FRANCIS THOMPSON

(18 December 1859 – 18 November 1907)

|

|

| Francis Thompson |

A look at Francis Thompson's life and work

The influence of Francis Thompson on HW

Henry Williamson and the Francis Thompson Society

Henry Williamson and Catholicism

'A First Adventure with Francis Thompson' in The Mistress of Vision

'In Darkest England' in The Hound of Heaven

In the mid 1960s HW wrote two major essays concerning the work of the metaphysical and mystic visionary poet Francis Thompson. These two essays were written for, and incorporated into, two separate limited edition commemorative volumes, each containing a single Thompson poem.

1. 'A First Adventure with Francis Thompson'

Published in The Mistress of Vision (St Albert's Press, 1966: 500 numbered copies; 2 guineas)

(St Albert's Press is the imprint of The Aylesford Review, see entry for In the Woods for further information.)

The book did not have a dust wrapper: the binding was of plain mid blue buckram.

HW's essay is reprinted in Indian Summer Notebook (ed. John Gregory, HWS, 2001; e-book 2013).

2. 'In Darkest England'

Published in The Hound of Heaven (The Francis Thompson Society, 1967: 500 numbered copies; 3 guineas)

The book did not have a dust wrapper: the binding was of plain deep blue buckram.

HW's essay is reprinted in Threnos for T. E. Lawrence & Other Writings (ed. John Gregory, HWS, 1994; e-book 2014).

*************************

A look at Francis Thompson's life and work

Before discussing HW's essays it is perhaps helpful to give some background to Francis Thompson's rather complicated life and work; and then to discuss HW's own involvement. It is not really possible to begin to understand Thompson' poetry without some knowledge of his turbulent life and how his poetry evolved; and indeed the extent of it. Further, such knowledge shows why HW would have been particularly attracted to this poet, whose vision of life was very like his own: and so we gain more insight into HW's own writing. The influence of Francis Thompson on HW was far greater than has been previously realised, and I think can be seen as akin to that of Richard Jefferies.

Without first-hand access to Thompson's archive, which is lodged in the USA, for biographical information I have relied on material available within HW's own archive, particularly the two following works, and I acknowledge a debt of gratitude for using their scholarship:

Paul van K. Thomson, Francis Thompson: A Critical Biography (Thomas Nelson, 1961)

John Walsh, Strange Harp, Strange Symphony (W. H. Allen, 1968). This book is enhanced with quotations heading each chapter from P. B. Shelley's poem ‘Alastor’ (as also his title), with which Thompson particularly empathised.)

************

Francis Thompson (hereafter FT) was a great visionary poet, but his poetry is perhaps overshadowed by the world's knowledge of his addiction to opium and his Catholicism. It is necessary to look beyond these 'known facts' to come to an understanding of the man and his gift – his genius, or as he himself called it, his 'daemon'. By this he meant 'supernatural being', or rather 'indwelling spirit', as indeed the true concept of 'genius' is also the tutelary (guardian) spirit of a person. We might say, 'driving force'.

His poetry tends to be considered as being for the 'Catholic' community solely. However, in many ways it can be said that he has been hi-jacked by the Catholic community for their sole appreciation. But FT was Catholic, and if he had not been rescued by a Catholic, then there may never have been any poetry. His poetry is actually of a far broader church – it speaks of the earth and the sky and the universe – and has much to offer in its beauty of expression and thought, whatever one’s religious persuasion. Although some of it is difficult, a great deal is perfectly straightforward.

FT was born in Preston, Lancashire. Immediately there is a complexity, as the date of his birth tends to be given as 16 December 1859, whereas the immediate local record, and FT himself, referred to it as the 18th. His father was a doctor, specialising in homoeopathy, who had converted from a rigid Protestantism to a trenchant Catholicism. His mother, Mary Morton, born in 1822, although not physically robust was obviously strong-willed, for against her parents’ wishes she too had (quite separately) converted to Catholicism in 1854 aged 32. Her parents then disowned her.

