THE STAR-BORN

(A pendant to The Flax of Dream)

(The book supposedly written by Willie Maddison in The Pathway. As such HW’s name did not appear on the title page as the author – although it was on the spine and the dust wrapper!)

|

|

| First edition. Faber, 1933 |

Some first edition page proofs

First published by Faber & Faber, 1933; with wood-engravings by Charles Tunnicliffe

Limited edition of 70 copies, Faber & Faber. As the trade edition, but bound in full vellum stained a light green, and with a signed certificate leaf

Revised edition published by Faber & Faber, 1948; with drawings by Mildred Eldridge

The 1933 edition was re-issued in 1973 by Cedric Chivers (Portway Reprints series) 'at the request of The London & Home Counties Branch of the Library Association'

Originally written in 1922-4, the book was published in 1933 with virtually no revision of the original ms: but there was radical revision for the new edition in 1948.

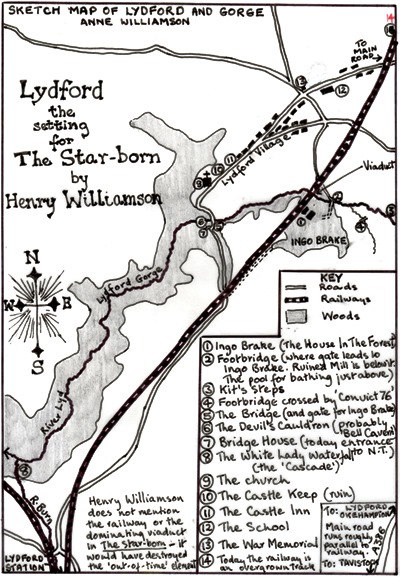

The story, a 'celestial fantasy', is set in the real world at Lydford in Devon, on the edge of Dartmoor, and its gorge and castle keep. As always with HW the descriptions of the scenery and natural world are superb, but there is the added dimension of another world – a Spirit world – inhabited by the Wind, Water and Air Spirits with ‘Quill’ the archetypal bird spirit. The Star-born is first a real baby, the son of Esther and brother of Mamis, who is spirited away one night by a barn owl (owls feature large in this book) to live with the owls in the ruin of the Castle Keep, to learn the wisdom of the universe and fulfil his real destiny. Then as an adult, totally unversed in any consciousness of the real world, he is returned (naked) to impart this wisdom to the humans of this world. Allowed to take one Spirit with him to help him in his task, he chooses the outcast, Wanhope. Arriving back at the place he had come from, he is taken in by Esther and the now grown-up Mamis, who is betrothed. They sort out his total ineptitude and unpreparedness for the world of humans and name him (Mr) Starr. But Esther has deep misgivings about his story.

Starr tries to put right the wrongs he finds around him, including chastising the schoolmaster for caning a boy, and taking all the boys out onto the moor. This reinforces the ‘education’ theme of The Pathway – indeed it is the underlying message of The Flax of Dream. There is a grand scene where Starr summons Mamis to the Gorge and gives what is virtually a ‘sermon on the mount’ on the evil of the world. But whatever he does to right wrong is misunderstood.

His message is unheard – he is powerless, and so is taken back to that world ‘Beyond’, in a most extraordinary scene which is more like the climax of a great operatic work in its effect. Accompanied by Wanhope he walks off through the snow into the moonlight, to find a joyous band of friends, Poets (of whom one can recognise Richard Jefferies, Van Gogh, Shelley, Byron, Beethoven). Wanhope becomes a stranger and is revealed at the last with a crown of thorns around his head:

And as the Star-born looked, he saw buds swelling out of the thorns, and from the buds broke white blossoms.

As he leaves, so Esther finally and tragically realises that he is indeed her lost son, and she wanders after him, calling his name. She is later found dead in the snow, ‘but on her dead face was a smile of deepest peace’.

*************************

|

|

Basically The Star-born is a book about good and evil, about what we are doing here on earth and why, contained within the more obvious context of the second coming of a Christ figure – the ‘Khristos’ factor – to earth. The whole book is mystical and visionary. Henry Williamson uses the concept of stars (an important theme in much of his work) and one born from the stars – from ‘Beyond’ – within which to present his ideas. Its content, or the meaning of its content, has an elusive, almost obtuse quality that perplexes and sometimes bewilders the reader. But that was indeed HW’s purpose: in some notes written on 20 December 1922, entitled ‘Phantasy’ (as he referred to the work at first), he stated: ‘The air of bewilderment, of eeriness, must be over everything. The whole action must be thrown as far away from the reader as possible’. (These notes can be found in facsimile in HWSJ 36, September 2000, pp. 56-7.)

