THE LONE SWALLOWS

|

|

| First edition, Collins, 1922 | |

First published Collins, 1922

(Matthews states: ‘?July 1922’ – HW’s copy is inscribed: ‘Author’s private copy. 27/8/22’)

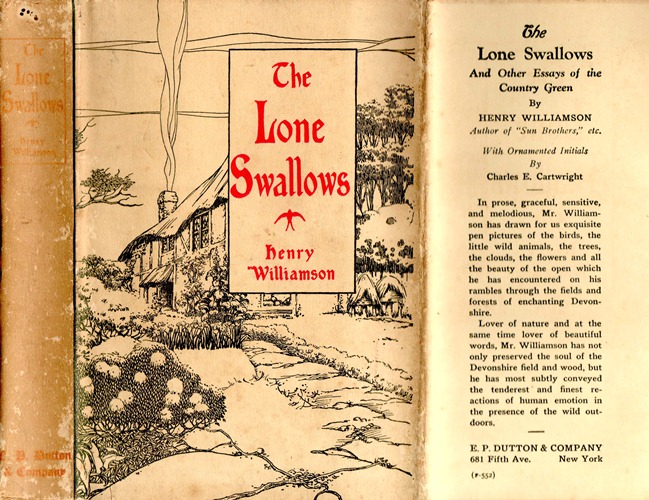

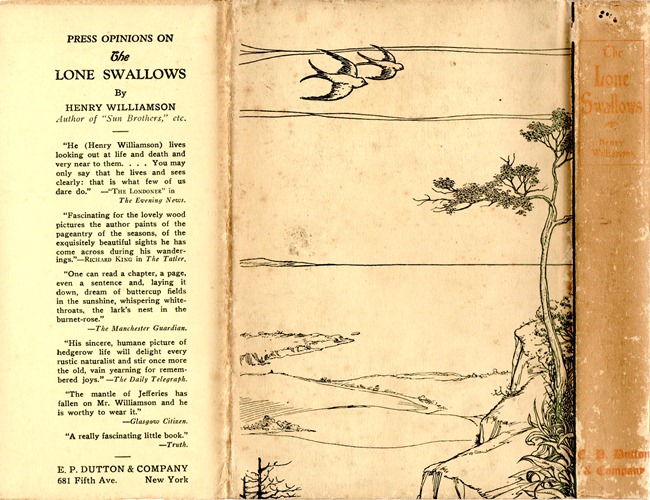

Dutton, USA, 1926

Major new revised edition illustrated by Charles F. Tunnicliffe, Putnam, 1933

Various other editions with more minor changes – see Hugoe Matthews’ Henry Williamson: A Bibliography

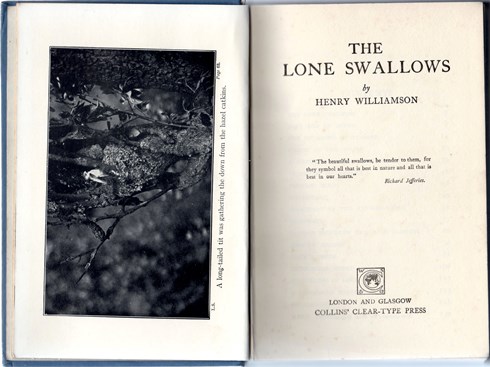

‘The beautiful swallows, be tender to them, for they symbol all that is best in nature and all that is best in our hearts.’

Richard Jefferies

Quotation on the title page of the first edition. Later editions omit the quotation and state: ‘Dedicated to Richard Jefferies’.

The Lone Swallows is HW’s second published book, coming between The Beautiful Years and Dandelion Days. The book is a collection of nature essays, most of which had already been published in newspapers and magazines: they are HW’s first attempts to ‘describe the common sights and sounds of the English countryside’, as he stated in his own ‘Compiler’s Note’ that fronts the first edition.

The first edition had no jacket as such – the covering being a flimsy fragile transparent paper wrap, very quickly disintegrating (one archive copy still has this intact).

HW offered the dedication to Lois Martin, a girl he had met towards the end of 1921 (and who was the immediate consolation for Doline Rendle’s aloofness), almost certainly in London where he appears to have spent Christmas, returning to Georgeham on 14 February – seen off by his mother and Lois. His 1922 diary proper opens: ‘WILLIAM LOVES LOIS’. Lois was ‘small, red, musical’ and was the basis for Diana Shelley in The Pathway. Lois was actually very clearly not really interested in HW but kept him dangling. Having not heard from her for a month since returning to Georgeham he received a letter on 17 March: ‘I love you very dearly, you know.’ The diary entry for 21 March states: ‘Wired Lois the dedicatee of “Lone Swallows”. She replied “By all means”. Damned ill-bred & callous.’ Returning to London on 29 March to see her (at the Tomorrow Club), he found that she was ‘two-timing’ him, and was utterly miserable and ill; and that ended the relationship. It would thus appear that the role assigned to Diana Shelley in The Pathway is greatly enhanced from the real life situation. Returning to Georgeham, he immediately met Mary Graham Stokes and rest of the family, which is noted in his diary on 8 April: Lois no longer occupied his thoughts.

Richard Jefferies, it might be argued, was a far worthier and apposite dedicatee.

The stories of the first edition, by default, have to have been written before the end of 1921, so, apart from those items written for the Weekly Dispatch (six short ‘Country Week’ pieces and the ‘On the Road’ column – collected and edited by John Gregory in 1969, with HW’s approbation, and published by the HWS in 1983; e-book 2013), these stories do indeed comprise HW’s earliest published writings.

