THE WILD RED DEER OF EXMOOR

A Digression on the Logic and Ethics and Economics

of Stag-Hunting in England To-day

|

|

| First trade edition, Faber, 1931 |

Privately printed limited edition, 75 copies, issued in a pale green card slipcase, July 1931 (none of which were for sale)

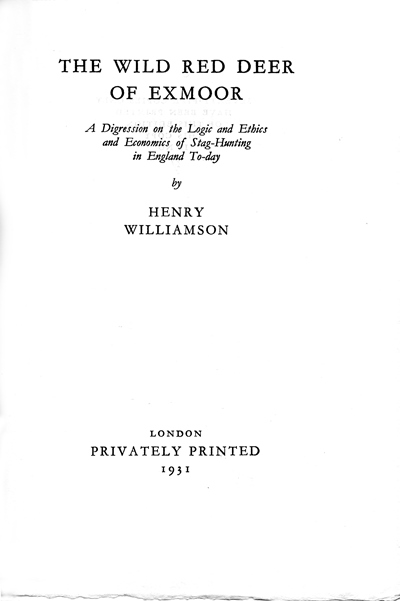

Ordinary (trade) edition: Faber & Faber, August 1931, 2/6d

Dedication:

TO

THE GENTLE READER

Title page:

The book is short: 58 pages (pp. 7-64) only of actual text, in a size just slightly smaller than our current A5, roughly about 13,000 words.

The somewhat ponderous sub-title is misleading, detracting, and distracting, since this work is an interesting, well-argued exposition giving a balanced, and at times amusing, account of two opposing points of view: those for and those against the hunting of deer. Particularly it shows us that the theme is not just a black and white opposition but has many nuances of opinion, and that those who argue most vociferously against are often hiding their own sins, whether consciously or subconsciously or even without conscience (so true in many walks of life).

***********************

There is very little in HW’s archive to throw any light on the background of this book. An enigmatic and teasingly intriguing appointment pocket diary entry for 16 April 1930 states:

Fortescue to lunch. . . . The Wild Red of England. [sic]

Lord Hugh Fortescue (4th Earl) (1854-1932) was HW’s new landlord, on whose estate at Castle Hill, Filleigh, he was renting the Shallowford cottage. Lord Fortescue was the older brother of Sir John Fortescue (1859-1933), who had written the ‘Introduction’ for Tarka the Otter. HW would have had to entertain the Earl on his own, as his wife had given birth the previous day to their third child (and first daughter) in a local nursing home, although this event is not mentioned in this diary. (Note: there is no diary proper extant for 1930.)

One deduces from that brief note that the two men discussed (as would be a natural topic of conversation between them) Sir John’s famous book The Story of a Red Deer,published in 1897 by Macmillan. This charming story has an ‘Epistle Dedicatory’ to ‘Mr. Hugh Fortescue’, beginning ‘Honoured Sir’. Nine years old at that time, Hugh (1888-1958) was the son of this present 4th Earl and became the 5th Earl on the death of his father in the autumn of 1932. Sir John’s book tells the life-story:

of one of our own red deer, which, as they be the most beautiful of all creatures to the eye, so be also the most worthy of study by the mind for their subtlety, their nobility and their wisdom.

The letter ends: ‘Your very loving kinsman and faithful friend to serve you, J.W.F., Castle Hill, this 26th of September, 1897’. The affection of the uncle for his nephew is heart-warmingly obvious.

The story tells the life-story of a red deer stag, its growing up and adventures on the moors, its courting of a hind, the various other creatures with which it comes into contact, ending with a hunt and the inevitable death of the stag – all very much as Tarka tells the life-story of an otter, but in a very different style. It is indeed a story written for young people and, charming and absorbing though it is, contains a great deal of Victorian whimsy.

This conversation over lunch (as I am presuming occurred) would have brought thoughts about deer to the forefront of HW’s mind, and may perhaps have given him the germ of an idea for a new book. But he had already written his own short story ‘Stumberleap’, printed in The Old Stag (1926), and a short essay ‘Hunting to Kill’, which had appeared previously in a magazine, of which more anon. However, he certainly did nothing about this until after his return from the USA in the spring of 1931.

The only indication of this book is in three letters from his friend and publisher, Richard de la Mare, on Faber & Faber headed notepaper, dated 30 April 1931.

