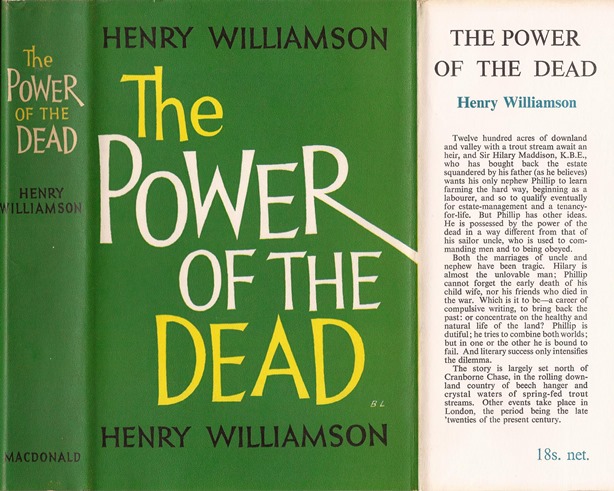

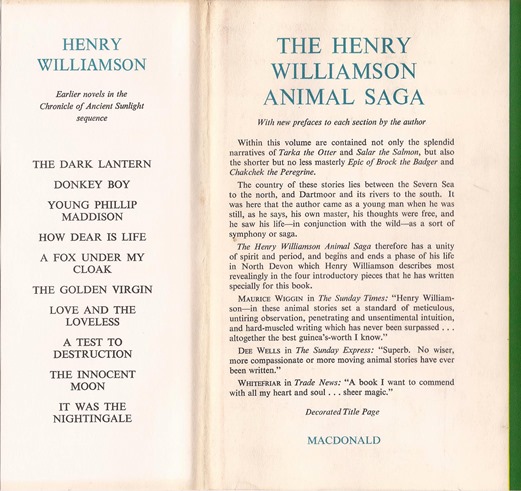

THE POWER OF THE DEAD

(Vol. 11, A Chronicle of Ancient Sunlight)

|

|

| First edition, Macdonald, 1963 | |

'Portrait of an author in North Devon' by Richard Calvert Williamson

First published Macdonald, 11 October 1963 (18/-)

Panther, paperback, 1966

Macdonald, reprint, 1985

Sutton Publishing, paperback, 1999

Currently available at Faber Finds

Epigraph:

Nothing is more corruptible . . . than the artistic imagination living in mere possibilities.

J. P. Stern

Dedication:

To Maurice Wiggin

There is no indication from which particular work by J. P. Stern HW is quoting on the title page. J. Peter Stern (1920-1991) was born in Czechoslovakia of a Catholic-Jewish family and was educated in Prague. He fled to England in August 1939 at the outbreak of the Second World War and was at Cambridge University (where, with various intervals, he proceeded to DLitt in 1975). In 1941 he joined one of the RAF’s Czech squadrons, and was shot down over the Atlantic in 1942, surviving in a dinghy for 14 hours before rescue. Stern was an eminent scholar of German Literature and held many important academic posts (both at Cambridge and London universities) and wrote many works on German authors. An obituary refers to him as ‘one of the most distinguished and influential Germanists of his generation’. His early influences included Leavis and Wittgenstein, reflected in his concern for a literary/historical/social/philosophical blend of criticism.

At the point HW is quoting him (1963) there would appear to have been only two books published: one in 1959 on Lichtenberg (1742-99), an eminent German scientist of his time, the other being Ernst Jünger: A Writer of Our Time (1953), and it is the latter that I would have presumed to be HW’s source. However Dennis Childs (HWSJ 50, September 2014, p. 95) has now tracked the quotation down to an article printed in The Listener, 15 February 1962, entitled ‘Vienna 1900’, from a radio broadcast on BBC Third Programme (presumably that week), which analyses the disparate and contradictory sections of cultural society in Vienna at the end of the nineteenth century (mainly Catholicism and Judaism – both for and against in both cases – and fanatical German nationalism). It sounds as if nothing much had changed by the pre-Second World War period! Childs states that Stern related to ‘the very Viennese belief that only the past can illuminate the present’, which would certainly strike a chord with HW’s own attitude. However, the thought that HW appears to be drawing on here is the torture to the spirit of procrastination of artistic endeavour in need of urgent flowering.

This is an interesting philosophical point that many have made: for instance T. H. Huxley, ‘The scientific imagination always restrains itself within the limits of probability’; and David Hume, ‘Nothing is more dangerous to reason than flights of the imagination’. A favourite saying of HW was ‘He who desires but acts not breeds pestilence’, which carries a similar underlying thought. I think HW’s use of the quotation here indicates the conflict that occurs in his story between Phillip’s dilemma as the practical man of action (farmer) and the man who needed to free his mind and imagination in order to be able to write: a problem which dogged HW himself throughout his writing life.

The dedication to Maurice Wiggin (1912-1986) pays tribute to a man whom HW had known over a considerable length of time, although strangely there is very little mention of him in his archive papers. Maurice Wiggin had a distinguished career as a journalist and was a celebrated columnist for the Sunday Times for many years. His main interests were fishing and motor-racing, reflected in the several books that he wrote. He wrote a perceptive and powerful article about HW, ‘The Hermit of Ox’s Cross’ for the Sunday Times, published on 1 June 1958, which later appeared in his book Faces at the Window (Nelson, 1972); it was reprinted in HWSJ 36, September 2000, pp. 91-4:

Henry Williamson is my most distinguished friend, the only friend I have who is undisputably a genius. I have known him as a writer since the late ’twenties. . . .

But his nature writing is only a fraction of his prodigious output, and to Henry, the less important fraction. He has put his life and soul into the immense novel sequence. It is his message to humanity about humanity that he wants to be remembered by. . . .

Though the best of the nature writing is imperishable, there is a good sporting chance that it is as a Tolstoyan novelist that posterity will praise him . . . The tormented, loving and indefatigable soldier-novelist is a visionary . . . seared to the soul by the years in Flanders . . .

In A Chronicle of Ancient Sunlight he has celebrated his generation, the lost generation; he has placed it in its historical context, most poignantly; he has made his great echoing call for love. . . .

. . . his books will remain. Visionary books, books of a poet with a flame in his heart, a poet who never wrote a verse. Time will sift. The flame will burn more brightly.

*************************

In The Power of the Dead Phillip, newly married for the second time, takes up his Uncle Hilary’s offer to learn how to farm on the family estate at Rookhurst, now owned by Hilary. As the book opens we find Lucy is about three months’ pregnant with her first child. Barley’s son Billy is now a toddler. It is August (although the year is not actually given, by deduction it is 1926), and Phillip is involved with that year’s harvest. We follow his struggles over the next two years as he tries to write and make a name for himself while also learning how to farm. The central theme of the book is the dilemma Phillip finds himself in between the need to learn to be a practical hard-working farmer, and deal with all the problems involved, and its total clash with his main, urgent and only real purpose to become a writer. The shadow of the Great War is ever present.

*************************

HW did not find this an easy book to write. The scenario as above, although it reflects the essence of his life at that time and the problems of his early writing career, does not actually reflect his real life situation. In 1926 HW was living in Vale House in Georgeham and was certainly not a farmer at this stage in his life. Indeed, there was no family farm in the real-life Williamson family. So there are definite shifts of time and place and events which he had to juggle into a comprehensive and believable whole.

An aspect that needs to be considered is why HW brought a farming aspect to the fore at this stage. The plight of agriculture and its importance within society is a dominant feature of HW’s writing from the very beginning. It is a dominant theme in his first book, The Beautiful Years and is a thread in the early part of A Chronicle of Ancient Sunlight. To make Phillip a farmer at this stage serves several purposes and is structurally very clever indeed. First and foremost it highlights the problems and plight of agriculture at this time. It offers a transition between the old ‘Hardy’ method of farming and the more ‘modern’ method that we will find in the Norfolk Farm period. It brings the Maddison family, who are the backbone of the series, back into the forefront. It also covers what in HW’s own life was a fairly quiescent period. He was living in Vale House and writing Tarka the Otter. He didn’t want to just reiterate that, so he had to look outside his immediate life. The scenario he decided upon allows him to expand several ideas at one and the same time.

Part of this farming thread is the reintroduction of the Tofield family, first met in The Dark Lantern where Roland Tofield, heir to a baronetcy, meets Hetty Turney (Phillip’s mother-to-be) in the south of France, to where she has been banished by her father to get her out of the way of Richard Maddison; Tofield asks her to marry him on the strength of a very short acquaintance, but she explains her affections are already engaged elsewhere. Then in chapter six, when (still before marriage) Richard cycles to Rookhurst on his annual holiday and stays with Frank Temperley at Skirr Farm, he learns to his dismay that a rich brewer and ‘city’ man is buying up land in the area, including some of ‘your Father’s’ – his name is Sir Roger Tofield. Sir Roger bought in four of the Maddison farms. Later, when Richard Maddison is in trouble over his job, having married without permission, Hetty secretly contacts her other young beau, Roland Tofield, to ask for his help in getting a job for Richard.

Now it is Sir Roland Tofield who is owner of the land adjoining what is left of the Maddison family estate, and his own son and heir, Piers Tofield, plays a large part in the story from this point on. (There is one small problem: when Hetty meets Piers at the children’s christening she does not react in any way. She should surely have been quite amazed at meeting the son of her former beau. HW does not often slip up.)

That early ‘Tofield’ marker shows that HW had the overall structure of the Chronicle planned from the beginning. Piers Tofield is based on HW’s friend John Heygate; and the character and actions of Piers follow Heygate’s own character and actions fairly closely. Heygate was indeed heir to a baronetcy – but not directly from his own father (who had been a Master at Eton) but from his uncle, who had an estate in Ireland. So the edifice of ‘Sir Roland’, together with this farming scenario, is entirely imaginary.

|

|

|

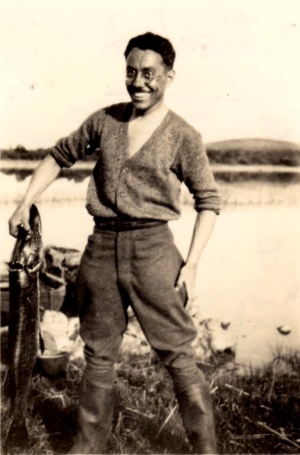

John Heygate from a newspaper dated October 1931 |

|

|

JH at Shallowford at around the same time |

The dominant ‘Uncle Hilary’ is based on HW’s actual Uncle Henry Joseph (his father’s brother), whose role here is totally imaginary. Henry Joseph had been a purser in the Merchant Navy and had a house in Bournemouth (as did Uncle Hilary), but only ever played a peripheral part in HW’s life, although he was godfather to HW’s eldest son, Bill. There is very little information available about him. Henry Joseph died in 1934, aged 62 (and remembered his godson generously in his Will).

|

|

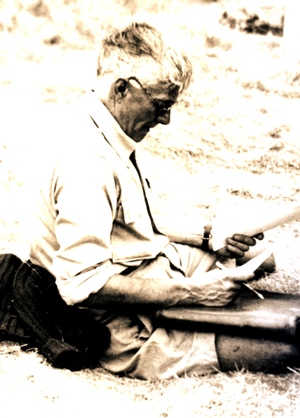

Henry Joseph Williamson 'Uncle Hilary' |

HW’s actual writing problems were exacerbated by the breakdown of his second marriage, as will be shown in the following background. The intensity of his writing load is seen in the following diary entry after a more or less blank period:

2 May 1961: My entries this year have been almost nil because I have been working on an average 75 hours a week for 7 days a week. I have written & revised several times No. 10 novel [It Was The Nightingale] & have started No. 11. No 9, the Moon is due in proof on 15 June.

This current volume is mostly referred to as ‘No. 11’, but here and there as ‘A Drive’ [to Perfection’] – which eventually was dropped as the main title and became the title for Part I of the printed book. (‘A Drive to Perfection’ would have too much echoed the earlier ‘A Test to Destruction’.) By 15 March 1962 the work is well in hand, as he records sending off Chapter 7, ‘A Christening’, to his current typist Elizabeth Tippett in Cornwall, recently separated from her husband and earning her living by typing.

It should be noted that any chapter headings mentioned at this stage do not necessarily appear in the printed version. A great deal of revision occurred before publication.

7 May 1962: I have got out of the habit of moaning to myself in this diary. Reason:- continuous hard work. No 11 slowly builds itself up, with many revisions & refining of original crude scenes. I am now revising, for 4th time, Chapter 9, which brings me to 284-332 typed pages, & only June 1928!! I must, somehow, end at 1937. The scenes become alive after revisions.

The following day he sent off those pages plus ‘beg. of Ch. 10 Grasmere Memorial pp. 333-361’ to Elizabeth Tippett, with various other revised pages from earlier. (As a point of reference, that is chapter 10 ‘Great Day’ in the printed version.)

18 June: Have been writing no. 11 so hard & with perplexity (everything had to be quarried, then ‘endlessly reshaped’) that I am exhausted & prey to many anxieties.

3 July: Not altogether happy days. The revision of Part One of 11 is halting and uncertain. Hilary was too much an Uncle Sally. I must undertake or make him truly human. C. [his wife Christine] not very happy. . . .

The domestic situation was actually very strained. Christine was teaching in nearby Croyde, and in due course admitted to having an affair in 1961 with another married teacher, which was noted by the local populace when she was seen making love next to a large window in the school. She was many years younger than HW of course, who was totally wrapped up in his writing, very stressed, and expecting Christine to run the household. He became increasingly irritable with her (as he saw it) inefficiency. Harry was now at the Exeter Cathedral Choir School and was only at home for holidays.

4 July: . . . At night I took up the much-altered & pawed-over chapter 5 – A Christening. I’d already taken a slice of this for Chapter One, & was apprehensive about how to knit together the tears in the wound. Moderate Hilary! This was done by 1 am & I went to bed softly happy & content.

He had planned a visit to Ireland for 23 July, but now put this off until later as he needed to get on with the writing. He suddenly realised that publication of the Panther edition of Donkey Boy was approaching (due 1 September) and he had not received the proofs. They arrived the next day!

28 July: Panther proofs of Donkey Boy came & I checked the corrections on the Macdonald text. We read and directed morning and evening. My usual misery & impatience. So much to do, such a jumble always. Packed them up at 8 pm & shall post tomorrow.

Sporadic entries during August show his state of mind: ‘Miserable. Frustration by too many things putting off clear-space to write No. 11’. On 24 August he left for two weeks’ holiday with John Heygate at Bellarena, his estate in Ireland, returning on 7 September, the day that volume 10, It Was The Nightingale was published, and immediately started to fret about lack of reviews in the Sunday papers.

22 September: Writing gone wrong. Last few days I had changed Bill Kidd to Piston, & altered much of chapter 10, & also the Bottle Party chapter.

The next day: At night decided to put back Kidd – much relief.

On 26 September he was in London to record at Ealing Studios some T. E. Lawrence material for a BBC TV programme for the following month. On 3 October he finished chapter 10, ‘Piscator’, and sent it off to Elizabeth Tippett. But is dejected by what he sees as ‘failure’ of It Was The Nightingale.

8 October: Wrote a lot of chapter 11 of A Drive – the Martin-Fife-Doodles comedy went well. The question is – & has been for months – where is the novel going? Am I skittering about “all over the shop”.

[Those names refer to Martin Beausire (S. P. B. Mais) and wife ‘Fifi’. The passage does not seem to appear in the published book: the only reference being found at the beginning of Chapter 13 ‘By the Estuary’ – ‘Martin and Fifi had stayed there’ (at Malandine).]

One can see HW’s problems with the structure here, which he does soon resolve to his own satisfaction.

|

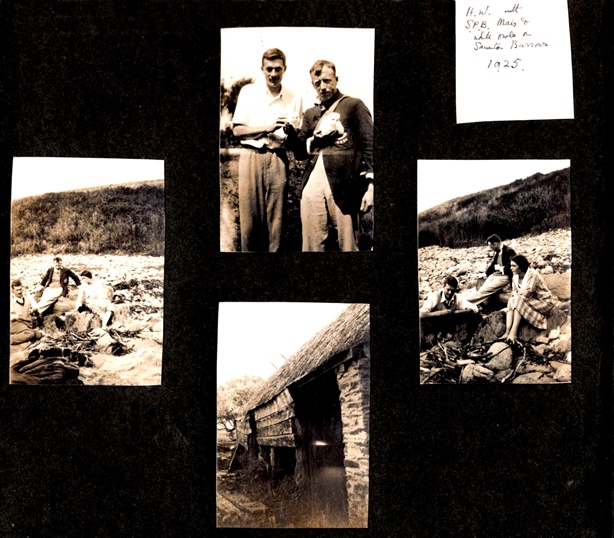

|

A page from HW's photograph album: S. P. B. Mais, HW and Loetitia on the Burrows at Saunton, 1925 In the top centre photograph each is holding a young barn owlet (enlarged below) |

Chapter 11 was posted off to Mrs Tippett on 13 October.

15 October: ‘Now for chapter 12!’

16 October: Suddenly I realised at 8am that No 11 was practically finished: & that to continue after the climax which has been built up from Chapter I - & now coming in chapter 12 (to be written) would be anti-climax; a mere chronicle of one character, or a best another climax to end in 1936. The novel has the usual start, build-up, & end. [And so now it will be No. 12 that will go to 1939] . . . This will relieve this novel of much overweight. Thank goodness I can see clearly after months of worry.

20 October: Worked from 7.45am – 8.15pm on revisions of chapters 10 & 11. Am bringing in CABTON the ‘genius’ before chapter 12 (penultimate) of which I have written about 4000 words. It is all very real satiric knockabout . . .

On 24 October HW noted ‘The awful news of America & Russia over Cuba’. On 25 October he finished recasting chapter 10, ‘A Straw in the Wind’, and 11, ‘Piscator, Venator, Felicis’, and posted them off. Chapter 12 went off on 1 November, and he started on chapter 13. (‘Straws in the Wind’ became the title for Part 3 in the printed version: the chapter title ‘Piscator . . .’ fortunately disappears altogether!)

7 November: . . .doubts about my work. Nightingale has not succeeded. I have broken across my climax of A Drive & every day’s delay makes it recede further.

8 November: Sleepless night. WHAT to do with ‘Felicity’. . . . Felicity must be a ravaged, fatherless girl: who enters the realm of Phillip’s trauma. i.e. she becomes a satellite to his basic neurosis or creative-power-trauma.

12 November: I posted Chapter 13, A Girl Forlorn, pp. 609-643 – pleased with way a delicate situation has been dealt with.

15 November: I finished Chapter 14 – Hunter’s Moon – of A DRIVE TO PERFECTION at 6.15 tonight, in tears. I must record that the story composed itself, quite apart from my prepared synopsis, notes etc. The last two chapters had a minimum of revision because the feeling was threnodie & this is how it was.

On 21 November HW was in London, where he was:

Guest of R.J. Nicholson (child friend of 1918) at Leathersellers Company. Manning of D. Days, the Master. Wonderful evening & atmosphere.

So he was catapulted back into his schooldays. The Leathersellers Guild was patron of Colfe’s Grammar School. Frank Manning was a fellow pupil who had gone on to edit The Colfeian in due course. He had been a private in the RASC and served in France. He features in Dandelion Days. R. J. Nicholson is Roy Nicholson, younger brother of HW’s early love Doris Nicholson (‘Helena Rolls’), with whom HW became very friendly at the latter end of the war, but of whom there has been no mention since that time – evidently he had been in contact.

|

|

HW and the young Roy Nicholson, photograph taken circa 1920 |

HW spent the following weekend at Bungay at the home of his first wife, returning to London and attending his first Sette of Odd Volumes dinner with Alec Waugh (thereby greatly annoying S. P. B. Mais who had asked him on previous occasions and been refused); but by staying late he managed to miss the BBC TV broadcast of the T. E. Lawrence film.

(The Sette of Odd Volumes was – and still is – a private club for book collectors, printers and bibliophiles, the members of which were known as ‘Brother’ plus a suitable pseudonym: HW became ‘Brother Lutra’. One rule was that they had to be amusing – and make a suitable inaugural after-dinner speech.)

On return to Devon on Wednesday 28 November (fairly tired and starting flu, which then kept him in bed for a few days) he was met by Christine with, to his annoyance, John Fursdon, whom he had to entertain. On return home he discovered that Christine had in his absence removed the furniture from his Hut and Studio to their cottage in Ilfracombe, and in so doing had perforce removed papers and books from shelves and drawers; everything was in chaos. He was understandably extremely upset and agitated (particularly about his letters from TEL in which he wanted to check a detail to do with the TV programme just broadcast, and which could not be found for several days), and continued to be so. However he still worked on ‘No. 11’ – revising the last chapter.

On 9 December he drove down to stay with Elizabeth Tippett to finalise No. 11. The work went well. Each time he telephoned Christine she appeared happy and optimistic (as he noted in retrospect), but on 14 December he received a letter from her stating that she had left him and had seen Harry at Exeter and told him this. She stated that she was going to sue for divorce on the grounds of mental cruelty. Totally shocked, HW immediately set off to see (and reassure) Harry. (Various entries in his diary show great concern for Harry’s wellbeing. He was also very concerned that he did not know where Christine was.)

After a couple of days of frantic rushing around he learned from a friend that Christine was actually in love with John Fursdon and would be marrying him as soon as the divorce could be sorted. (Fursdon was the son of HW’s former platoon commander in the London Rifle Brigade from the early days of the war, who had known HW for many years. The Fursdons had property in Devon.) Indeed Christine had already met with the Bishop of Exeter to request to be married in the Cathedral: she received rather a cold reception on several points. Christmas was a chaos of meetings (with solicitors, persuasions, etc.), while he was still working on the final revisions for No. 11, which he left with Mrs Tippett on 27 December and collected again the next day, having been back to Exeter (staying with Dr W. G. Hoskins) and seeing Christine in between.

On the last day of the year he wrote in his diary margin (sideways):

I finished final revision of A DRIVE TO PERFECTION today & posted top copy to Eric Harvey [of Macdonalds] and carbon copy to John Heygate, Bellarena [Northern Ireland].

Heygate returned the TS on 23 January 1963 with ‘admirable criticisms and suggestions where to cut’. HW set to work revising accordingly. On 4 February he heard from Eric Harvey, who didn’t like the title nor its 165,000 word length. On 7 February he had already cut the novel and continued to work all through March revising and cutting. (Researchers should consult and compare the TS copies held at Exeter University.) There is nothing to tell us when he changed the title to The Power of the Dead, but it was obviously during these major revisions.

The next mention is on 6 July: ‘Proofs of The Dead arrived. I got happy into them.’

On 39 July 1963 HW flew to Ireland with daughter Sarah and son Harry to stay with John Heygate. Elisabeth Tippett stayed in the Field while he was away. HW was not happy (but the young people had a wonderful time!) and after seeing Christine on his return on 23 August sank into depression. His diary for 26 August states:

Melancholy. Exhausted. Trying to read coherently page-proofs of The Dead.

27 August: The meeting with C. last Friday disturbing: the winter feelings back in all their weight. No interest in the page-proofs. Has the literary urge collapsed with the will to live.

From 9–14 September he was filming on Exmoor and Dartmoor with John and Ann Irving (BBC), on 18th in the Hut at the Field and on 19th at Exeter Cathedral. From there he left for London, and then on to Italy on 23 September with Ronald and RoseMarie Duncan & their daughter Bryony. Just before leaving he had met Kerstin Lewes (later Hegarty) and fallen for her, and on his return from Italy, on Monday 7 October, immediately sought to see her.

There is no mention in his diary about the publication of The Power of the Dead which, according to Smith’s Trade News notice, was published on 11 October 1963. HW took Kerstin and her sister to the Studio Club on 10 October (which may have been to celebrate publication?) and the next morning, the day of publication, returned to Exeter on the 11 a.m. train from Waterloo, where he saw Harry and gave him presents bought in Italy.

Soon after this Kerstin joined him in Devon. A long note inserted at the front of his 1963 diary, dated 25 October 1963, about Kerstin, includes:

I am in a position, possibly, to be destroyed by my ideal-woman-fixation – revealed in Lily Cornford, Helena Rolls, Barley, Melissa, & a living Galatea at the end of my life. . . .

*************************

At the end of volume 10, It Was The Nightingale, we left Phillip, on his honeymoon after his second marriage to Lucy Copleston, suddenly deciding that instead of going to France and visiting the battlefields they would go back to Skirr Farm at Rookhurst, once owned by Mr Temperley, father of Jack, Willie Maddison’s close friend from the early Flax of Dream series, and begin the process of learning to be a farmer. The farm now belongs to Phillip’s uncle, Hilary Maddison, who has bought it to add to the family estate he also now owns.

The Power of the Dead is divided into three parts: Part One: A DRIVE TO PERFECTION; Part Two: THE SOLITARY SUMMER; Part Three: STRAWS IN THE WIND.

Part One: A DRIVE TO PERFECTION

(As stated this was originally intended to be the overall title of the book. Now the concept is concentrated into this early part of the book’s action.)

'Grief, with a glass that ran -----’

Algernon Charles Swinburne

These words are a chorus from Swinburne’s poem Atalanta in Calydon (1865):

Before the beginning of years

There came the making of man

Time with a gift of tears

Grief with a glass that ran.

Atalanta in Calydon is a verse drama in the style and manner of Greek tragedy. It is an involved mythical tale with a complicated plot about the hero killing a boar which has been sent by one of the gods to plague a king who has annoyed him. The hero, Meleager, has been saved as a baby from a prophecy of death – his life to be only as long as a branch burning in the fire. His mother (the king’s wife) had snatched up the branch and hidden it. At the Hunt the hero falls in love with the talented huntress Atalanta and presents her with the prize for the killing of the boar. His uncles (his mother’s brothers) dispute his right to the prize and so he kills them. His mother, incensed, throws the hidden branch onto the fire – and so Meleager dies.

(The poem contains the well-known words: ‘When the hounds of spring are on winter’s traces.’)

HW is not literally taking on board the whole plot, although one could perhaps pursue some of the ideas and make out a case for them (for example, ‘Before the beginning of years’ can perhaps be seen as ‘ancient sunlight’?). But he is surely concentrating here on the idea of an hourglass filled with the sands of grief (fate?) that are trapped inside their vessel and cannot escape or be escaped. For Phillip Maddison (therefore in essence HW), this inescapable grief is the power of the dead. The dead of the First World War whom he cannot forget, and the more recent tragedy of the death of Barley – the perfect being who casts her shadow over his second marriage and his whole life.

As The Power of the Dead opens it is August (by deduction 1926), and Phillip is working hard on the harvest at the family farm (driving himself to perfection). Lucy, now pregnant, and Uncle John (who still lives in the family home of Fawley House) are taking cold tea and lardy cakes (according to Phillip’s detailed instructions) to the harvest field.

The state, or plight, of farming is established through the conversation between Lucy and John Maddison. The latter is newly invigorated by the presence of the young people. At the harvest field we meet the farm workers: the bailiff, Ned, and Mr Hibbs, the farm manager. It is a set-piece Hardy-esque scene of harvest. But as Phillip works so his mind remembers various scenes from the war, and he thinks about the books he intends to write while his uppermost thought is: ‘Never again, Englishman and German: that would be blasphemy.’

Hilary Maddison arrives in a 2-seater Wolseley. He immediately criticises Phillip’s beard. He has brought a wireless set with a large loudspeaker. Major Crichel, chairman of the local Conservative party appears, canvassing for votes. Phillip, as a socialist, does not like him but Hilary says he has to be polite: part of the job. (HW’s own politics at this time were decidedly of the left: for several years immediately after, and due to the effect of, the First World War, he was a follower of the ideas of Lenin – see The Pathway.)

Hilary is domineering and narrow-minded, but is shown to have had problems in the past, having been devastated to find his father (Captain Maddison) had sold the family farm and deserted his mother, and his own later divorce from the unfaithful Bee.

Phillip finds Hilary trapping young Billy between his legs, just as he had once done to himself when he was a young boy, which drives a further wedge into the relationship. The next morning Hilary fishes on the Longpond. He informs Phillip of his plan for the routine work of the farm and then leaves, planning to return for the shooting later in the year.

Phillip tries to write his book on Barley’s otter, Lutra, but abandons it in favour of his war book. He continues to write all night, and the next day and night, falling asleep at dawn, and is wakened by Billy coming in to say goodnight to the owls calling outside the following evening.

Phillip now learns to plough with the old mule ‘Donk’ (which reminds him of his war experiences) and the old farm plough: all very hard and inefficient work. Uncle John suggests he gets in ‘Johnson’s Iron Horses’ (two traction engines with a 6-plough drawn by cable across the field), as in the past. While waiting for them to arrive Phillip goes up the church tower during ringing practice to write a war scene. (This is actually as in the opening of HW’s important essay ‘I Believe in the Men who Died’, printed in the Daily Express on 17 September 1928, and the subsequent ‘Apologia Pro Vita Mea’ prologue to The Wet Flanders Plain, 1929. See also below.)

The tackle arrives and they work for several days (double deep ploughing – which is later criticised as too deep, as it has brought up a sour under-soil) running up a large bill for which Mr Johnson demands down payment, refusing to finish the job until paid. Phillip has no ready cash and thinks to go over to see ‘Pa’ and the boys to borrow it. But ‘Mister’ tells him the Copleston family is actually in deep financial trouble and are about to be declared bankrupt.

Uncle John pays Phillip’s bill (being partly responsible for it), while Phillip tries to sort out the muddle the Coplestons are in. The brothers resent Phillip’s interference. The situation is worse than thought: everywhere is muddle and chaos and bills are continually coming in. He rushes around trying to raise money and clean up. In desperation he goes to the Clerk to hear what the bankruptcy procedure will be – to hear that all the debts have been paid. Totally mystified, he then learns that Ernest has had a £3000 legacy from his godmother that he has known about all along. (All of this is based on real life.)

Phillip joins a family outing to the pictures to see The Somme, made to commemorate the tenth anniversary of the battle. (This is not to be confused with the 1916 film The Battle of the Somme.) Wikipedia states that this ‘docudrama’ film appeared in September 1927 and was part of a series of similar documentary films on the First World War battles made by British Instructional Films (which became New Era Films) under Geoffrey Barkas and Boyd Cable. Barkas fell ill and the directorship was taken over by M. A. Wetherall, who gets the film ‘credit’.

A large number of local schoolchildren attend the film.

The film began well, with shots of the dumps, new roads, etc., and the preliminary bombardment taken by official photographers in the early summer of 1916. There the marching columns were, waving, smiling, and cheering as exhorted by the camera-men of those sweltering June days. There were the howitzers in their chalk pits, firing in recoil . . . the Leaning Virgin of the basilica of Albert above the horse and lorry traffic of the Ancre valley. . . . But the attack at 7.30 a.m. on Z morning was nothing like it; and spoiled by the incessant shrill cheering of children. There was a moving roll-call scene, when, in pauses of silence while the platoon sergeant looked around, one saw the unanswering names hanging on barbed wire, or lying sprawled upon the pitted downland sward.

But Phillip then sits there in anguish as Germans are portrayed as fat and cowardly, and are loudly booed by the children in the audience, including a moving scene of a German soldier trying to get water for his dying comrade. He thinks of his cousin Willie who had prophesied:

that unless a change of thought came to Europe, and particularly to Britain, the war would come again.

He returns to the farmhouse determined to write his war book. The words Phillip writes here are again recognisable as a continuation of HW’s ‘I Believe in the Men who Died’, first printed in the Daily Express and then as ‘Apologia Pro Vita Mea’ in The Wet Flanders Plain. Very similar thoughts are expressed in his essay ‘Surview and Farewell’ in The Labouring Life (1932), which also involves the symbolic church tower.

Hilary returns in the autumn, and arranges a large shoot with luncheon supplied by caterers. On the second day they are to shoot over the 90-acre still unploughed field for the big drive of the day. All are in place when Johnson’s ‘Iron Horses’ appear to finish off the job abandoned earlier, and noisily cross the field, ruining the drive. Hilary is furious that the shoot has been ruined and that Phillip has hired this machinery on his own initiative and against his farm policy.

Wet autumn weather sets in, so Phillip writes with a clear conscience and gets on with his otter book. Hilary writes to say he can arrange passages to Australia for Fiennes and Tim Copleston – Ernest to stay and look after his elderly father. Phillip goes over to tell them, and asks Tim to accompany him to Dartmoor to get material for the otter book.

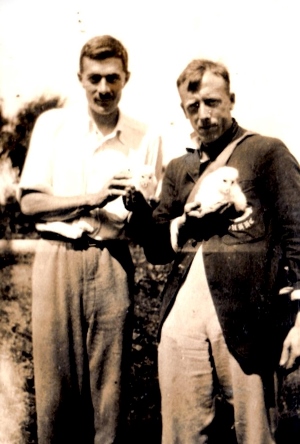

So the two go off to find Cranmere Pool, in drizzle, avoiding the military range gunfire. HW actually visited Cranmere Pool with Robin Hibbert on 30 March 1926, signing the Cranmere Pool visitor’s book:

This scene appears in Chapter 11 of Tarka the Otter, which opens with the very well-known words:

Bogs and hummocks of the Great Kneeset were dimmed and occluded; the hill was higher than the clouds . . .

December brings snow blizzards. Phillip helps rescue buried sheep – a scene reminiscent of a similar occasion in the earlier Flax of Dream series. The snow brings visitors on skis: Piers Tofield and his friend Archie Plugge, who both work for the BBC. This is John Heygate and ‘Bobby’ Roberts, and both did indeed work for the BBC at that time. ‘Bobby’ was also a friend of Evelyn Waugh, the fictional Tony Crufts, whom we will meet directly. They come in for a drink and stay to supper. Over the next few days Piers teaches Phillip to ski.

The new baby, Peter, arrives but Lucy has bad cystitis and the baby doesn’t thrive. Grannie Chychester arranges for her old family nurse, Miss Priddle, to take charge but she is thoroughly unpleasant, upsets everyone and is dirty and inefficient. Finally she accuses Phillip of stealing £10 from her purse and leaves in a huff. (A particular maid did indeed behave like this – but nothing to do with Grannie Hibbert.) Mister’s wife suggests a patent food for the baby which works. That immediate crisis is over.

While buying calves at the local market Phillip sees Piers accompanied by a girl called Gillian. He has a drink with them and then goes back to write his book.

Phillip takes Fiennes and Tim to London (in his Norton sidecar and carrier) on their way to Tilbury and Australia (April 1927). (After the failure of the ‘Works’, the Hibbert brothers did indeed emigrate to Australia around this time.) It is not stated here, but Phillip must also have delivered the typescript of The Water Wanderer to his agent Anders Norse. He goes to see his parents and Richard is eager to hear about his old home.

Part Two: THE SOLITARY SUMMER

Phillip is concentrating on the farm. Ned teaches him how to broadcast seed and he sows the 90-acre field – working out that he will have walked 45 miles in so doing! But there is a drought: the new crop shrivels and fails. Phillip rushes off to write an article for the Crusader (the Daily Express) for July 1, the eleven year anniversary of the Somme, which moves him to tears.

On July the First, eleven years ago, the sun rose up out of the east across the thistly chalk fields of Picardy known to us as Noman’s land. A great battle was imminent.

Continuing over the next half dozen pages, it is an excellent article which, unusually for HW, does not appear to have ever been actually printed, although it is reminiscent of his later article ‘The Somme – just fifty years after’, which was printed in the Daily Express over three days, June 29, 30, and July 1 1966 (so four years after the writing of this present book). (The article is reprinted in Days of Wonder, HWS, 1987; e-book 2013.) HW was writing and placing ‘war’ articles in the Daily Express in July 1927, but they were to do with his return visits to the battlefields (in 1925 and 1927). Entitled ‘And this was Ypres’, and published over 20, 21, 22 and 23 July 1927, they were incorporated into The Wet Flanders Plain. HW was not of course actually present at the Battle of the Somme, although Phillip is, briefly, in the Chronicle, being wounded in the opening assault. HW also wrote an important series of five articles entitled ‘Return to Hell’, printed in the Evening Standard in July 1964 (and incorporated into the 1987 reprint of The Wet Flanders Plain.) Both articles are available on this website.

A christening is arranged for both Billy and baby Peter. Uncle Hilary (to be godfather) arrives with Aunt Dora, having collected her from Lynmouth. He has brought a crate of stout for the nursing mother. Lucy hates it, and Hilary later catches Phillip drinking it. (This is based on a true incident!) He also criticises Phillip’s gardening. Hetty and Irene arrive from London. Also there are Uncle John, Pa and Ernest, and Piers (the other godfather). The next day all go up to Hanger coppice where the men are making hurdles.

Hilary arranges to take Irene to see Barley’s grave at Malandine. They do not offer to take Phillip, who is very upset and walks alone in grief by the Longpond. We learn that Hilary has done much work to improve the water for fishing but much more needs doing. This gives Phillip the idea of writing a book about it.

Anders Norse sends back the typescript of the otter book. The publishers want Phillip to undertake a private edition of 500 copies. Phillip asks Pa about subscription lists for Hunts and he acts accordingly. Meanwhile Norse has found a publisher, Mashie & Co. (a play on the real life ‘Putnam’), offering a better deal. But the new editor wants the hard winter chapter changed. After a frenzy of emotional response, he makes the changes and realises that it is better. (This is all based on real life and the full background can be found within the web page for Tarka the Otter.)

Ernest turns up in a new Crossley car costing £600: Phillip feels aggrieved as the money he put in to try and save boys from bankruptcy has not been repaid. He continues to write hard, rather neglecting the farm work. It is made obvious that the gap between Phillip and his wife is widening: he wants her attention – she is more concerned with domestic affairs.

The prospectus for the private edition arrives, and then in late November the ordinary edition of The Water Wanderer is published to good reviews. Phillip now finishes the book of ex-soldier Donkin, writing the drowning scene with much emotion – opens the window to see the stars and calls out to Willie: ‘Now you can rest’. (Titled here The Phoenix, this is actually The Pathway, published in October 1928.)

In spring 1928 a letter arrives from Miss Corinna Arden (Alice Warrender) informing him that he has been awarded the Grasmere Memorial Prize. (This is, of course, the Hawthornden Prize.) He receives a letter from the famous critic Edward Cornelian (Edward Garnett – HW’s name disguises are usually easily identifiable!).

He goes up to London by train and sees Piers Tofield, who invites him for evening and bed for the night. He goes to see Anders Norse and tells him about the forthcoming prize. Norse says he has been invited to have after-lunch coffee the next day at Romano’s with Cornelian and Thomas Morland (John Galsworthy).

That evening Piers takes him to meet Anthony and Virginia Cruft. (Evelyn Waugh and wife, also Evelyn: they were known as ‘He-Evelyn’ and ‘She-Evelyn’. Waugh’s first book Decline and Fall was published in 1928, and in that same year Waugh married Evelyn Gardner (‘Virginia’), already a divorcee. HW was actually taken to meet Waugh by Bobby Roberts, as recorded in Waugh’s diary. HW is sliding the time-scale here slightly.) Piers then moves on to a nightclub where they see Gillian and another girl, Felicity, a freelance writer working for the BBC. Later Piers phones Virginia, and we realise they have a liaison.

Next day Phillip goes to Romano’s for his appointment.

What writers had once laughed and found happiness in Romano’s! . . . this happy rendezvous of writers . . . Conrad had come from Hythe in Kent to meet H. G. Wells; later with Stephen Crane [whom HW lauds in On Foot in Devon] . . . Ernest Dowson, in hopeless love with ‘Cynara’ [HW’s first choice of record in his Desert Island Discs, broadcast in 1969.] J. M. Synge, remote from his western world’s childhood ever harping in his mind.

His thoughts stir up all sorts of associations, and he thinks about ‘Dear Francis Thompson, companion of the spirit in that swampy summer of 1917 in Flanders . . .’ (His Aunt Mary Leopoldina – the fictional Aunt Dora – had given him a copy of Thompson’s poetry.) He also remembers George Bernard Shaw’s talk at the early ‘Parnassus’ Club (The Tomorrow Club) – ‘Parnassus’ being the home of the Muses, a nice touch.

Phillip is a little nervous about this meeting with these well-known writers. He overhears Cornelian and Morland discussing the ‘Crouchend’ books (The Forsyte Saga) – and how Evelyn Crouchend should die.

(It may be pertinent here to repeat that when I delved into HW’s family tree I discovered that he and John Galsworthy actually shared a forebear – a great-great-great-great-grandfather, a needlemaker in Redditch – totally unknown to either of them. (See HWSJ 32, September 1996, p. 50-55.) It is interesting that these two related (albeit distantly) men should both write a long series of novels about a single family – and indeed, in effect, different branches of the same family.)

The after-lunch coffee ‘interview’ goes well. Cornelian is encouraging about The Phoenix. (My biography, Henry Williamson: Tarka and the Last Romantic, shows how this would all fit into the real-life scenario. Things didn’t happen quite like this – but the overall gist is correct.) Phillip goes back to report to Anders Norse, who show him the work of a new author, A. B. Cabton (the writer H. A. Manhood, a man with whom HW had an uneasy friendship. The background can be found in HWSJ 32, September 1996, p. 47).

From there Phillip goes on to see Piers and Archie Plugge at the BBC. Plugge tells him that he has met Bill Kidd – whom Phillip thought had been killed by the Sinn Fein in 1920. (Remember HW’s notes as he was writing this episode, described earlier: he put Bill Kidd into the tale – took him out – then reinstated him to his own satisfaction. He is based on Bill Child, whose real-life antics were far more outrageous than HW’s fictional portrait!) Phillip later thinks back to the time in the war when Bill Kidd had played a prominent part in his life, causing mayhem with his drunken heroics and refusing to withdraw from the Staenyzer Kabaret during the Germans’ spring offensive in March 1918. He relives the moment when Spectre West and himself were hit by a gas shell:

Everything flaring, fading out as a spray of mustard gas met his face, his eyeballs burning red above a rough remote feeling, followed by infinitely faraway silence while he wondered if his face was blown away and he unable to feel it. The world had vanished, the earth pressing on his face through eyes clenched tight, face ragged in big knots burning in a world on fire.

