Exmoor.

Proofs of The Labouring Life arrive, and West describes HW standing correcting them, comparing galleys with page proofs, while listening and beating time to Tristan and Isolde. (What a pity there is no photograph of this event!)

He does whatever he does well, and is a master for detail and exactness, whether he is dealing with writing, correcting proofs, keeping the hearth clean, or seeing that his automobile runs perfectly.

(Exactly so!)

Otters are a thing of the past: they are now a pest that kill and eat his precious trout. (It must be understood that HW put an enormous amount of time and energy into re-establishing trout in the River Bray that ran through the meadows at Shallowford; not so much for the actual fishing, but so that he could get all the details for the proposed salmon book as exact as he had done for Tarka the Otter.)

At night: ‘The moon and the evening star appeared in solitary loveliness over Castle Hill’: which reminds HW of earlier times and he quotes from his first book The Beautiful Years.

HW shows West ‘Tarka’ country: this leads into the interest that T. E. Lawrence (Lawrence of Arabia) took in the book which led to the friendship between those two men. HW acknowledges his debt to TEL’s influence, although they see nothing of each other: ‘It is like the stars, each in its orbit.’

Then, quite extraordinarily, HW also shows West his early writing in the large folio volume which contains in great detail his intimate thoughts and ideas of the early 1920s (which I call his ‘Richard Jefferies Journal’ as it pays full tribute to Jefferies). After looking at it briefly (it was too intimate for the rather mundane West), he feels that HW as a young man was lacking in healthy sexual experience which caused the self-pity evident in Maddison/HW (a rather glib statement); but that ‘the diary revealed tremendous idealism’. (That Journal is a most poignant expression of everything HW felt and thought in those years so soon after the War, when his every nerve was raw. It also contains much early writing that shows HW’s development as a writer.)

West goes on to state that the revised Dream of Fair Women, written while in New York in 1930, showed HW’s increased maturity.

A visit to Georgeham reveals how well HW had ‘caught and preserved the true and real village’ in his two ‘Village’ books. Then they go on up the hill to HW’s Writing Hut in his field at Ox’s Cross.

In the afternoon we sought the heights above Georgeham, where Maddison wandered and indulged his love for Nature. . . .

What Edward Thomas wrote of Richard Jefferies may, I think, be applied with equal fitness and truth to Jefferies’ disciple, Henry Williamson. . . . “He drew Nature and human life as he saw it, and he saw it with an unusual eye for detail and with unusual wealth of personality behind. . . . he turns from theme to theme, and his seriousness, his utter frankness, the obvious importance of the matter to himself, give us confidence in following him; . . . it is for his way of seeing, for his composition, his glowing colours, his ideas, for the passionate music wrought out of his life, that we go to him. He is on the side of health, of beauty, of strength, of truth, of improvement in life to be wrought by increasing honesty, subtlety, tenderness, courage and foresight. . . .” Readers of Williamson’s finest work, much of which is still to come, will find for themselves this heritage of Jefferies, visible in Williamson, which is theirs as readers of the best in English literature.

(A Dreamer of Devon was reprinted in its entirety in HWSJ 31, September 1995, pp. 62-70.)

*************************

On his return to London from this Devon visit West met Edward Garnett (probably to do with his biography of Cunninghame-Graham: both Garnett and his father had helped him and Hudson – and many others including HW – as is shown by a letter to HW dated 1 April 1932, which reveals that HW is fuming because West has revealed that Jonathan Cape, the publisher, has shown Garnett a copy of the ‘anonymous manuscript’ (that is, The Gold Falcon), and HW thinks that West was involved in this ‘treachery’. West is denying treachery and explaining what he thinks happened. But we know HW was paranoid about the secrecy to be maintained about this book, which was not yet published at this point. He was afraid that Garnett would reveal all and ruin the incredible edifice he had built up.

This incident may have driven a wedge between HW and West. Certainly, when West published Modern Book Collecting for the Impecunious Amateur in 1936, HW took great exception to the remarks therein about himself.

The section on HW begins, after a sentence of praise for the nature books:

As a writer of fiction I feel he has been too introspective . . . [concludes that he is not a novelist]. It is surely true that the publication of The Gold Falcon hurt his reputation as a writer. . . .

West continues in this vein for most of the titles – damning with faint praise – but The Village Book and The Labouring Life get full praise. Mainly it is almost just a catalogue of titles. There is a further section on war books in which again HW features:

Henry Williamson’s contribution to war literature consists of two books written by himself [i.e. The Wet Flanders Plain and The Patriot’s Progress], and two books he helped others to write [i.e. Douglas Bell, A Soldier’s Diary of the Great War, and Victor Yeates, Winged Victory].

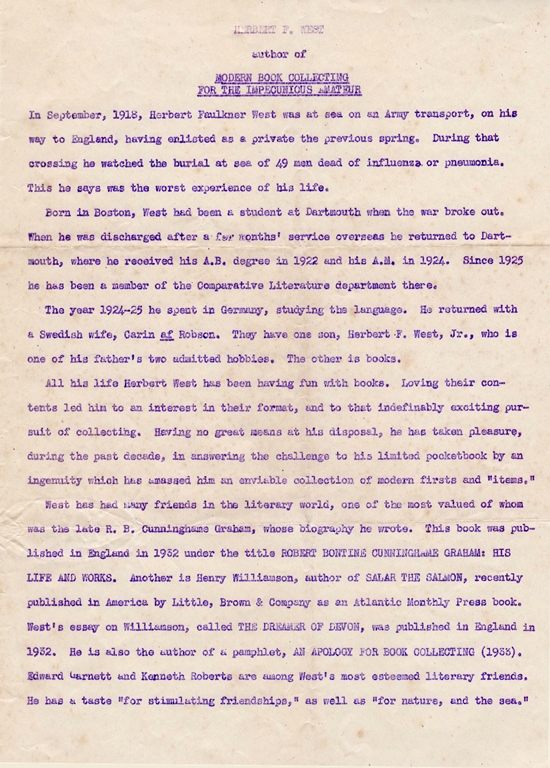

This time, extremely faint praise! HW was not amused. Little, Brown, the publisher, which by then had also published Salar the Salmon, had sent HW a blurb about Herb West, together with a letter that, innocuous enough in itself, only served to rile HW further:

HW immediately typed a heated 2-page response to the poor Miss Bolton, shown below; which, on more considered reflection, he decided not to post (for the top copy is in the Archive); but one wonders what his actual reply was!