These pieces, combining short tales of country adventures with beautiful descriptive phrases, realism with poetic simplicity, are a charm of prose poems of lyrical and minutely observed details. They have a freshness that belies their period flavour: they also hold a message that is perhaps even truer for us today than it was when they were written nearly 100 years ago.

HW sets out in that original ‘Compiler’s Note’ a short but very clear statement of his thinking, his burning vision, of that time: perhaps the only really clear statement he made. It is this credo that underlies the whole of The Flax of Dream, but where (perhaps because of its lengthy novelised form) it becomes diffuse and frequently unclear. One tends to read those novels for their own sake rather than for any covert message. Here it is stated with clarion clarity, although it has little apparent relevance to the actual stories in this book (except perhaps one). But if you want to understand HW’s thinking at this time – and indeed all his life, for this underlying message is reiterated in the later series, A Chronicle of Ancient Sunlight – it helps to have read this introductory statement:

My own belief is that association with birds and flowers in childhood – when the brain is plastic and the mind is eager – tends to widen human sympathy in an adult life. The hope of civilisation (since we cannot remake the world’s history) is in the fraternity of nations, or so it seems to myself, whose adolescence was spent in the war; the hope of amity and goodwill of the nation is in the individual – in the human heart, which yearns for the good and the beautiful; and the individual is a child first, eager to learn, but unwilling to be taught. Therefore it would appear that the hope of civilisation is really in the child. Sometimes heredity may be too great a handicap, but a sweet environment is a gradual solvent of inherited vice; at least it will prevent hardness, whence springs un-understanding, and hate.

Possibly HW, sandwiching this book between the first and second volumes of The Flax of Dream, presumed readers would apply this message to the other work. Indeed, in his own mind, he may have made no difference between the various books: they were all whirling around in his mind at the same time.

Matthews, in his Henry Williamson: A Bibliography (2004) , gives the basic original publication source for several of the pieces, but a little flesh can be added to those facts from perusal of HW’s intimate folio-sized journal of the early 1920s, which I refer to as his ‘Richard Jefferies Journal’ (RJ Journal) as it is dedicated to Richard Jefferies (see AW’s biography Tarka and the Last Romantic, p. 71-2, where the title page is reproduced). The influence of Richard Jefferies’ writing and philosophy on HW, particularly at this early stage of his writing career, has been well documented over the years and hardly needs reiteration here. HW took the title of this book from his mentor, as we see from the title page quotation, and his opening essay ‘The Lone Swallows’ tells us of the so very early arrival of the first two swallows of the year, joyously celebrated by all.

In 1920 HW, aged 24, was still living at the family home at 11 Eastern Road, and had been working as an advertising canvasser on The Times from early January, and working hard on his first novel in his spare time – using a room in the house next door belonging to his maternal grandfather in which to work. He had met Doline Rendle (a cousin of Mabs Baker, with whom he had been in love in 1919, who was the model for Eve Fairfax in The Dream of Fair Women), and was now in the throes of desperate unrequited love for this beautiful, sympathetic but aloof twenty-year-old girl. He first mentions Doline in the RJ Journal on 17 April: ‘I am constantly thinking of a girl I met who is more like me than anyone I have yet met.’ By 1 May, ‘she is the one [I have been waiting for]’.

One of the earliest references in the RJ Journal to any of the stories included in The Lone Swallows is 17 May 1920, where there is a long essay entry headed ‘The Night’, opening:

Against the deep blue of the sky a little money-spider was taking a line from one veined hazel leaf to another. . . .

The Journal entry dated 1 November 1920 states: ‘Austin Harrison has published “The Night” in this month’s English Review.’

HW must surely have been very gratified. The English Review was a prestigious literary journal, founded in 1908 by the well-known writer Ford Madox Ford, who published among others, Thomas Hardy, Henry James, H. G. Wells, Wyndham Lewis, and the poems of D. H. Lawrence. Ford’s successor was Austin Harrison, who was to resign in 1923. (In 1937 this magazine was absorbed into the National Review.) HW’s essay caught the attention of the poet John Helston, who sent him the MS of a poem in gratitude – and they certainly became friends at that time, as there are a couple of slim volumes of Helston’s poems in the archive.

This story becomes ‘Midsummer Night’ in The Lone Swallows (LS, 1922, pp.136-144). It is not altogether word for word, but there are really only very minor changes from the RJ Journal MS. The printed essay is dedicated ‘To G.E.R.’ – i.e., Gwendoline (Doline) Rendle – although by the time the book was published the ‘Doline’ episode was over.

In his ‘Compiler’s Note’ HW ends: ‘It was on a Sunday in May 1920, in a tramcar at Catford, a south-east suburb of London, that the seed of this thought [as quoted earlier] was sown by the sight of children returning to the slums after a day in the country. How eager they were: and how their parents were happy! Immediately afterwards, in a visionary fervour . . . I wrote “London Children and Wild Flowers”, which Austin Harrison published, with Walter de la Mare as god-parent.’

‘London Children and Wild Flowers’ (LS,1922, pp. 68-81) evolved from a real event described in a long entry (over 3 foolscap pages) in the RJ Journal, dated 2 May 1920, which opens: ‘Went into Foxgrove this evening’: but first the poignant entry for May Day itself:

I went near the long-tails’ nest (poor old Charlie – killed at Beaumont Hamel in 1916 – “gone like the celandine from the meadow” – used to call them “long-tails”) . . . [These are long-tailed tits.]

In the margin is a note in red-ink (one of a series that HW wrote in 1947) explaining that this is his cousin Charlie Boon: this again emphasises that constant background of war and death in his mind. The next day he went into Foxgrove, one of his childhood haunts, and after an opening descriptive passage noted:

. . . All the paths are beaten by the passing of many recent feet, and what bluebells are left by the swarming hordes from Deptford, Woolwich, Camberwell and Shoreditch are either lying crushed into the leaf-mould or dropped on the paths. . . .

At Southend Pond hundreds of people were waiting for the trams [all carrying bluebells] . . . and all their faces were happy. . . .

And I thought “You little slum creatures, so happy and joyous, gazing at your bluebells and your minnows, you have been happy. I – selfish, egotistical I – was angry because you had been in the woods. But I am glad, because you dwellers in the smoke and the grime have been very happy. The atmosphere of the tram seemed quite different and I felt tranquil and serene as I proceeded to my home.

This story was published by Austin Harrison in The English Review (May 1921) as ‘The Passing of the Blossom’, dedicated to Walter de la Mare. Just before he had left London for Devon in mid-March 1921, HW had been to an ‘At Home’ at J. D. Beresford’s – Beresford, a well-known writer and respected critic, member of the Tomorrow Club, in his position as reader for Collins publishers, had recommended and arranged the publication of HW’s first book by his firm. (‘At Home’ gatherings were a convention of society in those days.) HW’s journal entry (not dated but about 12 March 1921) states:

A few celebrities present, including Walter de la Mare, J. C. Squire, Storm Jameson, Violet Hunt, Rose Macaulay, St. John Ervine, May Sinclair, and Mrs. Dawson Scott . . . Walter de la Mare is a nice fellow; he didn’t know much about nature study; he didn’t know the difference between a coltsfoot and a celandine. However, his poetry is, I think, really beautiful; he is one of the rare ones. I got permission to dedicate ‘The Passing of the Blossom’ appearing in the May English Review to him.

Walter de la Mare wrote to HW on 26 April: ‘I am looking forward very much to “The Passing of the Blossom” and proud to be its godfather’. And after its publication:

. . . What a delight it has been to have, & read, your paper in the English Review. It is – if I may say so – a fresh and living piece of writing, & the first I hope, of many. The only quite insignificant criticisms that occur to me – if you will forgive them – are ‘the little poet’. Somehow it doesn’t seem to be a compliment to the long-tailed tit; and the ‘dear children’ – the word here hasn’t quite body enough. The whole thing is delightful in thought and feeling; I do hope you will let me know when more of your work appears. It’s a proud godfather that writes; & he treasures the owl. Yours very sincerely, Walter de la Mare.

Such kind encouragement from such an eminent writer must surely have been balm to HW’s constant anxiety and extreme nervous state. HW also went to a party given by Walter de la Mare, there meeting his son Richard, who was to become a great friend, his best man at this marriage, and in due course, his publisher.

On 2 July 1920 HW noted, ‘Wrote essay on The Meadow Grasses’. This essay (LS,1922, pp. 82-95) is dedicated (To B.E.H.T.), who I think is the mother of Terence Tetley, the great friend of his youth – Mrs Neville of the later Chronicle of Ancient Sunlight – with whom HW found much solace during his young days, her nearby flat being a place of refuge from home problems. This story is very lyrical, very rural (mixture of Richard Jefferies and Thomas Hardy). The ending is wistfully longing:

I have come to know other meadows now, but they can never be the same. I lie in the flowery fields, seeing the quaking-grass against the sky, and a wild bee swinging on a blue columbine, while a lark rains joy from on high. These return, these are eternal; and with them a voice that is silent, a colour that is faded.

8 November 1920: Rough notes for Essay on Autumn (Foxgrove).

This was 'Days of Autumn' (LS, 1922, pp. 166-181), another lyrical essay based on a meadow, but in a different mood.

On 23 December HW recorded, ‘Austin Harrison is publishing “Swallow Brow” in February.’ On 23 January his entry includes: ‘One morning when little Doline was brushing her hair . . .’.

‘Swallow-Brow: A Fantasy’ appeared in The English Review (I think March issue) and opens: ‘That morning as she brushed her hair little Jo . . . her real name was Mary . . .’

In the early novels of The Flax of Dream Mary (Ogilvie) is based on Doline Rendle, and the journal entry above reflects this – but in The Lone Swallows this essay (see LS, 1922, pp. 182-195) is actually dedicated ‘(To P.T.)’; (‘P.T.’ is not known to me). The story itself is indeed a fantasy – for sad little Jo has a conversation with a swallow which comforts her, and tells her that:

One day, when you are older, someone will come to you, and he will tell you that you are beautiful. He is great friends with the owl, who calls to him at night. But at present he is only a little boy. . . . His name is Willie and he is nine years old.

The swallow gives her a gift – the gift of a swallow-brow (her eyebrows are described like swallows wings).

Interestingly this story contains characters named as Great-uncle Sufford, and an artist named Mr Norman and his daughter Elsie – characters in the The Flax of Dream novels. Indeed, this charming little (rather Victorian) fairy-tale essay is actually what would probably be called today a ‘prequel’ to the The Flax of Dream.

On 7 January 1921 the journal reads: ‘Arthur Beverley Baxter, the Canadian author & literary editor of the Daily Express is friendly towards me’, and on 17 January: ‘Arthur Beverley Baxter is a good fellow. He has taken 3 articles of mine for the Daily Express and paid for them beforehand.’ [That was indeed very kind and generous.] These first articles were headed ‘In the Country’. The first one of these (22 January 1921) is pasted into the RJ Journal (but is not included in LS). The Daily Express printed more than 20 of HW’s articles during 1921, of which eight or nine reappear in The Lone Swallows.

A journal entry under an opening date of 12 March 1921 is long and covers several days. It also covers several diverse subjects, including the entry about the Beresford ‘At Home’. Towards the end of this we find: ‘I am now in Devon. I’ve left London; all my eggs are in my one basket of literature, and I’ve got £12 in the bank. Meanwhile I work.’(Somewhere, I know, I appear to have stated that HW arrived in Devon on 21 March: that was obviously a typing error for ‘12’ – although the former is more romantic!) Two days later (14 March) he wrote:

I do my own cooking in a “double cooker” – God bless the man who invented double cookers. Tonight I stole a lot of pine logs belonging to the Rector; at the moment of writing they are sizzling in my fireplace – an open one. The Rector is a curious fellow; he never visits his parishioners [de rigueur at that time] (they despise his ‘riverence’ – say that he is ‘no gennulmun’) and runs a small commercial lorry for profit. His wife is not pretty; she wears a great fur coat in the warm weather, paints her cheeks and eyelashes, and has an objectionable lap-dog that squeaks at me. It is brown and looks like a cross between a rat and a spider in a potting shed.

This rector appears as Rev. Garside in The Pathway, with whom Willie exchanges opposing opinions.

27 March 1921: Today I am happy for an essay of mine entitled 'Spring in a Devon Village' appeared in The Saturday Review. I met Gerald Barry of the editorial staff during the first night of Mackenzie’s bad play ‘Columbine’. A nice fellow, and a lover of the countryside.

This story is entitled ‘Lady Day in Devon’ in LS (pp. 8-13): Lady Day is 25 March, Feast of the Annunciation. That has always seemed an awkward title, and that it would mean nothing to many readers, especially in the USA, is shown by its new title of ‘March Day’ (Dutton edition, 1926), while in the 1933 illustrated edition it becomes ‘Spring in Devon’.

But on 21 March HW had recorded: ‘I saw a pair of swallows, a solitary pair. They are at least 3 weeks early.’ A week later, 28 March: ‘Today upon Baggy North side I saw a solitary pair of swallows. I will write a paper on the thoughts I had.’ Towards the end of April he wrote:

One of my best things “The Lone Swallows” is with the Saturday Review. I wrote it for ‘Mary Ogilvie’ [Doline Rendle] now at Cambridge and miserable. I’m here and happy. I pursue her no longer, hence miserable letters from her.

(But this story is not dedicated to Doline. As stated, her dedication is attached to ‘Midsummer Night’, written in May 1920 when his romantic feelings for her were blossoming. ‘The Lone Swallows’ essay has no dedication.)

This essay opens: ‘Along the trackless and uncharted airlines from the southern sun they came, a lone pair of swallows . . . The last day of March had just blown with the wind into eternity.’

Note the perfect phrasing of that last sentence. The six and a half pages of this paean of praise of these birds of delight, as ‘Light of heart the wanderer watched and waited’ for more swallows to arrive to add to this uplift of heart and mind, ends on a sombre note:

. . . two dark arrowheads fell with mighty swoop from heaven, arrowheads that did not miss their mark. There was a frail flutter of feathers in the sunshine, a red drop on the ancient sward . . . The peregrine falcons had taken the lone and beloved swallows.

Sudden death was never far from HW’s deepest thoughts, especially at that time still so close to the recent horrors of the First World War and the fear of imminent and undeserved death. This story is surely an allegory, not just of the war, but of the death of his romance with Doline (the little ‘swallow-brow’ maiden).

This is the story (LS, 1922, pp. 1-7), of course, that gives The Lone Swallows its title. It appeared in The Saturday Review May issue: on 8 May HW wrote: ‘Gerald Barry, of The Saturday Review, writes that I will do great things, and that the “Lone Swallows” to be published next week, is a ‘glorious thing’.

The Saturday Review, founded in 1855, was one of the most influential and prestigious journals of the time. Originally political, it had by this time broadened to a more literary slant with contributions from literary lions such as Thomas Hardy, H. G. Wells, Max Beerbohm, and G. B. Shaw (as drama critic).

There follows a long gap in the RJ journal: the next entry is dated April 1922:

Nearly a year has elapsed since my last entry. Much has happened. . . . ‘The Beautiful Years’ got some good reviews (it was published last October) and at Xmas had sold about 750 copies.

‘Dandelion Days’ was finished last September, and is to be published this coming autumn. With Collins I have a nature essay volume called ‘The Lone Swallows’.

One way and another, I don’t think HW could really grumble about a lack of attention or success in these early days!

In the spring of 1922 (the first date mentioned in his RJ Journal is 8 April) HW met Esther Graham Stokes, a very well-to-do lady recently widowed, who with her family had moved to Georgeham. HW immediately fell in love with one of the daughters, Mary, aged 16½, but indicates that the mother was in love with him. This family mainly appear in later books, and I will give them more attention then: but HW dedicated ‘Peregrines in Love’ (To E.G.S.) (LS, 1922, pp. 130-35). This story was first printed in The Field,on 16 July 1921 (yet another prestigious journal). HW comments in the RJ Journal (not dated, but soon after 18 April 1921):

Sir Theodore Cook, Editor of The Field, likes my short paper ‘Peregrines in Love’. But, he writes, it must be submitted to his ‘falconry expert’ before publication.