My dear Henry,

We are delighted at your suggestion that you should do an essay on the Wild Red Deer of Exmoor. Our own opinion is that if you want a fairly expensive limited edition as well (say at 15/-) it would be very much better not to publish it in the Criterion Miscellany [The Criterion was Faber’s house journal, edited by T. S. Eliot and already mentioned in the entry for The Village Book] but to do it on its own in a more permanent format, and say at 2/6d. That would mean that the essay would have to be rather longer than a Miscellany essay, and I should suggest from 20 to 25 thousand words. We should like, if you agree, to keep the limited edition down to 400 copies at 15/-.

De la Mare goes on to offer an advance payment of £75, with 10% royalties on the 2/6d edition, rising to 15% after sales of 5000, plus a royalty of 20% on the limited edition. That was quite a generous offer!

He also mentions in this letter details about the revised edition of The Dream of Fair Women (which HW had written while in New York the previous autumn), which they hope to bring out in June 1931 – so could HW make a decision quickly on the colour of the binding.

A further letter from de la Mare, dated 5 May 1931, shows that HW has stated that he only intends to write a short essay (as his original plan):

I can see that it is to be only a fraction of the length that I suggested.

This means Faber cannot offer such good terms as previously suggested – (these new terms are set out in such a convoluted manner that I cannot quite rationalise them). It is also obvious that HW still wants this to appear in the Criterion Miscellany, which seems a little perverse as he has been offered an actual book edition, which must surely have been more lucrative. That HW is further querying publication details for The Dream of Fair Women is also apparent.

These continual complications about contractual details over, it seems, just about every book must have been a great irritation to the various publishers concerned.

A third letter dated 9 June 1931 states that the proofs ‘of your essay’ are ready and would HW please correct them as quickly as possible. The letter gives details of the final contractual arrangements: the cost of printing a special edition of 75 copies on hand-made paper will be £8 (2/- a copy). So HW’s ideas have changed yet again. Apparently, according to Waveney Girvan’s Bibliography (1931), this limited edition was for HW’s personal use and copies were never for sale. This typed business letter ends in holograph:

We were so happy that you were able to come on Friday, & we enjoyed having you both with us more than I can say, Yours, Dick.

It is very tantalising not to have more details although some may still come to light in the future. As with all HW’s books, the manuscripts and typescripts and any ancillary papers reside in the care of Exeter University.

Girvan's entry:

***********************

The opening paragraph of The Wild Red Deer of Exmoor tells us:

Britannia magazine was set up in 1928 by the proprietor of what was known as ‘The Great Eight’ – those glossy magazines which included The Tatler, Illustrated London News, Queen, Graphic etc. – who asked Gilbert Frankau to be editor. Frankau (1884-1952) had fought throughout the First World War, and was at Loos, Ypres, and on the Somme. He was known as a First World War poet but also wrote a large number of novels. There is one poem in particular that would have resonated with HW: ‘Gun-Teams’, which begins:

Their rugs are sodden, their heads are down, their

tails are turned to the storm.

[. . .]

The blown rain stings, there is never a star, the

tracks are rivers of slime:

(You must harness-up by guesswork with a

failing torch for light,

Instep-deep in unmade standings; for it’s active service time,

And our resting weeks are over, and we move

the guns tonight.

The Britannia venture was not a success, and was apparently very short lived. There is no evidence of direct contact between Frankau and HW: no doubt his agent dealt with this item.

‘Hunting to Kill’ reveals the opposition of the sportsman, who wants to continue his sport, and the humanitarian, who wants to stop it: the author understands both points of view – the dichotomy of opposites – and he states that ‘their intolerant attitudes [towards each other] are identical.’

HW sets out, quite briefly, what these attitudes are based on and why. He too had once enjoyed the idea of ‘sport’. But he moves on to state: ‘a newer post-War point of view’. He explains his (and most soldiers) unthinking attitudes ‘hating those I had never seen because everyone else did so; doing towards those I did not hate acts which were considered glorious and noble.’

Then, relating that in terms of a hunt, he wonders: ‘has not enough blood flowed on the face of the earth already?’ And so we have a further instance of HW’s constant juxtaposing the war with life in the natural world.