*************************

There is then a long gap in the letters file from this point to the 1950s, when West made a few (possibly biennial) visits to this country regarding the book trade (he had become a bookseller), and they met up again on at least one of them – although HW did not make any great effort for further contacts.

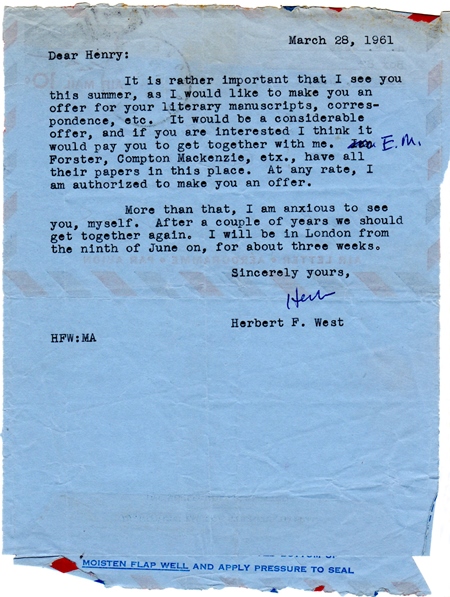

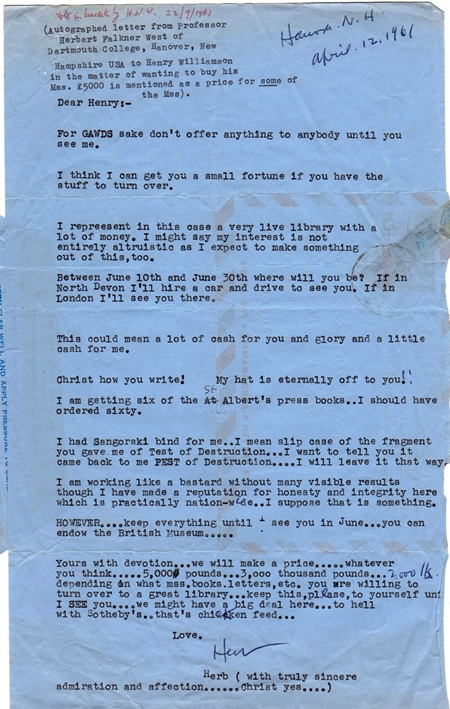

On a visit in 1961 West offered to buy HW’s manuscripts for the Dartmouth Library, for an amount that he claimed would make HW’s fortune.

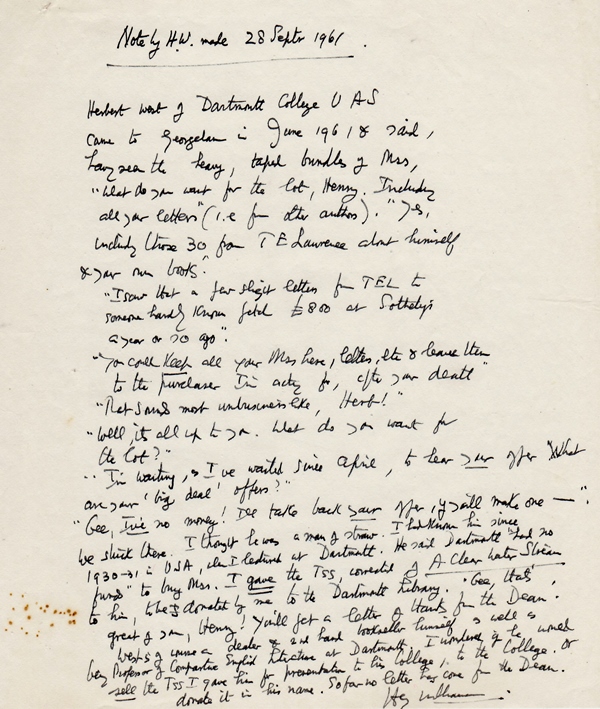

But this proposal did not get much further; indeed West seems to have retracted his first enthusiastic ideas. The end result was that HW gave West the manuscript of A Clear Water Stream (1958) to be handed over to Dartmouth. The following is HW’s version of events:

An official letter did arrive almost immediately after this outburst.

When Herbert Faulkner West died in November 1974 the Dartmouth Alumni Magazine wrote a glowing obituary: ‘a favourite teacher of thousands of Dartmouth students over his 40-year teaching career . . . a man of many talents. He was teacher, writer, critic, bookman, publisher and artist.’ HW is mentioned as among his many writer friends (as is Henry Beston, whom HW met at The Tomorrow Club in 1920 – West mentions Beston’s name in one or two letters to HW).

West’s letters to HW, written in an untidy hand, have no merit or style in themselves, but are of interest because he frequently mentions literary names.

*************************

Walker Burns relates further details about Herbert West, and points out that there is considerable material concerning these two men in the archive at Dartmouth College (see HWSJ 45, September 2009, pp. 51-4, part of Burns’s ‘Grove Street Blues: Places and People from Henry Williamson’s First Trip to North America 1930-1’).