YOUNG PHILLIP MADDISON

(Volume 3, A Chronicle of Ancient Sunlight)

|

|

| First edition, Macdonald, 1953 | |

First published Macdonald, (seemingly at the end of November) 1953 (12s 6d net)

(‘net’ meant that the book could not be sold for less than the publisher's set price – the Net Book Agreement benefited both publisher and author. Today the author only gets percentage on the discount price sold to the bookseller, thus greatly diminishing his income.)

Panther, paperback, 1962

Reprinted by Macdonald, 1984

Zenith, paperback, 1985

Sutton Publishing, paperback 1995

Currently available at Faber Finds

Dedication:

To John Heygate

(A close friend since 1928, author of several books, Heygate inherited a baronetcy & Irish estates from his uncle in 1940.)

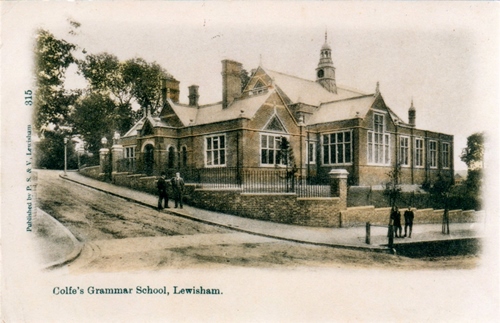

Young Phillip Maddison continues the story of Phillip as he proceeds through school. In real life this school was Colfe’s Grammar School, to which HW had won a scholarship, as did Phillip at the end of the previous volume, Donkey Boy. The school itself features rather nebulously here: it is not given a name until after Phillip has left, when we read in the next volume that it is called ‘Heath’s Grammar School’ (Colfe’s was in Blackheath, Lewisham). HW had already written in great detail of life at the school in the earlier Flax of Dream series, where it is Cousin Willie Maddison, who attends Colham School, set vaguely in the ‘West Country’.

The fact that it is the same school in both series is very well disguised, a quite amazing juggling tour de force. We are told right at the end of Young Phillip Maddison that the two ‘separate’ head-masters are ‘twin brothers’ – a neat device accounting for their similar appearance and habits. Obviously HW enjoyed this little tongue-in-cheek ploy!

Young Phillip Maddison concentrates on Phillip’s life outside school with his family and friends, and all the details that beset this sensitive, rather wayward and unpredictable boy, whose keen interest in nature is strengthened as he grows older and is able to explore the surrounding countryside. The book takes us into the heart of the life, thoughts, and feelings of a young lad growing up in Edwardian England, yet it is not ‘dated’. Everything is immediate and fresh and absorbing.

*************************

HW started work on this third volume of A Chronicle of Ancient Sunlight in May 1952 on return from a short visit with his wife Christine (and child) to his first wife, now living at Bungay in Suffolk. HW was under a great deal of strain, as always at a time of intense writing. At this point he recorded in his diary that the novel was tentatively titled:

‘The Windflower’ – ‘Not I but the wind’ (?) quote from D.H. Lawrence.

It is indeed a Lawrence quotation. It comes from ‘Song of a Man Who has Come Through’ (poetry volume Look We Have Come Through,1917):

Not I, not I, but the wind that blows through me!

A fine wind is blowing the new direction of Time.

It does not seem a very appropriate title for a book about childhood, and there is no indication as to why HW chose this. It is interesting that he was choosing a poem of Lawrence’s. That he was remembering it from a long time before is evident from the hesitant ‘(?)’. Lawrence tends to be known for his novels but he also published several volumes of poetry, and was considered one of the Georgian poets. There is a volume of Georgian poetry (Georgian Poetry 1918-1919, ed. Edward Marsh) in HW’s archive, given to him by Frank Davis (on whom Julian Warbeck is based in the Chronicle) in 1921. (HW states somewhere that he stole this from Frank – but it is signed ‘To Bootie from Frank (well-fed) 1921’.) It does not contain this poem but another one from Lawrence’s 1917 volume. So the little mystery has to remain unsolved.

At the end of May HW recorded that he was giving up writing for the summer as he was too tired and needed a break. At the same time that he was working on this book he was also dealing with the compilation of Tales of Moorland and Estuary, which was published in March 1953. In the interim he had a holiday in Ireland, staying with John Heygate at his Bellarena estate (for further details see my biography Henry Williamson: Tarka and the Last Romantic, pp. 272-76). On 2 October he recorded: ‘I re-started Book III.’ Writing continued without let-up; on 8 December he had ‘finished part I of Book III, “The Wind’s Will” after working most of last night & today. Exhausted.’ And continues to write without break – ‘I wrote all through Christmas’, and, in the notes section here: ‘Have done about 180,000 words of Book III.’

4 January 1953: I finished Chapter 17, ending in death of Sarah Turney, this morning, having got up at 4 a.m. I finished at 1.30 p.m. A very easy scene, simply written – it wrote itself. I was remembering my own grandmother Henrietta Leaver (née Turney) death.

Two days later he noted he was ‘Reading for first time “Fathers & Sons”. Very good. Turgenieff in 1860 didn’t know why women got so nervous & flabby. Or did he?’ The ‘father and son’ theme is very prominent in HW’s work – and is particularly noticeable in this volume. HW had also read Edmund Gosse’s Father and Son (1907) earlier, as he mentions it in his book On Foot in Devon (1933), where he is quite bitter about the effect of the ‘grim man of God’ and his effect on his son.

On 9 January he recorded: ‘Working. I like the book now. But it goes on for ever! I type in daylight, write by hand at night.’