Phillip returns home, learns that Thomas Morland is to present the Grasmere (John Galsworthy did indeed present the Hawthornden), and sorts out whom he is going to invite to the award ceremony.

He then returns to London to attend, by invitation of Piers, a bottle party given by Channerson, the war-painter, which is described in some detail. (Channerson is the artist C. R. W. Nevinson, to whom HW dedicated The Wet Flanders Plain. See also HWSJ 34, September 1998, with its cover illustration of an etching by Nevinson and p. 94-96, AW, ‘A Group of Soldiers’.) Piers does not turn up. Eventually he sees Archie Plugge, who tells him there is trouble over Virginia. Felicity is there, also Anders Norse, somewhat drunk, who nearly blows the gaff over the award of the Grasmere to Phillip’s acute anxiety. Virginia turns up very distraite, and asks Phillip to get Piers to contact her urgently. However Piers arrives and takes her off. When the two men meet up much later at Piers’ flat, where Plugge has also planted himself uninvited, Piers explains that Virginia has left Tony Cruft. We learn Anthony Cruft has taken himself off to somewhere remote to write a book.

The day of the award ceremony arrives. Phillip and Lucy have been invited to stay the night with the Morlands (as in real life). The ceremony is at the Aeolian Hall, where there are speeches and the presentation. Phillip is very gauche, and has no speech prepared. The evening at the Morlands is very pleasant but formal. They return home to some local excitement.

Part Three: STRAWS IN THE WIND

Life now becomes a little hectic. Many letters arrive. Anders Norse writes to say Cornelian wants him to take on Cabton to live and work on the farm. (Edward Garnett did indeed suggest Manhood should contact HW: Manhood wrote and invited himself in April 1928. They were friends for a while, but the relationship between two such fiery characters inevitably deteriorated.)

|

| The irrepressible H. A. Manhood |

Felicity wants to interview him for an article. Hilary wants to be informed about the fishing. Phillip goes to the Longpond for peace and quiet. He knows he has to make a decision: farm or write. He sees mayfly emerging, and decides to write book about a trout.

A strident Klaxon horn announces the arrival of Bill Kidd and Archie Plugge. Kidd hints for an invitation to stay and fish. Phillip manages to get rid of them to a pub in Colham. Felicity arrives: almost immediately she offers to deal with the pile of correspondence for him. She tells Phillip her story: her father had left home when she was three and her mother had told her he had been killed in the war. At the age of 14 she had been seduced by her mother’s admirer, Fitzwarren. (Felicity is based on Ann (Myfanwy) Thomas – her father is the poet Edward Thomas, killed at Arras in 1917. HW however diverts from the real story in due course.)

Meanwhile Bill Kidd and Archie Plugge are making merry at the local pub. Phillip walks on the Downs thinking out writing ideas, and hears corncrakes and quails; arriving at the pub he can hear Bill Kidd spinning yarns, so creeps away again. Fishing and poaching yarns are rife (a wild echo of the more prosaic poaching scenes to be found in Salar the Salmon, so there is a strange relativity of time and place).

Hilary, waiting to hear about the fishing, reads newspaper reports about Phillip and the Grasmere with increasing irritation (in the manner of reporters, Phillip’s few words said afterwards have been exaggerated). A telegram arrives from Phillip to say the mayfly are rising, and he sets off for Rookhurst.

At dawn the next morning Bill Kidd arrives at the Longpond, disguises his car with reeds, and proceeds to poach nine large trout. Hilary arrives and Haylock rows him out in the boat. They see Kidd, who just has time to hide the catch. (This is very similar to a scene in Salar the Salmon!) Kidd pretends to think this is Sir Roland’s water, for which he has permission! Phillip is out walking with Felicity and Cabton. Hilary is annoyed to find other people there. He tells Phillip he has decided to go in for milk and dairy farming. Men will have to be laid off and cowmen employed instead. Phillip must give up writing. All in a very dictatorial manner.

Phillip finds himself increasingly attracted to Felicity, but worries about Lucy. Cabton is a difficult guest, for he does no work and has a walking-stick gun with which he shoots at everything. Bill Kidd is also a nuisance, but Phillip manages to get them both away to London, where he buys a Peugeot car. He visits Anders Norse to discuss his war book. Norse tells him Virginia has left Anthony Cruft. Phillip drives down to see Martin Beausire at Worthing. (There is an interesting description of Mais’s study, with its various sporting trophies.)

Piers (with Virginia) phones in the middle of the night to tell him that Lucy has given birth to a daughter, Rosamund. It is August 1928. (HW’s daughter Margaret was actually born in April 1930.) Phillip drives home through the night and finds all well. He offers Piers and Virginia the use of Scur Cottage at Speering Folliot – Lady Tofield has refused to meet Virginia. Later there is a phone call from Hilary to say that Uncle John has had an emergency operation, advanced cancer found, and he has died.

Richard (now retired) and Hetty come down for the funeral. Phillip has been left Fawley House and its furniture. He offers the use of the house to his father, who tells him Hilary may be thinking of giving up the farm as he is losing money. Phillip is optimistic: he has been offered £1000 to write a book about a trout. (HW was offered £600 in first instance for his salmon book, in 1933; the final deal was £750, in September 1934 – see Salar the Salmon web page.)

Phillip goes to stay with Piers and Virginia at his cottage. He buys a canvas canoe with a small sail and there are idyllic scenes of the estuary and swimming. Later they cross over the estuary in the canoe to Appledore. At the inn they learn to their horror that this is where Anthony Cruft is staying. Piers and Virginia escape through the window, while Phillip hides. (This hilarious escapade actually happened. HW, John Heygate and She-Evelyn had to leave hurriedly via the window of the pub when they saw Evelyn Waugh approaching.) Phillip hides the canoe and they return by train to Barnstaple. Unnerved, Piers and Virginia leave for Austria and Germany. Phillip returns to Rookhurst.

Phillip now invites his sister Doris and husband Bob Willoughby, and baby son, for a holiday. This couple are still not getting on, so Phillip whisks Bob off down to Devon to sort out the canoe, which needs repairing. As they return across the estuary the tide is against them and the trip is nearly disastrous, but they are rescued by a fishing boat just in time. Bob behaves oddly and Phillip loses his temper. They return to Rookhurst and the Willoughbys soon return to London. (A week later Bob Willoughby walks out and is never seen again; sadly, this rather tragic episode is based on real life.)

Galley proofs of The Phoenix arrive. Cornelian wants to discuss the book and proposes a visit. Phillip feels the farm is running itself according to Hilary’s new ideas (but the local rumour is that Hilary Maddison has already sold land to the military), so Phillip and Lucy decide to go down to Scur Cottage themselves and arrange for Cornelian to stay at the White House on Braunton Marsh. (This actually happened – except of course HW was still living in Vale House anyway.)

|

|

Edward Garnett – at work even when visiting HW in Devon |

Cornelian wants the details at the end of the book changed. He also wants Cabton to stay, so that Lucy has to go and stay with her cousin Mary at Wildernesse, while Cabton stays in the cottage with Phillip. Everything gets a little complicated. Felicity is to arrive, as Cornelian tells Phillip, to see Cabton.

Phillip goes onto the Burrows by himself feeling desolate. He thinks of Barley, then James Elroy Flecker who had died of consumption, then of all the poets who died in the war.

Georgian poetry died on the Somme. The young star-captains – Sorley, Butterfield, Thomas, Ledwidge, Brooke, Owen, Rosenberg, Grenfell – now glowed phosphorescent in the wood of wild willows in the unclaimed areas of Flanders, Artois, and Picardy. Their poetic race was run. Modern verse now surveyed the waste land of Civvy Street; but no urban poet of alley-way and coffee spoon could speak with the authority of the phoenix – which had no real existence. The fleet of stars was burnt out and black.

That is indeed a very desolate passage – but with a little dig at T. S. Eliot’s ‘The Waste Land’! Longing for companionship he spies figures in the distance who turn out to be Martin Beausire, Fiona, and Felicity, who are staying with Mules in the village. They all walk and bathe but Phillip is somewhat distant with Felicity, until she says it wasn’t Cabton she had come to see! Phillip knows he is falling in love with her and rushes off to help fishermen bringing in salmon with seine nets.