She became a novice nun, but quickly discovered she had no true vocation (or rather, it was discovered for her). With no parental support she had to earn her living, and became governess to a family in Manchester. In her earlier years she had been engaged to a young man (whose family had at that time encouraged her religious tendency), but this young man had died (perhaps the reason why she tried to become a nun). Now in Manchester she met Dr Charles Thompson, working in a homoeopathic dispensary.

Their conversion to Catholicism made a strong bond and they were married in 1857. Francis was their second child (the first died at birth). There were also three daughters, of which one died aged two, leaving Mary (b. 1861) and Margaret (b. 1864). It is worth stating here that for a woman not very robust, and marrying at what was then was quite a late age, to bear five children in quick succession was not ideal for Mary's already weakened constitution.

Due to their Catholic faith the family lived a fairly isolated life, and Francis, educated at home, only had his sisters for company. He had a passion for cricket, adventure, and poetry, and read a great deal, particularly the novels of Sir Walter Scott, the poetry of Coleridge and Wordsworth, and Shakespeare – and played with his sister's dolls, one in particular being his favourite.

With no previous experience of school, nor of the companionship of other boys, he was sent at the age of eleven to the College of St Cuthbert, known as Ushaw, a training school for the priesthood, near Durham, where he remained for the next seven years. It was his mother's great wish that he should become a priest in the Roman Catholic faith: no doubt her own failure to become a nun coloured her attitude.

He later wrote of his school years as a time of great unhappiness, relating his experiences as similar to those of Shelley at Eton. However, it is thought that apparently this was not really the case, and his view was due more to his own personality. (One can see a similar tendency in HW.) Certainly the initial shock of finding himself among tough boys must have been quite traumatic.

(Percy Bysshe Shelley, 1792‒1822, was one of FT's heroes, as indeed also of HW. His poem ‘Alastor; or, The Spirit of Solitude’ was FT's guiding light as a young man. The poem is almost the embodiment of 'Romanticism', and relates the search for ideal love: a perfect concept to be found not in 'nature' but in a world beyond.)

While at Ushaw FT read voraciously classic novels and a great deal of poetry (John Donne and similar poets), and also began to write poetry himself. Nevertheless, following the school's training, he intended to enter the priesthood. It is evident, however, that FT actually devoted more time and thought to his poetry writing rather than concentrating on religious contemplation. The Fathers at Ushaw decided that he was unsuited for the priesthood (poetry was almost considered a sin by Catholics at that time – cf. Gerard Manley Hopkins) and in 1877, aged nearly 18, a letter was sent to his father and he was dismissed: to return to the family home in Manchester, feeling himself a failure.

He was then sent to study medicine – his father's profession – at Owen's College, again at his mother's wish. (Two points to note here, perhaps: FT adored his mother and so would not disobey her wishes; he had also, in his training at Ushaw, been taught to obey without question.) But FT was not psychologically suited to the medical profession: he hated the sight of blood and the dissection necessary as a learning tool. (A current suggestion by a spurious source seeking attention that FT was Jack the Ripper is patently absurd.) FT only wanted to create beauty with his poetry and appeared at hardly any of his classes. He kept this fact entirely secret from his parents, who thought him to be attending to his studies.

There is some confusion over his early turn to opium. His mother seems to have been prescribed laudanum for her failing health (possibly tuberculosis – FT's father used laudanum in his homoeopathic work), and when FT was taken ill with a tubercular-type fever in 1879 he may have been given doses of this to relieve his symptoms, quite possibly by his mother. Shortly before her death, she also (rather ironically) gave him to read at this time a copy of De Quincey's Confessions of an Opium Eater, which she had enjoyed greatly. This extraordinary book relating De Quincey's addiction, his penurious flight to London, and his life there with a prostitute, was very well received at the time, but a dangerous influence for the vulnerable – and FT was vulnerable in the extreme. Apart from relieving his own symptoms, the idea of his poetic gift being enhanced by the drug was very attractive.

He quickly became addicted to the drug, meanwhile still supposedly attending medical school, so leading a double life with all its strains. His mother died on 19 December 1880, the day after his twenty-first birthday. FT was totally bereft, exacerbated by his feeling that he had failed her in every way.

The pretence of studying for the medical profession continued, although he equally continued to fail the examinations. The authorities finally reported him to his father in 1884, who removed him and put him to work with a manufacturer of surgical instruments; he was totally insensitive to his son’s unsuitability to such work. This lasted two weeks. He was then sent off to the army – but immediately failed the medical examination. Now aged 25, FT must have felt he was viewed as a total failure.

At the beginning of November 1885 things came to a head. There was a bitter quarrel between FT and his father, and during that night FT left, via Manchester, for London. (Again one sees comparison with HW, who attributed his own flight from London to a quarrel with his father – although in his case that was not strictly true. Indeed, it occurs to me that this thought may have derived perhaps from his understanding of FT.)

In London, FT took on the most menial work in order to exist – boot-blacking, selling newspapers and matches, holding the heads of horses while passengers alighted from cabs – while sleeping rough on the Embankment: a truly miserable existence. This continued until he met a truly good man, John McMaster, who clothed and fed him and gave him lodging, plus a small sum of money for messenger work. Unfortunately, a visit home the following Christmas (where in the strained atmosphere he learned that his father intended to marry again) sent him back into a state of isolation and shock – and addiction.

McMaster finally could no longer cope with him, and FT went back to sleeping on the streets. He was taken pity on by a young prostitute (in a different way, in similar straits as himself). She looked after him, giving him lodging and sharing her own fairly meagre earnings. (Note how all this echoes the life of De Quincey.) In these more secure surroundings he was able to write. He worked up a prose essay, 'Paganism Old and New' (old paganism has no beauty – Christianity has beauty – Christianity gives beauty to New Paganism: beauty being the symbol of a woman's eyes.) He also wrote the rather lovely poem ‘Dream Tryst’.

HW frequently quoted the first verse of this:

The breaths of kissing night and day

Were mingled in the eastern Heaven:

Throbbing with unheard melody

Shook Lyra all its star-chord seven:

When dusk shrunk cold, and light trod shy,

And dawn's grey eyes were troubled grey;

And souls went palely up the sky,

And mine to Lucidé.

(Because of that last word, it is generally thought that this poem was inspired by a meeting with his friend Lucy Keogh during his Christmas visit home. However, more prosaically, could it not be a play on the word 'lucid' itself? Its Latin meaning is 'clear, bright, full of light'. A clear vision out of a drug-induced trance perhaps? FT had to make the word rhyme with 'grey', after all! He was renowned for using archaic words and for making up words.)

At the end of February 1887 FT took his small bundle of work, written on various scraps of paper, and placed them in the mailbox of a small Catholic magazine that he knew of, situated on 43 Essex Street, just off the Strand: the office of Merry England, edited by Wilfrid Meynell.

Wilfrid Meynell (1852‒1948) was then aged 35, a writer and editor, of a Quaker family, but converted to Catholicism when aged 18. Interested in literature, he had gone to London as a very poor young man to earn his living. He had married the intelligent and travelled poet Alice Thompson (apparently no relation to FT) in 1877. Cardinal Manning had invited him to edit the Catholic Weekly Register; then, wanting a more literary outlet, in 1883 Meynell founded and edited the less rigid Merry England, which offered its readers an approach to literature and the arts which was unusually liberal for the Catholicism of the time. The Meynells had several children (not all lived) of which Everard later became closest to FT – while Francis (godson of FT), along with David Garnett, was the founder of the famous Nonesuch Press in 1922.

(In 1964 Nonesuch Cygnet, the junior section of the Nonesuch Press, produced a handsome edition of Tarka the Otter, illustrated by Barry Driscoll. The imprint states: 'Designed by Sir Francis Meynell.')

At this point Wilfrid Meynell, extremely busy with his magazine, merely filed the small bundle of FT's material away for later perusal. FT had given an address for contact but no such contact was made: FT waited in vain – and despair. It is widely 'said' that at this point he tried to commit suicide. However there is no actual evidence of this, other than the hearsay of Wilfrid Blunt, who said he was told this by Wilfrid Meynell; but that may have been a misunderstanding. FT did write about having a vision of the death by arsenic of the despairing and totally penniless poet Thomas Chatterton (1752–1770), at the age of not quite eighteen. Chatterton was lauded by the Romantic poets, especially Wordsworth, who called him 'the marvellous boy'; and Keats, whose poem Endymion was based on him. The story was well-known to FT. The day following Chatterton's horrible suicide a cheque had arrived for his work. FT felt therefore that he should not give up hope – and his squeamishness and his faith (suicide was a mortal sin for Catholics) were certainly against a suicidal tendency. In addition, he still had at this time the support of the unknown prostitute with whom he lived.

About three months after FT had posted his precious MSS, in June 1887 Meynell finally read the chaotic bundle of work, and was impressed. He tried to contact the poet at the given address, Charing Cross Post Office, but FT no longer checked there for his post. It was over a year before FT was to know that his work was considered of value.

To try and flush the poet out Meynell eventually decided to publish FT's poem ‘The Passion of Mary’ in the April 1888 issue of Merry England. FT learned of this through a friend and so he nervously contacted Meynell with a formal note; there was a further wary interval before FT finally approached the Merry England office. His essay 'Paganism New and Old' was published in the June 1888 issue of the magazine.

A dilemma now arose in FT's private life. His association with the kindly prostitute would not be acceptable to 'society'; he was now to be drawn back into the norms of such society. The girl (she has never been named), who must have been of exceptional intelligent awareness, realised this and so removed herself totally from his life and disappeared. FT is known to have searched for her for months to no avail.

After a while Meynell persuaded FT to see a doctor: he was found to be on the verge of total collapse from malnutrition, opium dependency, and the early stages of tuberculosis. He was sent to a private hospital for about six weeks, where he underwent withdrawal from opium addiction, with its attendant unpleasant physical and mental reactions, which he endured stoically.

He then went into lodgings, visiting the Meynell household every day, happily absorbing the literary atmosphere and enjoying the company of two of Meynell's daughters (who reminded him of his own two sisters now lost to him: one had married and went to live in Canada; the other, Mary, had become a nun). FT now flourished, and Wilfrid Meynell realised he had found a superb asset to further the reputation of Merry England. Indeed, an asset that enhanced his own reputation, and which led to his being offered a directorship in the publishing firm of Burns & Oates. This was no one-sided relationship, with FT blandly on the receiving end of Meynell's charity. Everard Meynell makes it quite clear that his father knew exactly what FT was worth then – and would be in the future. His charity was actually an investment.

However, by February 1889 FT had lapsed into opium addiction once more. Meynell now arranged for him to stay at the French-speaking monastery of the Canons of Prémontré, Priory of Our Lady of England, at Storrington, in Sussex. Again FT bore with passive endurance (being a combination of his religious training and his own personality) the mental and physical distress involved in total withdrawal of the drug.

|

| Two views of the Priory of Our Lady of England |

|

|

|

The crucifix in the garden (The above are postcards bought at the Priory) |

Once recovered, he took to walking up the steep track that led to the South Downs, an area known as Kithurst Hill. He wrote here ‘Ode to the Setting Sun’, begun near the large representation of the Crucifixion in the monastery garden and finished on Kithurst Hill. John Walsh in Strange Harp, Strange Symphony, written with access to FT's personal notebooks and letters, notes:

The sun, the most wonderful object of all material creation, gave glory to God by its mere existence, and in its rising and setting symbolized daily the central facts of human life, the Crucifixion and the Resurrection.

FT's feelings about the sun and stars (and nature in general) are very similar to HW's own feelings that he expressed as 'ancient sunlight'. Cosmic imagery features strongly in FT's poetry and prose. The sun is lord of his universe: as it was with Shelley, Jefferies – and HW. (Oddly, although Jefferies' The Story of My Heart was published in 1883, there is no mention of FT having any knowledge of this book.)

‘Ode to the Setting Sun’ was published in Merry England in September 1889. Meynell now sent copies of FT's work to Tennyson and Browning. The latter was particularly enthusiastic, and FT was very gratified, especially as Browning died two months later – with thought, as it were, of FT's poetry in his mind. (cf. HW and Thomas Hardy, regarding Tarka the Otter.)

|

| (Taken from John Walsh, Strange Harp, Strange Symphony) |

In his wanderings on Kithurst Hill FT met some children from the nearby village of Cootham, out gathering wild raspberries that grew up there. He befriended them and was touched by their innocent gaiety. The resultant poignant ‘Daisy’ is among his more well-known poems.

It was also on Kithurst Hill, that September, that he began his famous essay on Shelley. Percy Bysshe Shelley had been born at Field Place, Horsham, Sussex, a few miles north of Storrington and more or less visible from Kithurst Hill. FT would certainly have felt near him in spirit. The essay encompasses a plea for acceptance of poetry (via Shelley) by the Catholic hierarchy:

. . . the worship of beauty is not evil but good. It becomes evil only when it is separated from a sense of the “Primal Beauty”.

Poetry is a manifestation of that primal, essential Beauty. (FT actually saw this Beauty as a 'trinity' consisting of poetry, painting and music. He was treading somewhat dangerously on Catholic rhetoric.) In his essay on Shelley, this spiritual substance, Beauty, is shown as a universal human need. Poetry, as one manifestation of this, is therefore a means of satisfying this innate need. Poetry elevates man above the level of beasts. He addresses the Catholic Church directly:

Poetry is the preacher to men of the earthly as you of the Heavenly Fairness; of that earthly fairness which God has fashioned to His own image and likewise. . . . Eye her not askance if she seldom sings directly of religion: the bird gives glory to God though it sings only of its innocent loves.

FT worked on the Shelley essay until the end of the year. In his 'Notebooks' he states that as it grew under his hand he felt the unmistakeable surge of originality in its mounting level of poetic prose and the audacity of its seething imagery. The essay demonstrates vividly the part played by the uninhibited enthusiasm of childhood in the shaping of the imagination, and shows how these qualities gave rise to Shelley's myth-making power in Prometheus Unbound. (This theme or theory of the 'natural child' is also one that we find in the writings of HW.)

Later, when he had finished the essay, and knowing it would be controversial to Catholic thinking, FT added opening and closing passages to make it more acceptable to readers of the Dublin Review to which it was offered. As he expected, the essay was considered not suitable and rejected. FT did not submit it elsewhere (possibly it was kept by Wilfrid Meynell), and it remained unpublished until after his death – when it was quite happily printed in that same Dublin Review. (And Meynell of course received the fee.)

Meanwhile, out of his thoughts about Shelley FT let his imagination soar into what is considered one of his greatest poems, ‘The Hound of Heaven’, which he began in December 1889. (See the section on The Hound of Heaven for an analysis.) The poem was finished by late February 1890, but with winter set in FT had become bored with the restricted life at Storrington (which surely proves his unsuitability for a religious life). He returned to London in March 1890. ‘The Hound of Heaven’ was published in Merry England, July 1890, and later in Poems (Elkin Matthews & John Lane, 1893).

On his return to London FT moved into lodgings at Queen's Park, Kilburn, and settled down to work and to earn his own living, so he would be independent of the Meynells. The result of this bout of industry was the series of poems (with one long poem) which were gathered in due course into Sister Songs (1895). Much of this was inspired by his association with the young Meynell daughters, Madeleine and Monica, but surely he was also thinking of his own two sisters from that seemingly happy childhood of long ago. It is this work that contains the verse that meant so much to HW, which he wrote out into his copy of The Star-born, and from which he took the title for The Innocent Moon:

Meanwhile, in May 1891 a further son was born to the Meynells. FT was asked to be godfather and the child was named after him: the immediate result was a poem, entitled 'To My Godchild, Francis M.W.M.'.

At this time FT had had no recognition outside the immediate narrow Catholic circle in which he moved. He felt a failure, and his muse seemed to have deserted him. By mid-1892 there was a return to dependency on opium, and in late December 1892 the Meynells arranged for him to be taken into the care of a Franciscan monastery at Pantasaph in North Wales. His state was such that he did not even have any footwear and boots had to be sent to him so that he could take a walk. Father Anselm was in residence and was assigned to keep an eye on him.

The sudden and absolute withdrawal from opium was again difficult, both mentally and physically. But under Fr Anselm's guidance and stimulating mind FT recovered his poetic urge. He was living in a guest cottage, and the proprietor had a daughter, Maggie Brien, who looked after him, and to whom he became attracted. Although uneducated, she gave him warmth and friendship and love (seemingly limited). But it seems that the monastery officials, noting the situation, intervened, and the Briens were quickly moved to another site.

In May 1893 Meynell sent word to say that John Lane publishers had asked for a book of FT's poetry; and so the volume Poems was published in late November 1893. This was well received and went into three editions in the first three months, apparently earning FT £100 in royalties.

While at Pantasaph, FT had contact with Coventry Patmore (1823‒1896; a well-known poet and writer of ideas) and, absorbing much of Patmore's ideas, his own work underwent a change. This intellectual friendship was conducted mainly through correspondence: one is strongly reminded of HW and his friendship with T. E. Lawrence.

The most powerful product of this period was the poem ‘An Anthem of Earth’. It depicts the intellectual and emotional progress of Man from birth to death (the 'Earth' is almost incidental!). It is a secular equivalent of the spiritual ‘Hound of Heaven’, and in it FT uses the Shakespearian blank verse rhythm to great effect.

Meynell now urged publication of Sister Songs on top of the successful Poems, but FT was apparently reluctant, feeling that it wasn't suitable; when it was published by John Lane in June 1895 it was indeed unsuccessful. The critics didn't like it, except for Arnold Bennett who praised it.

FT was now working hard on the material that would comprise New Poems. This would include the extraordinary and mystical poem ‘The Mistress of Vision’. On 8 April 1896 he received a message to say his father was dying. Allowed no money while at Pantasaph (so that he couldn't obtain opium), he had to borrow enough for his fare to Manchester, but his father died on 9 April and he arrived too late. His stepmother refused to see him and he had to take refuge with the local priest, attending the funeral outcast by his stepmother and previous friends. He did visit his sister Mary in her nunnery while there, but returned to Pantasaph very dejected. He sent off the material for New Poems in a depressed mood, convinced his poetic career was over.

Two months later his creative muse returned: 'his work began to sing' once more. FT had returned from Pantasaph to London – and fallen in love. Interestingly (and oddly) the Meynells always kept this very quiet, playing the episode down as if non-existent. Katherine Douglas King – Katie – was a writer herself and at this time a protégé of Wilfrid Meynell, and on 15 June 1896 FT had met her at the Meynells, following which he visited her at her mother's house. In the garden there FT noted that he felt their 'emanations' became as one. (FT had a strong sense of the spirit world and often felt himself in mystical contact with it.)

This intense friendship developed rapidly, but on 26 July Meynell abruptly told a very surprised and puzzled FT that he had to return to Pantasaph. This was possibly due to the intervention of Katie's invalid mother, as she certainly had no intention of allowing her daughter to become involved with FT. However, the two would-be lovers corresponded frequently, and FT now wrote a great deal of verse in the form of sonnets which he sent to Katie: but some are full of apprehension.

In October Mrs King wrote to say that all contact with Katie must cease forthwith, causing FT bitter anguish. Then at the end of November he learned that Coventry Patmore had died. FT had to bear a double burden of grief, and wrote that he felt:

. . . like to one

That standeth alone on an alien beach.

Despite the Meynells’ efforts to hide traces of this love affair, enough remains within FT's archive papers to show that he did not give up Katie quite so easily. In mid-December 1896 he left Pantasaph precipitously, returning to London and contacting Katie, who, after apparently some heart searching, replied in February 1897. He now worked hard at a variety of writing occupations, producing particularly some excellent book reviews and articles, and even one or two lectures. New Poems was published in May 1897, and although many critics failed to appreciate its worth, it fared better than was first apparent. FT gave a copy, together with a photograph of himself, to Katie which she accepted very happily.

Notable at this time was a commission from the Daily Chronicle to write an ode for Queen Victoria's Diamond Jubilee (on 22 June), resulting in Victorian Ode for Jubilee Day, 1897.