He thought about changing the title to ‘An Edwardian Youth’ but for the fact that Edward VII dies halfway through: so as ‘An Edwardian Boyhood’ it became the title of Part One. But very soon his diary indicates that he is writing far beyond the present Young Phillip Maddison and is into war scenes:

I fear the book will run to nearly ¼ million words. In an age of television & motoring!

In the middle of April he again went to Bungay (where his first wife lived, while Christine & ‘Poody’ then went off to her mother’s at Ripon, Yorkshire) where he re-arranged the book’s content, revealing that another working title at this time was ‘Goodbye My Bluebell’.

On 4 June there is an entry which he indicates actually belongs to 22 June: ‘My novel was finished some days ago, or weeks; sent off for typing; corrected; and taken down to Malcolm Elwin on Monday 15 June.’(Elwin was his immediate editor at Macdonald’s; he lived across the fields from Ox’s Cross at the bottom of the cliff below Pickwell Down – next to Black Rock.)

An interesting snippet here: HW watched the coronation of Queen Elizabeth II on a television that was set up at Georgeham Village Institute – ‘a tiny set about 10” x 12”’ – so very difficult to see. He tried to get the councillor in charge to put it up higher but to no avail! (No doubt earning further black marks locally!) Afterwards he had a drink at the King’s Arms – ‘now a nice pub’.

15 June: I have not the slightest qualms about Young Phillip Maddison, a title suggested by Eric Harvey [a director at Macdonald] after John Heygate had proposed the name to be part of the title. I had many alternatives, the last of which was The Way to Wine Vaults Lane . . . I had to end at part 5, & leave out the original part 6, 4 August – 12 February, 1st return of the soldier. That will now be part I of the sequel. [Note that Part 5 also disappeared from the published volume – some firm editorial handling evidently took place!]

I know that Y.P.M. is good, sound, basic.

I wrote a new beginning last revision of all, the oak on the hill in fog: & the story wove in from that . . . Many incidents are true of my life, such as the Valentine, Mr Pye disliking me . . . & his kneading of the breasts of Helena Rolls at his magic lantern display. Also Peter Wallace, the bespectacled boy, fighting like that; & the incident of Alfred Hawkins (his real name) & many others.

By the beginning of October proofs had been read and revised. John Middleton Murry also read a set of proofs and liked the book which greatly encouraged HW. On 8 October there was a visit by Marjorie Turney to the Field:

She’s just the same: and so am I – “Polly Pickering” of the novels. She said I was a witty, comic boy. Quite a surprise to me!

By 26 October he has already finished chapter I of How Dear Is Life (note that this title was established from the start).

HW does not record the date of publication of Young Phillip Maddison, but from the date on reviews it would appear to have been towards the end of November 1953. The turmoil of its writing is not present in any way: it flows through itself and could never have been otherwise!

************************

As this volume opens it is spring 1908; Phillip is nearly thirteen years old and he is wandering home from school across ‘The Hill’ in a fog. It is the Eve of St Valentine’s Day and he is planning to send a secret Valentine card to Helena Rolls, the pretty daughter of the rather aloof family who live at the top of the road, in the only house with a turret. (A symbolic metaphor which HW did not have to imagine: it was actually so! Still there in the late 1960s, the house was subsequently demolished.)

The secrecy of this undertaking is complicated, and compromised, by the fact that he asks cousin Polly (his ‘Gaultshire’ cousin who is visiting) to draw a picture for him, which gives rise to spiteful teasing by his sister Mavis, with whom Phillip constantly bickers. The consequent furtive delivery of his card through the Rolls’ letterbox is aborted by the somewhat lecherous Mr Pye, intent on the same errand.

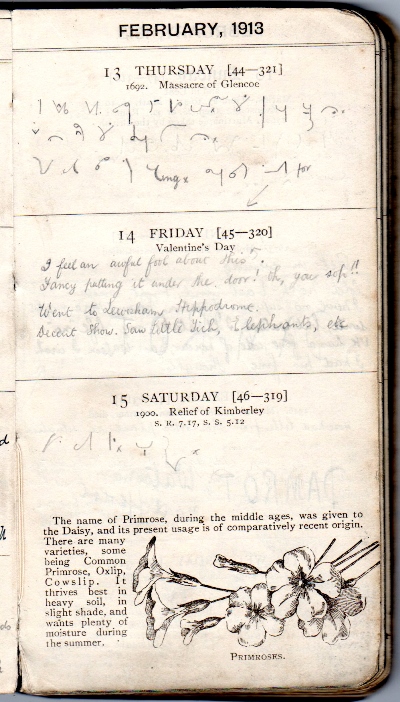

This incident is recorded in HW’s ‘Schoolboy Diary’ in shorthand code (so no prying eyes could read it!), but in February 1913, when HW was actually seventeen. The fictional version is obviously embroidered to give it more impact, but we are indeed taken right into the feelings of an uncouth youth stumbling through the first stirrings of calf love.

Phillip meets up with Horace Cranmer, the lad who comes from the poor home in Skerrit’s Road, who at fourteen is still at the Wakenham School, but is about to start work in the tanning yard at Bermondsey. The struggle of Cranmer’s life is a thread which is worth following in these early volumes. It illuminates the hardships of the poor – as does Theodora Maddison’s work as suffragette and defender of the poor – impinging on the main thrust of the novels: a sub voce background. So we are aware of it without being aware of it: very subtle.

Another boy who features prominently is Peter Wallace, who, being a good fighter, protects the timid Phillip Maddison from bullies and is prepared to fight on his behalf – although that has its repercussions in due course.

