THE UNRETURNING SPRING

being

The Poems, Sketches, Stories, and Letters

of

James Farrar

Edited and Introduced by Henry Williamson

(Although this book was not written by HW he was solely instrumental in its publication, and it was of great importance to him. As such, it warrants a detailed entry within 'A Life's Work'.)

|

|

|

First edition, Williams and Norgate, 1950 |

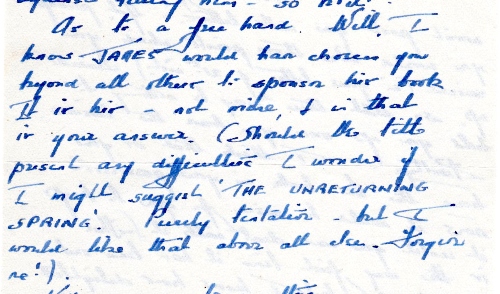

Appendix (pages from HW's draft Introduction)

First published Williams and Norgate,1950, 15s net

Chatto & Windus, 1968, 30s net

Friends of Honeywood Museum (Carshalton), new edition, 2008; with a new second introduction by John Monks, £9.00

Epigraph on the title page:

'And every day I, a curious boy, never too

Close, never disturbing them,

Cautiously peering, absorbing, translating.'

Walt Whitman

James Farrar was born 5 October 1923. His parents separated when he and his older brother, David, were still very young. (His father had served in the RFC in the First World War.) The boys lived with their mother in Carshalton, in south London, and James (known as Jim by family and friends) went to school in Sutton – the same area where both of HW's sets of grandparents had lived next to each other. This is an area described in detail in HW's early Chronicle of Ancient Sunlight novels, in particular the first, The Dark Lantern, but which, as they were written after his death, would have been unknown to Farrar.

When young Farrar left school, he went to work on a farm, Manaccan, in Cornwall, where he began to keep a journal containing his thoughts, poems, and prose writings. The Second World War broke out just before his sixteenth birthday and in early 1940 he returned to London, where he worked in an office, which he hated. At the age of 17½ he volunteered for the RAF, and was called up soon after his eighteenth birthday at the end of 1941. After training he passed as a Flying Officer Navigator: hence the 'N' on the badge in his photograph. The course of his RAF life can be traced through his writings. Interestingly he spent his last leave at the Manaccan farm, but cut it short on learning that the long-awaited invasion of France – D-Day, 6 June 1944 – had begun, and returned to his base and flying duties with 68 Squadron. In the early hours of 26 July 1944 the Mosquito in which he was acting as navigator went to intercept and destroy a VI flying bomb off the east coast, a highly dangerous procedure. Something went wrong and he and his pilot, Fred Kemp, were killed. Although the pilot's body was found in the sea, that of James was never recovered. He was three months short of his twenty-first birthday.

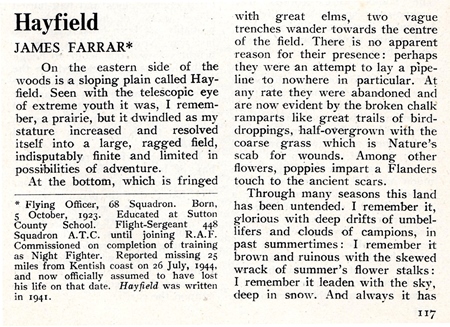

James Farrar first came to the attention of HW when John Middleton Murry, the editor of The Adelphi, began printing some of his work in the magazine which had been sent to him by the dead airman's mother, Margaret Farrar. 'Hayfield' appeared in the April–June 1946 issue; these are the opening two pages:

In this same issue HW had published the second part of his article 'The Sun that Shines on the Dead' – his thoughts on returning to the battlefields of the First World War (material from his The Wet Flanders Plain). It does now seem a poignant coincidence, but of course, for HW the war was never far from his mind.

It was the October 1946 issue of The Adelphi (Vol. 23, No. 1) that contained (from HW's viewpoint) the all-important 'The Imagination to the Wraith', a short prose item addressed to the 'Wraith': Willie Maddison of the Flax of Dream novels – and thus HW himself.

HW does not give the date that Jim (as he was always known) wrote this, but Christopher Palmer, in his Spring Returning: A Selection from the Works of James Farrar (1986; see Publishing history below), meticulously notes that it was 'Spring, Torquay, 1942.

One can imagine the shock HW must have felt on reading that: shock and then – what? – a profound emotion of empathy, of recognition of a like mind, a soul-mate? October 1946 saw HW at a very low ebb, as is shown in other entries in 'A Life's Work' covering this period (see particularly The Phasian Bird). War – death – loss – were foremost in his mind as he struggled to come to terms with the situation in the world and in his personal life. Unfortunately there is no copy of this particular issue in HW's archive, as there is no doubt that he would have written some comments in situ. It was sent to young Sue Connolly (Malcolm Elwin’s step-daughter, with whom at the time HW was enamoured).

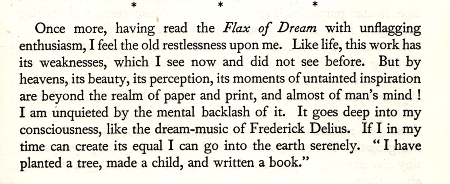

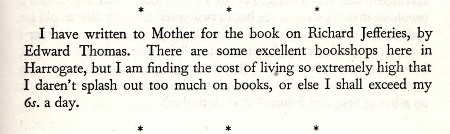

However, the effect of Farrar's work on HW can be seen by the comments he wrote in his copy of the next issue of The Adelphi (Vol. 23, No. 2, Jan–March 1947), containing Farrar's essay 'Pale Blue Windows'. The realisation that someone had read his work and believed in him as a writer gave him back his faith in himself as a writer.

This issue also contained HW's 'From a War-time Norfolk Journal: Easter 1944'.

(These Adelphi items are reprinted in Words on the West Wind, ed. John Gregory, HWS, 2000; e-book 2013.)

Apart from its references to himself, the extraordinary quality of Farrar's writing caught HW's attention. He contacted Murry for the source of the material, and then wrote to Mrs Farrar. From her reply and from what he read in the subsequent package of material that she sent him, he would have realised just how much this young man had revered him. Apart from recognising in this young genius an echo of his younger self, he also recognised that the world had lost someone who promised to be a great writer for the future. He determined to bring this work to the attention of the reading public.

The sensitive words of Christopher Palmer capture the link between these two men:

What, now, of this mystic communication between James Farrar and Henry Williamson? James believed that lines of force exist between people, as between poles of a magnet. . . . the composer whose music meant most to him, Frederick Delius – through the agency of his greatest and most influential literary love of all, Henry Williamson. It was first and foremost Williamson's work which stimulated Jim's urge creatively to write himself.

Palmer then quotes passages from Farrar's work as examples of this connection, particularly the extraordinarily powerful 'The Imagination to the Wraith'. Some of these passages are given later in this entry.

This all struck home to Williamson in the aftermath of the war, when he was at his lowest ebb, both mentally and physically: 'Therefore James Farrar meant much to me, and I felt at times that he was helping me. He gave me hope.'

So we come to the heart of the matter. The Farrar/Williamson relationship had some of the elements of master/disciple, but in certain ways was unique. . . .

Palmer relates that HW told Margaret Farrar in a letter that his American pilot in The Phasian Bird (1948) was akin to James, and described thus:

He was a young man punctilious and high-minded, with ambition to be a poet speaking for his generation as in a previous war Wilfred Owen had spoken for the generation of 1914‒18.

(However, it should be noted that there is more than one candidate for the role of that airman: see the entry for The Phasian Bird. HW was hardly aware of Farrar when writing that book, although he could have made some late amendments.)

When HW took over as owner/editor of The Adelphi, his first editorial (Vol. 25, No. 1, Oct‒Dec 1948) was titled 'The Lost Legions': a reference to his predecessor J. M. Murry and the dead of the First World War. He also devoted several pages to just one individual of the lost legions of the Second World War: James Farrar, incorporating further poems and essays. By that time, although there is no mention of this in his diaries, The Phasian Bird had been completed.

HW's personal life at this time probably had a priority. He married Christine Duffield in April 1949 and they went on an extended honeymoon to the south of France, where they stayed with with Richard Aldington at Le Lavandou. Their son was born in early May the following year, 1950. A second visit to France took place from 23 September to 18 October. Meanwhile he was working hard on The Dark Lantern, which needed several rewritings before he (and his publishers) were happy with it.

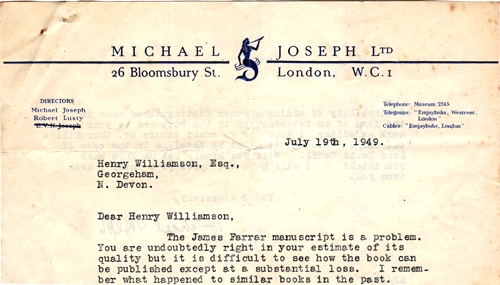

Finding a publisher for the projected Farrar book was not without problems. Whether HW approached Faber is doubtful, due to his recent rift with Dick de la Mare. But a letter from Michael Joseph (signed by the man himself) shows it was turned it down by this publisher.

Michael Joseph went on to say that he would like to publish the book, but only if HW could obtain Winston Churchill or Lord David Cecil to write an Introduction, noting that he doubts either would be interested.

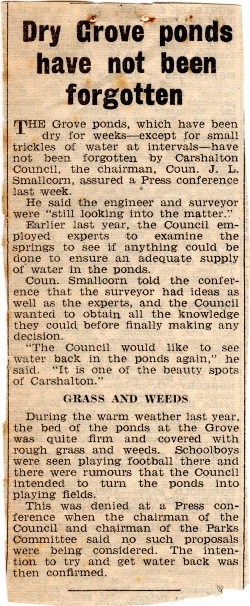

HW sent the letter on to Margaret Farrar, and in returning it she enclosed the following cutting: this is 1949 – only four years after the war ended, with such horrendous loss of life in every district of the land.

A memorial for the dead of the Second World War was at last erected in 2014: until then the original First World War memorial served for both wars.

Palmer relates the next step in the publishing saga:

A member of the London publishing firm of Williams and Norgate looked out of his office window and saw Henry Williamson walking up the street with what was obviously a great pile of manuscripts. He ran down and introduced himself . . .

Apparently HW was on his way to see another publisher, but handed over his package there and then. (One wonders to which publisher he was on his way!) This person was Jon Wynne-Tyson, who worked for various publishers before setting up his own private firm, and who had a peripheral acquaintanceship with HW – but whose main claim to fame is that he (briefly, as it was contested by others!) became the King of Redonda after the death of John Gawsworth, the self-styled King of Redonda. (See HWSJ 47, September 2011, Anne Williamson, 'Following a Wild Goose Chase: HW, the King of Redonda, and Wilfrid Ewart's Way of Revelation', pp 85-99.)

A letter from Williams and Norgate, signed by Philip Inman, a director, shows they saw the worth and potential of the book:

A further letter confirms the arrangement:

Margaret Farrar's response, dated 23 January 1950 shows her happiness:

And again she included a cutting from her local newspaper for HW's interest.

There is no mention of the occasion, but the book was published (by deduction) in November 1950.