Henry Williamson, through a local girl, Gwen Dennis, had met and become friends with the Radford family, who lived at Lydford. He was invited to stay with them early in 1922, and subsequently became a frequent visitor. Some of the elements of The Star-born and its characters are drawn from that friendship (for full background information on this, see Tony Evans, ‘The Radfords of Ingo Brake, Lydford’, HWSJ 36, September 2000, pp. 7-25). Mamis, however, is mainly drawn from his early love for Doline Rendle, whom he met in 1920, having had an intense affaire with her cousin Mabs Baker ('Eve Fairfax' in The Dream of Fair Women, the third volume of The Flax of Dream tetralogy). Unsurpisingly, Doline's mother did not intend her to marry a penniless author; she was destined for another – hence in the book Mamis marries Robert! Clearly the extraordinary scenery and atmosphere of Lydford and its gorge had a great effect on HW, and allowed his imagination to conjure up the surreal scenes which he then wrote into The Star-born. It is very possible that the writing of this book exorcised the troubles of his mind and psyche arising from his war experience, although of course it may be that he was recovering anyway by then.

|

| HW's early love, Doline Rendle, aged 20 |

The Star-born is a strange – I think one might say truly ‘extra-ordinary’ – story which moves backwards and forwards between the down-to-earth real world of Lydford village and the famous gorge of the River Lyd, on the western edge of Dartmoor, and a surreal world of spirits of nature who inhabit a further dimension unsensed by most human beings, but here shown as real identities, playing their part in the unfolding mystery (‘mystery’ as in the old sense of ‘mystery play’).

The history of the book itself is almost equally strange. When it first appeared in 1933, Henry Williamson tried very hard to maintain the idea that it was a book really written by Willie Maddison (the fictional hero of the four books of The Flax of Dream) and that he himself was merely the guardian and presenter of this book – Willie’s literary executor as it were. Thus his name did not appear on the title page as the author! Instead, he wrote an involved introduction to explain the complicated circumstance of this made-up background, which can only have served to add further confusion for his readers at the time. Although he removed this introduction from the radically revised edition of 1948, he still tried to maintain the illusion that the book was written by Willie Maddison.

This first edition was illustrated with woodcuts by Charles F. Tunnicliffe, who in May 1932 had written to the publishers of Tarka the Otter suggesting himself as a possible illustrator for a new edition of the book. HW had invited Tunnicliffe to visit and to work directly from the actual sites described. 'Tunny' (as HW came to call him) was soon hard at work and the resultant new edition was published to great acclaim. There quickly followed companion editions of The Lone Swallows, The Old Stag, and The Peregrine's Saga. (Interestingly, Tunnicliffe had little knowledge of birds of prey at this time, and HW suggested he visited a falconer to see falcons at close hand. A letter written by Tunny after this visit was headed with a superb drawing of the head of 'Sonia of Solva', and expresses his overwhelming emotions at the beauty of this peregrine.)

Tunnicliffe was asked to illustrate The Star-born, though he was unsure that he could capture the 'celestial fantasy' nature of the work. However, on 10 December 1932 Tunny arrived by train at Shallowford and two days later HW drove him across to Lydford in his open Alvis Silver Eagle sports car, where they stayed with the Radford family for a few days so that he could get details of the location exactly correct. His later letters reveal that he was very worried about his ability to capture the ‘other-worldliness’ of the Spirits, such a subject being totally foreign to his down-to-earth nature, but he rose superbly to the task. Tunnicliffe was a prodigious worker and on 28 December HW received a letter enclosing a set of draft illustrations in pencil and ink for the book. There is no doubt that the wood-engravings he finally created complement and enhance the text in an exceptional manner. The book itself was superbly produced, and used a heavy cream paper that enabled the engravings to be reproduced to a high standard. Most reviewers commented on his skill, though several had reservations about the ‘spirit’ ones. The subject perhaps made them uncomfortable.

As seen in The Pathway (the last volume of The Flax of Dream), Willie is writing this book and throughout there are several short passages from it, as that story builds to its climax, when Willie is tragically drowned in the estuary of the ‘Two Rivers’ (the Rivers Taw and Torridge in North Devon), and apparently burns his manuscript in a vain attempt to attract attention and help when he finds himself marooned on a sandbank out in the middle with a fast rising turbulent tide surge. That evening Willie had read the whole of his manuscript to three people: his cousin Phillip, a somewhat wild young man called Julian Warbeck, and the local vicar, Mr Garside (each representing a different aspect of humanity): all of whom found it remarkable and wonderful. Phillip and Julian are supposed to have reconstructed the manuscript from charred pages rescued from the tide’s edge the following day by Mary Ogilvie, the simple beautiful country girl who had loved Willie since childhood, and from their own memory of that final reading, and from Willie’s original notebooks found later, which contained many of his ideas for the book. Although it has a validity within the fictional scenario created by its author, it surely cannot have been literally believed by anyone.

*************************

The true history of the book has its own poignancy. For the real birth of this book goes back to Henry Williamson’s earliest days of writing – a time when he was in a state of nervous exhaustion and tension, trying to make sense of the world in which he found himself, and to make sense of his own thoughts and feelings about that world. His experiences of the war marked him for life, particularly the 1914 Christmas Truce, when he discovered that German soldiers also thought they were fighting for God and their country, and ‘Right’. Henry never forgot his dead comrades. Although The Flax of Dream does not directly deal with the war itself (his nerves were still far too raw for him to cope with that), much of what he felt at that time can be seen in the character of Willie Maddison in the last two volumes, those dealing with the post-war period.

When Henry Williamson was demobilised in the autumn of 1919 he had already begun to write seriously. At the beginning of 1920 he started to keep a Journal in a large folio book in which he recorded his most intimate thoughts. This journal is dedicated to the memory of Richard Jefferies, whose mystical work The Story of My Heart had been the catalyst that catapulted Henry through the barrier of his own diffident psyche when he had read it in early 1919, while on army duties in Folkestone. Feeling that Jefferies thought as he did was a revelation, and he determined to follow in his footsteps.

This journal reveals the turmoil that Henry Williamson was in at that time. Still in a state of nervous exhaustion and breakdown from the prolonged effects of the war on his highly-strung personality, and in the throes of metamorphosis as he struggled to become a writer, this vulnerable young man was trying to make sense of the world, and to sort out his thoughts and feelings about Christianity, and the role of Christ and God. It is these thoughts, raw and troubled, that are the genesis for what was to become The Star-born.

Apart from Richard Jefferies’ writing, Henry Williamson was greatly influenced by his Aunt Mary Leopoldina, his father’s sister. This interesting and educated young lady had a strong personality and was also highly imaginative. She had written two books published around 1910, neither more than short-story length, but of extraordinary visionary quality, both set in Greece where she had spent some time at the turn of the last century. As previously stated, one of these stories is the direct source for Henry Williamson’s overall title The Flax of Dream, and for several other elements within the tetralogy itself: the other, Voices of the Visions of the Night, is about a solitary and unhappy man in an idyllic landscape keeping vigil over the sleeping world. He is visited by a star, which in fact is seven (a mystical number) spirits (angels) descending from heaven to give him solace and bless him, to give him understanding and hope. All the elements from this story can be found in The Star-born.

Another potent influence on HW at this time was the metaphysical poet Francis Thompson, a volume of whose visionary poems was given to him by his aunt Mary Leopoldina in the early part of the war. The importance of the poet to HW is highlighted by the inscription he inserted into his own copy of The Star-born (shown below), and which exactly illustrates the theme and spirit of this book. Thompson’s metaphysical thought ‘my spirit’s deepening gorge’ is epitomised by Lydford Gorge, a physical split in the landscape. That God’s spirit can be found in all nature was the clarion call of the Romantic movement: hence HW’s Water, Air, Quill, and other spirits – all can be seen as aspects of God’s spirit, and as such they make a parallel to Christian thought.

When in early 1922 HW made friends with the Radford family, Lydford and its spectacular gorge was then still in private ownership (today it belongs to the National Trust). It was a wild and Romantic area, almost gothic in its atmosphere (and really still is). It is not difficult to imagine beings from an unseen world living there. HW was inspired to conjoin all those turbulent milling thoughts about genesis and eternity, the meaning of life and the role of Christ, into a story set in this very earthly, yet equally unearthly, landscape. Around this time he wrote a short and fairly simple two-page synopsis of his ideas for the story:

Gradually over the next year, this original idea was developed until the full manuscript of 160 pages was produced between February and April 1924. By then the first two volumes of The Flax of Dream had been published and the third, The Dream of Fair Women, was finished and at the printers. (It was published in June 1924.) In that volume Willie Maddison is seen to be writing ‘The Policy of Reconstruction, or, True Resurrection’.

As will have become obvious, HW, as is Willie in The Pathway, was at this point in his life distinctly of ‘the Left’, adhering to a socialism bordering upon communism. Some of this tendency was due to his reading and following of Richard Jefferies, who was particularly vehement on behalf of agricultural labourers (who led a very grim life in the second half of the nineteenth century). But it was also a fairly common reaction among those who had been in the war. HW, along with many others, believed that one of the prime causes of war was capitalism and the politics that went with it. Thus to take the opposite stance and think in terms of the good of the masses must be the correct path. In particular he was influenced by the work of the French writer Henri Barbusse, whose war book Le Feu had been a sensation when it appeared in 1917, and was greatly admired by HW. Barbusse was also an extreme left-wing socialist leaning towards communism. (Bernard Shaw was a prominent writer who also held such views – HW had met him at The Tomorrow Club in 1920.) That HW thought in this way can be seen in the thoughts of Willie Maddison, who constantly quotes the philosophy and writings of Lenin in the two post-war volumes of The Flax of Dream, much to the irritation of those who neither like nor understand him!

But during the period – covering several years – that HW was writing The Flax of Dream, he had matured as a person and as a writer. For various reasons he was moving away from the heavy ideology of Lenin: ‘The Policy of Reconstruction’ was no longer of vital importance to him. If he had so wanted he could easily have devised a way for Willie to retrieve the ‘lost manuscript’ from Folkestone – but he chose not to: ‘Policy’ was dead. Instead, as the final volume opens, Willie is seen to be writing a new version of his book on the redemption of the world, an allegory called The Star-born. But there was to be quite a long gap between the publication of The Pathway in 1928 and that of The Star-born itself in 1933. That must have made it all the more confusing for his readers at that time!

When The Star-born did finally appear, the text, most unusually for HW, for whom rewriting was a compulsion, followed almost exactly that full manuscript version written in April 1924, without revision. (This does rather beg the question whether Star-born was always intended to be the book involved: ‘Policy’ was always so very thin in concept as to be almost non-existent.) However, because of this lack of revision, the book contained juvenile phrases which really were not worthy of his present status (and which certainly irritated some critics). This was particularly odd as he had by then revised the three early Flax of Dream volumes because of this problem. This was not resolved until he made a radical revision for a new edition published by Faber in 1948, illustrated so beautifully by Mildred Eldridge, who really caught the spirit of the book in her drawings.

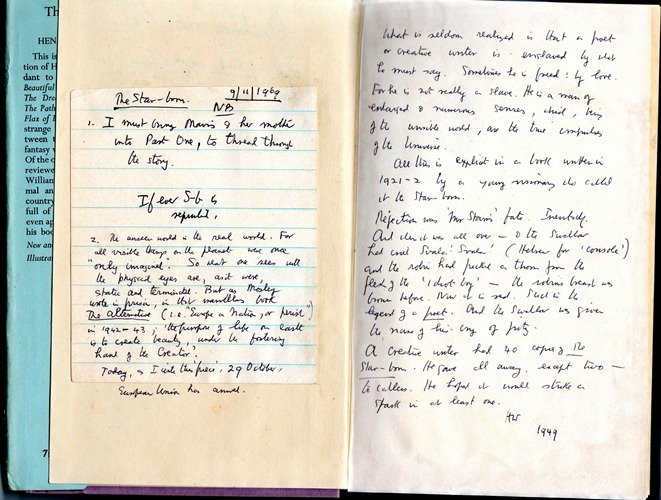

The fact that a new edition of this book came out after the end of the Second World War was not an accident. HW thought its message as relevant at that time as it had been to the First World War. In 1969 he thought it equally relevant to the new world-wide movement for conservation of nature and (with myself as assistant) planned a further major edition. But this did not come to fruition. It occurs to me now that perhaps he actually wanted a new edition at that time to enhance the message of his last great work, The Gale of the World, the final volume of A Chronicle of Ancient Sunlight, published in 1969. There are certainly many comparisons that can be drawn between The Gale of the World and a combination of The Pathway and The Star-born.

At the end of 1969 HW wrote a note which is pasted into the front of the 1948 edition that we were working from, which includes the following:

The unseen world is the real world. For all visible things on the planet were once “only imagined”. So what one sees with the physical eyes are, as it were, static and terminated. But as Mosley wrote in prison, in that marvellous book The Alternative (i.e. “Europe a Nation, or perish”) in 1942-43, ‘the purpose of life on earth is to create beauty, under the fostering hand of the Creator’.

Today, as I write this piece, 29 October, European Union has arrived.

One of the great strengths of The Star-born is the description of the scenery of Lydford Gorge and the village with its ruined castle keep (still there to this day), with all the detail of the natural life found therein: ferns and flowers, blossom and birds, stars and streams, creatures and cascades, animals and arbours.

But there is also a surreal dimension – an ‘above and beyond’ quality, which lifts the book far above an ordinary tale of natural history. In an explanatory note written in 1932, HW included the following points for an overview of the book:

Time: not stated, all clock-time, days, weeks, months, etc, ignored.

Story is meant to be on the verge of 4thdimension as it were; cf simplicity of Einstein . . .

Place: not stated, but locally is drawn roughly from Lydford Gorge & ruinous Castle Keep on western edge of Dartmoor.

Theme: the mind of a poet (natural man who is himself, unaffected by social strata, unaffected by ‘education’) . . . who grows and finds strength with the ‘spirits’ – a marvellous or ‘ideal’ childhood.

The book certainly has an elusive quality that perplexes and teases the senses. One is never quite sure whether one is in the real world or whether one has stepped through some invisible barrier into a further dimension, where the primeval spirits of an ancient lost civilisation abide. It is very subtle, like a gentle mist obscuring the real world where shapes of unseen others are dimly seen and heard: shadows that move just outside the actual line of sight. In fact The Star-born is an enigma. The book could be seen as a dream, and thus fits into the ‘dream-narrative’ writing idea I have examined elsewhere. (AW, ‘Save his own soul he hath no star’, HWSJ 39, September 2003, pp. 30ff.) Note that Francis Thompson’s poem encompasses ‘my dream’, and HW refers to Thompson’s death as ‘dream-tryst’.

The concept of good and evil has occupied the mind of philosophers since the time of Plato, who deemed it the ‘polarised opposites’ theory. This was taken up by the early ‘romaunce’ writers, and then Chaucer, Shakespeare, and epitomised by the Romantic writers, who greatly influenced HW (particularly Shelley and Blake, whose influence absolutely pervades The Star-born). HW was well versed in all these concepts, as I have shown in various articles in the HWS Journal (see in particular HWSJ 36, September 2000, ‘A Daffodyl in the Grasses of Mankind’).

It is probably true to say that HW did not entirely pull off what he set out to create, that in his efforts to obscure, or hide, his true meaning, he possibly lost his way in his own nebulous clouds, for The Star-born does contain many superficial flaws. However, that does not detract from the sincerity and truth of his prose, the force and delicacy of his descriptions, his power to delight and enchant us with this metaphorical and metaphysical tale: a story at one and the same time simple and complicated, entertaining and thought-provoking: an allegory that has much to offer modern society. But the book is open to gross misinterpretation, while HW’s own explanations, as always, only add to confusion of thought.

Read in the true spirit that it was written, you will find it breathtaking in its scope: for The Star-born is a window that allows us to see HW’s vision for a perfect world. A world he yearned for but knew neither would, nor could, ever actually exist. That neither Willie Maddison nor the Star-born succeed in their chosen (allotted) tasks is not an accident: HW knew that Utopia cannot exist in the harsh realities of this world, unless there are great changes – a re-birth – in the mind of mankind: all mankind. One could say: ‘When will they ever learn?’

Although the book is at once a message of hope and one of warning, it does not have to be read on that level. As with all good fairy tales, it is also a charming whimsical tale which tells the story of a lonely imaginative boy lost in his own world of make-believe. Make of it what you will: for Willie Maddison – and thus for HW himself – it was the ‘Truth’.

HWSJ 36, September 2000 was almost totally devoted to The Star-born; for example an excellent synopsis of the story-line can be found in Brian Sanders, ‘The Light of Khristos’ (pp. 5-6) and AW, ‘A Daffodyl in the Grasses of Mankind’ (pp. 28-49).

*************************

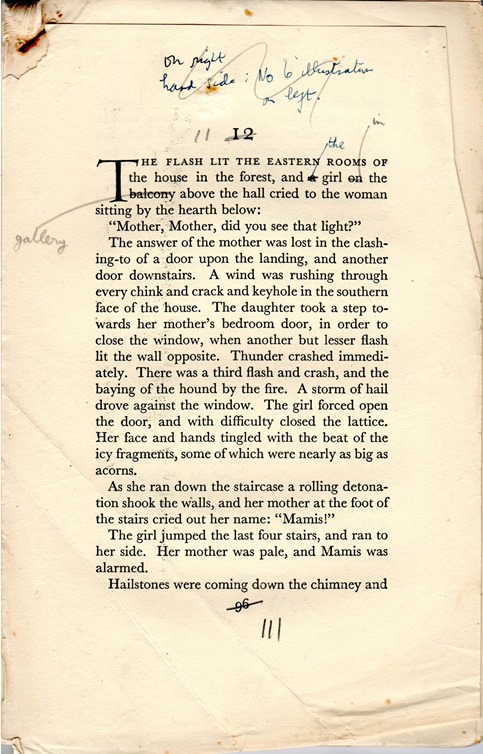

Some first edition page proofs:

The title and contents page, with early pulls of Tunnicliffe's woodcuts on very thin india paper pasted in – in the published book these lovely vignettes have changed places:

Chapter 11 sees the first appearance of Mamis, daughter of Esther and sister to the Star-born. The inspiration for the character of Mamis was Doline Rendle, an early love of HW's. Tunnicliffe made a woodcut portrait of Mamis, originally intended to be placed opposite to the first page of this chapter. In the event it was never used . . . though Mamis is remarkably similar to the studio photograph of Doline.

At the end of the book the Star-born is met by spirits, a band of friends:

Interestingly the manuscript corrections were not for the first edition but for the 1948 revised edition. The friends are not named, but HW certainly intended them to be identifiable. Tunnlicliffe's excellent woodcut aids recognition:

HW later wrote this explanatory note:

*************************

What did the critics make of this strange allegoric tale in 1933? Remember that it came after the huge success of Tarka the Otter and The Pathway – and that two war books had also been published. I stated in my 1995 biography (p. 153) that no review cuttings for The Star-born existed, but I have since found them (in 2000) at the home of HW’s first wife after she died, still in their Durrant’s Press Cuttings envelope. Most grasped some of its content but also were puzzled by it – understandably.

The Observer (Basil de Selincourt), 14 May 1933 (a long review of 35 column inches):

. . . This star-born book of his is well worth reading for the wealth and fineness of its contact with beauty and nature; and also because it finds Mr. Williamson and leaves him in the meshes of a great dilemma, the great dilemma – the old dilemma of the struggle for life. He tells the tale, the fairy tale – celestial fantasy he calls it – of a new redemption. We certainly need one; no man of sober feeling can fail to appreciate the motive which has led Mr. Williamson to write as he has. Nevertheless, although I have been touched by his book deeply, I must admit I have also been exasperated by it. . . . [de Selincourt enjoyed the nature, was somewhat bored by the various spirits, and exasperated by ‘Weary Wee’ and the baby talk, and was worried by the association with ‘that great friend of mine’ the barn owl.]

. . . The main purpose of Mr. Williamson’s allegory – I suppose an allegory must have a purpose – is to find in the reader’s heart that tender point at which he feels kinship with everything that lives.

[It becomes rather obvious, as de Selincourt wanders around the problem of killing to survive, which all nature does, that he has rather got off the point of the book itself, and never gets back onto it.]

Evening Standard (Howard Spring), 18 May 1933, headed, ‘Mr. Williamson mingles the spirit of St Francis with the manner of Winnie the Pooh’:

“The Star-born” is the outcome of profound feeling about a thing which has baffled the understanding of many men: the presence of pain in the world. . . . But having stated the problem, Mr. Williamson has no contribution to make to its solution or understanding. He has felt and not thought [but states that no-one has ever solved this problem]. But I do complain of the queer jumble of the beautiful and the banal which go to make this book. . . . I could not take kindly to the sentiments of St. Francis of Assisi annotated with extracts from “Winnie the Pooh”. . . .

Having imbibed from a spirit called Wanhope . . . the Star-born is hurled somewhat heartlessly back into mortality, to sink or swim. He appears in a Devonshire village, innocent as the angel . . .

[unfortunately the end of this review is too tattered to read – other than ‘A strange book ---']

John O’London’s Weekly, 27 May, 1933: the end is missing, so the writer unknown – but possibly/probably by Sir John Squire himself. The review reveals straight away that the real writer of The Star-born was not Willie Maddison, but Henry Williamson (but surely only the most naive would have thought otherwise!):

Mr. Williamson has contemplated his shadow for so long that he begins to believe it is someone else’s shadow. . . . Here is the same conflict between greatness and weakness as is present in all of Mr. Williamson’s works; the personal emotions overwrought and out of focus, the descriptive writing as the best of his master Richard Jefferies. Observation of everything [in nature] with a genius of the senses . . . but an inability to see within, to distinguish between the rhetoric of a mood and a sigh of Truth. . . . The complete lack of humour is hard to believe. . . . As for the Star-born himself . . . he has failed to make him anything more than a nuisance. A Messiah of this sort might very well be a nuisance to the conventional, but he would surely have more power than this ineffectual person. . . .

It is strange that all Mr. Williamson’s books have the same failure, the same ineffectual figure at the heart of them. Maddison in “The Pathway” is the only unconvincing person in the book. He is, in fact, not a person, but an embodiment of an incomplete ideal. In this fantasy he appears again, a half-realized theory among living people. He fails at last in his mission; but there is no irony in that, for he was created to be a failure. . . .

Mr. Williamson has not found himself yet . . . but that he will succeed seems certain.

Sunday Referee (Edward Crickmay),14 May 1933:

The work is supposed to have been written by Maddison who . . . believed it would be a revelation of truth. This latter large general proposition may not be examined here; but that The Star-born contains a full measure of that artistic truth which is also beauty cannot be questioned. It is a superb allegory of spiritual life developed through a multitude of earthly symbols. The texture of the book is that of a dream . . . [one cannot analyse it without damage but . . .] Mr. Williamson has found a really lyric voice . . . here, freed from the necessity of social realism, he rises to magnificent imaginative heights.

The Sunday Times (H. C. Minchin), 14 May 1933:

One closes this book with mingled feelings of admiration and perplexity. The author has a fine perception of beauty, as well in language as in scenery. Mr. Williamson – for the authorship, despite some preliminary mystification, is, of course, his – is known as a sensitive and observant naturalist, and these pages are permeated by the ripe knowledge of what, as an observer, he has felt and seen. But there is a jarring incongruity between this admirable exactitude and other features of the narrative which are chimerical rather than legitimately fantastic.

We do not experience such jolts and jars in reading "The Ancient Mariner", with which in its strong humanitarian feeling this story is comparable. We can accept Mowgli as a denizen of the jungle and a familiar of the beasts; we can see the she-wolf carrying him off; but to read of a little boy being spirited up the chimney by an owl, and being brought up by it in an "ivy-mantled tower", is a severe strain on the most willing suspension of incredulity. "Sonny" grows up in companionship of the spirits of the air, land, and water, and of a mysterious being called "Wanhope", who seems to be closely akin to Mr. Hardy's "Pities", but is eventually seen as crowned with thorns.

However, when Sonny is restored to earth and to a mother and sister who are strangely attracted, but do not recognise him – nor he them – the story begins to grip us. There is charming subtlety in the interactions of this very lovable trio. Poor Sonny is constantly coming into collision with the harsher realities of this our life, and the women are constantly hurting themselves in trying to protect him. Just as they are on the verge of recognition, the "star-born" vanishes; and his mother, who has sought to restrain him, is found lying dead in the snow.

Her death seems purposeless enough; and Mr. Williamson might reply, such is often the case. But on this occasion it appears unusually so. There is a hint, however, that Sonny's disappearance is due to grief at the loss of his sister, who had married six-foot-two of sporting Devon manhood, which drove him to a last plunge in a beloved stream. But all is left vague and indeterminate.

What a beautiful book, one feels, Mr. Williamson might write, if he would realise that it is a true instinct which bids us recoil in just dislike from that which is chaotic, and, while not shackling his imagination, would refrain from overstepping the bounds of fantasy.

The Times Literary Supplement (unsigned), 11 May 1933:

. . . The story is allegorical: and the allegory, it is clear, has a very real meaning for the author. But the reader is faced with many interpretations . . . he may probably conclude that, for anyone except the author, the pieces will not fit – the key to the puzzle is incomplete.

The Star-born, part figment of Esther’s dreams and part her still-born child [misinterpretation] . . . brought up among the spirits . . . until he was old enough to return . . . with a mission to mankind – not until he was fit enough to do so, for he was ever that, nor was the hopelessness of his mission ever in doubt. . . . the Messiah who does not understand his own message.

The Times (unsigned), 16 May 1933:

. . . The Star-born is a human child who has died at birth [not quite correct] and was brought up in a world peopled by owls and the abstract spirits of fish, flesh and fowl. After a period in which he learns, as it were from the inside, all the workings of Nature, he returns to the world of men to be rejected of men. Mr. Williamson does not elucidate his allegory: but he stimulates thought and wonder by the expression of a difficult creed – the creed of Maddison who wrote “in the period of despair which beset the youth of Europe immediately surviving the Great War.”

Morning Post (E.B.O.), 16 May 1933:

[After a lucid resumé of the plot peppered with a few comments this review ends] . . . But man must collaborate with ever-increasing kindness – that is the “moral” of a book which lifts us out of life’s littlenesses for a few immortal moments again and again.

The Daily Mail (T.C.M.O.), 18 May 1933:

When you are tired of the dust and the dirt of the mechanical age into which we have allowed ourselves to be driven, find a signpost to new life in the books of Henry Williamson. . . . who has sent out as memorable a tetralogy – “The Flax of Dream” – as has been presented by any author of today.

Williamson’s books are the greatest indictment of modern war that the soldier-writer generation has produced. And yet the war hardly comes into them. Now . . . is the book that everyone who knows Mr. Williamson’s work will have expected and hoped for. . . . And the thoughts and their expression could have come from no-one else in this generation.

But this is not a book for every reader! Unless you have known the fire that quickens the conscience towards your fellow man you may not find Mr. Williamson’s points to your taste. . . .

Western Morning News, 11 May, 1933 – headed: ‘DEVON TRAGEDY RECALLED’

[After a long introductory passage and several quotes throughout] . . . The story certainly is wistful and unusual, yet entrancingly set on Dartmoor, principally in the ruined castle keep of Lydford village and the gorge of the river Lyd . . .

“The Star-born” is enriched with many full-page wood-engravings by C. F. Tunnicliffe, whose design and craftsmanship . . . lend distinction . . .

[The very last paragraph reveals the reason for the somewhat obscure heading – it is referring to a new edition of The Old Stag (Putnam’s, 5/-) and the ‘tragedy’ is that of the red deer Stumberleap, swept away in the swollen river: based on a real ‘famous thunderstorm’ when the river rose many feet in an incredibly short time, and the deer was swept out to sea, along with of course 15½ couple of hounds.]

Birmingham Post (unsigned), 16 May 1933 (this short succinct review is quoted in full – the writer fully grasped (though a trifle overflowingly!) the essentials of the book and HW):

Knowledge, for Mr. Williamson, is the quest of human happiness and truth, and all the roads of his life have led towards that end. Step by step he has formed and manifested the belief that if we would restore our sense of eternal truths and elemental verities, the way lies not in the conservation of material things, but by conserving the spiritual home of all humanity and by the protection of living things – a belief that the countryside holds everything needed for the satisfaction of man’s wants, whether mental, physical or spiritual. All that most men make much of has little meaning for him, and throughout his works he has always professes the same active faith, crying of the inevitable ruin that awaits a busy though aimless generation which has learnt to control every force but the tumult of his own soul.

The “Star-born” is a final summation of his beliefs, and a broken-hearted lament because the Kingdom of Heaven is by no means at hand. An extravagant fantasy, conceived and executed with a magnificent integrity of feeling, it baffles description. One is tempted to leave it quiet, for to get the best from it the work needs to be approached in a spirit of sympathy and understanding equal to the author’s. Beyond the mere story are deeps of truth and a subtle beauty so gravely and delicately drawn as to be almost impossible of analysis. From the race of man a child is taken by Spirits of the Earth; he returns to bear the Light, living in human form on the Earth awhile. Failing in his purpose, and mocked and derided, he finally departs to join that immortal company of strangers who, likewise, suffered and were persecuted when carrying the Light among men. It is a strange spiritual adventure, rendered beautiful in a prose which has the essential quality of poetry and is an inspiration to all whose eyes are not closed to the world of simple things.

The very few reviews in the archive for the 1948 edition are thin and little more than a notification of the publication of this new work: however, it may be that others do exist?

*************************

A strange coincidence

A Dutton Broadsheet dated 14 July 1928 (these weekly ‘Book News’ broadsheets are 12” wide x 21” long) announcing (in an item at the bottom of the page accompanied by a photographic drawing) ‘HENRY WILLIAMSON WINS HAWTHORNDEN PRIZE’ included also the following item written by Duke N. Parry:

‘ARE THE STARS INHABITED?’

‘Sir Francis Younghusband Not Only Believes They Are But Says They Must Be’

This is in fact a review for Life In The Stars by Sir Francis Younghusband, who believed that these higher beings, being ‘finely sensitive to excellence they would be finely sensitive to evil’ – and ‘Music must play a fundamental part in the lives of these higher beings’, and much else. The reviewer ends: ‘the author thinks it possible that the life hereafter will carry men and women to life on the stars as their reward of virtue’.

This cannot have influenced HW’s own thoughts (The Star-born being finalised in 1924), but it is a strange coincidence here.

*************************

The cover of the 1933 limited edition, with the signed certificate:

The dust wrapper for the 1933 trade edition, featuring Tunnicliffe's marvellous wood-cut of a barn owl and skull, not printed in the book:

The 1948 revised edition:

Cedric Chiver's 1973 re-issue of the 1933 edition, published for the library market:

Back to 'A Life's Work' Back to 'The Pathway'