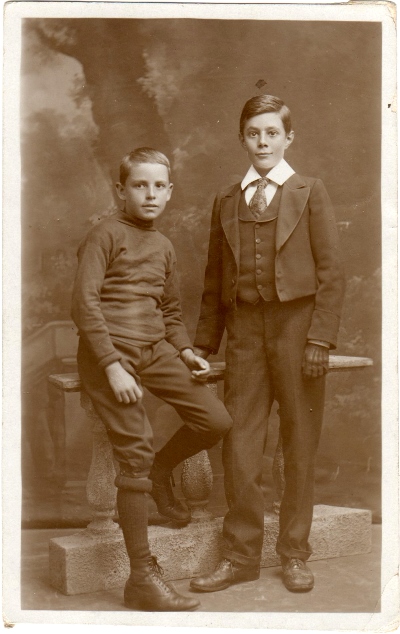

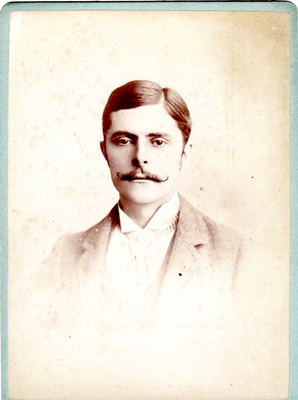

Threaded into this early part of the novel is the business of Phillip dressing up in his best clothes – his ‘Etons’ (handed down from his cousin) – in preparation for a photograph, to be properly taken in a studio. This is accompanied by teasing from Mavis, much nervous fussing from Phillip (but he takes the opportunity to fumble among Polly’s clothes), and emotion from his mother:

‘You must look your best for your photograph tomorrow, you know.’

Even his father is suitably impressed, wondering jocularly whom the strange boy is who has appeared in the house!

This is the photograph that was taken: how proud his mother must have been.

Richard Maddison is a frustrated man in many senses of the word (we note that he secretly looks at books with ‘tasteful’ artistic photographs of ladies, and he lechers after younger women). His mundane and disappointed lot in life is summed up in the sentence:

For twenty-five years Richard had been going to and from the City, and in that time, as he had estimated one recent evening while compiling his diary, he had crossed upon the flag-stones of London Bridge, in the roar of iron wheel-bands and horse’s hoofs on granite, approximately on fourteen thousand five hundred occasions.

Richard longs for a life beyond this hum-drum daily bind and grind, which he resents. The fact that he lodged at ‘Joy Farm’ before he got married has a hidden metaphoric symbolism for his married life. But he does not actually have too bad a life: he escapes on his bicycle and has several personal occupations. The main problem is probably lack of money – he cannot afford to live the life of a gentleman. He has never recovered from the peculiarities surrounding his marriage, while he greatly resents the presence of his in-laws living next door. His wife is always running back to her Papa, who gets the attention that should be due to himself.

Cycling is prominent. Richard Maddison now has a Sunbeam (replacing the revered Starley Rover) while Phillip has a second-hand Murrage’s Boy’s Imperial Model. (Murrage’s is Gamages – then a famous London store.) Father and son go off for cycle rides to various local haunts – Richard’s favourites from his earlier life, and all known to be places that HW visited frequently as a boy. But these jaunts are never really happy occasions, for Richard is always upset by something Phillip does, or does not do.

One tiny detail placed into one of the cycle rides is an echo of HW’s early and important story of the picking of bluebells by the local populace:

Some traps stood outside the Bull by the tram-stop. The ponies’ heads were held by ragged boys and men; but the cyclists went on, bells tinkling, swiftly among the gleaming tramlines. Here and there on the wood-paving bluebells lay, scattered amidst bits of paper and orange peel, banana skins and squashed horse dung.

A problem arises over Mavis and a boy called Alfred Hawkins, who are caught lying in the grass together. Mavis has been shown as being a little precocious in her behaviour with her father, who is conscious that he is in danger of responding. Phillip and Peter Wallace challenge Alfred, and Peter beats him up. When this is discovered, Phillip cowardly runs away, and is later caned by his father, who then overhearing what the trouble was about, turns on Mavis. She, terribly upset, runs away and is not found until nearly midnight. The estrangement from her father runs deep, and Mavis holds this, very bitterly, against Phillip for all her life. The psychology of this incident is very cleverly manipulated throughout the rest of the Chronicle.

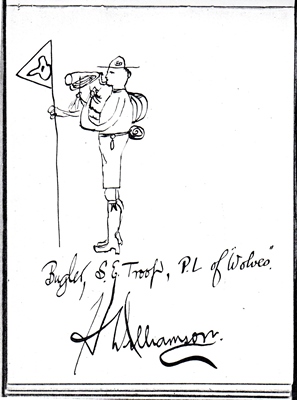

Phillip obtains The Scout, Volume 1, No. 1 (the Scout Movement was indeed formed in 1908), and totally absorbed takes up scouting, first in his own way, making his own ‘Bloodhound Patrol’ with Cranmer, Peter Wallace, Lenny Low, the rather unpleasant Ching, and a newcomer, Desmond Neville, who becomes Phillip’s best friend, along with his mother Mrs Neville (parted, as we learn later, from an unpleasant husband). Desmond Neville is based on the great friend of HW’s youth, Terence Tetley, and all the various scenes concerning him that occur throughout the Chronicle are firmly based on real life, with very little embellishment.

The enthusiasm and fun of this new activity of scouting is portrayed with exact and authentic detail. After a while the boys join the official Scouts (except poor Cranmer, already working but not wanted anyway) under local scoutmaster, Mr Purley-Prout. There is great fun in the scenes of the Whitsun Camp, but Purley-Prout, unfortunately interested in little boys sexually, takes Lenny Low into his tent and interferes with him, giving him money. When this inevitably gets found out, Purley-Prout has to leave the district. (Such a lenient solution is highlighted by the spate of revelations of cover-ups of this kind of behaviour in our own recent times.)