Well, it obviously passed muster! I have always presumed that ‘E.G.S.’ must be the mother, Esther, but her eldest daughter (who appears later as ‘Queenie’) was also named Esther, while her son (the youngest child), known to be a ‘faithful shadow’ of HW, was Edward (see HWSJ 47, September 2011, Edward Stokes, ‘The Owl Club’, pp. 76-84 for the interesting background) – so ‘E’ actually could also refer to either of them.

Mary Stokes’ dedication is attached to ‘A Seed in Waste Places’ (LS, 1922, pp. 212-16) which is at heart a story about having and losing a dream or a wish (to catch a dandelion seed is supposed to grant your wish will come true).

An interesting point here is the speed with which HW attached their names to these stories – as stated above, the book was already in the hands of the printers when he first met the family. Those dedications have to be proof stage insertions.

‘Winter’s Eve’ (To T.H.H.T.) (LS, 1922, pp. 196-203): – in the 1933 revised edition this is stated clearly as ‘Terence Tetley, in memory’ (see LS, 1933, p. 214). Terence Tetley was one of HW’s greatest boyhood friends. He is part of ‘Jack’ in The Flax of Dream, and appears as Desmond Neville in the Chronicle of Ancient Sunlight series. Terence accompanied young ‘Harry’ on many of his excursions into the countryside bird-watching and egg-collecting. They remained friends but became more distanced during the war, and he fades out altogether afterwards, after a major quarrel.

HW picks out this essay for mention in his ‘Compiler’s Note’ of the first edition, which shows how important it was to him to remember this friendship, even if it had ended sourly. In the 1933 edition there is a footnote within the essay (attached to the fact that barn owls were more common than wood or brown [tawny] owls) which states:

* This was written in the winter of 1914/5 while in Flanders. . . .

(But see also the scan of the ‘blurb’ of the back-flap of the 1933 edition at the bottom of this page.)

That cannot be substantiated, and I feel is very unlikely. In his ‘Notes to the New Edition’ (1933 edition), he states it was written ‘at twenty-one’ (which muddles the dating anyway!) and again there is no corroboration, except that he was 21 on 1 December 1916, and the following year during his long convalescence at Trefusis House in Cornwall (still aged 21!) is when (I am sure) he did begin to write – quite possibly suggested as a therapeutic measure for the breakdown he was obviously suffering. Or perhaps the 1918 ‘after the Armistice’, as stated on the 1933 ‘blurb’, is the true date.

Certainly HW is recalling an episode from his younger days, and although in the story the narrator is on his own, no doubt he and Terence did have similar experiences together. The story is about owls, tawny and barn. But the narrator has once found a dead barn owl, shot. ‘An owl rarely dies immediately.’ That reference to Flanders, attached to barn owls, is possibly likely to have been placed as a metaphor for those comrades he had seen shot to death in the Front line, who also would not have necessarily died immediately: the owl, ‘a beautiful bird [now] a wasted bundle of bones and feathers, flung among the thorns.

‘Ernie’ (LS, 1922, pp. 204-11) is possibly the most Arcadian story in the book. It opens with a straightforward description of Skirr Cottage (in Georgeham, North Devon). Then Ernie enters the story:

A funny little fellow, about two and a half years old, with yellow curls and solemn brown eyes. . . .

Dirty face, wet boots, disturbing voice, everlasting questions, and possessive boastfulness.

Within the short seven pages of this story, about 1500 words only, we know Ernie as a living person. He is a mischievous faun, an innocent Pan living in the imaginary world of childhood: his flute being his incessant voice. Its strength is its simplicity and its truth. It happened just as it reads.

Ernie was the young son of the couple living in the cottage adjoining Skirr – in the little row below the church, set back and separated from the road by a small walled garden in front. Their name in HW’s various writings about Georgeham is ‘Revvy’ Carter (& Mrs Revvy Carter) – real names Mr and Mrs William Gammon.

One of the most powerful stories in the book is ‘Tiger’s Teeth’ (LS, 1922, pp. 96-115), told to HW by ‘Muggy’, one of the great characters of that corner of North Devon where HW went to live in March 1921. The story is dedicated ‘To J.S.’ – that is John Smith, who is Muggy himself. Matthews notes this story as being printed in Wide World Magazine in1922, but there is no mention of this in the RJ Journal.

The tale tells how John Smith and his friend ‘Tiger’ and Tiger’s brother Aaron – blacksmiths by trade, cliff-scalers (for birds’ eggs) by choice – decide that dead lambs are being killed by ‘thay ravens’, a species actually protected by law, and as they can make money by selling raven fledglings to a collector, then decide to raid the nest situated half-way down the cliffs at Baggy Point. (Baggy Point was one of HW’s most favourite haunts. Today there is a plaque at the entrance commemorating this fact.)

The climax of the story tells how, after a perilous descent, Tiger manages to get the fledglings but his holding rope becoming out of action he has with the greatest difficulty to climb back up, and to save himself at the last overlap has to use his own teeth to hold on and haul himself over the last and most dangerous jutting ledge. Safely back at the cottage with some beer inside them, a noise frightens them, and in the ensuing scuffle the fledglings escape. Thus they lose their bounty – but not their pride! This is basically a true story, although the detail of the teeth may possibly be an exaggeration!

‘The Change: A Fantasy of Whitefoot Lane’ (dedicated ‘To J.R.’) (LS, pp. 217-235) is an extra-ordinary story in all senses. A man stands at the edge of a wood (in Whitefoot Lane) and is approached by another. The first man talks of things from the past although he appears a young man, and after describing how the area had been years before, idyllic woodland but now built upon, tells of love lost to him because of his own (idealistic) egotism. The girl had died. He blamed himself.

What was there left? To recreate that love and cruelty, and write out of my sorrow and folly!

(the underlining is editorial)

The figure fades and leaves the second man alone.

Memory ceased. . . . with a vague mournfulness I turned . . . never again would I go back among those poor trees, where in the cruel days of youth’s sweet hopes had been crushed like a wood-anemone under careless and unknowing feet.

Whitefoot Lane was a road that HW often took as a boy on his way from his home in Eastern Road, Lewisham, to his country haunts of Shroffield (The Seven Fields of Shrofften, as they are called in his novels) and Southend, and beyond. The man in the story is called Julien (hence the dedicatory ‘J.R.’): HW certainly actually knew a man of this name – there is the briefest of mentions of him within HW’s personal papers. But there is surely no ‘stranger’ in this story. HW himself stands there and confronts his younger self. All he can do to atone for the past is to write.

Two photographs of Whitefoot Lane (past and present) were printed in HWSJ 31, September 1995 (p. 41), courtesy of stalwart and knowledgeable HWS member (and dear friend) the late Brian Fullagar, in his essay ‘The Lewisham of Henry Williamson’.

*************************

Some mention must be made of the various major editions of this book, for they could cause confusion to the uninitiated (see Matthews’ Henry Williamson: A Bibliography for a full list).

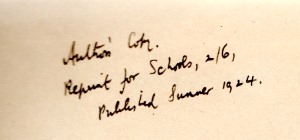

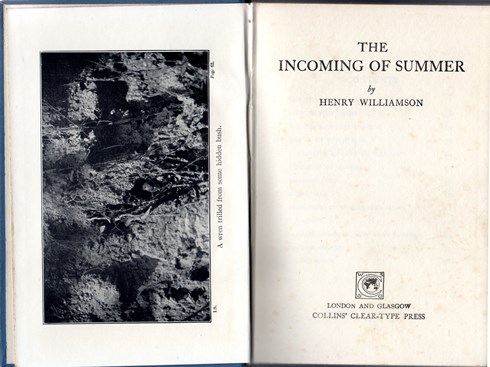

The first change was fairly straightforward: Collins' undated edition (but 1924), in their 'The New World Series', omitted ‘The Outlaw’ (The Lone Swallows, 1922, pp. 116-129), the supposed fake story of the peregrine falcon at St Paul’s Cathedral (it was never reprinted), and ‘The Change’ (but this returned in later editions). HW marks his cutting of ‘Peregrine Falcons in London’, pasted into the RJ Journal, as ‘Fake’, but somewhere he repudiates this ‘false’ story, so one doesn’t know what to believe! Today, when peregrines regularly nest on cathedrals and high-rise buildings, I think we could certainly easily accept it as a ‘true’ story. This small, pocket-sixed edition was intended for use in schools, as HW noted in his own copy of the edition:

Then, also in 1924 (but also undated), the book was divided into two parts, quite straightforwardly, and again for use in schools, the two small volumes being entitled The Incoming of Summer (containing the first thirteen essays) and A Midsummer Night (containing the remaining sixteen). The fact that these three books were printed for school use probably explains why so few copies have survived – today they are extremely scarce and much sought after by collectors.

The Dutton USA 1926 edition (which was the third of HW’s titles to be published by them), was subtitled ‘And Other Stories of the Country Green’, which had previously been used in the UK in 1923 as the subtitle to The Peregrine's Saga. It had a most charming cover, and each story begins with an artistic dropped capital cartouche. The contents are more or less the same as the second Collins edition, and so need no additional annotation.

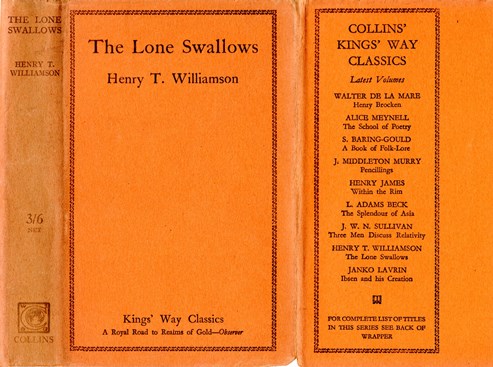

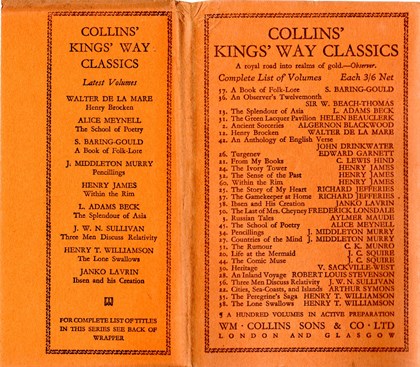

Collins reprinted The Lone Swallows in their pocket 'Kings' Way Classics' series in 1928 (no date is given in the book), which contains two new stories, ‘The Crowstarver’ and ‘Birds in London’, stated to be replacing the earlier dropped ‘The Outlaw’; and reissued it the following year in their 'Collins' Pocket Novels' series.

‘The Crowstarver’ is an important story, more important than perhaps is apparent. It tells of a poor lad earning a few pence by scaring the crows off the farmer’s field. Recent research has shown that it is set in HW’s childhood haunt of Aspley Guise in Bedfordshire, where his mother’s relations (the Turneys and Leavers) lived, and where he used to spend holidays with his cousins Charlie and Marjorie. The crowstarver is based on Jim Holloman, a lad who lived across the road from the Boons, and with whom Charlie and young Harry were friendly. HW used this name for Jim Holliman in The Beautiful Years (who is a cross between Richard Jefferies and HW himself). The story here ends:

For between that vision of green wheat and singing larks and sunshine [of innocent childhood days] lies an immense darkness and corruption, a vast negation of all beauty . . . Its viewless shadow lies over the spinney today, and somewhere in that shadow wanders the ghost of the crowstarver, dead in the war, with that old wraith of myself, in the well-loved places.

Jim Holloman was killed in the First World War (that ‘immense darkness and corruption’), as indeed was HW’s Cousin Charlie. Their names are carved on the Aspley Guise War Memorial. HW has given them immortality in his writing. A group of HWS members recently visited the village and walked round all these old haunts, the house where the family had lived and including the field where Jim had scared off crows and sheltered in the little spinney in the middle. We paid our due homage at the War Memorial.

By the time of the 1933 edition HW’s publishing contracts were becoming complicated. He had left Collins and was with Putnam, run by Constant Huntingdon, who had by then published The Old Stag and the first edition of Tarka the Otter, with a further 1932 edition of the latter illustrated by C. F. Tunnicliffe. (Tunnicliffe’s association as an illustrator of HW’s work properly belongs under the entry for Tarka the Otter.) Huntingdon decided to make a uniform edition of HW’s nature writings, all to be illustrated by Tunnicliffe. This new illustrated edition of The Lone Swallows has 23 full page wood-engravings and 35 vignette chapter head and end line drawings. The order of the stories is totally changed from the previous editions, and are in categories more like chapters.

It was not just a revised reprint however. There are 27 stories from the original book, but some have new titles (for instance, 'The Crowstarver' from the 1928 Kings’ Way Classics edition is retitled 'Boy') and 16 stories from elsewhere, including some from the 1923 Peregrine’s Saga, but also a major new item: ‘A Boy’s Nature Diary’ (The Lone Swallows, 1933, pp. 78-108).

This story is copied, almost exactly word for word, from a prose diary (there is also a separate accompanying ‘factual’ list diary) that HW kept as a lad in 1913 in two school exercise books, recording all his visits to his various ‘preserves’ – privately owned woods and parks for which he had written to the owners and obtained permits of entry – for the purpose of bird watching and egg collecting. This gives the names of his school friends and their occupations and quarrels. It is an extremely important document of HW’s youth. The printed story only covers the first notebook – HW states the rest was lost. Not so! Both books still exist in the archive.

Another major addition to the 1933 edition was ‘The Country of the Rain’, a series of six essays titled by the months from November to April, which had first been published as ‘The Countryside Month by Month’ in New London Magazine, November 1930–April 1931.

The illustrated Putnam edition was reprinted several times in the post Second World War period. A further reprint paperback edition was published by Alan Sutton in 1984.

On the front cover of the Collins 1929 ‘Pocket Novels’ edition is a printed ‘blurb’ which sums the book up very well – even if it was for advertisement:

There is adventure in The Lone Swallows as well as descriptive passages of great beauty; there is life and movement as well as stillness and peace, and its realism will command the attention of the reader from beginning to end. For these twenty-nine pen pictures are not dry-as-dust descriptions of objects of nature, not dull accounts of Nature’s processes, but masterly sketches of Nature as seen through the eyes of a true Nature lover. The writer’s style, almost poetic in its simple beauty, will command interest and arouse a desire to know more of the wonders of Nature.

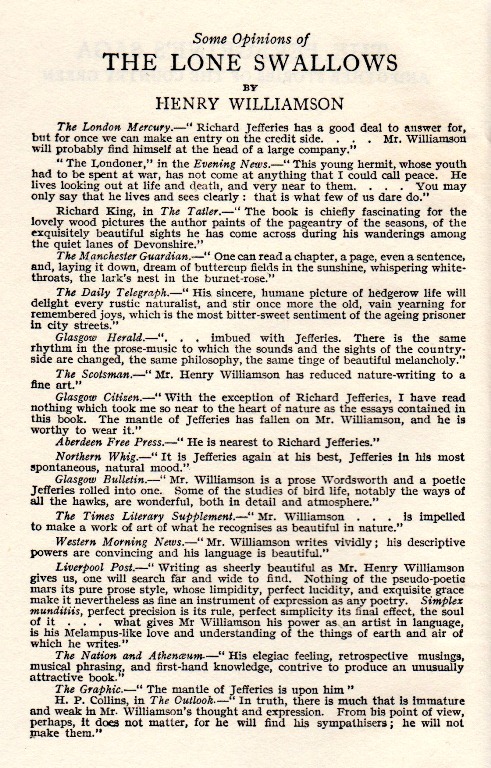

Reviews of the Collins first edition are not in the archive (early cuttings were not kept). Some idea of their content can be discerned from a page printed at the front of The Peregrine’s Saga (1923) which gives quotes (reproduced at the bottom of this page).

There is a goodly selection for Dutton’s 1926 US edition, of which a sprinkling are recorded below. This was the third of HW’s books to be published by Dutton (the first was The Dream of Fair Women, 1924; the second, The Peregrine’s Saga, 1925), so HW was still a ‘new’ author to American readers. Unfortunately the source for these reviews was written in HW’s tiny handwriting in green ink on a dark brown background, and they are now more or less illegible.

A book to satisfy the lover of good writing, as well as those who know and love the woods and fields . . .

Henry Williamson’s “Lone Swallows” will delight the lover of graceful, sensitive, melodious prose with its word pictures of scenes and wild life in Devonshire and will fascinate the nature lover with the poetic descriptions and interpretations of the secrets of Nature. . . .