Felicity and Lucy get on so well that when they return to Rookhurst Felicity goes with them. They sort out Fawley House for an auction of furniture, supposedly to raise money to cover death duties. It is all rather depressing. At the pub Phillip discovers there is trouble over Bill Kidd’s cheques bouncing. Phillip settles the necessary debt. In return Kidd takes Phillip fishing/poaching, but they get caught and Kidd rushes off, leaving Phillip to wriggle out of the situation.

(HW plays a nice little word game by calling that chapter ‘Incompleat Angler’ (à la Izaak Walton) and the next one ‘Incomplete Girl’.)

Phillip has joined the Barbarian Club (as HW did the Savage Club at this time), and he drives to London to stay there for publication of The Phoenix. He contacts Felicity and they spend the evening together, returning to his club where he celebrates publication of The Phoenix the next day. (The Pathway was published on 28 October 1928.) He escorts her home where he finds her supposed guardian, Fitzwarren, who is decidedly frosty. He buys papers and finds good reviews of The Phoenix. The book is a success – the only adverse comments being in The Ecclesiastical Times, which found it blasphemous and full of communist propaganda.

The next night Phillip goes to the Gaultshire Regimental Dinner at the Connaught Rooms, meeting up with Lord Satchville and old comrades. But –

It was ten years since the Armistice: the war seemed deeper and darker in the imagination than during the actual days of that lost time: the faces of men in uniform, against the smoke and intolerable crash of bombardment: faces around the piano in the ante-room: ever-gay, laughing faces round the table on guest-nights – these phantoms were more real to him than the living: one must, for ever, say goodbye to old comrades, so that one might always see them with young faces, gay and carefree, in those scenes of the vanished world of the Western Front which could only be entered in silence and alone.

So the book comes to its last chapter: ‘All Soul’s Eve’.

The furniture auction at Fawley House is held. Felicity, now officially Phillip’s secretary, is a great help with the organising. He is hoping to use money raised to make very necessary improvements to the house but the sale does not go very well. But his mind is really on ideas for the trout book. Hilary and Irene are there and stay on for the shooting. Irene goes for walk with Phillip to look at the tree nursery. She has not yet answered Hilary’s proposal: he wants to travel and now plans to make a Trust of the family farm. She knows Hilary is very lonely, but she has grave doubts about their life together and really wants to enter the convent near her home at Pau in the Pyrenees. On their return Phillip gives her a copy of The Phoenix, and she goes off to read it. Later they talk and she shows her empathy and understanding. Meanwhile, Hilary has read the one adverse review (brought over by Mister and left in prominent position), and becomes incensed about his nephew. Further conversation with Phillip does not improve the situation.

After supper, Hilary listens to the six o’clock news on his radio. Phillip is hoping to listen to Parsifal on his own ‘little crystal-cum-valve Cosmos set’, but Hilary says he wants to talk to them all. But before he does Billy stumbles down the stairs half asleep clutching one of the pink paper lanterns which he had found at the sale and which Hilary had brought back from the Far East many years before. Hilary is taken aback but then all go outside to light the lotus blossom lanterns on the Longpond for the festival.

‘The Chinese call the Seventh Moon of the Homeless Ghosts. They believe that certain spirits of the departed hang about where they lived while on earth. . . .’

By the shallows of the Longpond the yellow stubs of tapers were lit by Hilary. There was no wind; the faintest of airs in motion carried the floating papers away from the shore. Standing alone, a little apart, Phillip thought of friends now faceless under the dissolving rains of Flanders and Somme. The Chinese Feast of the Homeless Ghosts was inspired by love; Hilary had been inspired to see again his parents, and the faces of his young brothers and sisters with the hopes of nearly half a century before . . .

The lotus was the flower of immortality; the tapers were symbols of light offered in darkness – the homeless spirits helped away from haunting the minds of the living . . .

It is a most moving scene of compassion and reconciliation, a theme which HW goes on to develop fully in the final volume of the Chronicle series, The Gale of the World.

Felicity feels rather out of it all and moves apart. Hilary, very moved by this release of years’ old emotion, feels that he has come to the end of his tether and begs Irene to marry him.

Phillip goes in hoping to hear the end of Parsifal. Irene joins him. Phillip finally makes a decision to give up writing and farm the land. But Irene now warns him that Hilary has decided to sell out to the War Department. He goes down to speak to Hilary who tells him that he should concentrate on being a writer.

Phillip goes out into the moonlight thinking of Barley and the walk they took on their wedding night. He recites the words from Francis Thompson that he had said then:

As the innocent moon, that nothing does but shine,

Moves all the labouring surges of the world . . .

Felicity still down by the Longpond hears him, and they embrace.

*************************

Index to The Power of the Dead

Between 2000 and 2002 Peter Lewis, a longstanding and dedicated member of The Henry Williamson Society, researched and prepared indices of the individual books in the Chronicle of Ancient Sunlight series (the first three volumes being indexed together). Originally typed by hand, copies were given only to a select few. His index to The Power of the Dead is reproduced here in non-searchable PDF format, with his kind permission. It forms a valuable and, indeed, unique resource. The synopsis (with Peter Lewis's delightfully idiosyncratic asides) is not included, as essentially it repeats information already given in the consideration above.

*************************

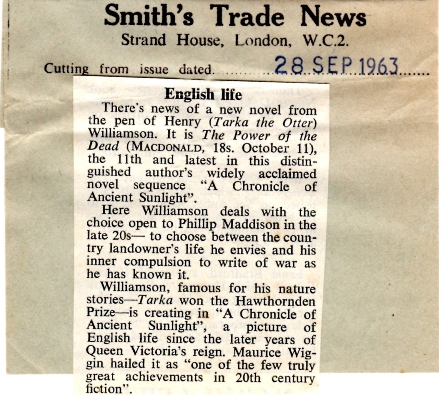

The New Daily, 17 October 1963:

This book is packed with drama and has a certain magnetic intensity which I, for one, found completely absorbing. [Continues with short synopsis of plot.]

The Observer, 20 October 1963:

The eleventh volume of the indefatigable author’s novel sequence in which the hero tries to mend his war-torn spirit with farming and writing.

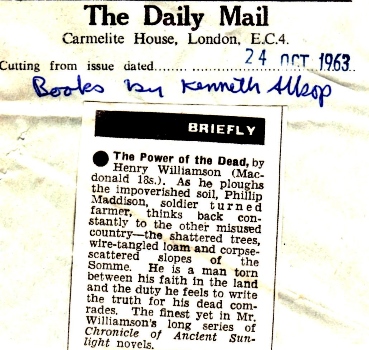

The Daily Mail (Kenneth Allsop), 24 October 1963:

Western Morning News, 25 October 1963:

THE INDELIBLE WAR

Henry Williamson, the North Devon author who has established himself among the leading writers of this century, has extended his “Phillip Maddison saga” to eleven novels.

This has been possible because the works, the literary equivalent of symphonies, are based on themes of the human spirit, with the characters’ reactions sensitively related to enduring previous experience. In The Power of the Dead, the eleventh of the series, the First World War is seen to have left an indelible effect on Maddison which older readers will recall as realistic.

The hero is faced with two rival urges: to continue life in harmony with the ancient land he is farming, or to express his inner and other self as a writer – in effect, to live in reality or in the spirit.

As with all novels the story is secondary in interest to the style. In that , Williamson is poetic. He has a splendid capacity for sounding the harp-like chords of human feeling.

Mid-Devon Advertiser (C.I.S.), 26 October 1963:

A new work from the master’s pen

This is the latest novel by the peerless man among British writers. Little more need be said. Anyone who has grown up with “Tarka the Otter” and “Salar the Salmon” knows the beauty, the integrity, the unrivalled art of Mr. Williamson’s writing. And anyone who has read even on e of the previous ten novels . . . will know that the eleventh should not be missed.

In “The Power of the Dead” Williamson’s hero is in his early thirties, committed in part at least to making a success as a tenant farmer on his Uncle Hilary’s property. But is commitment can only be in part because his heart and spirit still live fully only in his writing.

In this story Phillip achieves the literary success for which he has laboured seven long years. In his farming venture he is less successful, as he is in his second marriage with Lucy. Some of the most moving passages – and there are many – are concerned with Philip’s devotion to Barley, the dead wife of his first marriage.

The story itself is a gripping one. But what a wealth of Williamson’s knowledge, experience and art emerges with each page.

Who else among living British authors could write with such understanding, compassion and equal interest of the state of British agriculture after the first world war, of the London literary scene of the same period, of the wild life of the Wes Country – and of what are now vintage automobiles? No one. And that is quite sufficient reason for reading this novel.