As Phillip becomes adolescent he has the first stirrings of sexual feeling, and this is shown in various scenes of fumbling experiments (some with his willing Gaultshire cousin Polly Pickering – i.e. HW’s Bedfordshire cousin, Marjorie Boon) which are contrasted with the attitudes of adult moralising. But there is always the overshadowing, awful example of Phillip’s uncle, Hugh Turney, shown to be rapidly deteriorating as syphilis spreads through his system. But talk of sex is taboo. It cannot be openly mentioned: in the early years of the twentieth century the constraints of Victorian morals still hold in these middle-class circles.

Hetty once again takes her children to Hayling Island for two weeks. Philip no longer finds it quite as exciting but makes his own entertainments, which include several visits to the ‘Merry Minstrels’ show where a beautiful fair-haired girl:

. . . with pink frock and large pink hat with pink ribbons hanging down it, sight of whom made him forget Helena Rolls.

The Williamson family visited Hayling Island for their two weeks’ summer holidays for several years in the early 1900s. (For further background see Robert Walker, ‘Henry’s Hayling Holidays’, HWSJ 46, September 2010, pp. 15-28.) A later holiday at Whitstable is a total disaster, due mainly to the tidal mud stinking of sewage!

Phillip catches scarlet fever, an extremely dangerous infection in those days. He is sent away to the fever hospital for isolation, the normal practice. That would have been a daunting experience for a young lad. The description of this event, with its attendant Lunatic Asylum scene, is one of those ‘social history’ markers that are woven through the novels and shows how grim life could be in those days. Hetty takes him to Brighton to recuperate. There is no evidence that young Harry ever caught scarlet fever, but the disease was a real threat until after the Second World War. He probably actually had measles or some such rather badly.

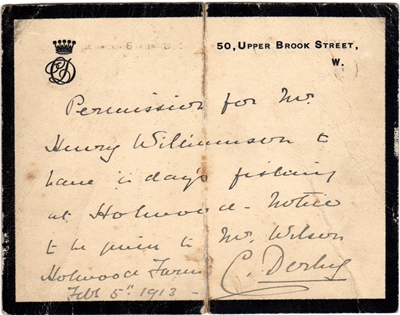

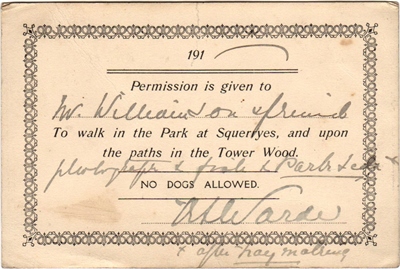

The chief occupation – and pleasure – of HW’s young life lay in his wanderings in private parks and woods, for which he gained permits by writing to the owners. He learnt a great deal by talking to the gamekeepers of these various ‘preserves’ as he called them, and it was possibly where he gained his objective view about nature ‘red in tooth and claw’ which is so obvious in those earlier short stories.

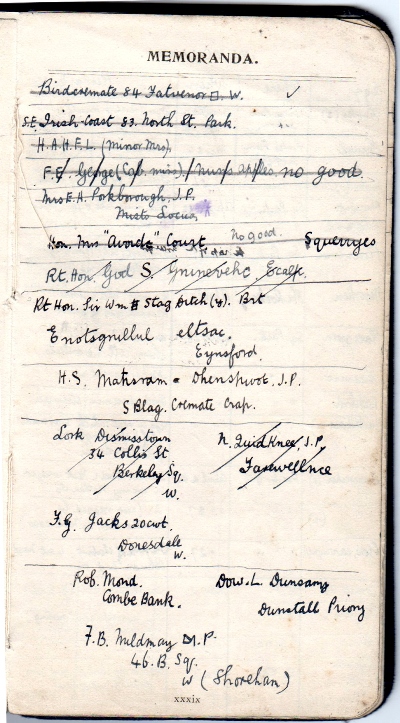

In 1913 he kept a ‘Schoolboy diary’ (printed by his grandfather’s stationery firm) and further recorded every visit he made in school exercise books. This ‘Boys Nature Dairy’ was printed verbatim in the 1933 edition of The Lone Swallows. It shows the promise of the writer-to-be, not least the tenacity of purpose involved. He made a code to hide the names of those he had written to for permits from prying eyes.

This is all part of Phillip’s boyhood in this novel: a most vivid and charming ‘remembrance of time past’. The rivalries of the boys, their quarrels and intense friendships, joys, worries, and emotions make an intense bond with the reader.

(Much background can be found in HWSJ 38, September 2002, pp.10-58, and HWSJ 44, September 2008, pp. 4-70, both of which contain various articles illustrating HW’s early years and how these fit into his writings.)

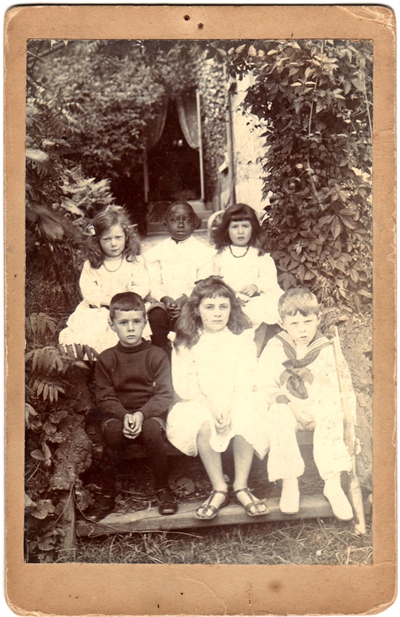

As Young Phillip Maddison continues, there is great excitement as Charlie Turney, brother of Hetty, who had left home many years before after a violent quarrel with his father and has been working in Canada and South Africa, now returns home (he says in time to see the coronation of George V: Edward VII died on 6 May 1910 – the date of the coronation was 22 June 1911). He brings his wife Florence (Florrie), previously a singer, and children Petal (the same age as Mavis, thus born 1897) and the younger Tommy: accompanied by accoutrements of African life, including Kimberley, a black boy. Charley and family stay with the Turneys, but once the euphoria of reunion is over the old animosity between father and son soon resurfaces. Inevitably, there is speculation as to whether Kimberley is Charley’s son, but precocious Petal tells Phillip that it can’t be proved.

|

| HW and his South African cousin, Tommy Leaver |

|

| Family group, with Kimberley |

Charley, out of kindness to Hugh, takes him to Brighton, the old holiday haunt of the Turney family, the is, ‘Mama and the five children’, ‘The Old Man’ only joining them at the weekends. He invites Gerry, whose father had died in the Boer War, and Phillip to go with them. It is not an entirely happy outing, Hugh being rather distraught at his own situation. He wants to be left alone to write out his thoughts – to be a great novel on ‘the maniac power of fathers over their sons . . . the hidden malaise of modern society’: obviously HW’s own thoughts on the subject. However, the boys enjoy themselves with the usual seaside attractions of that era and have a jolly day.

|

| HW's uncle, Hugh Leaver |

When the (perceived) problem over Kimberley surfaces, the rather histrionic Florrie tries to commit suicide. The ensuing quarrel between Charley and his father upsets his mother so much that it brings on a stroke, from which she dies. After a bit Charley decides to move out of his father’s house: Phillip tells him that Joy Farm is to let (reminding Richard of his own very happy time there before the cares of marriage and family life overwhelmed him), and so the unrepentant family move there and find it very congenial. However, restless Charley decides they should return to South Africa, but first plans a trip to New York for himself and Florrie, booking passage on the Titanic.

One of the most intriguing and evocative scenes in the book is the ‘Jaunt to Belgium’, related towards the end. We learn that Mavis is attending the Ursuline Convent at Thildonck, Wespaelar (and has been for some time), and as she is not allowed to travel home for the Easter holidays, Thomas Turney, now free to travel, decides to take Hetty and Uncle Joseph, together with Phillip and Petal, who is to attend the convent herself (while Tommy is to be sent to boarding school in Brighton). Thomas Turney is paying for this, and for the education of others of his grandchildren (but not the Maddisons).

The journey is described in some detail (including a little fairly innocent and awkward sexual liaison between Phillip and Petal). But when they reach the convent all is softness and smiles. Phillip meets Mère Ambroisine, who had known his mother when she had attended the school. Needless to say, this is all based on real life. HW’s mother had indeed attended the Convent at Thildonck, where the Mother Superior had been Mère Ambroisine.

The goodness and sweetness of the nuns (Ambrosia – food of the Gods and divinely fragrant: one feels HW must have made the name up for this purpose, but that was her actual name within the religious community) envelops Phillip and shows him as his true inner self. Phillip is very conscious of the importance of the moment, as was obviously young Harry. It is a moment of stillness at the centre – a moment to be savoured before the real world takes over again and Phillip becomes his normal perversely naughty self. This is a quite interesting point within the overall theme of the novel: goodness begets goodness.

(For an excellent article on the background to Thildonck Convent see Tony Jowett, ‘A Jaunt to Belgium’, HWSJ 39, September 2003, pp. 85-96.)

As the family party return to England they see the news-bill headline announcing that the Titanic has sunk (on the night of 14/15 April 1912). But after the first panic, there is a message to say that Charley had missed the boat and had sailed to America on another. Thomas Turney pronounces one of his pompous sayings, this time with unintentional irony: ‘I always said Charley would be late for his own funeral.’

Phillip is invited to stay with his cousin Willie Maddison at the family home at Rookhurst, thus reprising the visit of Phillip which appears in Dandelion Days. Here this exciting holiday is glossed over in one paragraph. Possibly HW felt it difficult to maintain the strange schizophrenic mirage.

The end of Phillip’s schooldays looms. We are told about Mr Graham, the historian, once a pupil at the Heath School, who took a keen interest in everything that the boys did, especially the sports. Mr Graham was Leland Duncan, a distinguished local worthy, who indeed took an interest in the boys, and was very kind to HW. (See HWSJ 38, September 2002and HWSJ 44, September 2008 as before.) And finally we meet ‘The Magister’, as the head was known: as irritated with Phillip as his twin had been with Willie, understandably!

Phillip’s future has to be resolved. Out of sheer nerves and lack of any social experience he messes up an interview with his Uncle Hilary, who wanted him to farm in Australia. Instead his father arranges for him to have an interview at the Moon Fire Insurance Office, where he himself works. Phillip has a new suit for the occasion. He is told he will be taken on, on probation, on the following Lady Day, 25th March, at a salary of £40 a year. That date, to Phillip’s elation, was still two months away: he could continue his country pursuits.