************************

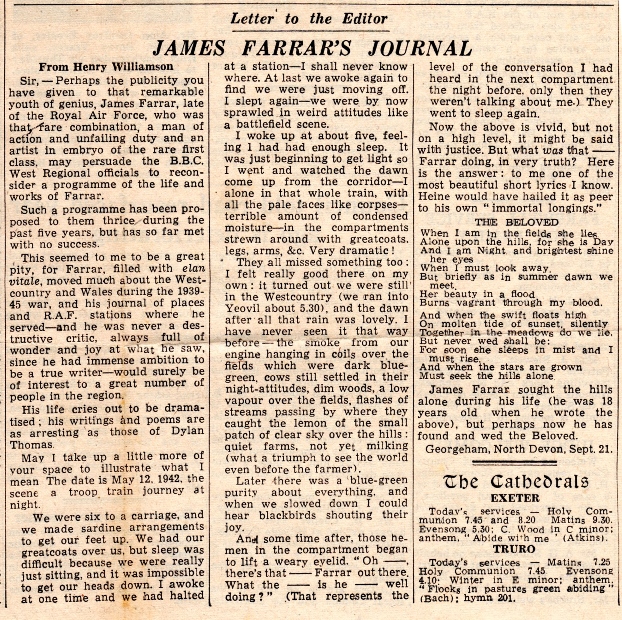

Apart from the work involved with the actual book and its editions, HW also over the years took other opportunities to further Farrar's work. For instance, this undated cutting, although no source is mentioned, is most probably from the Western Morning News:

Another example is HW's tribute in the April–June 1959 issue of Poetry Review.

Palmer quotes HW from a BBC Radio 4 tribute to James Farrar: The Unreturning Spring (with David Heycock) first broadcast in July 1967, as saying:

Farrar could write anything he saw; and he'd get it right. He saw it with delight, with great interest, with understanding; and he could penetrate … He had the divining mind; and the divining mind is the God-like mind.

HW's diary records on Monday, 19 June:

B.B.C. 2.30, James Farrar, record at Hut. Heycock – BBC Bristol.

Otherwise there is no mention of it, and HW made no comment about the actual broadcast itself.

It is also known that in his later years HW read some of Farrar's work at his very popular 'Readings' at the Lobster Pot in Instow, Devon.

Margaret Farrar (1896-1986) was indefatigable in her tenacity to get her son's talent recognised. One can see that this was for her – most understandably – a way to keep her son's essential spirit alive. She must have felt that fate had at last been kind when the man her dead son had revered above all other writers contacted her about his writing, and she was very happy to hand everything over to HW. The immediate correspondence from her shows her gratitude for HW's interest and work on her beloved Jim's behalf. And she was very happy with the finished result. However, by the time HW proposed a new edition in the mid-1960s – by which time I was personally involved to some extent with his work – he had become very irritated with what he considered her interference in the professional matters involved in publishing. Her ideas clashed with his own, sadly causing HW great aggravation: no doubt the irritation was mutual! (As can be seen she was more or less the same age as HW. Circumstances – and her nature – made her a very strong-willed lady, allowing her to face life with courage and fortitude.) One senses here and there in his writing that at times James also found her a little overbearing.

All of James Farrar's archive was deposited at Exeter University, so it is possible to consult it alongside that of HW held there.

*************************

The scans of the Contents and Index above (the Index is from the second, Chatto & Windus, edition) will give a considerable idea of the scope of the work contained in Farrar's book. The material is presented simply, in chronological order, and so one moves from poem to prose, notes, personal observations, journal-like entries: giving a kaleidoscope view of the fresh, observant and sensitive mind of this young man.

The title of the book was chosen by James' mother from the title of one of her son's prose essays: 'Spring Returning, 1944' (p. 220) written shortly before his death. Her letter is dated 22 July 1947:

It will be clear from the extracts given further on that the piece would have had particular resonance for HW. Palmer tells us that Farrar derived that title from a poem by Laurence Binyon –

'The Unreturning Spring'

A leaf on the gray sand-path

Fallen, and fair with rime!

A yellow leaf, a scarlet leaf,

And a green leaf ere its time

Days rolled in blood, days torn,

Days innocent, days burnt black,

What if the wind is sighing

As the leaves float. Swift or slack?

The year's pale spectre is crying

For beauty invisibly shed,

For the things that never were told

And were killed in the minds of the dead.

Binyon (1869-1943) is the poet who wrote ‘For the Fallen’, first published in The Times on 21 September 1914. One of its verses has become synonymous with the British act of remembrance for the war dead:

They shall grow not old as we that are left grow old:

Age shall not weary them, nor the years condemn.

At the going down of the sun and in the morning

We will remember them.

The epigraph on the title page of the book is also written at the front of Farrar's manuscript Journal (it is interestingly comparable to HW's 'Richard Jefferies Journal' and his quotation on 'Ancient Sunlight' – this would not have been lost on HW):

And every day I, a curious boy, never too

Close, never disturbing them,

Cautiously peering, absorbing, translating.

The words are from a poem (in amazingly modern idiom) by the American poet Walt Whitman (1819–1892), the 'Out of the Cradle Endlessly Rocking' part of the section 'Sea Drift' (which contains various poems about the sea and the sea-shore) of his major work Leaves of Grass – originally published in 1855 as twelve poems, with several revised editions until definitive version, published just before his death, of 400 poems. The poem here comes from Whitman's second period, which encompasses the prevailing themes of love and death.

I have not found anything in HW's archive to suggest he was personally aware of Whitman's work. But it is interesting to note that Whitman's experience as a volunteer nurse and correspondent for the New York Times in the American Civil War affected him in much the same way that HW's experiences in the First World War affected his own psyche: the problem of reconciling the destruction of war with a visionary idea of their respective countries.

It is somewhat chilling to find that at the end of this long poem about love and loss (using the American mockingbirds as his medium) the 'curious boy' asks the sea to tell him the all-important word:

Whereto answering the sea,

Delaying not, hurrying not, . . .

Whisper'd . . .

Lisp'd to me the low and delicious word death,

And again death, death, death, death,

Hissing melodious . . .

Death, death, death, death, death.

As a navigator engaged in combat, James Farrar must have been only too aware that 'death' was the 'all-important word'. It is sadly ironic that he chose this poem to head his intimate journal. But, like HW, he obviously had a deep interest in the concept. But the most important – perhaps the only – aspect here for Farrar was that a selection of the words from Whitman's 'Sea Drift' section were set to music for orchestra, baritone and chorus by Frederick Delius in one of his greatest works, Sea Drift (1903).

**********

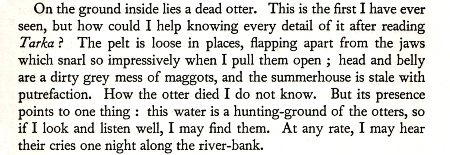

As the pieces in the book are not HW's – and should be read by those interested for themselves – I do not intend to analyse them here. However, to show how closely Farrar was influenced by HW, here, scanned from HW's own copy, are some extracts which concern HW, with some others that would have struck a particular chord with him.

Page 45:

Pages 48/49:

Page 119:

Pages 123/4:

Page 151:

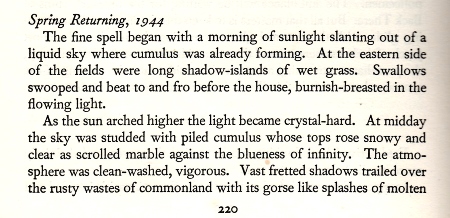

Page 220: 'Spring Returning, 1944' (24g)

'Spring Returning' spans 5 pages; here is another extract, from pages 222/3, with HW's markings:

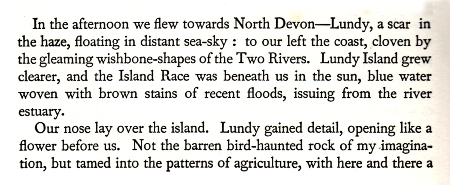

On the pernultimate page 241, HW introduces the last two pieces with this note:

HW ends the book with 'The Imagination to the Wraith', already reproduced earlier, but does not date it. Palmer marks 'Wraith' as 'Spring, Torquay, 1942', so it should really come fairly early in The Unreturning Spring. James Farrar was posted to Torquay on 7 March 1942 – and so obviously it comes immediately after the entry on page 63, where he writes that despite barbed wire he has been able 'to get down to the sands' and 'was very happy at sunset'.

A short while after writing this Farrar wrote a short poem entitled 'Death' (it appears on page 80):

The last actual entry that James Farrar wrote is a little disturbing in both its content and context. Titled 'The Dream', it relates a flying incident that involves death of an enemy by shooting: rather frighteningly prophetic. Farrar added notes that he made about his thoughts after he woke up. Underneath the notes HW has written 'Farrar's End' in red ink:

It seems appropriate to end with the words that Palmer ends his book with: a reference to Delius' Requiem' (1915) which was dedicated:

To the memory of all young artists fallen in the war-service

Palmer notes here HW's feelings for soldiers of both sides after his experience in the war and Delius' own conflict of feelings being of German origin. (He would have been unaware in 1986 of HW's own German ancestry.) Palmer feels that the work stands as a requiem for James himself – who apparently did not know the work, as it was more or less ostracised by the powers that be – as its

finale blesses the eternally renewing power of spring, of spring returning.

Eternal renewing . . .

*************************

|

|

1950. The Unreturning Spring was first published by Williams and Norgate in 1950, probably November, priced at 15 shillings (75p). That HW asked, in vain, for a reprint after the edition had sold out is seen in the following letter from the publishers:

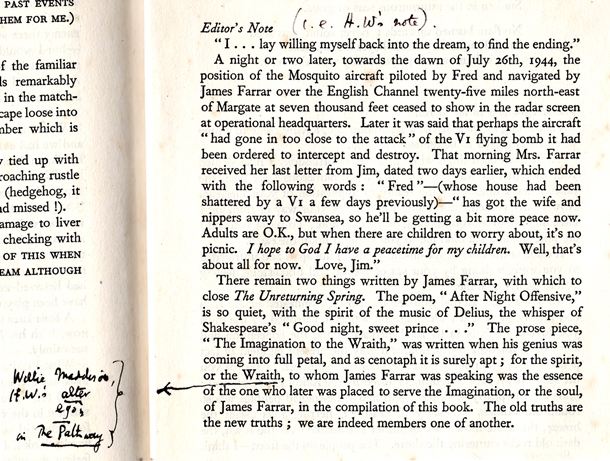

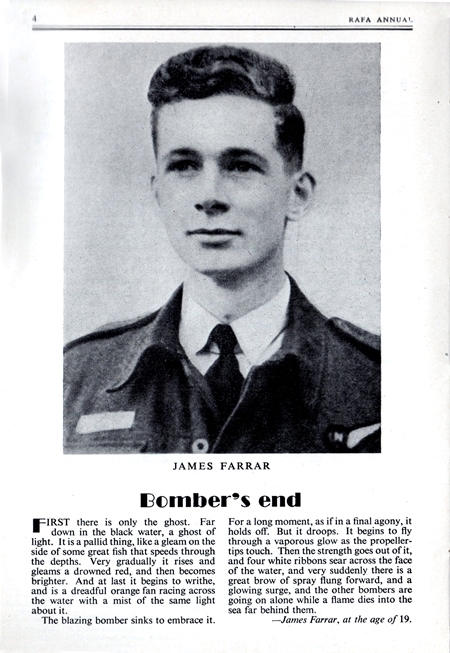

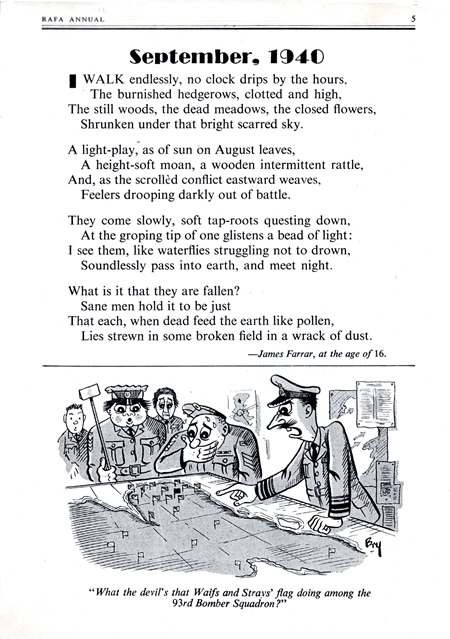

Undoubtedly in order to create some interest, HW then evidently contacted the Royal Air Force Association, which responded in magnificent fashion, as seen in the following extracts published in the 1952 RAFA Annual. The editorial foreword is particularly poignant.

Further items appeared on p. 46, the poem 'Airman's Wife'; pp. 47/8, the story 'Anson'; and pp. 62/3, 'Cloudy Dawn on Station Defence'.

This publicity still did not result in the reprint that HW desired, and some years passed before a new edition appeared.

**********

|

|

1968. Chatto & Windus published a new edition in 1968, price 30 shillings (£1.50), and the subtitle was simplified to ‘being The Collected Works of James Farrar’. In essence it was a reprint, as it used the same typesetting for the main text as the first edition.

The quotes on the back of the dust cover are the same as the ‘advance opinions’ given on the back cover of the first edition.

HW took the opportunity of making some revisions in his 'Introduction', though these are fairly minor. He omitted the list of names from the first paragraph, and on page 9 he omitted reiterating the words of the Walt Whitman quotation on the title page – words written by Farrar himself on the front page of his journal, in which he wrote most of his work. We learn that the title was chosen by the airman's mother, Margaret Farrar, by turning round the title of one of her son's essays, 'Returning Spring'.

On page 10 HW has interpolated a comparison with Wilfred Owen, the First World War poet who was one of HW's main sources of inspiration.

(This version of HW's Introduction is reprinted in Threnos for T. E. Lawrence and other writings compiled and edited by John Gregory, HWS, 1994; e-book 2014.)

A further addition was an Index at the end of the book (reproduced earlier), which helpfully lists the actual contents.

**********

|

|

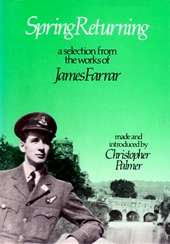

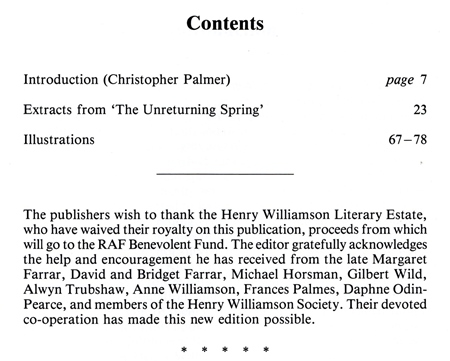

1986. Spring Returning: A Selection from the Works of James Farrar, Autolycus Press

Made and introduced by Christopher Palmer, with 12 pages of photographs and reproduction of sketches by Farrar himself

This further edition of Farrar's work was selected by the musicologist Christopher Palmer, some years after HW's own death. This had of course nothing actually to do with HW – but it arose because of HW, and contains information that needs recording here. Palmer, in the spirit of perpetuity – or immortality – chose to link his collection to the earlier editions by using the title of Spring Returning, after Farrar's eponymous essay.

Palmer dedicated his book to:

(JF – James Farrar: HW – Henry Williamson: FD – Frederick Delius)

In homage to, and as a mark of respect for, Farrar's war-service in the RAF, all royalties from this edition were donated to the RAF Benevolent Fund – an appropriate and worthy charity.

Christopher Palmer (1946-1995), writer on musical matters, orchestrator and arranger, was an eminent and respected musician and music critic, particularly interested in impressionist music (in 1973 he published Impressionism in Music). He also compiled an anthology of the prose of Arthur Machen – so making a further link with HW, who knew Machen in his short early 'Fleet Street' period and had written a brief memoir of this era. At the time of publishing this book on Farrar, Palmer became a member of the HW Society.

The origin of Palmer's book derives from a BBC Radio 4 programme that he presented: Spring Returning, broadcast on 8 May 1983:

(The programme was reviewed by John Homan, then Secretary of the HWS, in HWSJ 8, October 1983, pp 44-47. Palmer subsequently gave a talk based on the programme to the HW Society Spring Meeting in Lewisham, Spring 1984. Palmer's book was reviewed in HWSJ 15, March 1987, p 53.)

This is a most useful edition, as Palmer's 'Introduction' acts not only as a sensitive biography of James Farrar but also contains insight into the spiritual connection between the dead airman's psyche and HW – 'friends in ancient sunlight'; and then connects both men to the impressionist composer Frederick Delius (1862-1934). This reveals a potent mystic connection between the three men.

HW had attended a very early performance of Delius' A Village Romeo and Juliet at Covent Garden in 1920, which made a lasting impression on him, especially the poignantly tragic 'Walk to the Paradise Garden' – the inn from whence the thwarted young lovers take out a boat and remove the plug from the bottom, thus committing suicide by drowning. 'Drowning' was a theme in HW's work (see, for example, The Pathway and The Gold Falcon), and it was already recognisable within Farrar's work: water being a symbol of purification. Delius was certainly one of HW's most loved composers, and he chose Delius’ rendering of Ernest Dowson's poem Cynara as one of his records in his Desert Island Discs programme. Farrar indicated that his love for Delius' music stemmed from the influence of HW.

Palmer's book is further enhanced by the selection of photographs, which include reproductions of Farrar's own sketches, revealing he was also a quite talented artist.

As an example of HW's thought and effort on behalf of other similar writers, Palmer mentions that HW also edited V. M. Yeates' Winged Victory and also edited and wrote an introduction to Walter Robson’s Letters from a Soldier (Faber, 1960) (entry forthcoming).

***********

|

|

2008. A new edition was published by Friends of Honeywood Museum (Carshalton), priced at £9.00. This is as the original first edition, preserving HW's 'Introduction', but with a new second Introduction by John Monks, who was also responsible for seeing the book through the many stages of production.

The Preface by Monks explains how and why the new edition came about: basically, that as a son of Carshalton and former pupil of Sutton County School, Farrar was not receiving the attention that he deserved.

The new editor dropped the original Walt Whitman quotation, and instead taken one from Farrar's own writing:

John Monks’ Introduction is superb: the reader learns a great deal of previously unknown information about Farrar, with many previous nebulous details fleshed out and some uncertainties clarified. There are also several interesting comments about HW.

The book is altogether a valuable addition to the Farrar story.

*************************

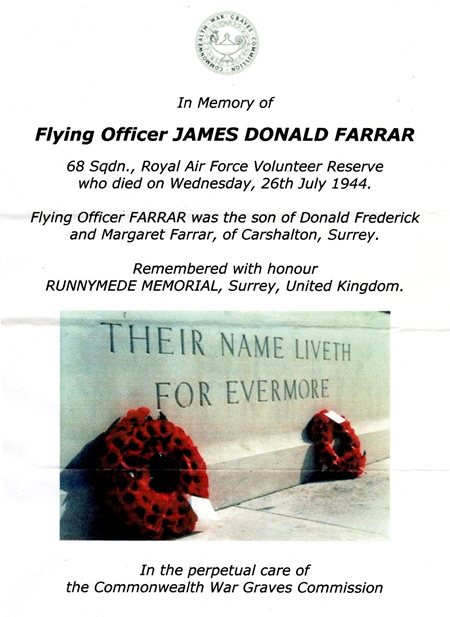

James Farrar is officially commemorated on the Runnymede Memorial, at Englefield Green, near Egham, Surrey. The memorial, designed by Sir Edward Maufe, is dedicated to over 20,000 Commonwealth Air Forces personnel, including those with acting RAF, AuxAF or WAAF rank such as SOE operatives, who lost their lives in the Second World War and have no known grave.

Farrar's last flight was made from RAF Waltons Park, Saffron Walden, near Audley End (this presents a small puzzle, for 68 Squadron was based at RAF Castle Camps between 23 June 1944 and 28 December 1944; perhaps RAF Waltons Park was a satellite airfield, though no record has been found of this). In one of Margaret Farrar's letters to HW she enclosed this cutting:

*************************

Go to Critical reception, Appendix, and Book covers

*************************