Back to The Innocent Moon main page

Critical reception:

The Bookseller, 28 October 1961:

One of Macdonald's advertisements for the book:

And another, eye-catchingly set vertically in the Sunday Times:

Sunday Times, 1 October 1961:

MORE AUTUMN BOOKS. Publisher’s Pick – Part II

[Publishers select one particular book from their own forthcoming lists – about 25 here]

E. R. H. Harvey (Macdonald) [Eric Harvey was the publisher's managing director]: My personal choice is “The Innocent Moon” by Henry Williamson. This romantic novel of the early 1920s has an idyllic quality that should prove particularly refreshing today, ans for me it has the special appeal of being largely set in the West Country. “The Innocent Moon” also marks the latest stage in the growth of that revealing sequence of novels to be known collectively as “A Chronicle of Ancient Sunlight”, which I regard as among the most remarkable and evocative ventures undertaken by any living author.

Evening Standard (Walter Allen), 31 October 1961:

The Scotsman, 4 November 1961:

Phillip Maddison emerged from the 1914-18 War having, as it were, stepped for a time off the ladder of life, feeling deprived of his personality by the overwhelming powers of destruction. In The Innocent Moon tentatively at first, he resumes the ascent. . . .

This book . . . is a work of great breadth and beauty, and is also a classic illustration of the power and scope of the novel. . . . most impressive is the completeness of the structure, the steady portrayal of Phillip [moving from nature to human relationships].

Sunday Telegraph (Anthony Quinton), 5 November 1961:

"The Innocent Moon" is the sixth in the series of Henry Williamson's Phillip Maddison novels, and conducts the hero through his middle twenties and the century through its early ones.

It resembles the scene presented by a long-deserted attic, full of forgotten umbrella-stands, cloche hats, badminton rackets and rusty skates. The immense tide of minor incident and chat rolls by, enthusiastic intellectuals posture and declaim, a series of distinctly young girls disturbs Phillip's heart, the substance is thickened with long diary entries weighted with chunks of "nature".

A painless and even pleasant process, it does not seize the attention: Phillip is too watery, unformed and negative a figure and the events he is involved in are too radically inconsequent. Mr. Williamson's memory is too much in evidence and his judgment not enough.

Sunday Times (Alan Wykes), 5 November 1961:

. . . like his creator, Phillip Maddison has an impressive individuality. Mr. Williamson’s . . . grasp of period, place, and character throughout . . . is masterly. It is impossible to criticise him for his oddities . . . To read this particular volume is to enjoy a bright clear picture of the twenties: but to follow Mr. Williamson through all the tones and tempers of his chronicle is to emerge with a sense – insistent and triumphant – of having been brushed by experience. Follow him.

The Spectator (Patricia Hodgart), 10 November 1961:

Mr. Williamson’s view of history is strictly a personal one, and in The Innocent Moon he adds another long novel to the sequence called, for some reason I have not discovered, 'The [sic] Chronicle of Ancient Sunlight'. This one continues the career of Phillip Maddison, newly returned from the 1914 war and set on becoming a writer. He tries London literary life for a bit:

'Do you like Conrad?' he next asked a very quiet woman standing alone. She had gentle brown eyes, and a fringe over her forehead. 'Yes,' replied Miss May Sinclair, simply. 'And do you love Francis Thompson?' he asked eagerly. 'A beautiful poet,' she replied. He felt safe with her.

After a few paties like this, where hostesses chase lions, he retired to Devon to write, only to find the landscape enlivened by a procession of constant and inconstant nymphs, teenagers of the Twenties who tease him out of thought and as often as not on to the tennis court. ('"Care for a knock-up?" asked Annabella [sic], raising her eyebrows slightly.') Mr Williamson is gently ironical and often very interesting about the literary life of the period, and as finely observant as ever of the birds, beasts and flowers of Devon, but Maddison and his tremulous love-affairs are hard to swallow.

Bristol Evening Post (Michael Hardcastle), 10 November 1961 (7 column inches):

It’s 1920 – and the horror still haunts Maddison. Still they come, those long, brilliant, enthralling, evocative books by Henry Williamson about the life and times of Phillip Maddison, a hero of the Great War and now an unsettled civilian. . . . Phillip is still restless, hyper-sensitive, introspective and becoming gradually more egocentric . . . haunted by the horrors he experienced on the Somme.

The Bookseller (O.P.), 11 November 1961:

The Innocent Moon . . . is set in part against a background of the literary world in London after the first war. This background has all the appearance of verisimilitude and I foresee a good deal of innocent research for those who like to have their literature and life neatly equated. . . .

The Observer (John Davenport), 12 November 1961:

[The mention that Mr. Williamson’s ‘R.A.F. novel is a masterpiece’ – clearly confusing him with V. M. Yeates, author of Winged Victory – shows that the reviewer is perhaps not entirely reliable!]

The Times Literary Supplement (Walter Keir), 24 November 1961 (the review was combined with Edgar Mittelhozer's The Piling of Clouds and Alex Comfort's Come out to Play):

These three novels are about sex. Mr. Williamson's, however, much less exclusively than the others . . . and "The Innocent Moon" is pretty much what that suggests, lovers walking the harmless and romantic lanes, observing nature and the birds and the bees and the flowers, but emulating them no further than by an occasional caress . . . With "The Innocent Moon" we reach the ninth volume of Mr. Williamson's series of novels concerning the adventures of Phillip Maddison and are still only as far as the 1920s. Here Phillip, after a brief spell in Fleet Street, retires to a cottage in Cornwall [sic] to write and generally work things out. Here also he keeps a diary, extensively quoted, consisting largely of nature notes. There are also occasional visits to London and abroad. And there are also, of course, his love affairs, if one can so call them, all of them fragile, tenuous and bloodless, very different from both Mr. Mittelhozer's forced horrors or Dr. Comfort's forced hilarity.

The result is a curious mixture. On one page we will find this:

"March 21. A wonderful day. The bees were climbing over the lesser celandines . . . tame bees. The flowers were bright with sundust, varnished and gleaming, stained at the hub, as it were, of their spoke petals . . . Cock blackbirds strutting in the grass. Spider gossamers gleaming in the sun. Violets out . . ."

And so on at length. On another level there is a lot about the literary London of the time:

"I met a dark vivid girl at this meeting. After the lecture, given by a bank-clerk poet called Eliot, we talked . . . she is quite the nicest person I met there, and she loves the wild things."

The love scenes themselves involve a great deal about the wild things, introversion, quotations from poets such as Francis Thompson.

This is an unashamedly old-fashioned novel. Many readers will also find it a touching and nostalgic one.

Express and Echo (Exeter), 10 November 1961 (10 column inches):

PHILLIP MADDISON COMES TO DEVON

The publication of . . . is the most important recent event in the world of books. . . . the disillusioned young ex-officer lingers for a while in Fleet Street newspaperland and “literary circles” and has an attachment to an idealistic young woman, makes an abrupt departure for the simple life in Devon. . . . there is a large element of himself in most of Williamson’s novels . . . To read this saga . . . is an experience which cannot but leave an indelible impression on the mind. In particular the novels about France and life in the trenches belong to the great literature of the war.

A prolific writer [nature classics] . . . But the present sequence . . . may well be judged by time to be even more important. . . . [a greatly undervalued writer].

Herald & Express (Torquay, Devon), 16 November 1961:

Time and Tide (Gillian Tindall), 16 November 1961:

A novel with no relevance to today . . . family sagas . . . are out of fashion; but Mr. Williamson is as undisturbed by literary fashion as in the West Country of which he writes. . . . This book is not only about a vanished world but its style belongs to it. . . .

I think, over fifty years later, we might find that quite complimentary – but it brought forth a letter from Father Brocard Sewell to HW, supportive as ever:

Western Morning News (Plymouth, Devon), 17 November 1961:

With each new volume added to the series . . . reduces the challenge of anything comparable in all literature. . . . This work is not based on a plot. It is a sequence of events . . . the story depends on an extraordinary representation of character. . . . [compared to the often (superficial) cartoons of Dickens] are seen to embody deep inner forces originating from their earlier times.

Topic, 18 November 1961 (10½ column inches):

[After an opening paragraph of general information, which includes one or two errors of fact:] In his sixties Williamson is writing with a plain-spoken vigour . . . He is not given to autobiographical gossip . . . but his life may be assumed to have been put into his novels. . . . in a series which ought to be valued at least as highly as The Forsyte Saga [I would remind you that Galsworthy & HW were, unbeknown to each other, actually cousins.] It is funny and touching and superbly honest . . . The idealism, the nightmares, the shynesses and the jokes are quietly and lucidly reported . . .

Birmingham Post (Geoffrey Bullough), 21 November 1961:

There are two poets in Henry Williamson’s THE INNOCENT MOON, or, rather, three, for Willie Maddison is a modern Shelley, Phillip his cousin is a modern Richard Jefferies, and Mr. Williamson is behind them both . . .

Yorkshire Post (A.B.), 23 November 1961:

. . . It is satisfying to know that the modern English novel is capable of vast Proustian structure. . . . Phillip Maddison, rather like the young Wordsworth, is concerned with controlling (and being drawn to self-fulfilment by) the headstrong troika of art, nature, love. . . . May this chronicle long continue.

Eastern Daily Press (Doreen Wallace), 23 November 1961:

Book Eleven [sic] . . . Phillip . . . is trying to break into the literary world and into love. It takes 313 pages. The 1920s background is carefully done; real people appear thinly disguised . . . but Phillip has already had enough words expended on him . . . and is far less interesting than otter or salmon.

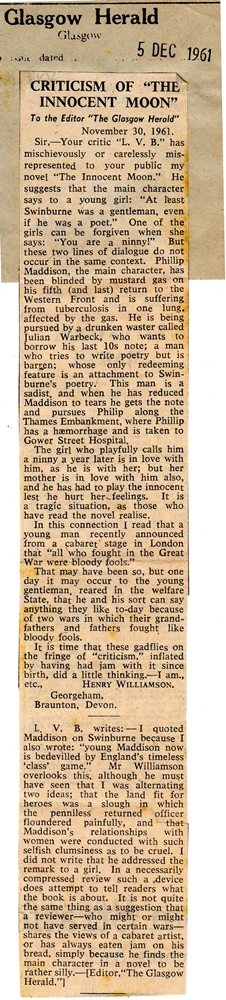

Glasgow Herald (L.V.B.), 23 November 1961 (2½ column inches only):

The Innocent Moon by Henry Williamson, the ninth instalment in the saga of Phillip Maddison, finds the young returned officer trying to become a writer in the Britain which was to be a land fit for heroes. Except when he is writing about the countryside, young Maddison now is bedevilled by England's timeless "class" game and in addition is a girl-hungry simpleton.

He goes on the agonising Bohemian walking-tours of the day, he sees girls as impossible bits of dreamery, and can say:– "At least Swinburne was a gentleman, even if he was a poet." One of the girls can be forgiven when she says:– "You are a ninny!"

This item included only because it evoked a rather scathing letter from HW (though why this review in particular, one wonders?):

Daily Telegraph (Daniel George), 24 November 1961:

Henry Williamson has now reached the eighth volume in his sequence of novels concerned with the novelist Phillip Maddison. Still in the years following the 1914-1918 war, Phillip pursues his chequered literary career under "The Innocent Moon". A memory that can take in the 1920s will patiently accommodate itself to this chronicle of apprentice authorship and romantic love. Long-forgotten names (Netta Syrett, May Sinclair) leap from the page in company with transparently disguised names such as Mrs. Portal-Welch (known as Sappho), Septimus Petal, head of the publishing house of Hassels, and J. D. Woodford, adviser to Hollins.

Phillip kept a diary, and we are treated to long extracts from it. They are what in other circles at that time would have been called shy-making. Even outside the diary and under the wing of the author he can be terribly literary, capable on his honeymoon of remarking to his bride: "There is something strange about the moon. I really think it has a power upon the spirit of all things on the earth. Do you know the books of Rudolph Steiner?"

The trouble is that Phillip is always in character – a dedicated aspirant to literature, devoid of any sense of humour. Looked at like that, he is portrayed with remarkable accuracy, and interest in him can revive when it seems at its last gasp.

John O’London’s (Harry Hearson), 31 November 1961 (8 column inches):

. . . Phillip Maddison is endeavouring to establish himself as a serious writer and is haunted by his memories of the battlefields. [Wide variety of place and character] . . . [but to whom] it would be impossible to extend [sympathy].

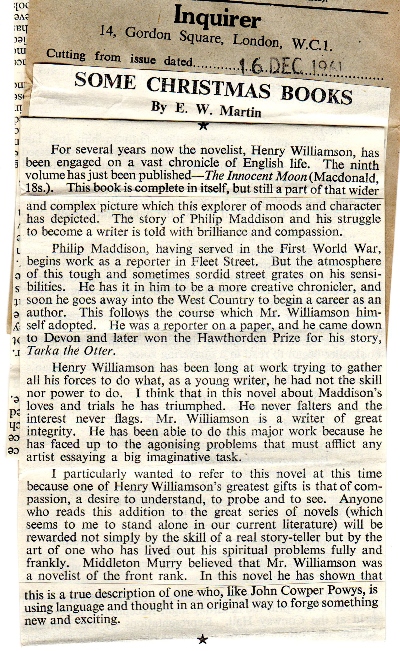

Inquirer (E. W. ‘Ernie’ Martin), 11 December 1961:

Irish Times (R.M. Gamble), 16 December 1961 (9½ column inches):

The immense autobiographical novel sequence . . . [this volume] corresponds closely to The Flax of Dream novels . . . many incidents are similar . . . [various criticism of ‘unabashed romanticism’ and the diary entries – BUT:] . . .

As the chronicler of an age he has an eye for the significant detail and incident that is not far short of Proust’s. . . . But he [HW] is now out of tune with the times . . . The world has gone in a very different direction. Phillip . . . is a misfit in more senses than one.

Manchester Guardian Weekly (Sid Chaplin), 7 December 1961:

This interesting piece also appeared elsewhere, but the source is not marked.

North Devon Journal & Herald (F. H. A. Kempe), 7 December 1961 (8½ column inches):

AND SO CAME PEACE

Williamson adds to his saga

[An opening paragraph recaps previous volumes.] Maddison having endured these horrors, is now trying to find his way in a literary career, initially as a reporter . . . [but] has too much intelligence to cultivate the trivial and too much integrity. [so to Devon] . . .

Perhaps the sense of anticlimax is inevitable, for Phillip, having survived the rigours that went into winning the war, is here living through the years of imperceptions which were to cost us the peace.

Homes and Gardens (Celia Dale), April 1962:

. . . The book has a strange wandering beauty about it, a rootlessness that at last comes to rest, which well recreates the lost generation that survived the First War.

The Aylesford Review (Ruth Tomalin), vol. IV, no. 5, Winter 1961-62:

In the same issue Macdonald took out a full-page advertisement: