LAP 2: Two wheels plus an engine (Nortons)

LAP 3: Four wheels (Peugeot to Alvis Silver Eagle, via Auto Union)

Appendices: The Alvis Silver Eagle (photographs); and Adventures with Alvis Silver Eagle DR6084, by Alex and Elspeth Marsh

LAP 4: Moving up a gear (Aston Martin to MG Magnette)

Appendices: Tale of a Two Litre; and Aston Martin Statement

LAP 5: The car that never was (Bédélia)

LAP 3

Four wheels

With sales of Tarka the Otter going well, HW finally sold the Norton and bought a second-hand 6-horsepower Peugeot. There is little information about this car other than a letter from a gentleman living in Benfleet, Essex, obviously involved in its purchase in some way, dated 28 September 1928, in which he states:

Dear Williamson

I am so glad the Peugeot is a success – my friend at Auto Auctions has always kept faith with me & it is gratifying to find one engaged in the nefarious trade of cars as sincere. . . .

|

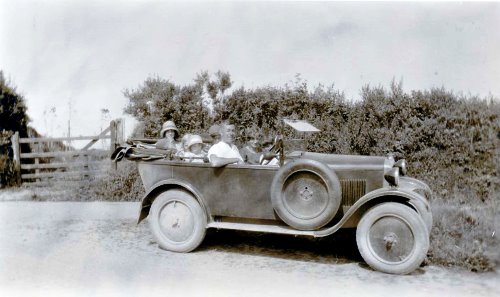

| HW at the wheel of his Peugeot – the passengers are unknown |

Another archive photograph of the car has a note by HW on the back:

My first car 6 horse-power Peugeot with G.B.S. on Exmoor 1928.

The identity of ‘G.B.S.’ is not known – it is not, as might be thought, George Bernard Shaw (whom HW did meet briefly in 1920 when GBS gave a talk to the Tomorrow Club, a literary club for promising writers that HW joined) – but I think that it may possibly be a quite extraordinary character (prone to drink) called Cecil Bacon who worked for HW and appears as ‘Coneybeare’ in The Children of Shallowford and ‘Rippinghall’ in the later volumes of A Chronicle of Ancient Sunlight.

HW noted that at the end of October 1928 he drove his wife to Braunton Nursing Home in the Peugeot for the birth of their second child, born according to HW, on the same day, 28 October, that his book The Pathway (volume 4 of The Flax of Dream) was published – but only recently I discovered John was actually born on the 29th. HW’s version made a good story though!

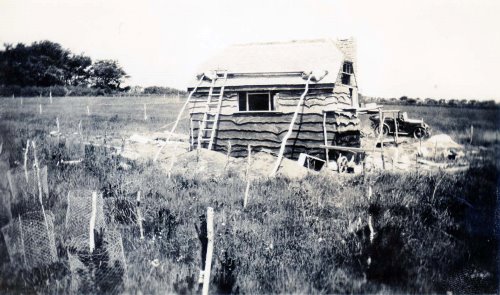

HW did not keep that Peugeot very long, as there is a photograph of another car in his newly-bought Field at Ox’s Cross at the time his Writing Hut was being built, which was 1929:

Cropped from this general view of the half-built Writing Hut, the car can be seen to be a 1928 ohc Morris Minor.

There are no details about this car in the archive, but at the end of 1930 HW left for a prolonged visit to the United States. A letter to his wife after he arrived there urges her to ‘get out and about in the Morris’.

There is one further story to relate before HW left Georgeham and moved to Shallowford, a substantial cottage on the Castle Hill Estate of Lord Fortescue, at Filleigh on the southern edge of Exmoor; it was Lord Fortescue’s brother who had written the Introduction to Tarka.

At the end of 1927 Tarka the Otter had been brought to the attention of Lawrence of Arabia – T. E. Lawrence – then stationed in northern India, by the critic Edward Garnett. TEL wrote a long letter back which included a list of criticisms of particular words and phrases (he apparently thought it was the author’s first book), but ending that he had ‘sizzled with joy’ on reading it. Garnett forwarded this letter on to HW. HW replied to TEL, sending a copy of another book, The Old Stag. The subsequent friendship between the two ex-soldiers was conducted mainly through an extensive correspondence, but there was one very significant meeting.

As is well-known, TEL was a very keen motorcyclist and owned a series of Brough Superiors, which he rode hard and fast. These splendid motorcycles were the brain child of George Brough (1890–1970), whose works were in Nottingham. The two men were quite close and indeed it is understood that Brough actually gave TEL some of the machines – or at least sold them at a huge discount. (It is also thought that the wife of George Bernard Shaw also provided the money for at least one of these motorcycles.) TEL owned a total of eight of Broughs: he named the first model (1922) 'Boa', after Boanerges (the son of Thunder), but the rest were all named 'George' – I (1923); II (1924); III (1925); IV (1926); V (1927); VI – UL 656 (1929); and VII – GW 2275 (1932) the one on which he was fatally injured in May 1935. ‘George VIII’ was at that point in the process of being manufactured.

Once TEL returned from India he was stationed at Plymouth, South Devon – within motorcycling distance of HW in North Devon. The two men planned a meeting, but for various reasons this kept getting delayed. However, on 28 July 1929 TEL got astride the current machine and, as HW relates in his book Genius of Friendship, as the church clock struck 12 noon Lawrence appeared on his nickel-plated motorcycle in the lane outside Vale House in Georgeham. No doubt they heard him coming – the sound of that powerful engine would indeed have reverberated like thunder through the narrow lanes leading to the village.

Knowing TEL’s preferences, HW had instructed his wife to prepare a very simple lunch of salad, with nuts and apples placed about the room. HW relates some of their conversation in his book. There is no mention of motorcycles, but surely HW would have mentioned that he had owned a BRS Norton! Was the 1928 Morris on view – or hidden away in the garage? There is no photograph marking the occasion – HW would have been extremely sensitive to TEL’s antipathy to being photographed – nor are we told which particular Brough Superior it was of the many that TEL rode; but in 1929 it would have been SS100 ‘George VI’ motorcycle (UL 656). HW does tell us that he was in his habitual black leathers. He stayed about an hour, then it was time to return to duty in Plymouth.

|

|

A well-known photograph of TEL collecting ‘George VI’ from George Brough |

The two men met just once more, again briefly, in early 1934, as HW boarded the SS Berengaria for his second visit to America. Lawrence, then stationed at Southampton working on high-speed rescue boats for the RAF, came to see him off. On 13 May 1935, soon after he had left the RAF and was living at Cloud’s Hill, TEL met with the motorcycle accident (riding ‘George VII’, GW 2275) which caused his death a few days later. He had been returning from sending HW a telegram, inviting him to lunch on the following Tuesday. HW wrote the story of their friendship in Genius of Friendship, published in 1941.

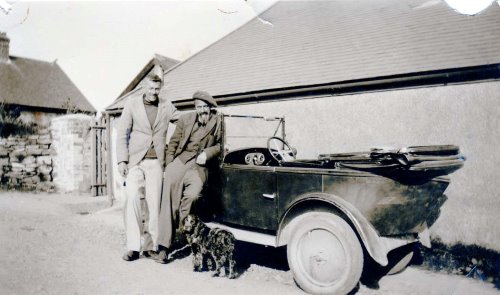

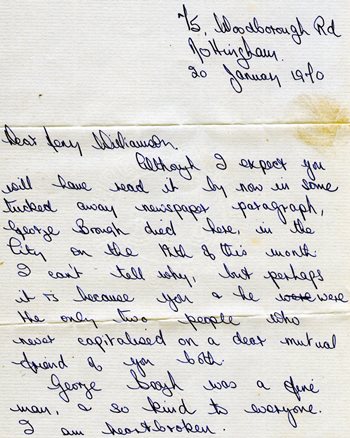

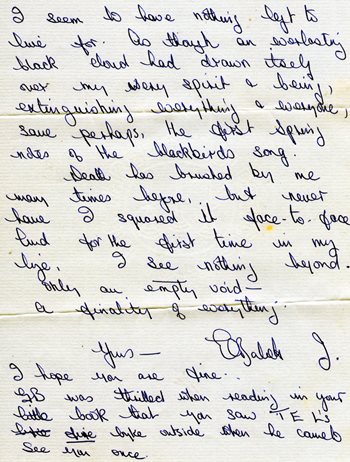

There is a moving postscript to this episode in HW’s life. It concerns the death of George Brough, as we find from the following poignant letter sent to HW from someone who was obviously a very close friend in Nottingham, dated 30 January 1970. Although it is very sad – and personal – I include it as it is a moving tribute to George Brough.

Transcript:

Dear Mr Williamson,

Although I expect you will have read it by now in some tucked away newspaper paragraph, George Brough died here, in the City on the 12th of this month. I can’t tell why, but perhaps it is because you and he were the only two people who never capitalised on a dear mutual friend of you both.

George Brough was a fine man, & so kind to everyone. I am heartbroken.

I seem to have nothing left to live for. As though an everlasting black cloud had drawn itself over my very spirit & being, extinguishing everything and everyone, save perhaps the first spring notes of the blackbird’s song.

Death has brushed by me many times before, but never have I squared it face-to-face. And for the first time in my life, I see nothing beyond. Only an empty void – a finality of everything.

Yours— Elizabeth J.

I hope you are fine.

GB was thrilled when reading in your little book that you saw TEL’s fine bike outside when he came to see you once.

There is no indication who this lady was, nor of her connection with HW; but she obviously knew and was very fond of George Brough, and knew and held HW in some esteem. There seems to be the inference that HW himself knew Brough – but I have found no evidence anywhere to confirm this. However, there are still many new things to learn about HW’s complex life!

When TEL made that visit in July 1929 plans were well in hand for the Williamson family’s move to Shallowford that Michaelmas. HW was now a well-established author, both here and in America. Indeed, his American publisher, John Macrae (of Dutton Publishing) invited HW to join him and his son and son-in-law on a fishing trip to Mastigouche, a fishing club on lakes in the Canadian outback north-east of Quebec. HW embarked on 6 September 1930. The visit is worth a short digression. At Mastigouche life was still almost in an earlier age. Their transport was by canoe and ‘portage’ as HW described in a letter home to his wife:

The canoes are lovely, 60 lbs, the guides carry these from lake to lake. Balance a careful business.

The first photograph shows HW with his French-Canadian guide, René, canoe, and fish catch. On the back of the second, showing the change-over of gear and luggage from a horse and cart to a car, HW wrote:

Where the waggon track ends, & car track begins, homeward journey 30 Sept. 1930.

(I have not been able to identify the make of that car!)

Fishing holiday over, HW returned with the Macraes to New York, where he settled down for a winter of writing in Greenwich Village. The outcome of this visit was The Gold Falcon, a book which basically describes, in considerable detail, the frenetic New York scene as it was in the 1930s, its cars and noisy trams and ‘speakeasies’; but it also has a mythical aspect, ending in the death of the hero, Manfred, in the Atlantic when the aeroplane in which he is flying home to his dying wife, a ‘blue and silver monoplane’ (a Lockheed-Beaumont Altair), ditches in the water where, in a scene of mythic drama, he drowns. HW checked the various ‘technical’ flying details with his wife’s cousin, Sir Francis Chichester (famous first as a round-the-world pioneer aviator and then in later years for his voyages as a solo sailor with his series of yachts all named Gipsy Moth, for which achievements he was knighted).

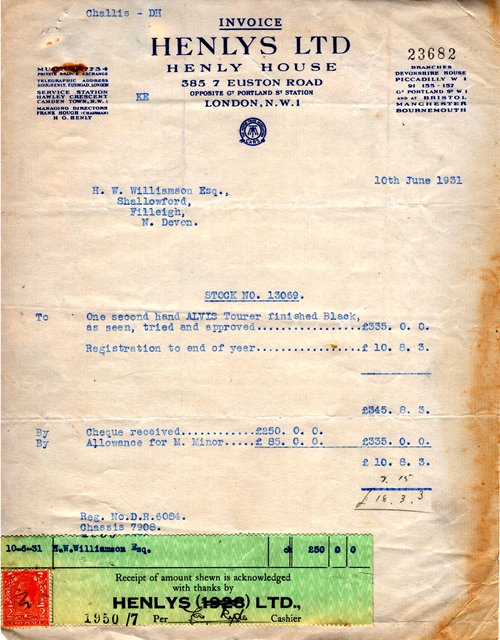

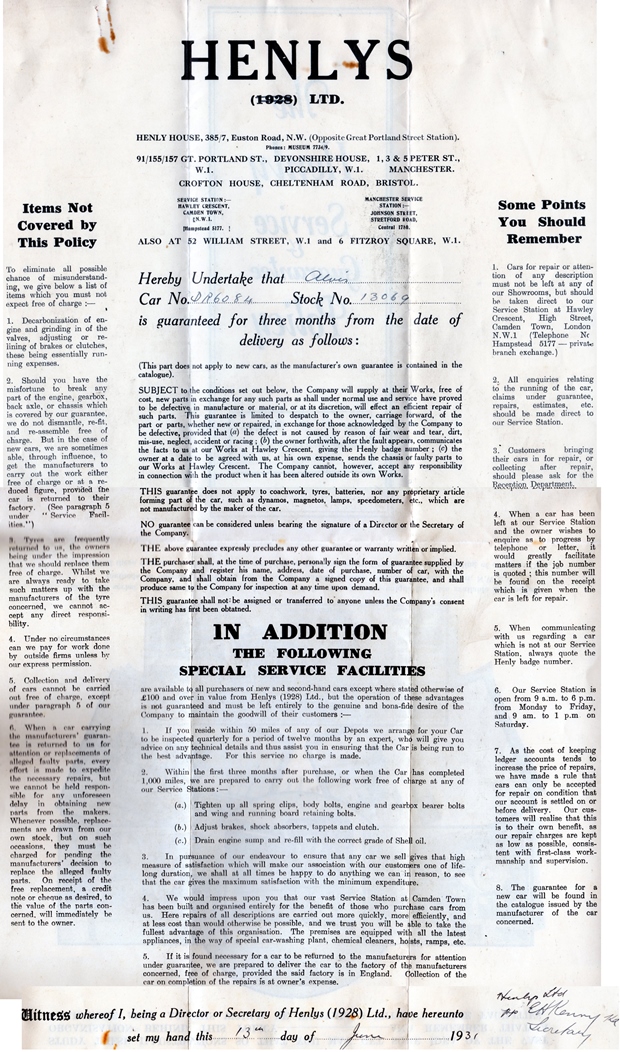

While in New York HW had written to his wife to say that on his return he intended to buy a fast car in order to facilitate business visits to London. He returned to England on 17 March 1931. On 10 June 1931 he bought from Henlys Ltd of London, as recorded on the Bill of Sale:

One second hand Alvis Tourer, finished black as seen, tried and approved, . . . £335.0.0

The document also notes: Registration no. DR 6084; Engine no. 8352; Chassis no. 7906. He was allowed £85 for the Morris in part exchange.

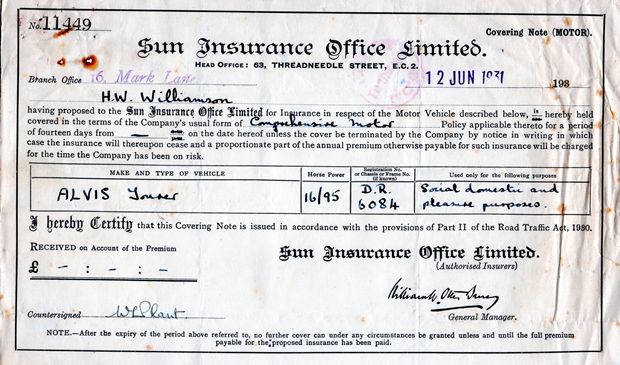

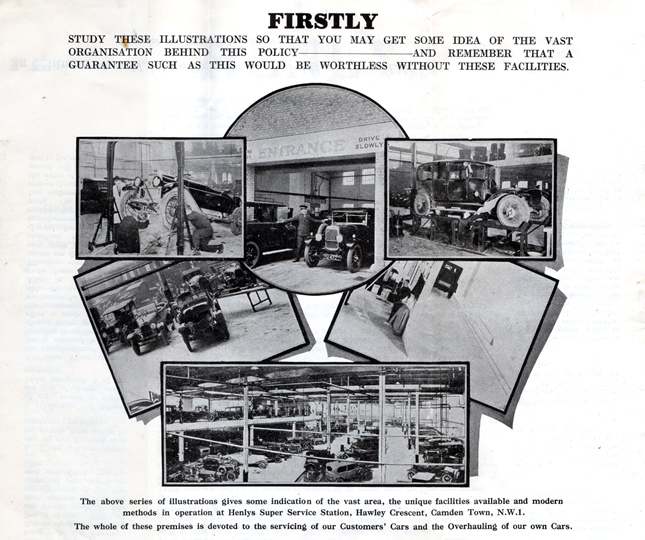

Subsequent documents from Henlys refer to a stock number, 13069. HW’s 14-day cover Sun Insurance certificate that accompanied the car notes the horse-power as 16/95. Particularly interesting is the most elaborate Service Policy, which, when unfolded, was so large that it had to be scanned in sections. As reproduced here the print is so small as to be well nigh illegible.

However, there is little to tell us how HW came to buy that particular car from that prestigious Automobile Car Agency. (Addresses for the various sections of the firm range from Devonshire House, Piccadilly; Great Portland St. W1; Fitzroy Square, W1; Henly House, Euston Road; a works and service station in Camden Town, and also premises in Manchester and Bristol.)

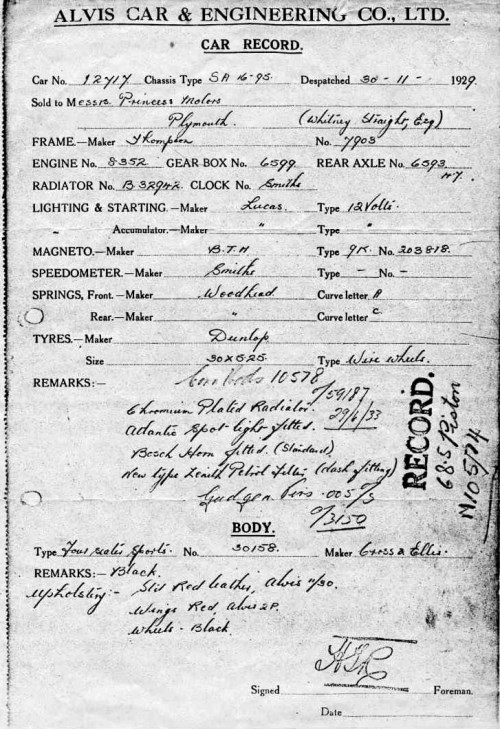

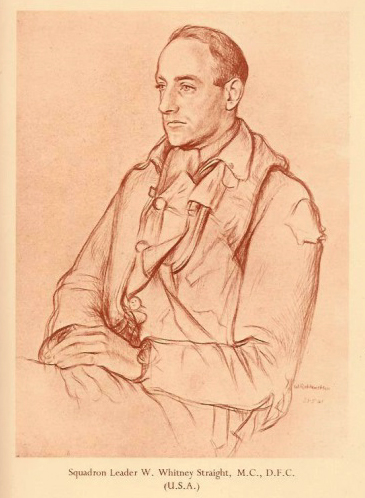

Neither is there anything within the correspondence documents that reveal that the previous owner of the car had been Whitney Straight, already then well-known in the hill-climbing world, although that information would have been in the car’s Log Book. Whitney Straight, born in the USA in November 1912, had been brought to England when his mother, an heiress, remarried Leonard Elmshurst after the death of her husband Major Straight in the 1918 influenza pandemic. The Elmshursts took on Dartington Hall in Devon, founding the famous progressive school, where Whitney was educated before going on to Cambridge. The 1930 Alvis ‘Tourer’ (a new Silver Eagle, cost £559) was Whitney Straight’s first car at the age of 17, apparently a birthday present (his birthday was 6 November). This is a copy of the original car record sheet from Alvis showing its delivery new to Whitney Straight in November 1929; interestingly it shows that it was delivered with red wings. During HW's ownership they were black, and in later years Loetitia recalled that he had them resprayed:

Straight was interested in competition driving from the start, and took part in hill-climbing events at Shelsley Walsh and Prescott – and Brooklands. He was obviously hard-wired to be a racing driver! From its condition a year later, he drove the Alvis hard and fast. In the summer of 1931, deeming the Alvis unsuitable for his purpose, he exchanged it for a Riley Nine, more appropriate for the hill-climbing events that he then went on to win. He soon moved on to actual racing, first in a Bugatti, then the famous black and silver Maserati (previously owned by Tim Birkin). Apart from his motoring fame, Whitney Straight had a very distinguished war in the RAF, flying Spitfires in the Battle of Britain with 601 Squadron. He was shot down in 1941, taken prisoner and escaped, and was awarded the MC and DFC. Straight finished the war as an Air Commodore. Post-war he would become managing director of BOAC and sit on the board of Rolls Royce, being made a CBE. He died in 1979.

|

|

A fine portrait sketch by Sir William Rothenstein (Men of the RAF, OUP, 1942). |

Dartington Hall is not far from HW’s home at Shallowford, and I had assumed that HW heard locally that the car was for sale and rushed off to London, no doubt telephoning his interest in advance, to make his purchase. However, I have now deciphered a faint duplicate letter from the County Garage, Barnstaple, to Alvis Cars (see later for reasons underlying this) stating that they had recommended that HW bought an Alvis, and had hoped to sell him a new one, but that he had been to London and ‘purchased this one. Undoubtedly he has been unfortunate with it.’ I would still assume that the local connection was a factor in his choice.

A letter to HW, dated 10 June 1931, from Henlys sales director, G. Challis, reveals HW had very sensibly had an AA report done on the car, which had revealed several problems, including that the radiator was to be ‘exchanged’. In the letter Challis also thanks HW for his ‘kindness in leaving a signed copy of “The Old Stag”. I do very much appreciate that kind of book.’

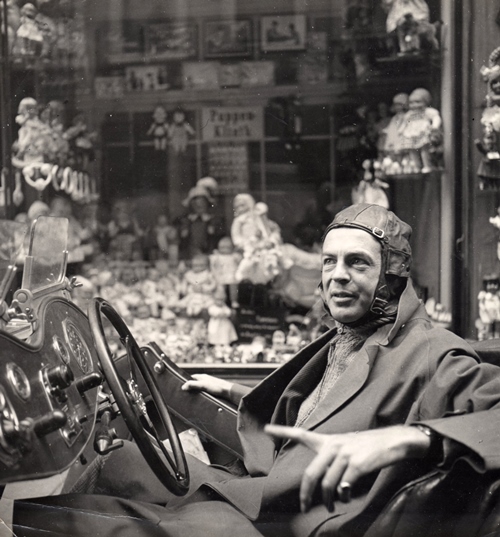

The car was to be delivered to HW on ‘Saturday next’, rendezvous to be outside Salisbury Station at 1 o’clock. (Salisbury being conveniently halfway between London and Devon.) Another receipt shows HW had had fitted ‘a spot lamp’ (£2/10/0) and a ‘radiator stone guard’ (£5/0/0). Meanwhile HW had equipped himself with leather flying helmet and coat, goggles and gauntlets – ready for flying along the Devon lanes.

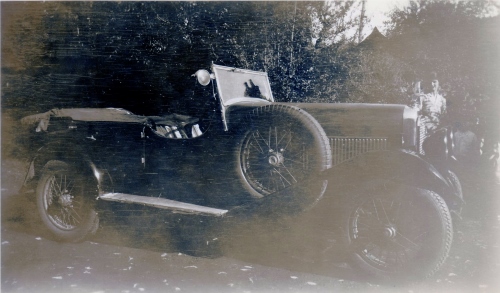

|

| An early photograph, somewhat faded, of the Silver Eagle |

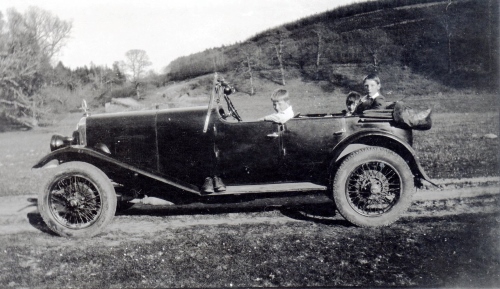

|

|

Another early photograph, with village children on board, probably taken in the Deer Park at Shallowford. Why there is a pair of shoes on the running board is not known! |

HW wrote of the purchase of his Silver Eagle in his novel The Phoenix Generation (1965, vol.12 of A Chronicle of Ancient Sunlight) in which Phillip Maddison is based closely – though sometimes loosely – on HW. The fictional time is May 1929 and Phillip has bought

a Silver Eagle, a six-cylinder, three carburettor sports car . . .

Phillip’s friend Piers Tofield (based on HW’s close friend John Heygate, who owned an MG Magnette at that time)

thought his friend had paid far too much for the second-hand car. It was less than a year old but the exhaust smoked blue, the engine used a gallon of oil every one hundred miles. Obviously the previous owner had caned it. . . .

(A rare error from HW there of course: a Silver Eagle bought in May 1929 could hardly have been second-hand!)

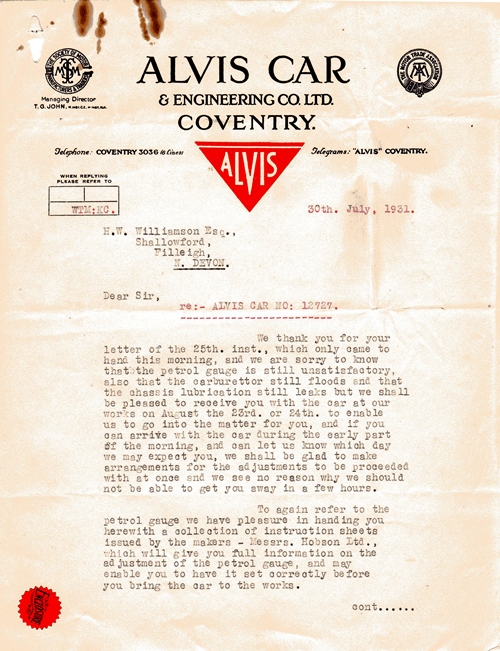

In real life, in 1931 there was a further ping-pong exchange of letters, first from Henlys, but very soon also the Alvis Car Company, and involving too the County Garage in Barnstaple (who were evidently agents for Alvis Cars), which reveal a series of problems, an increasingly irritated HW, and extremely polite and patient – but obviously bewildered – recipients trying to solve problems which they thought did not exist but HW insisted did!

This letter, dated 30 May, gives the car as being Alvis stock number as 12727 --- but this seems to be an error as all subsequent letters refer to car 12717. It begins:

. . . and goes on to insist that all were checked and correct both at Henlys and at the Alvis works.

A letter from Henlys, dated 22 June 1931, reveals that the car had been returned to them, as they are doing fairly major work on the cylinders: they have removed scoring from No 1 cylinder by ‘grinding out the bores to 69.5 mm’ (an error corrected in their next letter to ‘68.5 mm against the standard measurement of 67.5 mm’) and are ‘awaiting the oversize pistons from Messrs Alvis’. Another letter implies that the Silver Eagle had actually been into the Alvis Works in July, as their bill becomes a bone of contention. The carburettors were a major problem. Alvis sent a list of instructions (sadly not present in HW’s archive), but it is rather obvious that HW had already tried to solve the problem in his own way, thus exacerbating the situation. The letter explains that a particular nut (evidently the one HW had played with!) had nothing to do with the calibration – and (in my understanding of the technicalities here) that if the central carburettor was tuned correctly the others would be automatically aligned.

But despite all these ongoing problems, in early September 1931, three months after its purchase, HW and his wife set off in the Alvis for a holiday on the Isle of Islay in Scotland at the invitation of Gipsy’s cousin, Sir Stephen Renshaw and family. HW included a chapter on this fishing holiday in his book A Clear Water Stream (1958), which opens with basic details about the car: ‘six cylinders, 3 carburettors, up to 4800 rpm, 80 miles an hour – the driver wears leather coat, goggles, and flying helmet’.

The particular point of interest here is that on his way north HW stopped off at the Alvis works in Coventry on 6 September, recording that it was ‘to have the timing checked and the carburettors synchronised’. At the end of this chapter HW notes that he did the return journey all in one go – 550 miles: so around 1,100 miles all told – and with no further problems mentioned.

|

|

A pair of photos showing HW and Ann Thomas taking turns at the wheel, perhaps taken near Tenterden, Kent, where Ann lived |

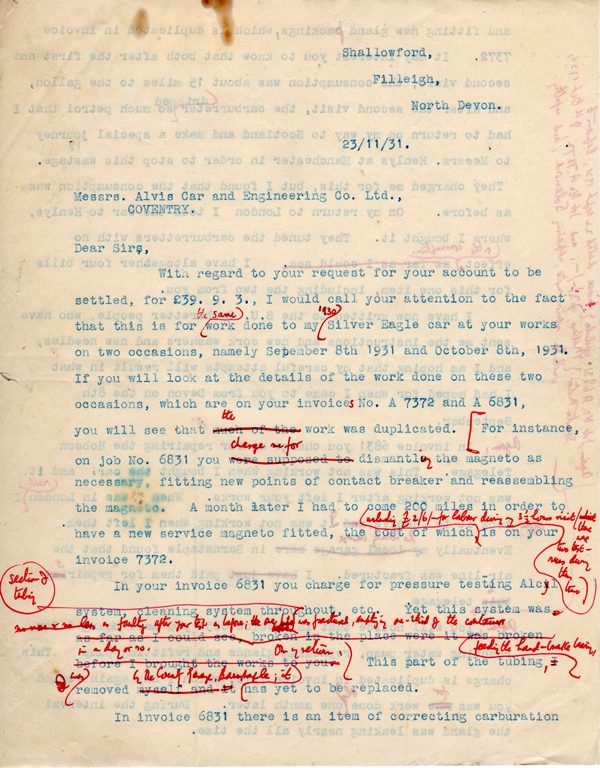

On 19 November Alvis Cars wrote to ask for payment of their overdue invoice of £39.9s.3d. for work done in July and September, but HW disputed the amount, stating that some items were duplicated. Alvis refuted this and itemised the work carried out. The sum included labour charge – ‘4 mechanics and a tester were involved on your car on the last occasion it was here’ – the cost for five people over no doubt several hours being £2.6s.0d., almost ludicrous by today’s prices. Other items attended to include the Alcyl lubricating system, the Hobson petrol gauge, and water pump glands.

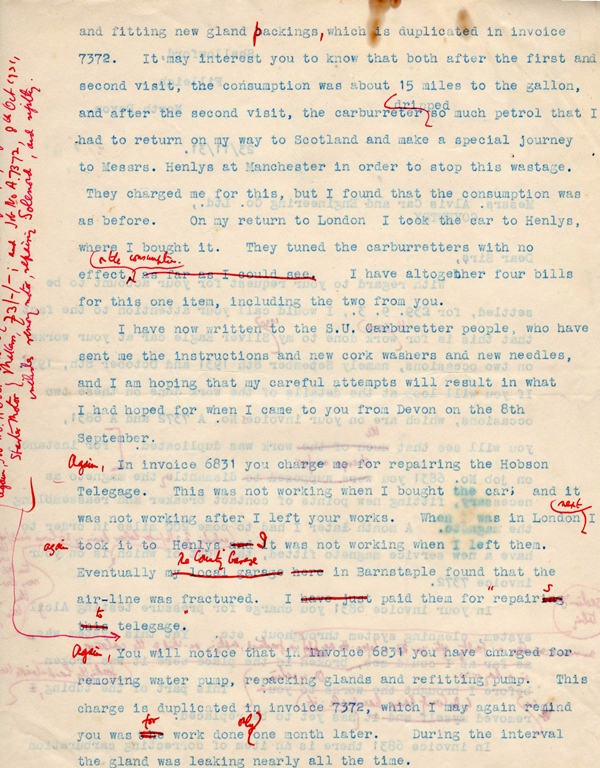

There are three copies of HW’s lengthy letter of complaint, which show his usual agitation in dealing with such matters. But the very formal reply from Alvis is almost as ‘wordy’. HW’s reply to that (there are at least three drafts) covers several typed quarto pages; this is one of the drafts:

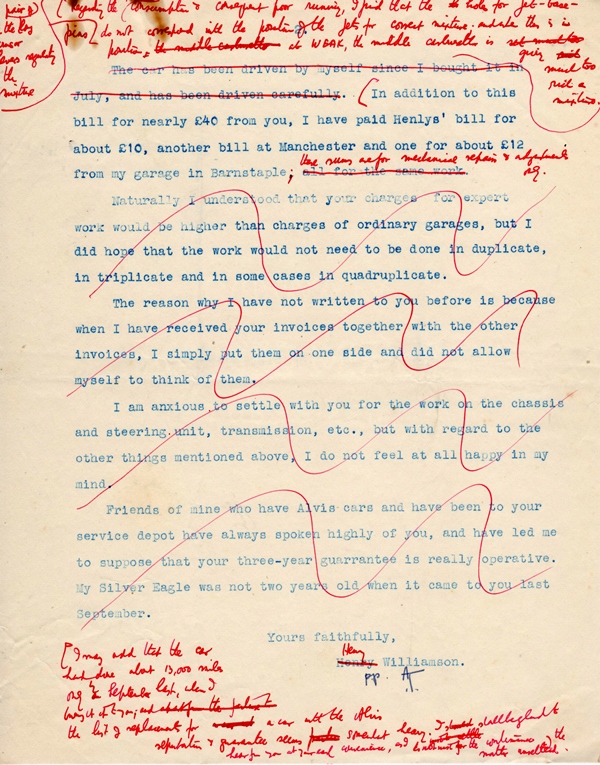

Then The County Garage at Barnstaple also became involved:

To show good will (and no doubt to end the dispute) Alvis gave HW a generous discount – and the matter was settled.