In the autumn his health deteriorated with dyspepsia, colds and influenza, all probably exacerbated by a head injury he sustained when run over by a hansom cab. But he continued to work hard with reviews etcetera. The assassination of the Empress of Austria on 10 September 1898 led to his ‘The House of Sorrows’.

Also in September 1898 FT wrote a review of a book by Wilfrid Scawen Blunt (1840-1922; poet, author, diplomat and Arabist). Blunt was a close friend of Wilfrid Meynell and persuaded the latter to bring FT down for a visit to his Sussex mansion, Newbuildings, on 12 October 1898. Blunt noted FT's frailness and reserve. FT absorbed the 'Arabian' atmosphere of the domain, writing An Arab Love-song, which opens with the superb cloud metaphor:

The hunchèd camels of the night

Trouble the bright

And silver waters of the moon

In early 1899 it was evident that something had gone wrong with his relationship with Katie: she disappeared out of his life. Walsh (op. cit., and with access to the FT archive) suggests that FT had proposed to her and she refused, almost certainly due to her mother's influence. Her novel Ursula published soon after contains a passage of proposal and rejection of marriage which would seem to depict and suggest this.

Inevitably FT went downhill again. It is known that by May 1900 he was consuming four or five ounces of laudanum daily. A fourth volume of poetry was rejected by Constable. He learned of Katie's marriage to a Protestant clergyman on 26 June 1900. Driven to despair, FT decided his only course was to go back to life on the streets. He is known to have now written a 'Narrative' of his life (similar to De Quincey's Confessions), but this disappeared and is thought to have been destroyed by Wilfrid Meynell. Violet Meynell was later to refute the statements of both Alice Meynell and the son Everard that FT was happy in his last years as a distortion of the facts, calling it 'benevolent falsification'.

Despite this state of mind and body he was in, FT soon embarked on a very industrious period. Walsh suggests that this was perhaps because he learned that Katie had died on 26 March 1901 giving birth to twins; not because he was callous, but that therefore she was no longer someone else's wife and had been transported to that other world where he hoped to join her. He could put off himself the burden of her apparent defection.

Between 1901 and 1904 FT was writing several reviews a week and a large number of articles, mainly under an assumed name. Interestingly, he kept this from the Meynells, who were totally unaware of the existence of this material, which has only emerged through the industry of scholars in the late 1940s (that is, after the death of Wilfrid Meynell). About 600 items have been recovered. It is obvious that FT was therefore able to look after himself by his own industry – contrary to evidence given by Wilfrid Meynell.

Among the important items from this period is his ‘Ode to Cecil Rhodes’ (who died on 26 March 1902) for the Academy periodical. This led to an invitation from the Daily Chronicle to write an ode on the peace treaty imminent in the Boer War, resulting in ‘Peace’, for which the editor paid him 10 guineas; but then did not actually print it. Thus its first appearance must have been in Wilfrid Meynell's three-volume The Works of Francis Thompson (Burns & Oates, 1913).

Another important poem, ‘The Kingdom of God’, was finished in late 1903, but not published until after his death. It contains the phrase a 'many-splendoured thing', which Han Suyin later chose as the title of her excellent book set in Kashmir; it was later sentimentalised as a popular song. FT’s output then began to slow, illness (now including gout) again becoming dominant – and consequently also his opium intake.

|

|

The frontispiece to The Works of Francis Thompson, vol.3 (Burns & Oates, 1913) |

At the end of 1904 Meynell negotiated a contract for FT to write a biography of St Ignatius Loyola. It was arranged that he would write three pages every day, and take these round to Everard Meynell's bookshop, The Serendipity Shop, for which he would be paid one shilling in order to buy food for that day. This arrangement seemed to work well (although Saint Ignatius Loyola was not published until after his death).

In due course FT’s physical and emotional well-being further deteriorated, and on 19 August 1905 Wilfrid Meynell sent him to the Franciscan monastery at Crawley (Sussex), where Fr Anselm and also Mrs Blackman (both of Pantasaph days) now resided. He was to write an ode for the Dublin Review in honour of the English Catholic Martyrs of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. This was published in April 1906, but without the first 47 lines depicting doom and destruction hanging over the world: these were deleted by Wilfrid Meynell.