Glasgow Herald, 6 November 1963; (following a review of The President by Miquel Angel Asturias):

There is nothing exotic about Henry Williamson, whose sensitive and expert writing is proverbial . . . The 11 volumes which comprise his “Chronicle of Ancient Sunlight” will surely be essential reading for future literary archaeologists of the First World War and of English country life in the ‘twenties.

The latest addition . . . [Phillip] intolerably bully-ragged by his country-blimp uncle . . . Mr. Williamson “holds the whole war in the palm of this hand” (and who could blame or criticise him for being haunted by its hopeless agony and pulverising battles?) and he writes of country life, fishing, and farming, in meticulous and inexhaustible detail and with great love and understanding.

Liverpool Daily Post (Rosaleen Whateley), 6 November 1963:

Time moves slowly for Mr. Williamson [11th volume and still in the 1920s] . . . Phillip Maddison is divided now between his longing to write and his love of the land. . . . [while] the ghosts of the past walk before his tortured vision. These ghosts are his wartime companions, the men who died in France, the friends he cannot forget. . . .

Daily Herald, 7 November 1963:

The Times Literary Supplement, 1 November 1963:

This novel set north of Cranborne chase in the late 1920s, is leisurely and somewhat verbose. . . . weighted down with not always significant detail, it has something of the compulsive power of the Ancient Mariner – one must perforce read on. The reader marvels at the accurate details . . . [but] . . . the financially cretinous Copleston brothers are unbelievable and too often even major characters are not quickened into life.

New Statesman (Bernard Bergonzi), 1 November 1963; (reviewing 6 titles under overall heading ‘Catholic Herald’ which really refers to Auberon Waugh’s The Path of Dalliance, which gets main attention. Referred to as a ‘right-wing satirist’, the book is compared ‘feebly’ with the elder Waugh’s work’ (i.e. Evelyn Waugh). Also in the list is Colin Wilson, A Man without Shadow – content being ‘man would be a god if he could only enlarge his consciousness, the way to do this is through sex . . . it is time Mr. Wilson grew up out of his starry-eyed attitude to sexual criminals’. John Bratby’s latest novel, Break 50 Kill, is also full of black magic: ‘Phantasmagoria’ seems to be the most accurate term.’ Bergonzi had not read previous volumes of the Chronicle so found Power of the Dead rather confusing:

. . . one can assume that there’s an autobiographical element in the novel. It meanders pleasantly along, rather clogged in places with agricultural or piscatorial detail. The period flavour seems very authentic.

(It is interesting to note that two years later Bergonzi produced Heroes’ Twilight: A Study of the Literature of the Great War (Constable, 1965; Carcanet, 1996) which features, among many others, HW’s war writings. Bergonzi there comments: ‘His narrative resembles an act of total recall by a patient undergoing analysis.’)

Birmingham Post (Geoffrey Bullough), 5 November 1963:

Henry Williamson certainly deserves our respect for the pertinacity with which he plugs away at his vast saga of the Maddison family [the reviewer includes The Flax of Dream in this].

A complex person of varied attainment and experience . . . Mr. Williamson digs into his own detailed memory to produce excellent books in which autobiography and fiction walk together.

He is a fine narrator in the “Georgian” tradition, with a good ear for conversation. . . . describing his hero’s early days as a farmer and as a writer. . . . rural lore here displayed . . . above all that sense of seasonal vitality which the author uniquely communicates.

In deliberate contrast are Phillip’s literary struggles (and thinly disguised literary figures of the ’20s), [all interwoven with] Phillip’s obsession with his memories of the Great War.

Express & Star (Wolverhampton) (Laurence Meynell), 8 November 1963:

Eastern Daily Press (Jennifer Lash), 8 November 1963:

The Guardian (Robert Nye), 15 November 1963:

. . . Phillip Maddison’s soul-searchings have become a bore and his tepid adventures among the trout and the literati get tediouser and tediouser. But perhaps things will brighten up when he goes political with the thirties?

Methodist Recorder (W. Garfield Lickes), 28 November 1963:

Henry Williamson is a writer of distinction. His new book . . . reveals once more the author’s characteristic qualities – intense love of nature, profound and varied knowledge of common things, and leisureliness of narration. Phillip Maddison wants to write. He is haunted by war-time memories and, although married again, is still under the spell of the wife he has lost. His uncle wants him to farm . . .

Phillip, unable to concentrate on either, makes an effort to do both, with an accentuation of the nervous strain that always attends creative work. This conflict is admirably depicted. The story moves slowly, is encumbered with detail – lovers of Williamson and the English scene will read on and ask for more.

A syndicated review by Henry Moore of 3 books appeared in the following newspapers on 29 November 1963 (17 column inches; HW gets 5 inches):

Midland Chronicle & Free Press

Dudley Herald

Tipton Herald

Midland Advertiser & Wednesday Boro’ News

County Advertiser & Herald

For many years Henry Williamson . . . the latest is a fascinating story, which while not reaching tremendous heights is full of vitality. [résumé of plot] . . . The novel has numerous weaknesses but is well worth reading. The author draws his characters well and differentiates them sharply . . . to this is added the warmth of compassion.

Manchester Evening News, 30 November 1963:

Current Literature, December 1963:

Time & Tide, 12 December 1963:

Books and Bookmen, January 1964:

The Daily Telegraph (David Holloway), 3 January 1964:

Sunday Times (Michael Ratcliffe), 5 January 1964:

The Bookseller (Henry Puffmore), 11 January 1964; (pulls the two above together):

Irish Times, 11 January 1964:

Punch (Malcolm Bradbury), 8 January 1964:

Countryman (Ronald Blythe), Spring 1964:

*************************

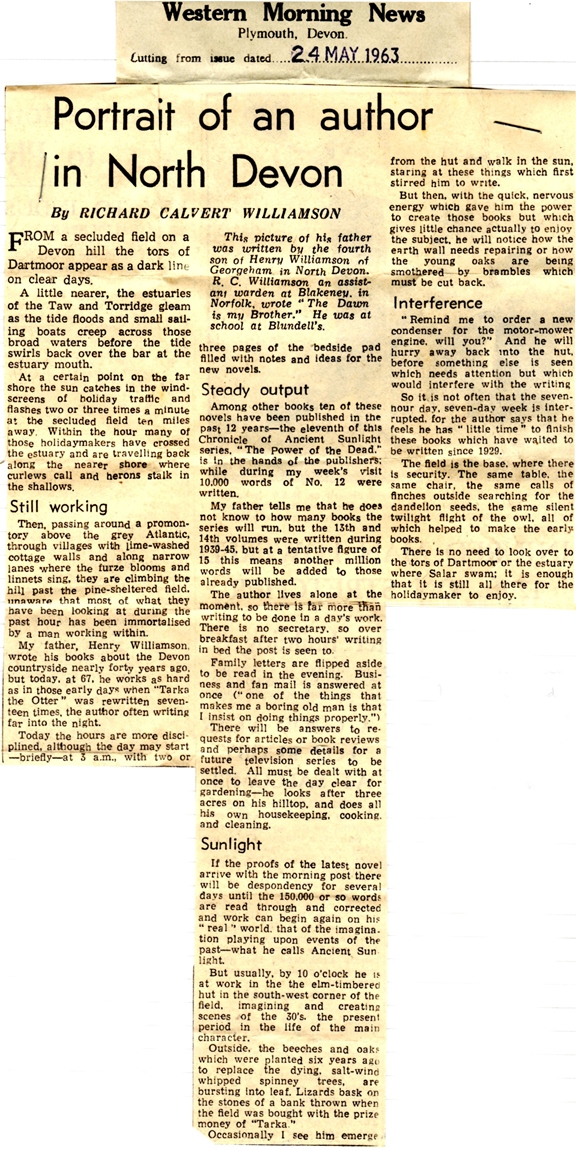

Although not a review, while The Power of the Dead was with the publishers Richard Williamson wrote this feature article on HW, which was published in the Western Morning News on 24 May 1963. The title is an accurate one: Richard paints an excellent picture of HW's routine at this time. He had stayed with HW from Monday, 22 April, to Tuesday, 30 April 1963. HW recorded in his diary on 22 April, 'Richard arrived 3.30 Barnstaple station':

*************************

The dust wrapper of the first edition, Macdonald, 1963, designed by James Broom Lynne:

Other editions:

|

|

|

| Panther, paperback, 1966; and back cover | ||

|

|

|

| Macdonald, hardback, 1985 | Sutton, paperback, 1999 |

Back to 'A Life's Work' Back to 'It was the Nightingale' Forward to 'The Phoenix Generation'