Further letters show work carried out in November 1933, and in 1934. The radiator problem seems to have finally been resolved by Messrs Sercks Radiators in the summer of 1935 offering to fit a new

filter type centre, which we have proved is far less subject to “weeping” than the old type round-tube honeycomb.

Despite all the problems the Alvis was in constant use, and HW covered a huge number of miles, back and forth to London for business purposes, and for visiting friends, particularly his secretary/mistress Ann Thomas (daughter of the writer and poet Edward Thomas, killed in the First World War).

*************************

Here we make a diversion, or to use a motor racing term – a chicane. In the early autumn of 1935 HW made a visit to Germany at the invitation of his closest friend John Heygate (who appears as Piers Tofield in the Chronicle series), who was then working at the UFA Film Studio in Berlin. At that time HW was in a state of extreme exhaustion and the thought of a holiday was a godsend – all expenses paid, as he thought, by Heygate as a thank-you for help given, but much more probably financed by the Germans as a good propaganda exercise.

It had been a very difficult year for HW, emotionally and workwise. His once school-friend Victor Yeates had died of TB, having just managed, with HW’s help and under dire circumstances, to finish his renowned book Winged Victory (the fictionalised story of his time as a pilot in the last year of the Great War). HW made himself responsible for promoting Yeates’ novel on behalf of his impecunious widow and young children. This involved considerable difficulty, time and energy. Then in May T. E. Lawrence had died after his motorcycle accident. It is obvious HW felt responsible, in that TEL would not have died if he had not been on that road at that moment, returning from sending HW a telegram inviting him to lunch the next day.

At that point HW virtually locked himself away in his Writing Hut in the Field above Georgeham in order to complete his book Salar the Salmon – now overdue, as publication was fixed for the autumn. It was not an easy book to write, needing intense concentration to reproduce the underwater world of a salmon as an interesting story. That he pulled it off is a feat of his power as a writer. Just as he finished the book his fifth child, Richard, was born on 1 August 1935, meaning the household was thrown into ‘baby chaos’ once again. His need to escape was paramount!

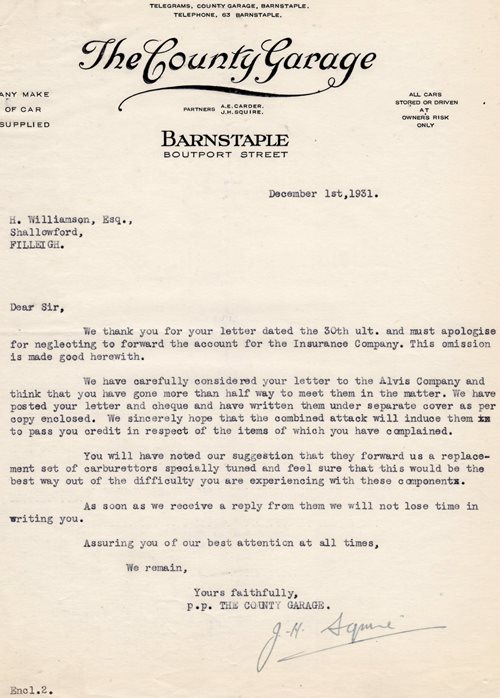

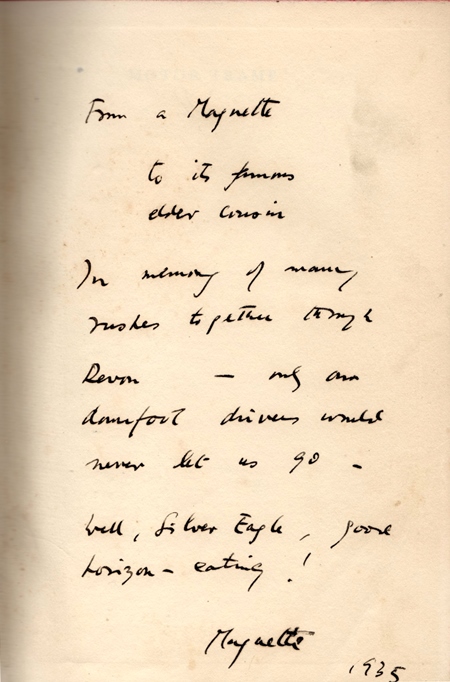

John Heygate (1903–1976), who had worked previously for the BBC and Gaumont Films, was also an author: HW had been instrumental in getting his first book, Decent Fellows (1930), published. Heygate had a great enthusiasm for Germany, having been educated at Eton and then Heidelberg University. He was also a motoring enthusiast, and was then driving an MG Magnette. He wrote up his considerable adventures with this car in Motor Tramp (Jonathan Cape, published early 1935). He gave HW a copy of this book inscribed as if from his MG to the Silver Eagle:

Although Heygate describes collecting his car (from ‘Abingdon’) and writes about it in detailed affection, he never once mentions the make or model as such. I am presuming he thought afficionados would have known, and that it wouldn’t have mattered to a general reader!

In a long quiet hall the new cars were echeloned up, awaiting owners. There must have been thirty or forty, all of them four-seater open models with their hoods up, black with red upholstery, and the flat caps of their radiators made a straight silver line down the hall. A tester in brown overalls jumped into a car and drove it from the line. The sharp high note of the new engine beat against the roof. . . . I drove it in third gear from the works, down Abingdon High Street . . .

It was a long narrow deep-lying car, underslung front and rear so that it looked built up from the ground it stood on; a cat could just about crawl in underneath without singeing its fur on the exhaust piping. It was a small car, built down from a model that had won fame on the race track.

And a few pages further on, already in Germany and in a conversation with a keen young lad, we discover that his car had ‘six cylinders, two carburettors, twelve horses, 1270 c.c. – did 110 to 120 kilometres an hour, had four gears and reverse'.

However, the car Heygate describes in Motor Tramp was not the same car as the one he was currently driving in Germany, as can be seen by comparing the number plates in his photograph and that of HW in his own write-up of this German holiday in Goodbye West Country (1937): the former being CG 1425, the latter CG 9230. At the end of Motor Tramp, Heygate, having driven the car hard and fast all over Europe, including the Alps in winter, writes of returning in it to the Abingdon works – apparently merely to have the car serviced, driving off in it again after a few hours. I rather suspect that the car he actually drove off in was a new one – the one that in 1935 he was driving HW around Germany. There are two photographs taken by HW of the MG Magnette in Germany, near a level crossing; the first is reproduced in Goodbye West Country:

John Heygate is the driver in the first photograph and the figure standing in the second. The person in a white helmet, seated in the rear, is Chemitzer, the ‘guide’ (or minder) assigned to HW from the beginning of his visit to Germany. HW referred to him in Goodbye West Country as ‘K’ (the German ‘ch’ is hard – ‘K’). K’s job was to escort HW, to guard and to guide, to make sure that he saw what officialdom wanted him to see, and heard what officialdom wanted him to hear. K was good at his job, and HW was fed the very convincing official line and, wanting to believe in the good of Germany and its leader, was very impressed by everything he saw: the new autobahns, the cleanliness, the emphasis on agriculture, and the activities of the German Youth Movement.

|

| John Heygate, somewhere in Germany |

However, the main point of this diversionary chicane is the exciting event that HW briefly describes in in what is almost a ‘throw-away’ few lines.

Southwards again, the low small car cornering effortlessly. And then, suddenly, we came upon an inn with two white cars in front, mechanics knocking on wheels as at a race-pit. We stopped, examined, admired. They were Auto-Unions, just back from the Dolomite races. With a wave of hands we went on, and were cruising down a straight bit of road about 70, five minutes later, when I thought our engine had blown up or the chassis had fractured: such a clattering, iron-vibrating sound. I had the Rolleiflex camera open at the time, with the 1/300” speed, to take a low photograph of the rushing road. At the clatter I looked up: a white flash passed us, the clattering of open exhaust with it. Von Stuck in his Auto-Union was a quarter mile in front. I’d clicked shutter involuntarily, and now hurriedly cranked up another square of film; too late, he was gone, showing the Englanders where their M.G. stopped. Those Auto-Unions do 200 m.p.h.

That was September 1935: and it was not just one of the cars but Hans Stuck himself at the wheel, one of the great names of the motor-racing world, driving at that time the Type B, with a V16 4.9 litre engine, producing 375 bhp at 4000 rpm.

HW took the opportunity of photographing these futuristic-looking rear-engined racing cars; only one of this unique series has ever been previously published (in Goodbye West Country):

|

| The Auto Union overtaking Heygate's MG Magnette |

No Auto Union had been seen in England at that point, although no doubt the newspapers and motoring magazines of the time would have been full of information about this exciting revolutionary new car. Designed by Professor Porsche, the car had only come into being the previous year after Hitler, newly Chancellor of Germany, had decreed a large amount of money to be spent on developing a car that would win Grand Prix races – and so enormous prestige – for Germany. Hitler pitted this car against the previously top German car, and rival firm, Mercedes-Benz (from Daimler-Mercedes). Together the two marques became known as the ‘Silver Arrows’.

The two main Auto Union drivers for 1935 were Hans Stuck and Prinz du Leinengen. Stuck (1900–1978) was better known for his hill-climb successes (for which he took the title ‘Mountain Champion’), but in 1934 his fame was with the Auto Union and the Grand Prix races in Europe, winning the German, Swiss and Czechoslovakian races, and coming in second in the Italian.

In Goodbye West Country HW refers to Stuck as ‘just back from the Dolomite races’. HW had left England en route for Berlin on 6 September. On 8 September Hans Stuck, driving an Auto Union, won the Italian Grand Prix at Monza, and the up-and-coming young driver Bernd Rosemeyer (having taken over another Auto Union when his own broke its back axle) came third. Second was Tazio Nuvolari (who also took over another’s car, and also got fastest lap) in a Ferrari. As HW arrived in Berlin the newspapers must have been full of the success of the Auto Union and its drivers. To have then actually seen the two cars must have been very thrilling indeed.

The following year, in June 1936, a slightly further improved Auto Union was seen in England for the first time at Shelsley Walsh, ‘England’s International Speed Hill-climb’. The event is described, with considerable writing skill, in C. A. N. May’s Shelsley Walsh (1946):

Early on Friday June 5th 1936 a big box van, obviously foreign and bearing strange number plates, drew into Shelsley’s orchard-paddock; burly mechanics opened the rear doors, a ramp was let down, and out onto the grass came a strange, powerful-looking, silver-grey racing-car. It was one of the most talked-of cars of the day, the 5½ litre, rear-engined German Auto-Union racer, and its presence at Shelsley Walsh meant that Stuck had come back to the hill.

Immaculately clad in grey driving kit, Stuck put in several practice runs and was unofficially clocked at 40 seconds. [He said that] the car had “far too many horse-powers” for a short, sinuous climb like Shelsley, and that it was really too long, although the chassis was 20cm shorter than the full Grand Prix model.

In October 1937 Auto Unions appeared at the British Grand Prix at Donnington. The race was won by Bernd Rosemeyer; and in 1938 it was won by Tazio Nuvolari, now driving for Auto Union. Rosemayer was killed in 1938 in an attempt (on an ordinary autobahn) on the land speed record, when he lost control of his Auto Union and crashed. The 1939 race was cancelled – for by then the Second World War had broken out.

*************************

The chicane over, we now return to the main track: when HW returned to England at the end of his 1935 holiday it is obvious he was perturbed. He had been shown the best of Germany and its modern wonders – autobahns, cars, aeroplanes – but it is plain that although he was convinced that Hitler (an ex-Great War soldier like himself) would never go to war, he could also see that the political situation was not stable and that another war was quite likely on the horizon. His experience of the Great War, with the death of the cream of European youth, had given him a horror of another war. His personal solution to the dilemma he found himself in was his decision, at the beginning of 1936, to take up farming, on the advice of his friend, publisher, and earlier best man, Richard de la Mare (son of the author and poet Walter de la Mare). In that way he could both support his country and keep his family safe, without being involved in the war itself. And so he began the lengthy process of buying a farm in north Norfolk. Explaining how this decision came about, his book The Story of a Norfolk Farm opens:

One dull day in 1935 [it was after Christmas, and over the New Year] I went to London in my open car which I loved. It was painted black, and all the seats were covered except the driver’s, in which I sat as in the cockpit of an airplane. There was a sense of freedom in my car, which had a silver eagle as a mascot on the radiator cap. It was fast, doing 85 m.p.h. when flat out, and it covered 24 miles to the gallon.

No mention of any problems with it! De la Mare invited HW to spend the New Year with them in North Norfolk, and during that time the decision to buy nearby Old Hall Farm in Stiffkey was made. HW returned to Devon to inform his wife and family.

At the end of January HW made a further visit to the Norfolk Farm, together with Ann Thomas. The pair then continued on to the Lake District as HW had decided to write a story about a fox (see Fergaunt the Fox) and needed to get some local ‘colour’ and facts about the foxhunts in that area. They returned to Devon on 10 February. That meant hundreds of miles being clocked up in that one journey alone. Some unmarked photographs would appear to belong to that visit – note the hood is still down, despite the cold weather and snow on the ground!

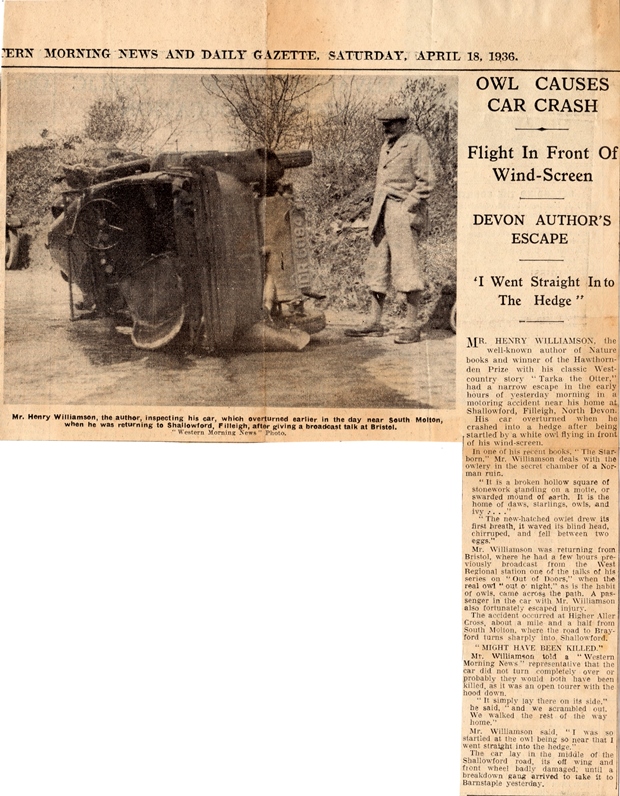

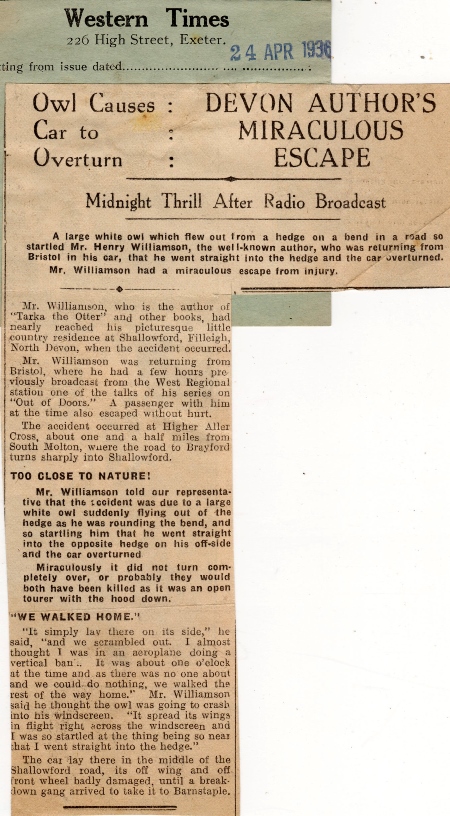

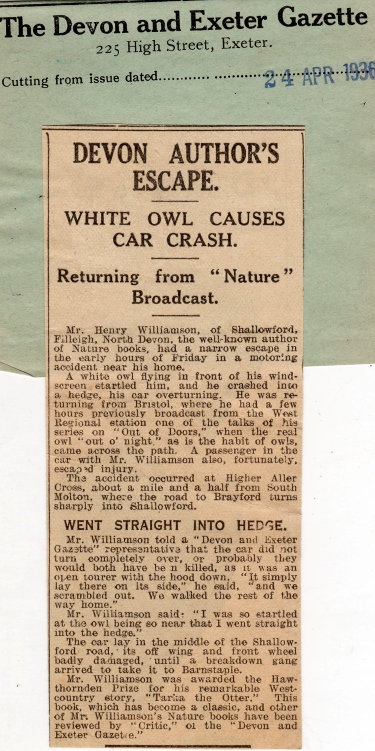

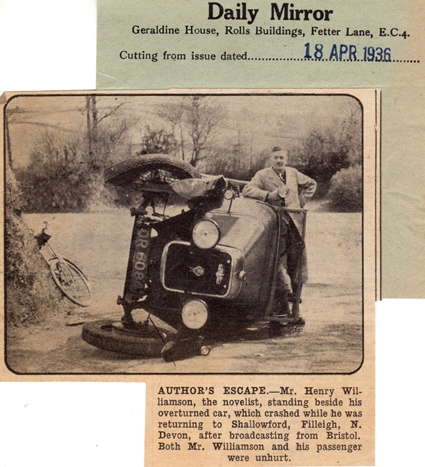

During this period HW was giving radio talks, broadcast from the BBC Studios in Bristol; he either drove there or travelled by rail. On 16 April 1936, driving home after one such talk, late at night and tired, he overturned the Silver Eagle when a white (or barn) owl flew across his windscreen as he turned a corner when nearly home. The next morning the opportunity for photographs was to good to miss:

The incident is described in Goodbye West Country (1937) in the entry for 17 April, which ends:

I watched the poor old Eagle towed away, twisted front wheels and bent axle up in the air. It will be repaired.

Note that it is the County Garage in Barnstaple dealing with the incident. The accident was reported in the local and even national press:

While the Alvis was hors de combat, HW used what he refers to in the book as a ‘very ancient Crossley’ left with him by his wife’s brothers when they emigrated to Australia.

|

| The Williamson children in the ancient Crossley . . . |

|

|

. . . and in John Heygate's MG Magnette. On the back seat is Windles, his friend 'Sleeboy', unknown, and John. In the front is Margaret. |

The documents for the purchase of Old Hall Farm were finally signed on 22 August 1936. HW immediately set off with his wife and eldest son for a ‘camping holiday’, as he describes in The Story of a Norfolk Farm:

We left in the Silver Eagle, Loetitia beside me and Windles in the back, wearing my goggles and helmet, the tent, provision basket, water jug and kettle beside him. . . .

We drove slowly along the top lane to the farm, through an ancient gate, and so to the pines on the Castle Hills.

|

| Windles and Loetitia at the camp in the pine trees |

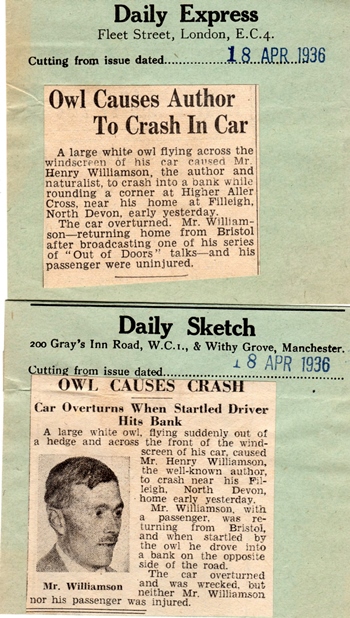

Legally HW would take over the farm at Michaelmas 1937, but it was decided that the family would not move until accommodation and other details had been sorted out. In the early summer of 1937 HW, together with his brother-in-law, ‘Bin’ Hibbert, whose help had been enlisted and had returned from Australia to do so, decided to go to Norfolk and camp on the farm in order to begin some of the work involved prior to the official hand-over. To facilitate this HW ‘acquired’ a trailer for the Alvis: we read in A Solitary War, the Chronicle novel which covers the early farm years, that the trailer was made from what was left of the old Crossley. He also obtained a Morris Commercial lorry:

Bought a reconditioned 1932 Morris 2-tonner from Moor of S. Molton today for £66.10.0d. Tipper, hoops and hood, engine, all new – rest made 100%. We have a 2-ton trailer (£21), this lorry, a £9 trailer, & caravan for our summer road-building campaign.

|

|

Alvis and trailer in the Field at Ox’s Cross, standing in the trailer is Windles (HW's eldest son Bill, then aged 10) |

Everything was very fraught, with HW in the highest of nervous states, but in due course the vehicles were loaded up with the various immediate necessities, and what HW called ‘the Flying Column’ set off for a long, complicated and difficult journey to Norfolk.

At 2.30 p.m. on Friday, 21st May 1937 our column left for Norfolk. First went the Silver Eagle, drawing an old pattern of caravan, fitted with two beds, wash-bowl, shelves, tables, oil-cooking stove and cupboard. Loaded it weighed about a ton. Behind came Sam, driving the green lorry, to which was attached the trailer, on which lay the dinghy covered by a green cloth. The lorry also had a new green hood, supported by three ash loops. . . .

Soon we came to the dark silhouette of a group of buildings which turned out to be a gravel-washing and sifting plant. There was a concrete semi-circular entry and exit from and to the main road. It was an ideal parking place. We pulled in, made the beds in the caravan and lay down to sleep.

|

|

|

The Flying Column, front and back views, halted at the gravel-washing plant. The bearded 'Bin' Hibbert ('Sam' in The Story of a Norfolk Farm) is standing next to the lorry. |

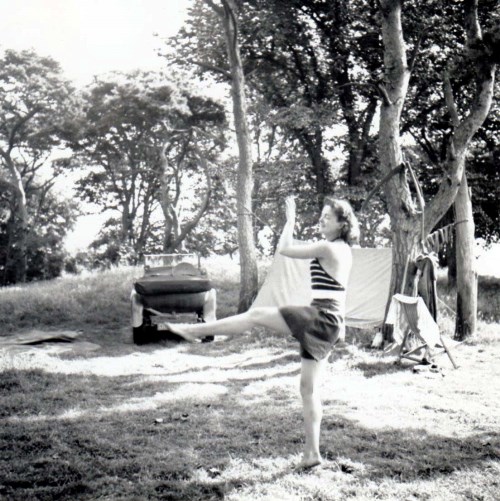

On arrival at Stiffkey they set up camp under pine trees above the farm, always referred to as ‘Pine Tree Camp’. The two men immediately began the backbreaking work of road-building. This involved endless trailer-loads of gravel from the quarry, topped off with chalk. This is all described in detail in chapter 15 of The Story of a Norfolk Farm, and again in the later Chronicle volumes. Ann Thomas arrived to look after the men, and carry out her secretarial duties, as always very efficient.

|

|

Ann Thomas at her callisthenics, Pine Tree Camp. She developed mumps shortly after this and had to go into isolation in her tent. Meals were passed to her through the front flap. |

Once the farm was officially his, the Alvis was enlisted into actual farm work, despite the fact that HW very early on bought a Ferguson tractor – ‘the little grey donkey’; it arrived 10 December 1937. This was the early Model A. (Later on he also had a Ford Ferguson model.) HW was writing and broadcasting articles on his reclamation of the farm and his farming methods at that time. These came to the notice of Harry Ferguson himself, and there is a small number of letters about farming and Ferguson’s own plans to improve agriculture in HW’s archive.

HW describes the arrival of the little grey donkey in The Story of a Norfolk Farm (chapter 25, ‘The First Furrow’):

The Ferguson tractor . . . was half the weight of an ordinary tractor, built of aluminium and immensely strong steel, and it carried its twin furrowed plough under its tail, on three steel arms that looked like a grasshopper’s hind legs. . . . It had a petrol engine which looked absurdly small . . .

On 6 December he recorded sending a cheque:

For Ferguson, including plough, cultivator & power pulley £282/10/- less 10%: . . . £252

And on 18 December a further

. . . £47 less 10% for rubber wheels. They are giving me £5.5.- rear mudguards for free. So I get £334/15/- tractor for £296/10/-.

|

|

HW ploughing on the Ferguson (photo: John Fursdon) |

The Alvis was used for such tasks as pulling the harrow, transporting bulk seed and other small farming jobs – HW’s wife Loetitia bravely took in it a pig to be sold at market in nearby Fakenham. We read towards the end of The Story of a Norfolk Farm that a severe storm flooded the farm meadows and tore off the hood as HW drove round the farm trying to deal with stranded animals.

At the very end of the book (apart from an updating ‘Epigraph’) we read of a return ‘to the West’ for a much-needed break. The journey (in August 1938) in the Alvis Silver Eagle reveals HW’s great love for his car.

Most of the way I sat in the bucket-seat without a coat . . . the engine bounded forward at a steady sixty. Ten years ago (over one hundred and fifty thousand miles) the all-British car left the Coventry factory, but I could not part with it. It was part of my life, and had a soul, which is a sense of continuity. If we were destined to die together, let it be now; so open the throttle and hear once again the roar of wind in the ears. Seventy . . . seventy-four . . . and the needle quivered there. Oil pressure only 10 lbs., those big ends and journals were worn oval, and the oil spurted through them fast.

Once the war broke out petrol was severely rationed, and the Silver Eagle became a thirsty luxury. On 18 May 1942 HW’s diary records (it contains the barest of facts in between farming notes): ‘I bought a 1938 Ford car, never used more than six months, for £145.’ And on 17 July he noted that he loaded up the ‘little Ford with food and petrol & set off for Devon’ (he was escaping to his Writing Hut in the Field at Ox’s Cross).

We read in the Chronicle novels that the Silver Eagle became very dilapidated and extremely difficult to start. The engine had to be re-bored locally – as the Alvis Works in Coventry had been blitzed in the Coventry raids. At some point this thoroughbred Silver Eagle was made into a work-horse when Mr Ebbage, a carpenter in Stiffkey village, turned it into a farm waggon with a pick-up body: that is, the back seats and bodywork were removed and a box put in their place with a let-down back section for ease of loading. Unfortunately there are no photographs of the Silver Eagle in its new guise.

Life on the Norfolk farm continued throughout the years of the Second World War. It all took a great toll on HW and family life. As the war ended so HW sold the farm and, with a divorce already decided, they all moved to Botesdale on the Suffolk/Norfolk border near Diss, prior to HW’s return to live alone in Devon.

The Williamson family left the Norfolk Farm at the end of October 1945, and established itself in the capacious Bank House in Botesdale, near Diss, on the Norfolk/Suffolk border – the cars in hand being the heavily used and now mangled Silver Eagle and the 1938 Ford 8. For HW this was an interlude prior to his departure alone to Devon. He was busy with various writing projects, mainly the allegorical story The Phasian Bird, about a Reeve’s pheasant and set on a lightly fictionalised version of the Norfolk Farm.

In March 1946, while on a visit to London, he accidentally met up with the father of Ann Edmonds, a former ‘Barleybright’ girlfriend of the early 1930s, and so renewed acquaintance with her. Ann was now married with two young children. Always flying crazy, she had served as an ATA pilot in the war, delivering Spitfires and other aeroplanes to front-line squadrons, and at the time was running a gliding club at Redhill. HW recorded that in October 1946 –

I gave her the old Silver Eagle and she came up [to Botesdale] and on Wednesday we took it and the Ford to Redhill, Surrey.

Another document reveals that the Ford 8 was actually picked up at Ipswich on 12 October, where it had been reconditioned. HW continued down to Devon (in the Ford) to begin his new life. Ann used the Silver Eagle mainly to retrieve the tow ropes: gliders would be towed up by winch and then release the tow, which fell to the ground – the box-body no doubt being a handy receptacle.

The Silver Eagle features strongly in the last three volumes of the Chronicle, more or less as in real life, except for the final volume, The Gale of the World, which is set post-Second World War, when HW actually no longer owned the Alvis; but Phillip Maddison, his fictional alter ego, still does.

At the end of this novel the car ends its days when it is struck by lightning on the Chains of Exmoor in the storm that gave rise to the Lynmouth flood (described in superb vivid and detailed prose), and bursts into flames: a very dramatic ending for a faithful friend! Phillip, feeling an utter failure for various reasons, had driven to the Chains with the car loaded with faggots of wood and cans of petrol and had planned to set fire to this and immolate himself in the flames – thus ending everything. But in recovering from a lightning strike which kills his dog (thus saving his own life) he becomes a changed man and is finally free to begin his life’s work – writing the series of books he has planned for many years – in real life, of course, A Chronicle of Ancient Sunlight:

And getting to his feet, he ambled on, holding the dead dog to him as though a sleeping child was being carried, and coming to the Silver Eagle, a shimmer of blue, laid its body on the near-side seat. He was feeling [for matches] in the flapped pocket beside the gear-handle when there was a shriving flash; the motor-car became bleak, shorn of its shimmer. It fumed sulkily amidst a stench of burning rubber. A smoky yellow flame lit the side of the box body. Then other flames arose crackling; the faggots were on fire above the petrol tank.

Remembering the petrol cans, Phillip hastened away. He stood distant by a score of yards, watching while flames rose higher and higher until, with a sudden roar, the tank blew up, inducing a greater roar of expanding flames as the cans exploded and burning petrol spread to water plashes all around the motorcar.

(The ‘shimmer of blue’ is St Elmo’s fire – a well-known phenomenon of electric storms.)

In real life, after its use in the gliding world the car then went through several owners. Soon after HW’s death Richard and I received a letter from a Mr Pearce, giving the registration number of the Silver Eagle and wanting confirmation that it had been owned by HW:

This was a car purchased by my father from the Surrey Gliding Club at Redhill, and was being used for towing gliders into the air.

(The latter statement is incorrect: according to Ann Welch herself it was merely used for retrieving tow ropes.)

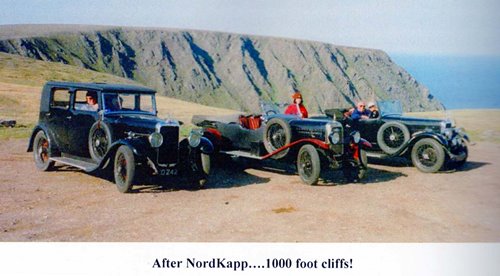

The car was eventually rescued by Alex Marsh, the current owner, who returned it to its original coach-work body and red wings, refurbishing the car to a high standard. The Silver Eagle has had many adventures in recent years. It has taken part in several long-distance rallies, one being to the south of France, another to the Arctic Circle.

|

| At Le Mans, 2007 |

|

| The Arctic Circle, 1999 |

In May 1994 the Silver Eagle returned to the Norfolk Farm, gracing a meeting of the Henry Williamson Society, where it was much admired. The photo shows HW’s first wife, Gipsy (Ida Loetitia Williamson), then in her 90s, sitting in the driver’s seat with HW’s son Richard and Alex Marsh looking on. She remarked that she thought she could still drive it!

Other photographs of the Alvis on this memorable occasion, together with some later ones, can be viewed on a separate page.

In October 1995 Alex took the car down to Devon for a meeting of the Henry Williamson Society. Here it is outside the cottage in Georgeham where HW first lived in the 1920s – a wet weekend, this is one of the few photographs of the Silver Eagle with its hood up!

Alex and Elspeth Marsh have written a very full history of the Silver Eagle during their long ownership, which was published in HWSJ 58, September 2022, pp. 10–35. This is also online, as an appendix to this page: 'Adventures with Alvis Silver Eagle DR6084'.

*************************

Go to:

LAP 2: Two wheels plus an engine (Nortons)

LAP 4: Moving up a gear (Aston Martin to MG Magnette)

Appendices: Tale of a Two Litre; and Aston Martin Statement

LAP 5: The car that never was (Bédélia)

*************************