By November his energy was failing, but he rallied again with a review of Henry James’s The American Scene in the Athenaeum on 9 March 1907. Father Mann, in charge of his old school, Ushaw, asked for an ode to celebrate the school's centenary for early 1907, but FT was now very frail.

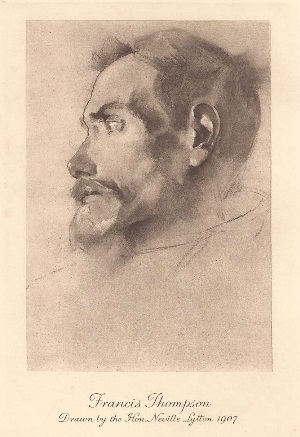

That August Wilfrid Meynell arranged for him to stay with Wilfrid Blunt at his Sussex estate. Everard Meynell accompanied him and stayed a few days while he settled in. FT occupied a bungalow in the grounds. Blunt questioned him about his life and work, and concluded that the vitality of his work stemmed from the tragedy of his life (a simple conclusion, one would have thought!): and that he looked like 'some sixteenth century Spanish Saint' – one is reminded of Don Quixote. Blunt got his son-in-law Neville Lytton to do a portrait: a profile in coloured chalk.

|

|

|

The frontispiece to The Works of Francis Thompson, vol.2 (Burns & Oates, 1913) |

Despite his extreme weakness FT now wrote a review of the works of Sir Thomas Browne, showing that his faculties were clear and precise and his memory unimpaired. But after that he gave up, and was completely reliant upon drugs.

Everard took him back to London on 16 October, and on 2 November he was taken to the Hospital of St John & St Elizabeth in St John's Wood, where he was again abruptly taken off laudanum opium-derivative. Although there seemed to be an initial improvement, such drastic treatment in his weakened state was too much for his frail system, and during the night of 11/12 November there was a relapse. It was realised that he was dying, and the Father on duty hastily administered the last rites.

The Meynells’ son-on-law Caleb Saleeby (husband of Monica) was there, and equally hurriedly wrote out a Will for FT to sign:

I leave absolutely my literary copyrights and papers, including my manuscripts of published and unpublished poems, to Wilfrid Meynell of 4 Granville Place Mews, W.

FT was just able to write his name very shakily underneath. Saleeby and another patient signed as witnesses. FT died at dawn on 13 November 1907 – officially noted as from tuberculosis and related drug dependence. He is buried in Kensal Green Cemetery. His tombstone is inscribed with the last line of the poem he wrote ‘To My Godchild’:

Look for me in the nurseries of Heaven.

(Walsh (op. cit.) states that Wilfrid Meynell orchestrated the obituary notices so they all contained the same information that he had decided upon.)

*************************

After FT's death the Meynells profited greatly from his work. Sales up to the First World War were good, and provided a large income for the Meynells. It is understood that Wilfrid bought his property in Greatham, West Sussex, from the proceeds. Immediate published work consisted of:

Selected Poems (Burns & Oates, 1908, and subsequent printings)

Saint Ignatius Loyola, biography (Burns & Oates, 1909)

Essay on Shelley (first in the Dublin Review, then Burns & Oates, 1909)

The Hound of Heaven (as separate publication, Burns & Oates, 1913)

Works of Francis Thompson, in 3 volumes, ed. Wilfrid Meynell ( Burns & Oates, 1913)

Later Meynell sold the manuscripts (for example, that for ‘The Hound of Heaven’ in 1941 realised £1000).

The biographical writings by Wilfrid Meynell and the full biography by his son Everard of FT were no doubt invaluable at the time of publication, but today they are considered to be, in Violet Meynell's words, 'sanitised'.

Alice Meynell died in 1922. Wilfrid Meynell had a long and established career as a 'Patriarch of English Catholic Letters', dying in December 1948 aged 96. HW met him in 1926 as will be related.

*************************

Go to:

The influence of Francis Thompson on HW

Henry Williamson and the Francis Thompson Society

Henry Williamson and Catholicism

'A First Adventure with Francis Thompson' in The Mistress of Vision

'In Darkest England' in The Hound of Heaven