The final scene of the book involves the ‘Bagmen’ – the name given to those boys in the ‘Commercial Class’ (that is, not going on to university). Note that Phillip does not learn shorthand – but HW certainly did! As the boys leave school, so they have a final ‘Bagmen’s Outing’, together roaming the countryside haunts of their boyhood, those places that have threaded the tapestry of these first three volumes of the Chronicle: Whitefoot Lane, the Seven Fields of Shroften, Cutler’s Pond, etcetera, remembering past excursions. They end up at the Hippodrome, where there is a girl with pink stockings and shoes with pink bows (‘pink’ was obviously the epitome of feminine charms!) . . . Phillip wants it to go on forever but:

It was over, his boyhood was over.

The phrase echoes the one that HW wrote at the end of his 1913 ‘Boy’s Nature Diary’ after the end of the First World War:

And Finish, Finish, Finish, the hope and illusion of youth,

For ever, and for ever, and for ever.

At home Phillip tells his father he had been to the Seven Fields: Richard, lost in thought, remembers his brief honeymoon there with Hetty, and then Phillip’s difficult birth. Phillip looks at the book written by Mr Graham that is given to all boys as they leave. Hetty comes in with her darning, and for the briefest of moments, the three are at peace with each other.

*************************

Index to 'The London Trilogy':

Between 2000 and 2002 Peter Lewis, a longstanding and dedicated member of The Henry Williamson Society, researched and prepared indices of the individual books in the Chronicle of Ancient Sunlight series, with the first three volumes being indexed together as 'The London Trilogy'. Originally typed by hand, copies were given only to a select few. His index is reproduced here in a non-searchable PDF format, with his kind permission. It forms a valuable and, indeed, unique resource. The PDF is in two sections:

'The London Trilogy': An Index — Aerated Bread Company to Maddison, Theodora

'The London Trilogy': An Index — Maddison, Phillip Sidney Thomas to Zoo

*************************

There is quite a large file of cuttings but an entire lack of any from the major newspapers, which is somewhat puzzling. The book cannot have been totally ignored by them – so I have to presume that these were placed elsewhere and have disappeared. It would be useful, if anyone has any knowledge of any such reviews, if they would let us know via this website.

The North Devon Journal Herald (F.H.K.),17 December 1953:

Mr Williamson’s new novel is in every sense a continuation . . . carrying it forward from puberty to adolescence, and setting it down at a convenient place for pausing as Phillip himself is taking leave of school.

But the book is not primarily concerned with . . . school . . . the action is directed away from the classrooms and towards the family circle. . . .

In young Phillip himself the change is more noticeable. Adolescence has begun, and here we are given a penetrating study of the uncertainties and frustrations of the boy-youth.

In Mr Williamson’s writing may be found a clear understanding and a keen observation of human behaviour. The irritation of one nature chafing against another is described with such realism that one can feel the friction. This is no pleasant fiction of middle-class living in the late Edwardian era, but a story full of the very matter of life.

Eastern Daily Press (Adrian Bell), 11 December 1953:

Liveliness is also a characteristic of . . . This relates the life of the son of Richard and Hetty during his grammar school days in the reign of Edward VII. It is a tale as full of incidents as the life of a high-spirited boy can be. Incidents . . . that are shattering at the time begetting family tensions and troubling neighbourly relations. There are feuds with gangs of boys on the wasteland on the edge of the suburb, the emotional disturbances of earliest awareness of the other sex, scouting and contacts with nature. Much of the story read to me like fitful recollections of my own boyhood, whereby I judge Mr Williamson good and true to life.

Recorder (James Hanley), 10 December 1953:

Young Phillip Maddison is . . . third volume of this tremendous study of a human being. . . . [it] is a comprehensive story in itself, of the boy, Phillip. . . . had been a dear little child, innocent, loving and ardent, but something has gone wrong in his relationship with his father . . . and now he has developed into a personality of rather grievous complexity, always in scrapes, sometimes unwittingly, but more often because he could be quite extraordinarily naughty.

Being highly imaginative his defaults exceed those of normal children. . . . There emerges an individuality, complex, passionate, disobedient, cowardly, a liar and yet with all his faults, somehow lovable.

How well Mr Williamson conveys all the secret thoughts and doings of small boys, living lives that are all heights and depths, and never a humdrum centre. Magically he suggests the era by subtle description; the types of road, the makes of car and bicycle, the prices of commodities, the fashions of the day, as well as by the thoughts and conversations of the many characters, both child and adult, in this long and deeply fascinating book. This is a world of the past, yet how it lives?

Sphere (HW has added the name: Vernon Fane), 16 January 1954:

[HW’s] long new novel about the life of an English middle-class family . . . is a sincere if verbose account of childhood in one of the new London suburbs of Edwardian days and it is worth your attention for two reasons: one, that Mr Williamson writes about boys with almost as great a perception as Mr Booth Tarkington in the past, and two, that, being the naturalist he is, he cannot help making even the smallest passage of a country glimpse other than an enchantment.

St Martin’s Review (marked by HW as by William Kean Seymour), January 1954:

. . . now we have a further 416 pages of the saga . . . in which the father-burdened boy is carried on to his school-leaving and imminent clerkship in the Moon Insurance Co. I say “father-burdened”, for here, as in “Donkey Boy” we see what can spring in character-development from a state of emotional frustration existing between the parents. Poor Richard, the father, is a psychological mess, harbouring grievances against the world, turning inward on himself; lonely, punitive in spirit, making an article of faith out of his lonely bicycling and cold baths: pompous and admonitory in expression and, all in all, a “pain in the neck”. . . . [This also reacting on Hetty and the three children.] . . . That is the psychological “set-up” but within that framework is a rich pulsating story. The marvel . . . is the exactitude of his recollections of the London scene when Edward VII was King. Steam buses and “electric theatres”, the first L.C.C. trams . . . but also the suburban green fringe, now lost in housing estates. [with all the naturalist’s detail] . . . There are tragic streaks in this new novel, and some matters are discussed with refreshing frankness. A design emerges from this “Maddison Saga” – like a magic mirror in which we may see the little London suburban world of Edwardian humanity.

Current Literature (Allen Street), December 1953:

Love in the sexual sense is not a subject that is considered fit for conversation or discussion among the characters of . . . in Edwardian England among respectable middle-class characters who live on the fringes of suburban London. Mr Williamson draws in meticulous detail the drab, genteel environment in which Phillip grows up, his youthful zest for life unquenched, in spite of frequent cataclysmic despairs and his ever-present fear of his father. It is this father-son theme which is the core of the book, and from the unhappy relationship that exists not only between Phillip and his father, but which existed also between Mr Maddison and his father can be traced the distortion and warping of character that begins even in early childhood. Phillip’s father is a pitiful figure drawn with merciless clarity of outline by the author. He dominates a story which is essentially sad in its picture of frustrated lives and buried hopes, but is relieved by the joyful spring-like moments that occur in every boy’s life and which are here described with sympathy and insight.

Yorkshire Evening Press (S. P. B. Mais), 26 November 1953:

Henry Williamson, as I have always maintained, is something of a magician. I am quite sure that no other writer could have kept me interested in the thoughts, feelings and actions of a 13-year-old boy of the Edwardian period for over 400 closely packed pages. . . .

The curious thing is that there is practically no story. Everything the boy does is grist to Mr Williamson’s mill, and he meanders along in so leisurely a fashion that our patience is often tried. . . . The outstanding merit of this very satisfying story is that we see life through the eyes of a boy in his early and middle teens.

There is no attempt to make Phillip a hero. . . . It is Phillip’s reaction to the life of the country, the seasons of the year, his father, mother and friends that absorb our attention. . . .

The interest and excitement, which are very real, lie in watching the growth of the boy’s mind and soul, and this is developed with a certainty of touch and quietness that mark the true master of his craft.

This Maddison saga is solid and built to last. The tempo may be slow, but the result is an enchantment which will, I believe, be shared by every reader who has not forgotten his or her own youth.

Mais also wrote a much shorter review for the Oxford Mail, 4 December 1953:

He takes us back 50 years to watch the spiritual and physical development of an unduly sensitive and awkward 13-year-old boy of the Edwardian era, suffering frustrations under a too rigid father and a spoiling from an over-fond mother. The merit of this extremely detailed story is very high.

John O’London’s Weekly (Richard Church), 11 December 1953:

Henry Williamson has none of the art of the two writers already discussed [William Cooper and Margery Sharp]. He is rather more the naturalist, turning his observant eye from field and hedgerow to the human scene. . . .

The fidelity to literal fact is astonishing. The reader recognises again and again little details that recall incidents and objects now loaded with trailers of memory. . . .

But Mr Williamson continues in laborious prose style. .. we must take his work as we find it, amorphous, pedantic, but remarkably faithful in its recollection of scene, mood, and relationships.

The Scotsman (unnamed), 7 January 1954:

[some preliminary remarks] . . . In the earlier novels the circumstances which conditioned the outlook of Phillip’s parents were described, and now here we see some of the consequences – the boy’s secretiveness, his frustrations. His outlook is transformed when he can escape to the country. . . .

Mr Williamson makes this contrast moving, and the scenes of family life are done with sensitive understanding. Despite these virtues, however, the novel fails to grip the imagination . . . and too much of the narrative seems tedious and plodding.

Manchester Evening News (Julian Symons), 10 December 1953:

Henry Williamson is famous for . . . he is less well known as a novelist . . . a truthful and sympathetic portrait of childhood.

Truthful, for young Phillip Maddison is not altogether a likeable boy . . . But sympathetic for Mr Williamson convinces us that Phillip is an essentially innocent and idealistic boy: a little precocious perhaps, but thwarted chiefly by a lack of understanding in his home. . . .

. . . The merit of Mr Williamson’s portrait is that he shows Richard Maddison as pompous and dull, yet manages to convey also his awkward good intentions and genuine affection for Phillip. . . .

. . . the accumulative effect of many everyday occurrences is to create a rounded portrait of a prickly, sensitive young boy. That is something rare in contemporary fiction.

Liverpool Daily Post (Brother Savage – i.e. a member of the Savage Club to which HW belonged), 28 November 1953. A book about Winston Churchill heads the list of this review column but HW gets a good percentage of the space:

Henry Williamson, farmer as well as novelist, has settled in Devonshire again after a lengthy sojourn in Norfolk, and the fact that he has been writing prolifically ever since he returned there shows that he feels thoroughly at home in the West. . . .

The mental and emotional development of young Phillip . . . but Phillip Maddison has a life of his own . . . the author of “Tarka the Otter” has not been claimed as “our best living Nature Writer” for nothing.

Irish Independent (I.H.), 6 March 1954:

The Only Son

This novel reads very like an autobiography, the story of an Edwardian boyhood, describing those well-remembered seasons, disturbing, awakening years, the scars of which . . . will remain for a lifetime. . . .

One conclusion that can be drawn from this novel is that children brought up in the city and its suburbs suffer from a nameless blight, a handicap not described in any medical book and the victims of which generally never know that they have had it. Much truth there is in this theory. Phillip the boy only felt at peace within himself and real happiness when he discovered the interests that were to be found in field and hedge and tree. . . .

The Birmingham Post (R. C. Churchill), 22 December 1953:

. . . There is a loving detail about the record of the boy Phillip in the years before 1914 that makes an ordinary existence of hopes and frustrations youthful joys and fears, remarkable interesting.

Calcutta Statesman (unnamed), 17 January 1954:

In “Young Phillip Maddison” Henry Williamson has attempted a very difficult task indeed: a simultaneous presentation and representation of an adolescent boy living in a London suburb towards the beginning of this century. One is swung, with the author, between an understanding of his hero, to a faintly malicious view of him, and back through varying layers of common sense and text-book psychology to a genuine, if suspicious, appreciation of his trials and tribulations. The subject is interesting; few writers have attempted such a piecemeal stripping of that particularly situated generation that holds so many positions of diverse importance at this moment.

Evening News Glasgow (T.O.), 5 February 1954:

. . . [HW] is now dealing with Phillip rather than his worried, self-tortured father, Richard. The son is introspective but happier than his parent and in him the love of Nature has found an unhindered outlet. This enables Mr Williamson to combine his own brilliant descriptive powers in this direction with Phillip’s growing vision. . . .

. . . One breathes here genuine country air combined with acute human observation. Undoubtably one of the best novels of the passing year.

Egyptian Gazette, Cairo (Laurence Meynell), 6 December 1953:

THE WEEK’S NOVELS [headed by Young Phillip Maddison]

The enchantement (sic) which distance is said to lend to the view certainly falls like a spell over . . .

It is a long, closely knit book, mainly concerned with the small details of family life. The principal character is young Phillip Maddison, whose emergence from grubby boyhood into adolescence is tenderly and touchingly represented.

Gas lamps, bicycles, and Marie Lloyd on the ‘halls’ set the tone of this seemingly artless yet actually very skilful tale. . . .

Paisley and Renfrew Gazette (G. H. Bushnell), 6 February 1954:

Brilliant Story of the Past

. . . [a halcyon period which few novelists have dealt with adequately] This story . . . is superlatively good; a brilliant painting of a day that had gone. . . . It is a grand story, which holds the reader from page to page and at the end makes him cry for more. . . .

. . . With a masterly touch that arouses great admiration Mr Williamson reveals why and how that search was doomed and in doing so adds another great novel to his name.

Three items deserve full viewing as follows:

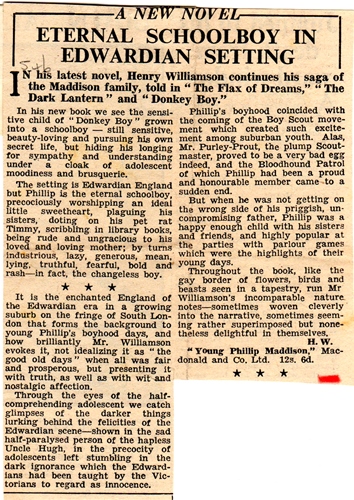

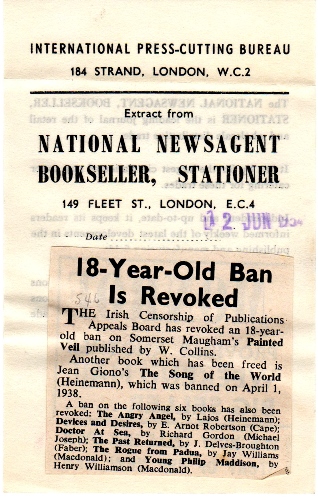

Oldham Evening Chronicle (H.W. – surely not our HW!), 11 December 1953:

An odd historical curiosity:

And a final superb review from a local source:

Beckenham Advertiser (Ben Newing), 11 November 1965:

**************************

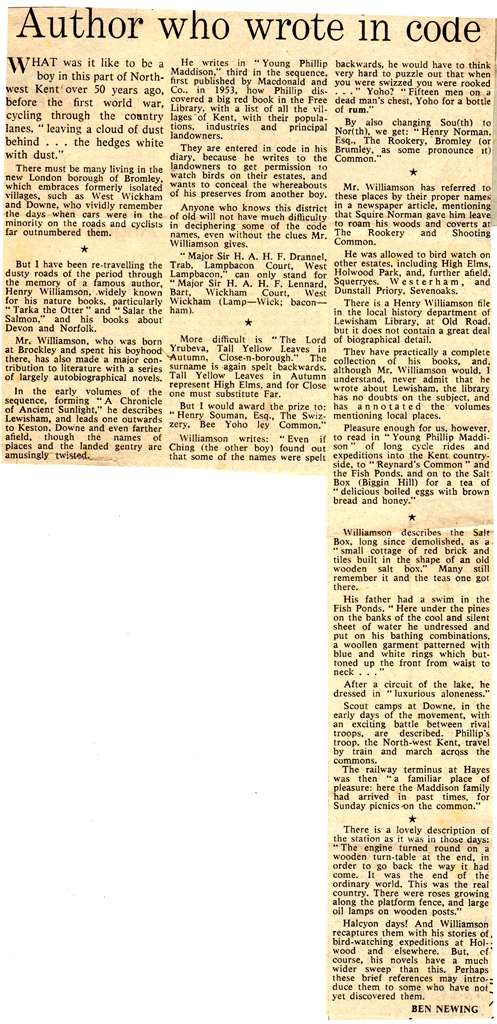

The dust wrapper of the first edition, Macdonald, 1953, designed by James Broom Lynne:

Other editions:

|

|

|

| Panther, paperback, 1962; and back cover | ||

|

|

|

||

| Macdonald, hardback, 1984 | Zenith, paperback, 1985 | Sutton, paperback, 1995 |

Back to 'A Life's Work' Back to 'Donkey Boy' Forward to 'How Dear Is Life'