A collection of essays on nature, with now and then a poignant element of human nature thrown in. Written with a sure hand, colourful, authentic, it is a book that makes for tranquillity of mind. The pure poetry of the prose style gives especial pleasure. . . .

New York Tribune, 5 September 1926, after a long paragraph of praise:

Yet . . . There is not enough variety to give flavour, not enough point to hold the attention. Each sketch might be the prelude to some more important undertaking, a lovely portion, but not a fulfilled whole. One may expect more interesting achievement from the author in the future, for he is a writer of discernment with a limpid and lucid style, and a talent for choosing fine strong words.

St Paul News, Mississippi, at the end of a six-inch column:

It is all very well for a person to be a lover of nature, but such an affection does not always mean that you can make your impressions of interest to another. Mr. Williamson, however, is able to do just that, and the steady flow of words is like a little brook wandering amidst the reeds and rushes . . . nothing lovelier and more dainty could well be written. The volume is a credit to the author and the publishers. (Earlier the writer had praised the jacket: ‘the dainty covering of gray and silver’.)

From an unidentified Omaha newspaper:

A little volume for the nature lover. Observations of a man who goes around with his eyes open to the wonders and beauties of nature. . . . He] just notes and describes quaint habits, queer ways, little things the unknowing might see without noting. Done in prose that is literally poetry, so fine is its touch, so simple its wording. He writes of outdoors in Devonshire, where he has noted the ways of sea fowl and land fowl alike, and has preserved them for the reader, conveying the tenderest and finest reaction of human emotion to the wild life of outdoors.

The number of reprintings and the numerous editions show the importance and popularity of this apparently simple volume.

A page in the preliminaries of the first edition of The Peregrine’s Saga (Collins, 1923) was devoted to extracts of reviews of The Lone Swallows:

*************************

The first edition, Collins, 1922 (there was no dust wrapper):

The front cover and title pages of the three very scarce Collins 'The New World Series' books [1924], printed for use in schools:

The dust wrapper and end papers of the first US edition, Dutton, 1926:

The spine and front of the Collins 'King's Way Classics' edition [1928]:

The dust wrapper of the 'Kings' Way Classics' edition, front and back - note the consistent error: 'Henry T. Williamson':

The spine and front of the Collins 'Pocket Novels' edition [1929], with HW's facsimile signature imprinted on the front:

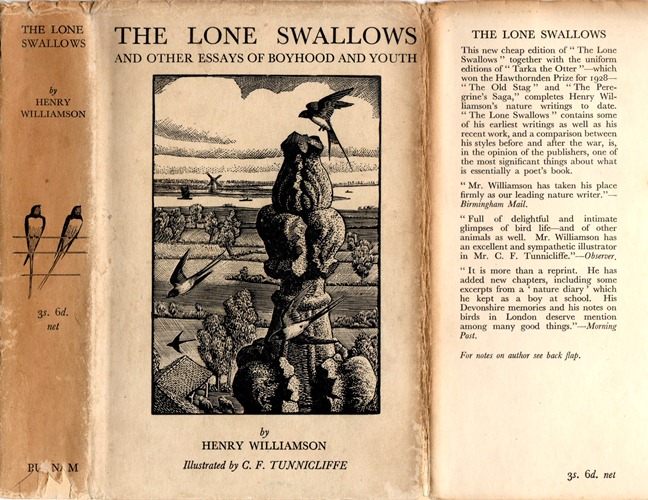

The dust wrapper of the first illustrated (cheap) edition, Putnam, 1933:

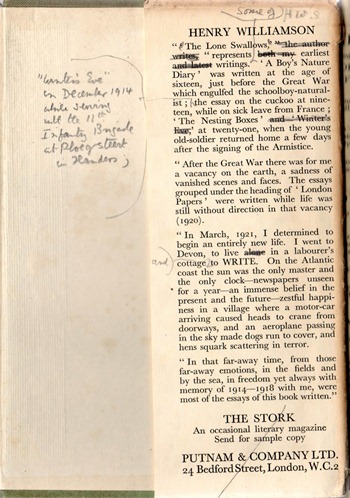

HW's pencilled amendments to the 'notes on author' on the back flap of his own copy:

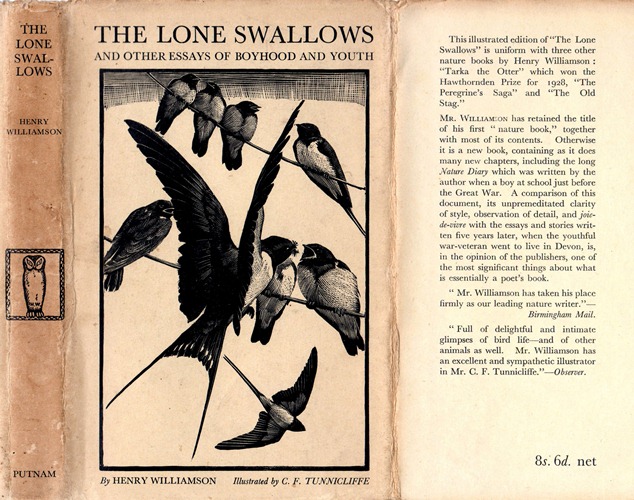

Putnam's 1946 reprint – this superb Tunnicliffe cover illustration of a swallow feeding its young was not included in the text of either the 1933 or 1946 edition:

The Tunnicliffe edition was last reprinted in 1984 by Alan Sutton, using this attractive cover illustration:

Back to 'A Life's Work' Forward to 'The Peregrine's Saga'