However we are shown that life is not that simple. The author does not like the idea of otters being killed, but now that he is interested in trout (living at Shallowford on the bank of the River Bray) he thinks it is justified as the otter kills fish just for ‘play’ and will leave none alive.

Chapter, or Section, II describes a meeting of ‘Protest’ held in the Town Hall at Lynton under the auspices of the League for the Prohibition of Cruel Sports. The various comments and opinions of those present are recorded with all their amusing digressions and bigoted ideas, which gradually moves to the idea of shooting to control rather than hunting on horseback with hounds. The question of foxes killing chickens, and thus the livelihood of their owners, is raised by one; then the damage done by deer to crops – but shooting deer would only result in wounded deer, although the Chairman now argues that this is minimal. A further point is made about the drastic effect on the livelihood of all those who are dependent on stag-hunting, to which the reply is that organised drag-hunts would provide such people with an equal income.

The chairman points out that the activity of these hunts in August and September keeps many (most!) tourists away as they so dislike the disturbance or the sport: refuted from the audience that the sport provides a huge amount of tourism in itself (rich hunting Americans are cited).

The author ends this section:

It is interesting to note that this was 1931: the arguments and comments set out here are identical to the furore that occurred in the media in recent years in the run-up to the law on the banning of hunting with dogs, which came into being in February 2005.

Part III is a short (2 pages, about 350 words), rather clever little homily, combining thoughts of war, religion and the pursuits and ideas of Lenin:

. . . The World War caused and intensified many emotions; a few of these emotions were transmuted into what is loosely called religious feeling. Many emotions, many religions. Most of the opposition to field sports, called blood sports, comes from religious feeling, which one of the great spirits of this or any other century (Lenin) said arose from contemplation of the idler, gentler part of oneself.

Such religious feeling is compared then with the behaviour of a holiday crowd turning on a one-armed huntsman standing on the beach waiting for a stag to be retrieved from the sea by the boat hired for the purpose. The unstated inference is that the huntsman had lost his arm in the World War in the service of his country and for the freedom of those that were now berating him (rather reminiscent of HW’s recent The Patriot’s Progress) – thus turning the thought back to the opening comment.

The fourth section gives some general background about deer and information about the complications of compensation for deer damage (not necessarily always honestly claimed), paid by the Hunt. Again hunting and its opponents are given an equal voice.

Part V opens by stating that Sir John Fortescue’s book should be read, and his own ‘Stumberleap’ story also. He then proceeds to give a list of critical comments made about his story by ‘an authority who has lived among deer more than seventy years’. But HW counteracts these moot points by guoting Richard Jefferies’ Red Deer as corroborative evidence, and further quotes a letter from the Earl of Dunraven printed in the Daily Mail in 1926 proving that a stag was known to have swum across the Bristol channel in the past (as does Stumberleap in HW’s tale).

The sixth and final part relates the recent experience of our author as guest at a meet of stag-hounds. First a list of memory thoughts about various unhappy occurrences is given. This list encapsulates many of those short stories that made up the earlier nature books – those stories which I have pointed out nearly all end in the sudden death of the creature concerned: those stories which I feel are allied to HW’s experiences in the war. That the war is mentioned several times in this present book reinforces this thesis: at the end of this list of wrongs HW writes:

The snail is a delicate little wanderer in the starry dewfall, a slow small vegetarian; I blinded and burned them with quicklime on my garden seedbeds, causing them to froth with green slime like the green froth in the lungs of men writhing in chlorine gas.

His love for his flowers and vegetable garden outweighs his feeling for the ‘tender night-wanderer with his house on his back’. There is a great moral thought in there: cast out the mote in your own eye before you criticise other people’s sins.

So HW goes on to describe his participation in this hunt which basically consisted of cantering about over the moor and gives him the opportunity for a lyrical passage:

Heather, whortleberry, furze, bog-plants, bog-grass, the clouds trailing the grey sky among the steady-cantering horsemen.

Eventually they return to the hotel in Exford for poached eggs (‘the exploited brood dream of some man-ruined bird’) – reinforcing the idea that we cannot afford to be critical or take sides on moral questions, for our own every action is suspect.

That evening our author goes to a dinner party (this was possibly at the home of the artist Alfred Munnings who lived nearby), where he meets a friend who is a vegetarian and had been a conscientious objector during the war: ‘a genuine benevolent and gentle soul’, who questions HW’s actions in taking part in that day’s Hunt.

HW’s answer is that the act of riding is good for the constitution, thus: ‘decreasing intolerance, which would tend to decrease the possibilities of another European war’. This is the credo that was so central to HW’s life and thinking.

The author notes to himself that his vegetarian friend is eating turkey with gusto (which he justifies by saying that he does it to prove that his principles are not the master of him!). HW notes that he also remembers this man has rat-traps set in his garden. Both men smile to themselves over the foibles of the other: a further hidden subtlety of the moral undertone.

HW’s final paragraph is worth quoting verbatim. It leaves us with a tolerant view of the activities which have occasioned this pamphlet – or ‘digression’.

**************************

The file is very sparse, only five items, but they are amazingly detailed.

Somerset County Gazette,19 September 1931; not signed, 26½ column inches:

THE WILD RED DEER OF EXMOOR

STAGHUNTING AND ITS ETHICS

FAMOUS AUTHOR’S VIEWS

MR. HENRY WILLIAMSON ON A

CURRENT PROBLEM

The ethics of staghunting, as conducted on the moors of West Somerset and North Devon, form a subject of endless and bitter controversy, but the average man or woman has had so far few reliable statements of the humanitarian and economic points at issue. . . . Mr. Henry Williamson . . . sets forth all these points in a peculiarly interesting and unusual way. . . .

Mr. Williamson’s authority to speak on the subject is, of course, of the highest . . . [empowers him with] . . . a sympathy that is finely balanced in this study of a contemporary problem.

[The reviewer then takes the reader through more or less every aspect of the book.]

Bridgewater Mercury, 23 September 1931: repeats the review above.

Horse and Hound (‘I.C.’), 16 October 1931:

THE STAGHUNTING CONTROVERSY

[The review opens with the usual details of this book and HW in general. It then sets a moral tone about there being two sides to every question, an attitude unfortunately held by very few but inferring that Mr. Williamson’s book does:]

It is brief, but it is powerful; strong in its fairness to both sides – although, human nature being what it is, that will be accounted by some to be a weakness.

[The reviewer again takes the reader through the main points of the book with the occasional personal comment. Ending again on a moral note:]

It still remains among our chief necessities that we should know ourselves and examine into the composition of our thoughts and actions. I should add that the price is half a crown.

The Western Mail (J.C. Griffith-Jones), 8 September 1931 (15 column inches):

HUNTING TO KILL

ARE BLOOD SPORTS ESSENTIAL?

MEN, GUNS AND THE RED DEER OF EXMOOR

Recently a prominent follower of the Devon and Somerset Stag Hunt was drowned during a hunt.

The tragedy was hailed with almost fiendish delight by a number of opponents of the sport all over the country. Remarkable letters were sent to the dead man’s relatives, rejoicing in the manifestation of God’s wrath against murderers of innocent animals, and expressing the hope that a similar fate would befall many more of the hunters!

Thus once again fierce controversy rages around the wild red deer of Exmoor. Is stag-hunting cruel? Is the sport compatible with ethics? The sportsman and the humanitarian, as ever, are at variance.

Mr. Henry Williamson, the distinguished novelist and nature writer, in . . . , dispassionately states the case for and against stag-hunting. He is peculiarly gifted for the task. [States the various raisons d’être and follows with a resumé of the book.]

Mr. Williamson reflects on all this, as you and I, average thinking people, reflect. [But it is marred for him] by an overwhelming feeling of anguish at the lost harmony of the world.

[The reviewer asks the question:] What is humanitarian? What is the dividing line between the humanitarian and the sportsman? [It is not really answerable. And – showing that he has grasped the inner message of the book – he ends:]

Nearly 300 red deer were killed last year. Yes, and a million men were killed in the war – shot down, blown to bits, suffocated by gas, hunted to a terrible oblivion.

There is, you may say, no link between these two things. Isn’t there? One day, perhaps, we shall learn to bridge the gulf between feeling and thinking.

Inverness Courier, 22 September 1931:

*************************

The spine and front of the limited edition:

The dust wrapper of the trade edition, this one somewhat stained and foxed with the years: